Pink (pronounced pingk)

(1) A definition

of perceived color varying between a light crimson to a pale reddish purple

(sometimes described as fuchsia); any of a group of colors with a reddish hue

that are of low to moderate saturation and can usually reflect or transmit a

large amount of light; a pale reddish tint.

(2) Any

of various Old World plants of the caryophyllaceous genus Dianthus, such as D.

plumarius (garden pink), cultivated for their fragrant flowers including the

clove pink or carnation (sometimes referred to as the pink family); the flower

of such a plant; any of various plants of other genera, such as the moss pink.

(3) The

highest or best form, degree, or example of something (expressed usually as “in

the pink” or “the pink of”).

(4) As

the disparaging slang "pinko", either (1) a communist or one so suspected (US) or

(2) a socialist (UK and English-speaking Commonwealth) (both dated).

(5) In

informal use, a document provided in commerce or by government for some purpose

which was historically issued on pink tissue paper (usually a carbon copy), the

term still in some cases enduring for the modern digital analogue.

(6) In

fox hunting as “the pinks”, a coat worn by riders (although actually in a shade

of scarlet).

(7) In

military tailoring, the pinkish-tan gabardine trousers once worn in some

regiments as part of an officer’s dress uniform.

(8) In

the stone trade, the general term for marble of this color.

(9) In informal

use, of or relating to gay people or gay sexual orientation and used sometimes

as a modifier in this context (pink vote, pink dollar, pink

economy etc (many now dated)). The pink

triangle was a literal description of the fabric patch worn on the uniforms of

homosexual inmates in Nazi concentration camps.

(10) In

labour market demography, as pink collar, that part of the workforce or those

job categories predominately female (dated and now rare because it's assumed by many to be a gay slur).

(11) In

commerce, as a modifier, such products as may be discerned as being of this

color (champagne, gin, salmon, diamonds etc).

(12) To

pierce with a rapier or the like; to stab (based on the idea of a pinkish stain

appearing on the clothing of one so stabbed); figuratively, to wound by irony,

criticism, or ridicule.

(13) In

tailoring, to finish fabric at the edge with a scalloped, notched, or other

pattern, as to prevent fraying or for ornament.

(14) To

punch cloth, leather etc with small holes or figures for purposes of ornament; to

adorn or ornament, especially with scalloped edges or a punched-out pattern

(mostly UK use).

(15) As

pink disease (infantile acrodynia), a condition associated with chronic

exposure to mercury.

(16) In

nautical use, a sailing vessel with a narrow overhanging transom (historically

a vessel with a pink stern).

(17) As

pinky or pinkie, the fifth digit (little finger).

(18) In

gardening, to cut with pinking shears.

(19) In

US slang, an operative of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency (archaic but still used as a literary device of detectives generally).

(20) In

the slang of fishing, various fish according region including the common minnow

and immature Atlantic salmon, the origin of all probably the Middle Dutch pincke.

(21) In

snooker, one of the color balls (colored pink), with a value of 6 points and in

use since the nineteenth century.

(22) In

vulgar slang, sometimes as “pink bits”, the vagina or vulva.

(23) In

slang, an unlettered and uncultured, but relatively prosperous, member of the

middle classes (similar to the Australian CUB (cashed-up bogan)) (UK archaic).

(24) In

informal use, having conjunctivitis (ie pinkeye).

(25) To

turn a topaz or other gemstone pink by the application of heat.

(26) In

(spark ignition) ICEs (internal combustion engines), to

emit a high "pinking" noise, usually as a result of ill-set ignition

timing for the fuel used.

(27) Of

a musical instrument, to emit a very high-pitched, short note.

(28) In

color definition, any of various lake pigments or dyes in yellow, yellowish

green, or brown shades made with plant coloring and a metallic oxide base

(obsolete).

(29) As

pinkwashing (al la greenwashing and the figurative use of whitewashing), a fake

or superficial attempt to address issues of gay rights (though often applied to

LGBTQQIAAOP issues in general).

Circa

1200: From the Old

English pungde (to pierce, puncture,

stab with a pointed weapon) which by the early fourteenth century had acquired

the sense of "make holes in; spur a horse" the source uncertain but

perhaps from a nasalized form of the Romanic stem that also yielded French piquer (to prick, pierce) and the Spanish

picar or else from the Old English pyngan (to prick) and directly from its

source, the Latin pungere (to prick,

pierce), from a suffixed form of primitive Indo-European root peug or peuk- (to prick). By circa

1500, it had come to mean "to decorate (a garment, leather) by making

small holes in a regular pattern at the edge or elsewhere" and that sense

endures to this day in pinking shears (although they were not so-named until

1934). The English pinge, pingen, pinken, pung & pungen (to push (a door)), batter, shove; prick, stab, pierce;

punch holes in) was from the Old English pyngan

(to prick) and dates from 1275–1325 and may be from (1) the Latin pungere (to prick, pierce), (2) the Low

German pinken (hit; to peck) & Pinke (big needle) or (3) the Dutch pingelen (to do fine needlework), the

root again the primitive Indo-European peug

(to prick). Pink is a noun, verb & adjective, pinker, pinkest, pinkish and pinky are adjectives and pinkness is a noun

Lustre-Creme

shampoo “Pink is for Girls” advertising posters, 1960s.

Lustre-Crème was emphatic “pink is just for

girls” which was at the time hardly controversial for most although

the claim they produced the “only pink shampoo” might have been ambitious. It might also have seemed a bit adventurous to

suggest there exists a “pink fragrance” but there may be synesthetes who have experiences of smell associated with color and it’s not unknown to have

the sense of the senses shifted (in opera it’s common to speak of a soprano’s

voice “darkening” as she matures) and

Lustre-Crème did note that “…should a certain someone get too close, he'll notice that

we have a delightful ‘pink’ fragrance too.” Covering the market, for the practical young

lady mention was made of the “…unbreakable plastic squeeze bottle with the new Flip 'n

Tip Spout (no more cap-twisting).” A "Flip 'n Tip Spout" is one of those small innovations which made life more civilized.

The "pink is just for girls" equation is however of recent origin. In

the West, until the late nineteenth century, infants tended universally to be

dressed in white because doing the laundry was a more tiresome (and certainly

labor-intensive) task than today, thus the attraction of white fabric which

could be bleached. Until the early

twentieth century, pink tended to be thought a “strong, masculine” color, (apparently

on the basis of being a variant of red) while blue was seen as more delicate

and so suitable for girls; as well as being considered “dainty”, blue had a

strong historic association with the Virgin Mary because of the manner in which

she’d been depicted by generations of artists.

As late as 1927, department stores like Marshall Field routinely would suggest

pink for boys but within a decade the shift clearly had begun because by the

late 1930s the Nazis had (eventually) settled on pink as the color of the

identifying triangle worn by prisoners incarcerated under Paragraph 175 of the

German penal code (which criminalized homosexual activity between men). It was in the US in the post-war era of

plenty that the “blue for boys, pink for girls” thing was established and it was

a product of marketing, the attraction being that with a clear gender divide,

parents would have to buy more clothes.

From there, the idea infected just about every industry, even tool

manufacturers producing lines of pink tool kits for men dutifull to buy as gifts for Wags (wives & girlfriends).

Speak (2004) by Lindsay Lohan, pink vinyl edition, 2000 of which were in 2020 pressed for Urban Outfitters.

The

words "pinkie" & “pinky” were from the Dutch pinkje, a diminutive of pink (little finger) and of uncertain origin, the

earliest known used in Scotland in 1808 and common in Scottish English, US English

and elsewhere in the English-speaking world.

The nautical use dates from circa 1450, from the late Middle English pynck & pyncke, from the Middle Dutch pinke

(fishing boat). The flows were so

named in the sixteenth century and surprisingly, the use to describe the color

didn’t emerge until the eighteenth century, perhaps as a shortening of "pinkeye". The

flower family was so named in the 1570s, the common name of Dianthus, a garden

plant actually of various colors. The

family picked up the name “pink” probably because of the idea of the "perforated"

(scalloped) petals (ie “pinked” in the earlier sense) although etymologists did

suggest there might be a link to the Dutch pink

(small, narrow (in the sense of pinkie)), via the term pinck oogen (half-closed eyes (literally "small eyes), borrowed

in the 1570s, the speculative link being the Dianthus sometimes has small

dots resembling eyes. The coincidence in

the dates is interesting but there’s no documentary evidence. It was the example of the flower which, by

the 1590s, led to the figurative use of "pink" for "the flower" or highest type

or example of excellence of anything.

