Primate (pronounced prahy-meyt

or prahy-mit)

(1) In the

ecclesiastical hierarchy, an archbishop or bishop ranking first among the

bishops of a province or country (in this context usually pronounced prahy-mit).

Primate is a title or rank bestowed on some archbishops in some Christian

churches and can, depending on tradition, denote either jurisdictional

authority or mere ceremonial precedence.

(2) In zoology,

any of various omnivorous mammals of the order primates (including simians and

prosimians), comprising the three suborders anthropoidea (humans, great apes,

gibbons, Old World monkeys, and New World monkeys), prosimii (lemurs, loris,

and their allies), and tarsioidea (tarsiers), especially distinguished by the

use of hands, varied locomotion, and by complex flexible behavior involving a

high level of social interaction and cultural adaptability: a large group of

baboons is called a congress which,

to some, makes perfect sense.

(3) A

chief or leader (archaic).

1175-1225:

In the sense of "high bishop, preeminent ecclesiastical official of a

province" having a certain jurisdiction, as vicar of the pope, over other

bishops in his province, primate is from the Middle English primate & primat, from the Old French primat

and directly from the Medieval Latin primatem

(church primate), a noun use of the Late Latin adjective primas (of the first rank, chief, principal) from primus (first). The meaning "animal of the biological

order including monkeys and humans" is attested from 1876, from the Modern

Latin Primates, the order name (linnæus),

the plural of the Latin primas; so

called for being regarded as the "highest" order of mammals (the

category originally included bats, representing the state of thought in biology

at the time).

As an adjective, prime dates from

the late fourteenth century in the sense of "first, original, first in

order of time" from the Old French prime

and directly from the Latin primus (first, the first, first part (figuratively

"chief, principal; excellent, distinguished, noble") from the Proto-Italic

prismos & priisemos, superlative of the primitive Indo-European preis- (before), from the root per (beyond;

before; forward), hence the sense "in front of, before, first, chief". It was the source also of the Italian and

Spanish primo and thus a doublet of primo.

The meaning "of fine quality; of the first excellence" is from

circa 1400. The meaning "first in

rank, degree, or importance" was first noted in English circa 1610 whereas

in mathematics (as in prime number), it wasn’t in the literature until the

1560s. The prime meridian (the meridian

of the earth from which longitude is measured, that of Greenwich, England) was

established in 1878. Prime time which originally

was used to describe "spring time" is attested from circa 1500. The use in broadcasting in the sense of a "peak

tuning-in period" dates from 1961.

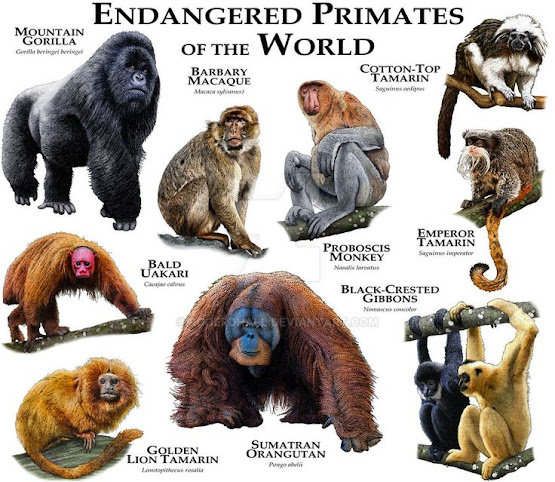

Some endangered primates.

As a noun prime referred to the "earliest

canonical hour of the day" (6 am), from the Old English prim and the Old French prime or directly from the Medieval

Latin prima "the first service"

from the Latin prima hora (the first

hour (of the Roman day)), from the Latin primus

("first, the first, first part").

In classical Latin, the noun uses of the adjective meant "first

part, beginning; leading place". The

noun sense "apostrophe-like symbol" exists because the symbol ′ was

originally a superscript Roman numeral one.

