Align (pronounced a-line)

(1)

To arrange in a straight line; adjust according to a line.

(2)

To bring into a line or alignment.

(3)

To bring into cooperation or agreement with a particular group, party, cause

etc; to identify with or match the behavior, thoughts etc of another person.

(4)

In radio transceiving, to adjust two or more components of an electronic

circuit to improve the response over a frequency band, as to align the tuned

circuits of a radio receiver for proper tracking throughout its frequency

range, or a television receiver for appropriate wide-band responses.

(5)

To join with others in a cause.

(6)

In computing, to store data in a way consistent with the memory architecture ie

by beginning each item at an offset equal to some multiple of the word size.

(7)

In bioinformatics, to organize a linear arrangement of DNA, RNA or protein

sequences which have regions of similarity.

Circa

1690: From the Middle English alynen

& alinen (copulate (of wolves

& dogs)), from the Middle French aligner,

from Old French alignier (set, lay in

line (sources of the Modern French aligner)).

The construct à (to) + lignier (to line) was from the Latin lineare (reduce to a straight line) from

linea (line). The French spelling with the -g- is un-etymological,

and aline, the early alternative spelling in English is long obsolete and was

never revived as US English.

The

transitive or reflexive sense of "to fall into line" is attested from

1853 with the use in international relations first noted in 1923 in the sense

of (return to previously aligned positions) in reference to European

international relations and use spiked after 1933 in the League of Nations in

discussions about the disputes which would from then only worsen. The noun alignment (arrangement in a line)

dates from 1790 and misaligned (faulty or incorrect arrangement in line) was

originally used in engineering, documented from 1903 although, curiously,

realign (align again or anew), a back-formation of realignment was in common

use in railway construction by the mid 1800s.

References to the Non-Aligned Movement (formalized in 1961), appeared in

documents in 1960 although the concept of geopolitical non-alignment was much

discussed after 1934 in debates in the noble but doomed League of Nations

(1920-1946 (although a moribund relic after 1940)).

The

Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a group of states with some one-hundred and twenty members. It began during the cold war as a loose organization of countries, not formally aligned either with Washington or Moscow, the centres of the two major power blocs. The NAM was formed in Belgrade in 1961, the project of Jawaharlal Nehru (1889–1964; Prime-minister of India 1947-1964), Sukarno (1901–1970; president of Indonesia 1945-1967), Gamal Abdel Nasser (1918–1970; president of Egypt 1954-1970) and comrade Josip Broz Tito (1892–1980; prime-minister or president of Yugoslavia 1944-1980). The cross-cutting cleavages of the cold war meant the NAM was never wholly synonymous with the third world but those nations provided the bulk of the organization’s membership. Nor was the NAM politically monolithic, the organization doing little to reduce tensions between members Iran & Iraq or India & Pakistan (NATO notably more successful in suppressing things between squabbling members), its most noted fracture over the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan in 1979; while some Soviet allies supported the invasion, others (particularly Islamic states) condemned it.

The NAM: members in dark blue, those enjoying observer status in light blue.

Quite

what role the NAM has fulfilled since the end of the Cold War is not

clear. Its ongoing survival may be

nothing more than bureaucratic inertia or the tendency for political structures

to live on beyond the existence of the purpose for which they were created, a

phenomenon noted in academic literature in both political science and

organisational studies. So, sixty years

on, it still exists, even conducting virtual summits during the COVID-19 pandemic

although it’s been many years since anything said in its forums attracted much

attention. Of late however, as the

building blocks of the New Cold War have taken shape, there’s been much

speculation about the future composition of the NAM as a bi-polar arrangement

consisting of (1) the West and (2) the BRICS seems to be coalescing. The origin of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China (South Africa

added later)) was in an economist’s paper (2001) discussing the high-growth

economies which showed the greatest potential and the organisation has recently

added Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab

Emirates. The claims by the BRICS

secretariat that what is envisaged is a “multi-polar world” are interesting in

as much as they’re being made rather than for their credibility but there are

many not unhappy at prospect of a bi-polar planet being formalized and the form

in which this emerges will be dependent on how certain nations in the NAM

decide to re-align. While there’s still

a degree of medium-term predictability about Russia, China and other usual

suspects, players like India and Brazil (which can be open to temptation and

civilizing influences) and may emerge as a political dynamic, either as

horse-traders or fence-sitters.

The

overlay: the first, second & third worlds

First World Blue: Essentially the anti-communist bloc of the cold war. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the definition has shifted to include any country with stable (ie non-violent) political systems, some degree of democracy, a legal system which at least pretends to adhere to the rule of law, a market-based economy and a high standard of living. Best thought of as the rich world, these are the countries in which it’s (usually) safe to drink the tap water.

Second

World Red: The Second World referred to the nominally communist or socialist

states mostly under the influence of the Soviet Union. Soviet control varied from actual satellite

states to those merely in degrees of sympathy with Moscow. Relationships were often fractious, the most

celebrated tiff being the Sino-Soviet split.

Third

World Green: Originally, the term was a political construct to define countries

that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Communist Bloc but, even

among scholars of political economy, there never emerged a consensus about just

which countries constituted the third world.

The most used, but least defined of the three worlds, it’s essentially

now a less politically correct way of referring to what economists now call the

developing world.

The

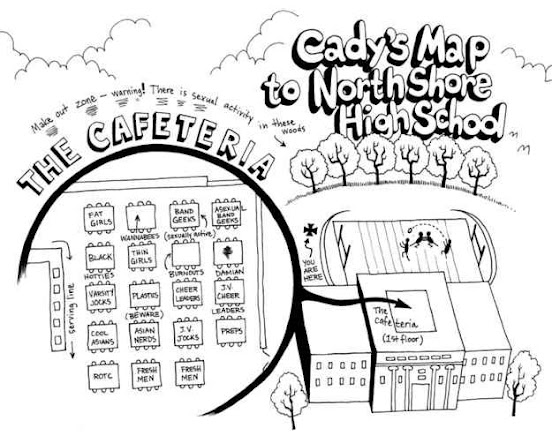

multi-polar school in Mean Girls (2004)

lacked a NAM

The discipline of behavioralism is not as fashionable as once it was but its tools and methods remain in use in fields as diverse (or similar according to some) as political science, marketing, crowd control and zoology, much of the work exploring group dynamics, both internally and the interactions between factions. Although it wasn’t intended to be taken too seriously, one structuralist did make the point that the sheer number of cliques (20-odd) in the Mean Girls high school meant it was unlikely a “non-aligned” grouping would emerge because the extent of the multi-polarity was such that the concept made no sense; even in the dynamic system of ever-shifting alliances between small numbers of cliques, in a sense all simultaneously were non-aligned with the majority of others.