Cadillac “targeted”

advertising, gowns for mother and daughter by Jane Derby of New York, 1959 Cadillac Series

62 Convertible, body by Fisher. While long, the 1959 Cadillacs weren't quite this long.

1959 Cadillac Series 62 Convertible in non-original pink.

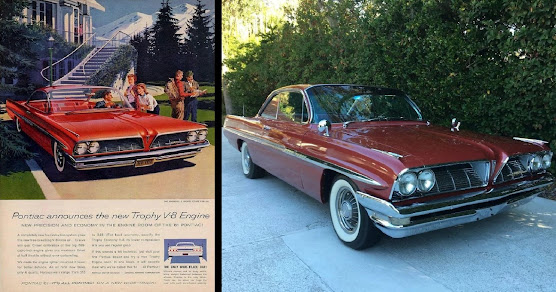

This (unedited) photograph may be compared with the crafted image (above) as an example of the way advertising agencies often preferred simulacrum to reality, some of the representations in the era having a similar relationship to the physical as promotional photographs of hamburgers have to what's really delivered to customers. With the US cars of the era, the finest practitioners of the era were Art Fitzpatrick (1919–2015) & Van Kaufman (1918-1995) whose best known work was the collection of memorable images for General Motors' (GM) Pontiac Motor Division (PMD) during the 1960s. What the chains do to advertise hamburgers blatantly (though not legally) is deceptive & misleading but the exaggerations in the graphical art used for the cars was less so because the distortions were so obvious and they were more in the tradition of mannerism, Fitzpatrick & Kaufman never quite becoming surrealists.

The ex-Elvis Presley 1955 Cadillac, now on display at Graceland, Memphis, Tennessee. Although "peak

dagmar" was achieved in 1955, even then the tail-fins had barely grown from those first seen on the 1949 range.

By 1959 Cadillac's advertising

had for years emphasized the power and speed of their cars or intricacies such

as air suspension or finned brakes. This

was aimed at the men who would be impressed by such things but the company also

had advertisements for women, assuring them “…one of the special delights which ladies find in Cadillac

ownership is the pleasure of being a passenger” before going on to

invite them “…to

visit your dealer soon – with the man of the house – and spend a hour in the

passenger seat of a 1959 Cadillac.”

All that probably did still accurately reflect US society in 1959 (at

least that sub-set which bought cars from Cadillac dealers) but it was in

one way misleading. Although Jane Derby’s

(1895–1965) New York fashion house surely made many pink gowns, no pink Cadillac

left the factory in 1959. There are now many,

many pink 1959 Cadillacs, the model regarded as having the most extravagant

fins available during Detroit's crazy macropterous era, the effect heightened

by the equally memorable "twin bullet" tail-lamps (although the fins on

the 1961 Imperial were just under an inch (25 mm) more vertiginous) but it was

only in 1956 Cadillac had a pink hue on the option chart (as "Mountain Laurel" (code DAL-70663-DQE)).

It was in that color the popular singer Elvis Presley (1935-1977) gifted his mother a car and the use of the phrase "pink Cadillac" in popular culture (song & film) made it a thing although Mrs Presley got a 1955 Fleetwood Sixty Special (a four door sedan) which was originally blue with a black roof.

The roof was later re-sprayed white (the sun is harsh south of the Mason-Dixon Line although the car was factory-fitted with air-conditioning) but people adopting the "Pink Cadillac" motif

usually go monochromatic and pastels ("baby pink" the best known) seem more popular than "hot pink".

Elvis Presley's pink "Guitar Car", pictured with creator Jay Ohrberg (b 1943) (left) and with model in a period promotional photograph (right).

Jay Ohrberg over the decades fabricated literally of dozens of the well-known cars

used for film and television productions but one like no other was the pink “Guitar

Car”, built as a promotional tool for Elvis Presley. Some 41 feet (12.5 metres) in length, it was

based on a 1970 Cadillac Eldorado, improbably a FWD (front-wheel-drive) machine

running a 500 cubic inch (8.2 litre) V8 rated that year at a muscle car-like

400 hp. It was the FWD configuration which

made possible the Guitar Car's unique design, the only mechanical components running within

the “fretted neck” (a tubular steel structure) things like control lines for

the steering, brakes, transmission and such; the engineering for those would

have been challenging enough. While the front end was recognizably still a 1970 Eldorado, the rear section (connected by the fretboard) featured bespoke coachwork including a pair of tail-fins (complete with the “twin bullet” taillights made famous on the fins of the 1959 Cadillac) on a scale which might be expected on an aircraft or machine built to contest the world land-speed record (LSR) with the driver sitting under a tinted Perspex dome, mounted atop the “soundhole”.

The Guitar

Car as advertised on eBay, April 2025. A restoration will be required but 1970s Eldorados are not hard to find and the bespoke bodywork is fibreglass so there will be no rust. The challenge will be fabricating the custom parts such as the canopy, fretboard and tuning keys.

Note the Guitar

Car’s registration plate (just behind the model's knees). While

registering such a machine for use on public roads might seem unlikely, there

was a time when in certain places in the US, such things were possible, Porsche in

1974 modifying a 917 race car (chassis 917-30 which qualified third in the 1971 Austrian

1000 km endurance event) to make it possible to be registered for the road by

an appropriately accommodating organ of the state. In the state of Alabama (in circumstances

still not wholly understood), Count Teofilo “Theo” Guiscardo Rossi di

Montelera, Prince of Premuda (1902–1991) found such an institution and, unlike

the humourless Germans or the French who demanded it first be subject to a crash-test,

all the authorities in Alabama stipulated was the 917 never appear on the state’s

roads. Having little business to conduct

in Alabama, the count agreed, paid however much he paid and duly received

his plate & papers. Count Rossi's connection with the Porsche factory was by virtue of his family's Martini e Rossi distillery firm which sponsored the Martini & Rossi motor racing team running Porsche 917s during the early 1970s but negotiations in Alabama presumably were conducted in the traditional way and Mr

Presley’s people must have found equally helpful staff at the Las Vegas DMV (Department

of Motor Vehicles).

Porsche

917-30 in France, now (somehow) on UK registration 959 DAK.

What the

precious Alabama papers at the time permitted was use on European roads, although

for all sorts of reasons it wouldn’t have been possible to obtain registration

in most of Western Europe, even with one’s lawyer threading clauses through

loopholes. The 917 was later registered

in Texas, another place where things are done which never would be contemplated

in California, Massachusetts or other “blue” (ie Democrat) states and

currently it exists in France on UK registration 959 DAK. There is also a road-registered 917 (917-037) in Monaco, another jurisdiction where the rich find not

only the taxation authorities friendly and before being re-converted to race-specification, 917-012 (not 917-021 as is sometimes reported) was, briefly, road-registered. A

few days before the Guitar Car was advertised, 917-30 showed up in a

teaser video from Porsche dropping the hint the factory might soon release a road-legal

version of one of its current racing cars (probably the 963 prototype) and an announcement

is promised for June, presumably to coincide with the 2025 24 Hours of Le Mans. Whatever is released will doubtless be a fine machine but what won't change is the 917 will remain the greatest Porsche ever.

Count Rossi

with Porsche 917-30 Strasse (Street) on Alabama registration 61-277 37 (1975).

Count

Rossi did sometimes take 917-30 on the roads of Germany & France and Mr Presley

really did drive the Guitar Car to a show at (of course) Las Vegas but after

that it mostly vanished from public view apart from a sighting in the Middle

East until, in April, 2025, in a dilapidated condition, it was advertised for

sale in France. The asking price was listed as €10,000 (US$11,500)

and quite what value that represents will be in the eye of the beholder

because, being unique, there’s little with which it can be compared. Overseas buyers should note the largest

standard shipping container has an external length of 40 feet (12.2 metres)

with the internal dimension slightly less so some disassembly (and subsequent

reassembly) might be required and a warehouse or aircraft hanger will provide a

more appropriate storage space than most garages.