By extension, "the first division of the day" (6-9 am) was an

early-thirteenth century form whereas the sense of "beginning of a period

or course of events" is from the late fourteenth. From the notion of "the period or

condition of greatest vigor in life" there came by the 1530s the specific

sense "springtime of human life" (taken usually to mean the ages around

21-28 (the division of live in seven-year chunks a noted motif in English) is

from the 1590s and at about the same time, prime came to mean "that which

is best in quality, highest or most perfect state of anything".

The use as a verb dates from the 1510s,

an invention by the military to describe the process (fill, charge, load)

required before a musket or other flintlock weapon could be discharged, the assumption

being this was derive from the adjective.

From this by circa 1600 evolved the general sense of "perform the

first operation on, prepare something for its intended purpose” (applied especially

to wood to make ready for painting)".

To prime a pump is noted from 1769 and meant to pour water down the tube

to saturate the sucking mechanism which made it draw up water more readily. This was later adopted in public finance and

economics to describe what is now usually called fiscal stimulus (the idea

being a little government money attracting more private investment. The suffix -ate was a word-forming element

used in forming nouns from Latin words ending in -ātus, -āta, & -ātum (such

as estate, primate & senate). Those

that came to English via French often began with -at, but an -e was added in

the fifteenth century or later to indicate the long vowel. It can also mark adjectives formed from Latin

perfect passive participle suffixes of first conjugation verbs -ātus, -āta, & -ātum (such as desolate, moderate & separate). Again, often they were adopted in Middle

English with an –at suffix, the -e appended after circa 1400; a doublet of –ee.

Lindsay Lohan and a large primate, King Kong premiere, Loews E-Walk and AMC Empire 25 Theaters, New York City, December 2005.

The Roman Catholic Church

In the Roman

Catholic Church, a Primate is almost always an Archbishop though the title is

occasionally bestowed on the (Metropolitan) bishop of an Episcopal see who has

precedence over the bishoprics of one or more ecclesiastical provinces of a

particular historical, political or cultural area. Also sometimes created are primates where the

title is entirely honorific, granting only precedence in on ceremonial

occasions and, in the case of the Polish Primates, the privilege of wearing

cardinal's crimson robes (though not the skullcap and biretta). The Vatican likes the old ways and many

primates are vested not in the capitals of countries but in those places which

were the centres of the country when first Christianized. For that reason there still exists the Primate

of the Visigothic Kingdom, and the Primate of the Gauls.

Some of

the leadership functions once exercised by Primates have now either devolved to

presidents of conferences of bishops or to Rome itself. Modern communications as much as reform of

canon law have influenced these developments and most changes were effected

between the publication of the Code of Canon Law in 1917 and the late

twentieth-century implementation of Vatican II’s more arcane administrative

arrangements. Rome

has never seemed quite sure how to deal with England. Unlike in the secular US, where the Holy See’s

grant of precedence to the Archbishop of Baltimore dates from 1848, the

Archbishop of Westminster has not been granted the title of Primate of England

and Wales but is instead described as that of Chief Metropolitan. Rome has never exactly defined the

implications of that though it has been suggested the position is “…similar to

that of the Archbishop of Canterbury.” Most

helpful.

If the

position in England remains vague, that of some of the orders is opaque. The loose structures of the Benedictine

Confederation made Pope Leo XIII (1810–1903; pope 1878-1903) exclaim that the

Benedictines were ordo sine ordine

(an order without order), something about which he subsequently did

little. The Benedictine Abbot Primate

resides at Sant'Anselmo in Rome and takes precedence of all other abbots and is

granted authority over all matters of discipline, to settle difficulties

arising between monasteries, to hold a canonical visitation, exercise a general

supervision for the regular observance of monastic discipline. However, his Primatial powers permit him to

act only by virtue of the proper law of the autonomous Benedictine congregations,

most of which does not exist. Charmingly,

the Benedictine Order appears still to operate as it’s done for the last few

centuries, untroubled by tiresome letters from Rome although other orders have

embraced modern ways. The Confederation

of Canons Regular of St Augustine democratically elects an Abbot Primate,

though his role, save for prerogative reserve powers, is ceremonial.