Pink Pig Porsche 917-20, 1971.

Although it raced only once, the “Pink Pig” (917-20) remains one of the best remembered 917s. In the never-ending quest to find the optimal compromise between the down-force needed to adhere to the road and a low-drag profile to increase speed, a collaboration between Porsche and France's Société d’Etudes et de Réalisations Automobiles (SERA, the Society for the Study of Automotive Achievement) was formed to explore a design combine the slipperiness of the 917-LH with the stability of the 917-K. Porsche actually had their internal styling staff work on the concept at the same time, the project being something of a Franco-German contest. The German work produced something streamlined & futuristic with fully enclosed wheels and a split rear wing but despite the promise, the French design was preferred. The reasons for this have never been clarified but there may have been concerns the in-house effort was too radical a departure from what had been homologated on the basis of an earlier inspection and that getting such a different shape through scrutineering, claiming it still an “evolution” of the original 917, might have been a stretch. No such problems confronted the French design; SERA's Monsieur Charles Deutsch (1911-1980) was Le Mans race director. On the day, the SERA 917 passed inspection without comment.

Der Trüffeljäger von Zuffenhausen (The Trufflehunter from Zuffenhausen), a fibreglass display (some 45 inches (1150 mm) in length) finished in the Pink Pig’s livery. It includes battery-operated LED (light emitting diode) fixtures within the nostrils, activated by a toggle switch under an access panel on the neck. Weighing some 50 lb (23 kg), it measures (length x width x height) 45 inches x 20 x 32 (1140 x 510 x 810 mm). In an on-line auction in 2024, it sold for US$3800.

Pink Pig Porsche 917-20, Le Mans, 1971.

At 87 vs 78 inches (2200 mm vs 2000 mm), the SERA car was much wider than a standard 917K, the additional width shaped to minimize air flow disruption across the wheel openings. The nose was shorter, as was the tail which used a deeper concave than the “fin” tail the factory had added in 1971. Whatever the aerodynamic gains, compared to the lean, purposeful 917-K, it looked fat, stubby and vaguely porcine; back in Stuttgart, the Germans, never happy about losing to the French, dubbed it Das Schwein (the pig). Initially unconvincing in testing, the design responded to a few tweaks, the factory content to enter it in a three hour event where it dominated until side-lined by electrical gremlins. Returned to the wind tunnel, the results were inconclusive although suggesting it wasn't significantly different from a 917K (Kurzheck (short tail) and suffered from a higher drag than the 917-LH (Langheck (long-tail)). It was an indication of what the engineers had long suspected: the 917K's shape was about ideal.

Pink Pig Porsche 917-20, Le Mans, 1971.

For the 1971 Le Mans race, the artist responsible for the psychedelia of 1970 applied the butcher’s chart lines to the body which had been painted pink. In the practice and qualifying sessions, the Pig ran in pink with the dotted lines but not yet the decals naming the cuts; those (in the Pretoria typeface), being applied just before the race and atop each front fender was a white pig-shaped decal announcing: Trüfel Jäger von Zuffenhausen (the truffel hunter from Zuffenhausen); the Pink Pig had arrived. Corpulent or not, in practice, it qualified a creditable seventh, two seconds slower than the 917-K that ultimately won and, in the race, ran well, running as high as third but a crash ended things. Still in the butcher's shop livery, it's now on display in the Porsche museum.

Pink Pig Porsche 917-20, 1971.

Scuttlebutt has always surrounded the Pink Pig. It's said the decals with the names of the cuts of pork and bacon were applied furtively were applied, just to avoid anyone demanding their removal. Unlike the two other factory Porsches entered under the Martini and Rossi banner, the Pink Pig carried no corporate decals, the rumor being the Martini & Rossi board, their aesthetic sensibilities appalled by the porcine lines, refused to associate the brand with the thing. Finally, although never confirmed by anyone, it's long been assumed the livery was created, not with any sense of levity but as a spiteful swipe at SERA although it may have been something light-hearted, nobody ever having proved Germans have no sense of humor.

A coffee table in Pink Pig livery built on a M28 Porsche V8 engine (introduced in 1977 for use in the new 928 and, much updated, still in production).

Coffee tables in this form are not uncommon as display or promotional pieces and are sometimes advertised as “the gift for the man who has everything”; whether the pink paint will extend the attraction to many women seems improbable but, despite the perceptions, there are women who share the stereotypically male attachment to cars and their components. Almost all coffee tables built around engine blocks use a glass top so the interesting bits are visible; if there’s thus a flat surface they are as functional as any of the same dimensions. Some however have some of the mechanical bits protruding, usually just for visual impact although there have been some V8s and V12s where the heads are not installed, the open cylinders used as somewhere to place jars of sauces, dressings and such. On this table, the intake manifold extends above the table-top through a surface cut-out so it reduces the usable area but the tubular intake rams are there to be admired. Although all-aluminium, the M28 was built for robustness and was no lightweight: the table weighs some 240 lb (110 kg) and measures (length x width x height) 43 x 20 x 32 inches (1090 x 940 x 432 mm). In an on-line auction in 2024, it sold for US$5300.

In the pink: 1983 Porsche 928S in a “rauchquarzmetallic” wrap. The 928 was the first Porsche to use the M28 V8.

In production between 1977-1995, with a front-mounted, water-cooled V8, the 928 was a radical departure from the configuration of their previous road cars, all air-cooled flat fours or sixes and mostly with a true rear engine layout (the power-plant installed aft of the rear axle). By the early 1970s the Porsche management team had come to believe (1) the fundamental limitations and compromises physics imposed on cars with so much weight at the rear extreme meant such engineering was a cul-de-sac, (2) demand for the by then decade-old 911 would continue to decline and (3) US regulators (then much in the mood to regulate) would soon outlaw rear engines and air-cooling, along with convertibles. As things turned out, by the time of the election of Ronald Reagan (1911-2004; US president 1981-1989), the decision had been taken not to outlaw convertibles but the one-time Hollywood film star (with fond memories of convertibles) had some distaste for “excessive and intrusive regulations” and was elected with the (never explicitly stated but well-understood) agenda to make America great again and a new mood prevailed in Washington, convertibles and much else surviving the expected fall of the axe. The 928 was well-received by the press but, like Toyota’s Lexus which never quite managed to achieve the reputation it deserved because it was “not a Mercedes-Benz” (actually perhaps “not what a Mercedes-Benz used to be”), the 928 suffered from being “not a 911”. Although the 928 joined the list of machines out-lived by those which they were intended to replace, it was a success and in production for some eighteen years although early in the twenty-first century depressed values in the after-market meant it became associated with drug dealers and people with maxed-out credit cards (at some points, certain used 928s were the cheapest 160 mph (260 km/h) cars on the market). The perception has now improved and around the planet there are solid 928 communities although the members display nothing like the devotional, cult-like feelings of the 911 congregation.

1968 Lamborghini Espada Series I with interior re-trimmed in hot pink leather (left) and 1974 Lamborghini

Espada Series III re-painted in baby pink (right). Neither of these colors were at the time available from the factory.

First shown

Geneva Auto Salon in March 1968, the Espada was conventionally engineered (by

the standards of exotic Italian thoroughbreds) but audaciously styled, the

design brief to create something with genuine seating for four while retaining

the dramatic lines which had become a signature of the company which was then

barely five years from having branched out from building tractors. On the prototypes, the designers had flirted with both gullwing doors and an orthodox four-door layout but the conclusion quickly was reached the former was not suited to series-production and the latter would appeal less than a two-door. It was one of

those machines which from some angles was seductively attractive yet from other

aspects could look ungainly but it did work in that although ingress and egress

was compromised, four comfortably could be accommodated and after 1974 Chrysler’s

robust and versatile TorqueFlite automatic transmission became available, further extending the appeal. In what

became a difficult era, it proved Lamborghini’s most successful model with 1226

produced in three series: (176 Espada 400 GT Series I (1968-1969), 578 Espada

400 GTE Series II (1970-1972) & 472 Espada 400 GTS Series III (1972-1978).

1967 Lamborghini Marzal.

Even

at the time some might not have agreed the Espada’s styling was “audacious”

because it verged on the restrained compared with what had the previous year been

shown as a tempting vision of a true, four-seat Lamborghini (prior to the offerings

had been strictly for two or rather cramped 2+2s and there was even a small

runs of a most unusual 2+1 arrangement).

A one-off concept car first shown at the 1967 Genera Auto Salon, the

Marzal was a marvellously impractical design by Bertone’s Marcello Gandini

(1938–2024) which featured two vast gull-wing doors to provide access to what

genuinely was a four-seat interior, noted for the thematic use of

hexagons. It was powered by a

transversely-mounted 2.0 litre (120 cubic inch) straight-six (essentially half

of the company’s V12) which was fitted behind the rear axle, making the

rear-bias in weight distribution rather pronounced. It was one of the most dramatic designs of

the decade and although production was never contemplated, traces of the

silhouette can be seen in the Espada which featured notably less glass than the

Marzal and many have expressed doubts the air-conditioning system able to be

used in the Marzal would in high temperatures have coped with the heat-soak and

build-up.

Bit of a stretch: Model Adriana Fenice (b 1994) in pink stretch top. Stretch fabrics are useful for the industry because they allow a manufacturer to produce a single garment (ie "one size fits all") able to accommodate a ranges of sizes.

Espada

is a Spanish word meaning “sword”, the reference specifically to the blade a

torero uses in bullfighting to kill the unfortunate beast and to this day

Lamborghini still uses terms from the tradition for its models. That’s perhaps surprising given bullfighting

is now not as socially respectable as it was during the 1960s although

disapprobation of the “sport” is

not new and Pius V (1504–1572; pope 1566-1572) as early as 1567 called the

practice: “alien from Christian piety and charity”, “better suited to demons rather than men” and “public slaughter and butchery” fit for paganism but not Christendom and word nerds will be delighted to note Pius V’s

ban on bullfighting was technically a “papal bull”. De

Salute Gregis Dominici (On the Salvation of the Lord’s Flock) was

issued on 1 November 1, 1567 as a formal proclamation with the papal lead seal

(bulla) attached (hence such edicts being known as the “Papal bulls”), the seal

authenticating the document and, as an official decree, it was binding upon Church

and Christian princes. Appalled by the

cruelty, Pius called bullfighting “a sin” and condemned the events as “spectacles of the

devil”, prohibiting Christians from attending or participating under

pain of excommunication. However, like

many papal though bubbles down the ages which never quite make it to the status

of doctrine, his ban was soon ignored and after his death the edict quietly was

allowed to lapse. Predictably, in Spain

and Portugal, where bullfighting had deep cultural & political roots, the bulla

was either ignored or resisted and Philip II (1527–1598; King of Spain

1556-1598), while as devout a Catholic as any man, was known as Felipe el Prudente (Philip the Prudent)

for a reason and quietly he turned the royal blind eye, allowing bullfighting

to continue. Within the Holy See, the king's disobedience of an edict from the Vicar of Christ on Earth would have been disappointing but unsurprising and it was the world-weary Benedict XIV (1675–1758; pope 1740-1758) who best summed-up the church's chain of command: “The pope

commands, his cardinals do not obey, and the people do what they wish.”

1966 Lamborghini Miura P400 re-painted in what most would probably call hot pink but professionals list as fashion fuchsia (Hex: #F400A1; RGB: 244, 0, 161; CMYK: 0,

100, 34, 4). The Miura (1966-1973) was

named after a breed of fighting bull and was the first Lamborghini to borrow an

identity from bullfighting and the first to wear the corporate logo featuring a

bull. In the film The Italian Job

(1969), a Miura is shown being crushed by a bulldozer but that was

filmic trickery using a second, pre-wrecked car and the orange Miura seen driven through the Alps still exists. In many places the film's car is referred to as "tangerine" or "orange", both of which well describe the vivid hue which the factory listed as Arancio Miura (meaning "Miura Orange" although the use in Italian of arancio to mean the color "orange" is untypical, the word used usually in the sense of "orange tree"). In a technological quirk, some film sites call the car "red" but that's a function of some prints or photographs not correctly maintaining the integrity or the original. The term “hot pink” (Hex: #FF69B4; RGB: 255,

105, 180; CMYK: 0, 59, 29, 0) is used very loosely and has become the general

term for bright shades while “baby pink” is used casually of most pastels. In theory, the color palette is infinitely variable

but the practical limitation is the range able to be perceived by the human

eye, illustrated by the announcement in April, 2025 of the “discovery” of a “new

color” (“new” in the sense no human had ever seen it although it may well be

common around the universe).

An artist's depiction of what is closest to "olo", able to be perceived by normal human vision.

Named “olo”, the “new color”

was a deeply saturated blue-green (which many would probably call “teal” or “turquoise”)

and the novelty was it was able to be seen only by test subjects who had laser

pulses fired into their eyes, stimulating specific cells in the retina (a light-sensitive

layer of tissue at the back of the eye responsible for receiving and processing

visual information; it converts light into electrical signals, which are then

transmitted to the brain via the optic nerve, enabling us to see). What the scientists did was aim the beam at

one of the retina’s three cones (there are “S”, “L” & “M” cones, each one sensitive

to different wavelengths of blue, red and green respectively). Because, in normal vision, “any light that

stimulates an M cone cell must also stimulate its neighbouring L and/or S cones

(because its function overlaps with them)”, by using a laser to stimulate

only the M cones, it became possible to “send a colour signal to the brain that never occurs in

natural vision.” Obviously, by adjusting the aim, it may be there are new hues of pink waiting to be discovered although that olo can

be perceived only if laser beams are fired into the observer's eye does limit its use in

fashion and such but the researchers note the findings suggest the

technique could be applied to research into colour blindness. The name “olo” has a marvellously nerdy

origin: It was an allusion to the binary

code “010” which signifies the specific combination of cone cells in the eye

that were stimulated to create the new color perception. Specifically, “0” represents the absence of

stimulation in the short (S) and long (L) cones, while “1” indicates full

stimulation of the medium (M) cones. Math nerds like in-jokes as much as anyone.

SJP (Sarah Jessica Parker; b 1965) in "croissant dress" (left) and a HD (heavy duty) PVC (polyvinyl chloride) dishwashing glove in action (right).

Occasionally, catwalk creations escape and are seen in the wild. In 2022, the actor Sarah Jessica Parker appeared in HBO's (Home Box Office) And Just Like That (2021-2022; a revival of the Sex and the City TV series (1998-2004)), wearing an orange Valentino Haute Couture gown from the house’s spring/summer 2019 collection. It recalled a large croissant, the piece chosen presumably because the scene was set in Paris although it must have been thought viewers needed the verisimilitude laid on with a trowel because also prominent was a handbag in the shape of the Eifel Tower. A gift to the meme-makers, while comments were numerous, admiration for the dress seemed restrained although many were taken by what at first glance appeared to be a pair of PVC (also available in latex) dishwashing gloves in a fetching pink (closer to hot pink than fashion fuchsia); few critics doubted they really were opera gloves from Valentino Haute Couture.

Flamingo's Exotic Dancer's boots in baby pink are available in in calf (left), ankle (centre) and thigh (right) length in a variety of heel and sole heights. Because of the commonality of design elements and interchangeability of components, there's a degree of production-line rationalization which means the range economically can be produced.

Actor Florence Pugh (b 1996) in hot pink Valentino Tulle

gown with Valentino Tan-Go pink patent platform

pumps, July 2022.

The

noun meaning "pale red color, red color of low chroma but high

luminosity" was first noted in 1733 (although "pink-colored" dates from the 1680s),

developed from one of the most common and fancied of the flowers and pink had

come into use as an adjective by 1720. As a physical phenomenon, the color pink

obviously pre-dated the word pink as a descriptor and the earlier name for such

a color in English was the mid-fourteenth century incarnation (flesh-color) and

as an adjective (from the 1530s) incarnate, from the Latin words for

"flesh". These however had

other associations and tended to drift in sense from “flesh-color” &

“blush-color” toward “crimson” & “blood color”; it is thus a discipline to

“translate” even early Modern English.

Lindsay Lohan in pink pantsuit with Valentino’s Rockstud pumps, New York, October 2019.