The Church of England

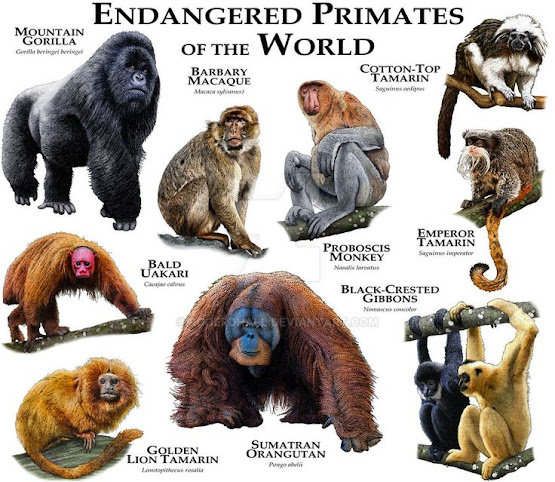

Some endangered Primates at the Lambeth Conference, London, 1930. The once almost exclusively white, male and middle class world of Anglican bishops has in recent decades become increasingly black, evangelical and even female. It seems likely it may also become increasingly gay. Although rarely spoken of, it's an open secret the Anglican church in England depends for its operation on its many gay clergy and it may be it will require only the natural processes of generational change for gay bishops to become an accepted thing. Before that, a state of tolerance or peaceful co-existence may be next step.

Anglican usage styles the bishop who heads an independent church as its primate, though they always hold some other title (archbishop, bishop, or moderator). In Anglicanism, a primate’s authority is not universally defined; some are executives while others can do little more than preside over conferences or councils and represent the church ceremonially. However,

the when the Anglicans convene a Primates' Meeting, the chief bishop of each of

the thirty-eight churches that compose the Anglican Communion acts as its

primate, though they may not be that within their own church. For example, the various United Churches of the

sub-continent are represented at the meetings by their moderators though they

become primates for the purposes of Anglican conferences. Primates are thus created for

photo-opportunities.

Winds of change: Primates at the Global Anglican

Future Conference (GAFCON), Jerusalem, 2018.

In both the Churches of England and

Ireland, two bishops have the title of primate: the archbishops of Canterbury

and York in England and of Armagh and Dublin in Ireland. The Archbishop of Canterbury, considered primus inter pares (first among equals) of

all the participants, convenes meetings and issues invitations. The title of primate in the Church of England

has no direct relationship with the ex-officio right of twenty-six bishops to

sit in the House of Lords; were the church to do away with the title, it would

not at all affect the constitutional position.

The

Orthodox Church

In the

Orthodox Church, a primate is the presiding bishop of an ecclesiastical

jurisdiction or region. Usually, the

expression primate refers to the first hierarch of an autocephalous or

autonomous Orthodox Church although, less often, it’s used to refer to the

ruling bishop of an archdiocese or diocese. In the first hierarch, the primate

is the first among equals of all his brother bishops of the jurisdiction or

diocese of which he is first, or primary, hierarch, and he is usually elected

by the Holy Synod in which he will serve. All bishops are equal sacramentally, but the most

important administrative tasks are undertaken by the bishop of the most honored

diocese. The primate of an autocephalous

church supervises the internal and external welfare of that church and

represents it in its relations with other autocephalous Orthodox churches,

religious organizations, and secular authorities. During liturgical services, his name will be

mentioned by the other bishops of the autocephalous church and the primate

mentions the names of the other heads of autocephalous Orthodox churches at

Divine services.

The liturgical duties vary between jurisdictions

but, normally, the hierarch is responsible for such tasks as the consecration

and distribution of the Holy Chrism and providing the diocesan bishops with the

holy relics necessary for the consecration of church altars and holy antimins. To this may extend other administrative

duties including convening and presiding over the meetings of the Holy Synods

and other councils, receiving petitions for admission of clergy from other

Orthodox churches, initiating the action to fill vacancies in the office of

diocesan bishops, and issuing pastoral letters addressed to the bishops,

clergy, and laity of the Church. He will

also advise his brother bishops, and when required, submits their cases to the

Holy Synod. He has the honor of pastoral initiative and guidance, and, when

necessary, the right of pastoral intervention, in all matters concerning the

life of the Church within the structure of the holy canons.