The

noun pink-eye (and pinkeye) (contagious eye infection) was an invention of US

English from 1882 although, dating from the 1570s, it one meant "a small

eye". The adjectival pink-collar

(jobs generally held by women or those considered characteristically feminine (1977)

or the female workforce generally (1979) was a back-formation based on the

earlier blue-collar, white-collar etc. Pinky

as an adjective (pinkish, somewhat pink) dates from 1790, building on the

earlier pinkish (somewhat pink), noted since 1784. The derogatory

adjectival slang pinko (soon also a noun in this context) was used of those

with social or political views "tending towards “red” (ie sympathetic to

communism, the Soviet Union (USSR) etc) since 1927 although as a metaphor that

had existed at least since 1837. It was

in the context of the time a euphemistic slur; a way of calling someone a

communist (or at least a fellow traveler) without actually saying so. In Australia, old Sir

Henry Bolte (1908-1990; premier of Victoria 1955-1972) would often refer to

the local broadsheet The Age as “that awful pinko rag” although

he wasn’t unique in his critique, the paper’s one-time headquarters known by

many as the “Spencer Street Soviet”.

On any Wednesday.

In

idiomatic use, to be "in the pink" is to be healthy, physically fit, or in high

spirits; to be "tickled pink" dates from 1909 and is to be very happy with

something. The "pink slip" (apparently originally

a "discharge from employment notice" and historically issued on pink

tissue paper (usually as a carbon copy)),

is attested by 1915 and pink slips had various connotations in

employment early in the twentieth century, including a paper signed by a worker

attesting he would leave the labour union or else be fired. The term pink slip came to refer to a wide

variety of documents (in the US it was often the title to a car) provided in

commerce or by government for some purpose (although not all literally were

pink) the term still in some cases enduring for the modern digital analogue. To “see pink elephants”, a euphemism for

those suffering alcohol-induced hallucinations, dates from 1913 when it

appeared in Jack London's (1876-1916) autobiographical novel, John Barleycorn although such things are

not always apparitions. Some

languages such as Chuukese and German use pink but other descendants include

the Afrikaans pienk, the Finnish

pinkki, the Irish pinc, the Japanese pinku (ピンク), the Korean pingkeu

(핑크),

the Marshallese piin̄, the Samoan piniki, the Scottish Gaelic pinc, the Southern Ndebele –pinki, the Swahili -a pinki, the Tokelauan piniki,

the Tok Pisin pinkpela, the Welsh pinc and the Xhosa –pinki.

In the natural environment, pink is all around. Sexy pink orchids in Fuschia (left), an Amazon River Dolphin (Inia geoffrensis, centre) and a pink baby elephant (right).

Pink

elephants are of course hard to find in London but they're rare anywhere. On the internet, there have been claims the

creatures can be found in parts of India, the color the result of the red soil

in the environment, the creatures spraying dust on their hides to protect

themselves from biting insects. However,

it turned out to be fake news, the supporting evidence created with Photoshop

and wildlife experts that while elephants cover themselves in mud, this doesn’t

change the colour of their skin. It's

true there is a rare genetic disorder (technically a form of albinism) which

can result in the skin of young African elephants displaying a slight pink hue

but it's nothing like the vivid hot pink in the Photoshopped fake news. While in London, famous Australian concierge

Elvis Soiza (b 1959 and once a leading figure in the Secret Society of the Les Clefs d’Or)

managed, at remarkably short notice, to procure a pink (painted) elephant to be

led through the streets of Chelsea to delight one of the wives of a visiting

dignitary from the Middle East. Walking a pink elephant through the streets of London has apparently not since been done.

Flying the pink pride flag: Members of Gay Men Fighting AIDS with their pink SPG, London for Pride

Parade, 24 June 1995.

In service

with both the British and Indian armies variously between 1965-2016, Vickers built

234 of the FV433 "Abbot" 105 mm SPG (Self-Propelled Gun) FAV (Field

Artillery Vehicles), using the existing FV430 platform with the addition of a fully-rotating

turret. The factory project code (and

informal military designation) was “Abbot”, in the World War II (1939-1945) British

tradition of using ecclesiastical titles for self-propelled artillery (following

the Bishop, Deacon & Sexton). The

official model name was “L109” but to avoid confusion with

the US-built 155 mm “M109” Howitzer, 144 of which also entered British Army

service in 1965, this rarely was used. While the sight of a

cluster of gay men atop a pink SPG might have frightened a few, the thought of

one in the hands of a pack of lesbians truly is terrifying.

The Playmate-Pink Cars, 1964-1975

Hugh Hefner (1926-2017; founder and long-time editor-in-chief of Playboy magazine) in his 1955 Cadillac Series 62 Convertible. 1955 was Cadillac’s year of “peak dagmar” and

amateur psychoanalysts should make of Mr Hefner’s taste in automobiles what

they will although, sometimes, a Cadillac is just a Cadillac.

The Playboy

Motor Car Corporation was established in New York in 1947 by a pre-war car

dealer who believed there would be much demand for a smaller, less expensive

car than those in the ranges offered by the established manufacturers, almost

all of which essentially differed little from the models which abruptly had

ceased production in 1942. It was in some ways a most modern concept, in-house manufacturing minimized in favor of outsourcing

and, wherever possible, the use of standard, off-the-shelf parts. Conceived as a small convertible with

three-abreast seating, it offered the novelty of a multi-part, retractable hard-top,

something not new but which would not be offered by a volume manufacturer for

almost a decade (before being mostly abandoned for forty years). Like many thousands (literally) of optimistic

souls who have for more than a century succumbed to the temptation of entering

the car business, the hopes of Playboy’s founders were high but many factors

conspired against the project, not the least of which was the car’s tiny size

and under-powered engine; it offered economy in an age when austerity was

becoming unfashionable and not even a hundred were built before the company

entered bankruptcy in 1951. It was an idea ahead of its time and as the success in the 1950s of the smaller, more economical imports (notably the Volkswagen Beetle), even in the prosperous US, demand did exist.

Not Hugh Hefner's sort of car: 1949 Playboy Convertible.

With

that, the Playboy name might have passed forgotten into the annals of the New

York Bankruptcy Court. However, not long

after the company’s demise, Hugh Hefner received a C&D (“cease and desist” letter) from counsel for Stag magazine (a

men’s adventure title), advising a trademark protection suit would be filed

were he to proceed with the release of the magazine he intended to launch with the

title Stag Party. A new name was thus required and after

pondering Pan, Sir, Top Hat, Gentleman,

Satyr & Bachelor, Hefner’s

friend (and Stag Party’s co-founder), Eldon Sellers (1921-2016) (apparently

prompted by his mother who had worked for the failed car company) suggested

it was the ideal name. Hefner agreed

although whether that had anything to do with the clever mechanism with which the little car could be made topless has never been discussed.

With Marilyn Monroe (1926-1962) on the cover, Hefner in 1953 issued the

first edition of Playboy magazine and the rest is history. One

footnote in Playboy’s history is that between 1964-1975, the car gifted to the playmate

of the year (PotY) was usually pink. After

that, the gifts were for some years still given but no longer in pink:

1964:

Donna Michelle Ronne (1945-2004), Ford Mustang convertible.

The

Mustang was the industry’s big hit for 1964, setting sales records which even

now are impressive. It was also highly

profitable, most mechanical parts borrowed from existing Ford lines and the

very platform on which it was built was that of the humble Falcon, introduced a

few years earlier as a compact (in US terms), economy model.

Only the body was truly new but it was “the body from central casting”

and while it didn't (quite) invent the “pony car” segment, it certainly defined it and the linguistic connection lent the sector its name. The lines, which in 1964 created a stir, established the motif which would

be imitated by many and, sixty-odd years on, Mustangs, Dodge

Challengers and Chevrolet Camaros still were all variations of the 1964 original. That original had wide appeal, able to be

configured with relatively small six-cylinder engines (in the sexist language of the age: "secretary's cars") or larger V8s, soon to

include even highly-strung solid-lifter versions, a sign of things to come. Aged 18 at the time of her shoot, Ms Ronne (who modelled as "Donna Michelle") remains the youngest PotY.

The

1964 PotY’s car was finished in a special-order color which anyone could order

but it quickly became known to the public as “Playmate Pink” or “Playboy Pink”

although it was only later Ford added the latter to the option list as code #WT9301. That would be one of four shades

of pink the corporation would offer between 1964-1972 including Dusk Rose (code #M0835 and offered originally on the 1957 Thunderbird), Passionate Pink (code #WT9036

which was part of a Valentine’s Day promotion in February 1968) & Hot Pink

(code #WT9036). Interestingly, regarded as niche

shades, most of the hues of pink rarely appeared on the mass-distribution

brochures and could be viewed only on DSO (Dealer Special Order) charts. Social change, workforce participation and the contraceptive pill combined in the 1960s to let women emerge as influential or even autonomous economic units and Ford was as anxious as any of the cogs of capitalism to attract what was coming to be described as the "pink dollar". The tie-in with Playboy wasn’t the only time

a pink Mustang was a promotional prop, the Tussy Lip Stick Company offering three 1967 Mustangs as prizes for contest winners, each finished in a shade

of pink which matched the lip sticks Racy Pink, Shimmery Racy Pink Frosted & Defroster. Defroster sounds particularly ominous but to set minds at rest, Tussy helpfully decoded the pink portfolio thus:

Racy Pink: "A pale pink".

Racy Pink Frosted: "Shimmers with pearl".

Defroster: "Pours on melting beige

lights when you wear it alone, or as a convertible top to another lip color".

The

fate of the cars is unknown but nerds might note the three prizes were 1967 models while the model (as in the Mustang) in the advertisement is from the 1966 range. That's because the advertising copy had to be made available before the embargo had been lifted on photographs of the 1967 range. The men on Madison Avenue presumably dismissed the suggestion of what might now be thought "deceptive and misleading" content with the familiar "she'll never know".

1965:

Jo Collins (b 1945), Sunbeam Tiger. Now painted red, the car still exists.

Although

from a different manufacturer, the 1965 PotY’s car actually had the same engine

as her predecessor’s gift. Introduced in

1961 with a capacity of 221 cubic inches (3.6 litres), Ford’s small-block V8

(known as the Windsor after the location of the foundry in the Canadian province of Ontario at which it was first

built), it pioneered the use of “thin-wall” casting techniques and, on sale between

1961-2002, would be enlarged first to 260 cubic inches (4.2 litres), then 289

(4.7), 302 (4.9) and 351 (5.8) and installed in everything from pick-up trucks to the

GT40 (#1075) which won the Le Mans 24 hour classic in 1968 & 1969. AC used a 221 as a proof of concept exercise

in what, with the 260, would be released as the first Shelby American Cobras, the most

numerous of which used the 289, the most famous either the 427 or 428 cubic inch (7.0 litres) FE V8.

Ms Collins with her 1965 Sunbeam Tiger Mark I.

In

England, Sunbeam (then part of Rootes Group) had been attracted by the Windsor’s light weight and

compactness, finding, with a little modification and some help from Carroll Shelby (1923–2012), it could (just) fit in the bay of their little Alpine sports car, otherwise never powered by anything larger than a 1.7 litre (105 cubic inch)

four.

Fit it did although one

modification was the inclusion of a hatch in the footwell to permit

a hand to reach one otherwise inaccessible spark plug, an indication of how tight was that fit. However, the project proved successful and

the Tiger sold well although Sunbeam never offered the high-powered versions of

the Windsor Shelby used in the Cobras, the platform really at its limit using

the more modestly tuned units. The US

was a receptive market for the little hot rod and one featured in the Get Smart

TV series, although it’s said that for technical reasons, a re-badged Alpine was

actually used, the same swap effected for the 2008 film adaptation, a V8

exhaust burble dubbed where appropriate, a not unusual trick in film-making. In 1967, after taking control of Rootes Group, Chrysler had intended to continue production of the Tiger (by then powered by

the 289) but with Chrysler’s 273 cubic inch (4.4 litre) LA V8 substituted. Unfortunately, while 4.7 Ford litres filled

it to the brim, 4.4 Chrysler litres overflowed; the Windsor truly was compact. Allowing it to remain in production until the

stock of already purchased Ford engines had been exhausted, Chrysler instead

changed the advertising from emphasizing the “…mighty Ford V8 power plant” to

the vaguely ambiguous “…an American V-8 power train”. The badges fitted to the cars reflected the change in corporate ownership, switching from "Powered by Ford 260" to "Sunbeam V8" although cars sold South Africa or certain European countries were all designated "Alpine 260" or "Alpine 289" because the names "Tigre" & "Tiger" were already trademarked by other manufacturers. Rootes were able to use the Alpine name in France because it had sold there the original Alpine a year before the French manufacturer Alpine had begin production.

1966:

Allison Parks (1943-2010), Dodge Charger.

Detroit in the 1930s had produced fastbacks because "streamlining" had become a fashion and in the 1940s even had mainstream ranges of two & four door models but the fad proved brief. However, there was a comeback because by the early 1960s experience

on the NASCAR ovals had demonstrated how much more aerodynamically efficient

were steeply sloped rear windows compared with the more upright “formal roof” (which would come to be described as “notchback”) that designers and public alike had preferred for the additional headroom the packaging

efficiency created. So buoyant was the

state of the US industry at the time, the solution sometimes was to offer both and the most

slippery form of all was the fastback, a roofline which extended in one curve

from the top of the windscreen all the way to the tail. As a generation of Italian thoroughbreds had

shown, the fastback could be a dramatic and aesthetic success on smaller machines but on

the big Americans, it was a challenge and one never really solved

on the full-sized cars although the by the late 1960s, a formula had been found for

the intermediates, necessitated by the shape delivering higher speed and lower fuel consumption on the NACSAR ovals.

Electroluminescent instruments in 1966 Dodge Charger.

In

1966, the formula was still being mixed and while the Dodge Charger’s

wind-cheating tail (after some tweaks) delivered the extra speed, the slab-sidedness

attracted criticism and, after an initial spurt, sales were never

impressive and it wouldn’t be until the revised version was released to acclaim

in 1968 that the promise was realized.

In fairness, the 1966 Charger, while not as

svelte as its successor, was

a better interpretation of the big fastback than some others, notably the truly

ghastly Rambler (later AMC) Marlin.

Mechanically, the

Charger was tempting, the top engine (though not the biggest, a tamer

440 cubic inch (7.2 litre) V8 also available) option the newly released 426 cubic inch

(7.0 litre)

Street Hemi which was a very expensive, slightly

detuned race

engine and the dashboard featured Chrysler’s intriguing electroluminescent instruments

which, rather than being lit with bulbs, deployed a

phenomenon in which a material emits light

in response to an electric field; the ethereal glow much admired.

The much admired "twin bucket rear-seats with full-length console".

It's said the 1966 PotY wanted something roomy and practical with which to take her family

to swimming practice so the spacious Charger was a good choice and the rear bucket seats, although

separated by a full-length console, could be folded flat, creating a surprisingly

capacious compartment. Wisely, the

Playboy organization didn’t give her a Hemi Charger, the dual quad monster

inclined to be noisy, thirsty and even a little cantankerous (although if running late for swimming practice there would have been advantages), the pink car instead fitted with a 383 cubic inch (6.3 litre) V8, the engine in the era nominated by Chrysler’s

engineers as the best all-round compromise, the two-barrel version

their usual recommendation, a four-barrel edition available for those prepared to sacrifice

economy for performance. The fate of the

car is unknown.

1967:

Lisa Baker (b 1944), Plymouth Barracuda fastback.

However

ungainly the fastback may have appeared on the Charger, it worked well on the

smaller Barracuda although there are students of such things who maintain the almost

Italianesque lines of the notchback version are better and there was a

convertible too, matching the coachwork by then offered on the Mustang. What all agreed however was the second series

Barracuda, released in 1967, was a vast improvement on its frumpy predecessor,

now noted mostly for the curiosity of its huge, wrap-around rear-window. Things could have been different because the

original Barracuda, using the same concept as the Mustang (a poetic form disguising a prosaic structure), was actually released a few weeks before the sexy

Ford and was in some ways a superior car but it had nothing like the appeal, being so obviously based on an economy car whereas the Mustang better hid its humble origins.

Ms Baker with Barracuda.

The

second series Barracuda looked much more attractive although, being less

changed underneath, didn’t fully emulate the “long hood, short deck” motif with

which the Mustang had created the pony car template.

Still, its reception in the market encouraged Chrysler and soon, to match the now widened Mustang, big block

engines began to appear. The Barracuda was not actually widened but this was the 1960s and though Chrysler couldn’t easily

install a big-block, they could with difficulty and so they did although the 383

was a tight fit and compromises were required, the exhaust system a little

restrictive and niceties like power steering weren’t offered; with the big

lump sitting over the front wheels, at low speed they did demand strength to

manhandle. Almost 2000 were built with the 383 V8 but

there were some who wanted more and in 1969, in a package now called ‘Cuda, a

few were fitted with the 440. At first

glance it looked a bargain, the big engine not all that expensive but having

ticked the box, the buyer then found added a number of "mandatory

options" so the total package did add a hefty premium to the basic

cost. The bulk of the 440 was such that

the plumbing needed for disc brakes wouldn’t fit so the monster had to be

stopped with the antiquated drum-type and again there was no space for power

steering. The prototype built with a

manual gearbox frequently snapped so many rear suspension components the

engineers were forced to insist on an automatic transmission, the fluid cushion

softening the impact between torque and tarmac but, in a straight line, the

things were quick enough to entice almost 350 buyers. To this day the 440 remains the second biggest displacement engine Detroit put in a pony car, only the 455 (7.5 litre) Pontiac used in the Firebird and Trans-Am was larger.The

1969 440s weren’t exactly anti-climatic but true megalomaniacs had in 1968 been

more impressed when Plymouth again took the metaphorical shoehorn used to fit the 383 and installed

the 426 Street Hemi, 50 of which were built (though one normally reliable

source claims 70) and, with fibreglass panels & much acid-dipping to reduce weight, there was no pretence the things were

intended for anywhere except a drag strip, living out sometimes brief lives in quarter mile (402m) chunks.

The power-to-weight ratio of the 1968 Hemi ‘Cudas was the highest of the

era but lurking behind the Sturm und Drang stirred

by the big blocks was one of the best combinations of the era: The 'Cudas

fitted with Chrysler's 340 cubic inch (5.6 litre) (LA) small block V8 were

superior machines except in straight line speed and the visceral reaction a Hemi can induce.

Dior Rouge 999.

The

Hemi ‘Cuda reached its apotheosis in 1970 when, on a unique widened (E-body) platform,

it and the companion Dodge Challenger were finally fully competitive pony cars. Unfortunately, just as the 1967 Barracuda

would likely have been a bigger success if released in 1964, so the 1970 car

was three years too late, debuting in a declining market segment. In 1970, an encouraging 650 odd Hemi ‘Cudas

were sold but the next year, under pressure from the soaring costs of insuring

the things, sales collapsed, barely reaching three figures. The smaller engined versions fared better but

the emission & safety regulations added to the negative market forces and

the first oil shock in 1973 was a death knell, both the Barracuda and

Challenger cancelled in 1974, the four-year E-body programme booking a significant financial loss. In the agonizing reappraisal undertaken in the aftermath of what was labeled "a debacle", careers were said to have suffered. It was as an extinct species the later ‘Cudas

achieved their greatest success... as used cars. In 2014, one of the twelve 1971 Hemi ‘Cuda

convertibles sold at auction for US$3.5 million and in 2021, another attracted

a bit of US$4.8 million without reaching the reserve. If it survives, the 1967 PotY’s pink

Barracuda wouldn’t benefit from quite that appreciation but it would have some

appeal and there were reputedly another ten pink cars built for the occasion,

all from the one California plant, the paint code #999, which, coincidently, is

shared with Dior’s cor Rouge 999 lip stick and nail enamel. Red rather than pink, the Dior's 999 reference was borrowed from the gold industry, a purity of 99.9-something percent as pure as gold gets. Known also as "24 karat" or "pure gold", because of the softness, it's not suitable for all decorative or industrial uses but is a required standard for investment purposes such as bars, bullion or coins. The 999 standard permits an alloying with 0.1% impurities or other metals (usually silver, copper or lead) and some metals exchanges even specify the proportion of the other metals which may be included in the 0.1%. Unfortunately, Plymouth's paint code #999 wasn't unique to the the pink Barracudas, "999" being the corporate identifier for "special orders" (ie any color not on the RPO (regular production option) chart).

1968: Angela

Dorian (b 1944), AMC AMX.

Before

Tesla, American Motors Corporation (AMC) was the last of the "independents" (some of which formed agglomerations in an attempt to survive) which tried to compete with Detroit’s big three, GM (General Motors), Ford

& Chrysler. In the post-war years

this was mostly a struggle and AMC’s brightest years had come in the late

1950s when, then run by George Romney (1907–1995 and father of Mitt Romney (b

1947; Republican nominee for US president 2012)), the company began to

compete against small, imported cars, then a market segment in which the big

three offered no domestically produced vehicles. That however changed in the early 1960s and

AMC’s halcyon days soon ended although they continued for years along the road

to eventual extinction and one of their more interesting ventures was the

short-lived AMX (1968-1970).

The AMX

exemplified the AMC approach in that it was conjured up something new by taking

an existing model and, at low cost, modifying it to be something quite different, an

approach which, for better and worse, they were compelled to follow to the

end. The AMX was a short-wheelbase,

two-seater version of AMC’s Javelin pony car which, introduced in 1967 to

contest the then booming segment, had been well-reviewed by the press

and, despite the latter-day perception of its lack-lustre performance in the

market, sometimes out-sold the Barracuda and actually out-lived it by a few

months but unlike some Barracudas (actually the 'Cuda derivative), neither Javelins nor

AMXs command multi-million dollar prices at auction. The

corporation originally used the AMX name (standing for “American Motors

experimental”) for a “concept car” and two show cars (somewhat misleadingly at

the time referred to as “prototypes”) which toured the show circuit in

1966-1967. All were a radical departure

from the staid image associated with the economical, practical vehicles on

which the company had built its reputation (and most of its profits) but the

response was positive and with the post-war baby boom having created a large

number of males aged 17-25 who were the most affluent young generation in history,

AMC decided to enter the “sporty” car market.

In fairness, at the time, it would have seemed not only a good idea but

also an obvious one given the extraordinary success of machines like the Ford

Mustang & Chevrolet Camaro. Like

many manufacturers, AMC liked three letter designations and they also had a

trim package called “SST” which, according to internal documents, stood for “Super

Sports Touring” and not “Stainless Steel Trim” as has been suggested

(although use was made of the metal for some of the bright-work so the assumption

was not unreasonable). Doubtlessly AMC

expected some positive association in the public mind with the SST (supersonic

transport) projects several US aerospace manufacturers were in the era pondering as competition for the Anglo-French Concord(e).

AMX 36-24-35, post-restoration, 2015.

The AMX was an interesting and even a "brave" (in the sense Sir Humphrey Appleby (the fictional senior bureaucrat in the BBC's Yes Minister (1980-1984) & Yes, Prime Minister (1986-1988) series) might

have used the word) innovation, a two-seat coupé added to a market in which

there was no similar model (Chevrolet’s Corvette was a true sports car), the last attempt

at such a thing the two-seat Ford Thunderbird (1955-1957) which had been retired

and replaced by a vastly more successful four-seat version (although in 1962-1963 Ford did produce a two-seat version called "Sports Roadster" but demand was muted). That was not encouraging but AMC persisted,

able to leverage its resources and produce lines at lower cost than the big

three could manage. Like the

Javelin, the AMX was a piece of typically solid AMC engineering which enjoyed some success in

competition and quixotically, two dozen were assembled in Australia in

right-hand-drive configuration, sold under the old Rambler name which had so

well served George Romney, the marque lingering on there for a few more

years where, remarkably to Americans, it was marketed as a "prestige" product (on the basis of being "American", the big US cars enjoying a solid reputation for comfort, power and reliability). However, the costs involved in

maintaining the shorter AMX platform were too great and when a revised Javelin

was released in 1971, the AMX name was used to denote the high-performance version. The Javelin too would be axed in 1974 but AMC

continued to use the AMX name until 1980.

What George would never have allowed.

By

1968, the deeply religious George Romney was long gone from AMC, having moved

into Republican politics; like his time in the car business, his second career

had its ups and downs and (like his son and many others) he never realized his goal of reaching the White

House. Had he still been in the chair, it may be that never would he have countenanced the idea of AMC getting mixed up with Playboy magazine and,

even if persuaded, probably would have drawn the line at the PotY’s vital statistics blatantly being celebrated. As

it was, with no Mormon veto, the AMX, one of several

said to have been painted “Playmate Pink” was delivered to Ms Dorian

with a plaque on the dashboard engraved AMX 36–24–35 (the numbers verified by the staff at Playboy, experts in such matters and for those used to the metric system, it would have been expressed in a rounded 90-60-90).

Walther PPK.

Ms

Dorian too had her ups and downs, eventually parting with AMX 36-24-35 after forty-two years but keeping

the Walther (9mm) PPK handgun which had been a gift from a friend, the film-maker

Roman Polanski (b 1933), the two having met when Dorian appeared as a recovering

heroin addict in Polanski's

Rosemary's

Baby (1968). She was also a friend of

the director's then wife Sharon Tate (1943-1969) and in August 1969, after followers

of cult leader

Charles Manson (1934-2017) murdered the eight months pregnant

Tate (and four others), Polanski gave his personal Walther PPK to Dorian for

self-protection and it was with this that in 2010, after an argument, a 66 year-old Angela

Dorian shot her husband of two decades. He survived the shooting and was

quoted by the press

lamenting "

I loved her for nearly 25 years. A divorce

would have been sufficient, not a bullet...", which, in the circumstances, does seem generous. Charged with attempted

murder (later reduced to attempted voluntary manslaughter to which she pleaded

no contest), she received a nine year sentence and was released on

parole in

April 2018. AMX 36-24-35 also had its ups and

downs, repainted (like many of the playmate cars) in something less

eye-catching before being found in a dilapidated state. It’s since been restored to its original pink splendor and remains in its original configuration,

equipped

with the base (short-deck) 290 cubic inch (4.8 litre) V8, automatic

transmission, air conditioning, tilt wheel, AM radio & 8-track stereo

player and the optional rear bumper guards.

It remains unique as a PotY car but the factory’s records do list one

other “Playmate Pink” AMX, “special-ordered” late in 1968 by a dealership in Potosi,

Missouri and it would have been a bit quicker, running the “AMX”

390 (6.4) (a short deck version of the AMC V8 unique to the AMX), coupled with an automatic transmission, the “GO" option (a

high-performance & dress-up package), air conditioning, and leather trim.

1969: Connie Kreski (1946-1995) and Shelby American Mustang GT500 with the ultimate

hood (bonnet) ornament between the NACA

ducts.

A pink Shelby Mustang is a rarity and Ms Kreski was of course lovely but for some, eyes will be drawn to her

bare feet and

true aficionados will admire her Morton's toe (also as Royal toe or Greek foot),

a congenital condition in which the second toe is longer than the big toe, the

consequence of a shorter first metatarsal bone. Her case was slight enough probably to have been asymptomatic but she

may have noticed increased pressure on the joint beneath the second toe if

wearing especially unsympathetic shoes (as the stilettos sometimes worn by

Playboy's models sometimes were). The

condition was first described by US orthopedic surgeon Dudley Joy Morton

(1884–1960) in the paper Metatarsus

atavicus: the identification of a distinct type of foot disorder which

appeared in the Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery (Boston), 1927, volume 9. It was among the conditions he grouped as Morton's

triad (known also as Morton's syndrome or Morton's foot syndrome).In

their run of half a decade, Carroll Shelby’s Mustangs were transformed from race

cars which, conveniently, could be road-registered and driven to the track,

into elaborately embellished, luxuriously equipped cars usually just a little

more powerful than those upon which they were based yet managing still to look faster still. In 1965, Shelby was aware of the Mustang’s

potential in competition and looking for a profitable line to sell, the new seven litre (427 & 428 cubic inch) Cobra giving every indication it would become the

loss-making venture it proved (although they became an extraordinarily profitable investment for anyone buying at the right point).

Connie Kreski in sensible shoes. The 1969 & 1970 Shelby Mustangs featured an impressive five NACA ducts on the hood (three to scoop air in, two to allow it to escape).

Shelby American created the first of their Mustangs in 1965, using basic, fastback cars sent by

Ford to the factory in Venice Beach, the facilities later moved to 6555 West

Imperial Highway (now the Qantas freight terminal) adjacent to Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) when more

space was required. All the cars built

in 1965-1966 used the familiar Windsor 289 in essentially the same sate of tune

as the Cobras and the drive-train was beefed-up to handle both

the additional output and the lateral forces encountered in the extremes of competition. The Cobra DNA in the early

Shelby Mustangs was thus no affectation and the “Cobra” name was often applied

to the cars, both in marketing materials and on parts prominently displayed. The cars however were as much about what was

left out as what was put in. Shelby had

been a race driver (winning the 1958 Le Mans 24 Hour) and understood the significance of lightness which improved performance, tyre wear & fuel

consumption and reduced the stresses to which mechanical components were

subject so, reflecting his philosophy that a sports car was one “with noting on

not there for the purpose of making it go faster”, the Shelby Mustangs were

stripped of whatever wasn’t essential, including carpets and sound deadening. That helped the performance on the track but

did make driving a noisy, uncomfortable experience. At the time, the 1965 Shelby Mustang GT350

was memorably described as “a brand new, clapped-out racing car”. Sometimes the weight-saving was necessitated

by the letter of the law, the rear seat removed so the things could be defined

as “two seat sports cars” and thus be eligible for competitions run by the

Sports Car Club of America (SCCA), a modification which proved handy because it

allowed the spare tyre to be kept where once the seat sat, improving weight

distribution. It was definitely not for

everyone but 562 were sold, 34 of which were the specially prepared GT350R which

for three years won its SCCA championship class.

The

retreat from rawness began in 1966, the need to homologate for competition

having been satisfied. An automatic

transmission became optional and the cars, now labelled as Shelby GT350s, were

no longer fitted with some of the suspension, exhaust and other modifications

which had distinguished the 1965 run although the rarely-ordered option of a

Paxton supercharger (a version of the old Mcculloch unit rebranded after the company was absorbed by STP) was added to a growing list. Famously too, in that year some 1000 GT350Hs

were built on order from the Hertz Rental Car Company and there are stories,

some of which may be true, of them being rented on Saturday, raced on Sunday

and returned on Monday. These days, the deal with Hertz might be called a “related party transaction", Ford (a

big holder of Hertz stock) having prevailed on their management to place the

order.

Lindsay Lohan in Michael Kors (b 1959) pink keyhole dress for the release of Speak (2004), New York City, 7 December, 2004.

In

1967, the trend towards civility continued, a prototype convertible built (although

technical problems prevented production) and all were now full-fledged road

cars, Shelby’s interest now entirely in cheque-books rather than chequered flags. Ford had given the 1967 Mustangs a wider

platform so the 390 cubic inch (6.4 litre) big-block (FE) V8 could be fitted

and this enabled Shelby to introduce the GT500 which used the 428, until then something used effortlessly and quietly to propel luxury

sedans and coupés. Shelby used the 428 in "Police Interceptor" specification, added the brace of four barrel carburetors and tuned things a little but the quest had shifted from

raw performance to making slightly faster versions of Mustangs which looked

faster still and could attract a higher price. Later GT500s used Ford's factory supplied 428 CobraJet which, with a single four-barrel carburetor was more powerful.

1967 Shelby GT500 (427), the one-off "Super Snake".

In their original production schedules, Ford had planned in 1967 to offer a Mustang with a detuned version (a single four barrel carburetor and hydraulic valve lifters) of the 427 but none ever left the line and the last of the 427s instead appeared in a run of 1968 Mercury Cougars, all with automatic transmissions. However, in a glimpse of

what might have been (and was not quite realized even when the Boss 429 Mustang later appeared), Shelby did build one

GT500 with a 427 FE. With fractionally

less displacement than the 428, the 427 was a genuine racing engine, more

oversquare in configuration with enhanced lubrication and a strengthened bottom

end; it twice won at Le Mans and had been intended as an option for the 1968 Mustangs before the accountants worked out quite how expensive that would