Exordium (pronounced ig-zawr-dee-uhm

or ik-sawr-dee-uhm)

(1) The beginning of anything.

(2) The introductory part of an oration, treatise etc.

(3) In formal rhetoric, the introductory section of a

discourse in Western classical rhetoric.

(4) In legal drafting (probate), as an exordium clause,

the first paragraph or sentence in a will and testament

1525–1535: From the Latin exōrdium (beginning, commencement), from exōrdīrī (I begin, commence) the construct being ex- (out of; from) + ōrd(īrī)

(to begin) + -ium. The

ex- prefix was from the Middle English, from words borrowed from the Middle

French, from the Latin ex (out of,

from), from the primitive Indo-European eǵ- & eǵs-

(out). It was cognate with the Ancient

Greek ἐξ (ex) (out of, from), the Transalpine

Gaulish ex- (out), the Old Irish ess- (out), the Old Church Slavonic изъ

(izŭ) (out) & the Russian из (iz) (from, out of). The “x” in “ex-“, sometimes is elided before

certain constants, reduced to e- (eg ejaculate). The –ium

suffix (used most often to form adjectives) was applied as (1) a nominal suffix

(2) a substantivisation of its neuter forms and (3) as an adjectival

suffix. It was associated with the

formation of abstract nouns, sometimes denoting offices and groups, a

linguistic practice which has long fallen from fashion. In the New Latin, it was the standard suffix

appended when forming names for chemical elements. Exordium and exord are

nouns, exordior is a verb, exordial is an adjective; the noun plural is

exordiums or exordia, the choice dictated by consistency of use within a document,

either the Latin or English being used in all cases where both exist.

The original meaning of the Latin exōrdium was “the warp laid on a loom before the web is begun” which entered general use as “starting point” and used liberally of physical objects, processes or abstractions. The term came to assume a specific technical meaning when it was applied to the first of the traditional divisions of a speech established by classical rhetoricians, this later extended to many forms of literature to describe introductions, especially the opening section of a discourse or composition. In English law, this was formalized in the law of probate as the exordium clause in wills, an opening statement of (more or less) standardized facts. In English, there are many words used to convey the same meaning including introduction, forward, preamble, abstract, (executive) summary, preface, prologue, preliminary, prelude, opening, presentation, proposition, signal, overture, preliminary, prolegomenon, prelusion & proem. However, although English is notorious for accumulating synonyms (often with other or overlapping meanings), the language is not unique in that, the synonyms of the Latin verb exōrdior (I begin) (present infinitive exōrdīrī, perfect active exōrsus sum) including incohō, occipiō, incipiō, coepiō, ōrdior, initiō, ineō, moveō & mōlior.

The exordium clause

In common law jurisdictions a will need not contain an

exordium clause, indeed, an English court once held to be valid a will which consisted

of the words “All to mum” scratched on the paint of the overturned tractor which

would crush to death the writer. It was a

document of interest too because the judge ruled the “mum” referred not to the

deceased’s mother (as would be the prima

facie assumption under the usual principles of interpretation) but instead his wife, the decision

based on evidence of the man’s use of the term.

It’s said to be the shortest legitimate will in the English language although

a Czech court trumped it for brevity by accepting the linguistically unambiguous

Vše ženě (everything to wife)

scrawled on a bedroom wall. One might be tempted to ponder the circumstances in which that transpired.

Extract from Adolf Hitler’s last will & testament (with English translation, held by US National Archives).

Adolf Hitler’s (1889-1945; German head of government

1933-1945 & head of state 1934-1945) will contained an exordium which was

unlike the prosaic list of facts familiar in English law but, in the

circumstances prevailing in the Führerbunker on 29 April 1945, it was probably

thought redundant to bother with things like name, address or an assertion of

one’s soundness of mind although he did mention his upcoming marriage, though

without naming the lucky woman.

As I did not consider that I

could take responsibility, during the years of struggle, of contracting a

marriage, I have now decided, before the closing of my earthly career, to take

as my wife that girl who, after many years of faithful friendship, entered, of

her own free will, the practically besieged town in order to share her destiny

with me. At her own desire she goes as my wife with me into death. It will

compensate us for what we both lost through my work in the service of my

people.

He went on to the brief business of what he was leaving

to his beneficiaries:

What I possess belongs - in

so far as it has any value - to the Party. Should this no longer exist, to the

State; should the State also be destroyed, no further decision of mine is

necessary. My pictures, in the

collections which I have bought in the course of years, have never been

collected for private purposes, but only for the extension of a gallery in my

home town of Linz on Donau. It is my

most sincere wish that this bequest may be duly executed.

I nominate as my Executor my

most faithful Party comrade, Martin Bormann.

He is given full legal authority to make all decisions. He is permitted

to take out everything that has a sentimental value or is necessary for the

maintenance of a modest simple life, for my brothers and sisters, also above

all for the mother of my wife and my faithful co-workers who are well known to

him, principally my old Secretaries Frau Winter etc. who

have for many years aided me by their work.

Saving others the trouble, he thoughtfully then made the

funeral and cremation arrangements.

I myself and my wife - in

order to escape the disgrace of deposition or capitulation - choose death. It

is our wish to be burnt immediately on the spot where I have carried out the

greatest part of my daily work in the course of a twelve years' service to my

people.

Page 1 of Adolf Hitler’s political testament.

As a will, Hitler’s document was valid at the time of its execution and remained so even after the dissolution German state. Hitler’s sister Paula (1896-1960) attempted in 1952 to enforce the will in a FRG (Federal Republic of Germany, the old West Germany) court but was denied on the technical grounds that he’d not yet been declared legally dead and it wasn’t until 1960, some six months after her death, that a Federal Court in Berchtesgaden awarded her a portion of the estate. The companion document, Hitler’s political testament, has bothered legal theorists and political scientists ever since. Arbitrarily, Hitler reverted to the constitutional model to that which had last existed in 1934, splitting the roles of head of state (president) and government (chancellor), appointing two different people although the title of Führer remained unique to him. He also named a new cabinet (although not all of these offices were so-filled) and the consensus among historians is that in the circumstances of the time and given the nature of the führerstaat (the leadership practices and principles in the Nazi state), the appointments were lawful between Hitler’s death and the dissolution of the German state on 8 May 1945. It was thus a continuation of the existing entity, not a "Fourth Reich" as the last few weeks are sometimes called and certainly, there was after the dissolution no legal basis for the so-call “cabinet” which continued to meet until the members were arrested on 23 May 1945.

Jane Austen’s (1775–1817) last will & testament.

However it’s recommended a will include an exordium

clause in something like its standard form though it need not be described as

such and what the clause does is list the document’s key elements including (1)

the name of the person making the will (including any other names by which they

may then or in the past have been known), (2) the person’s normal place of

residence (expressed in full including street or flat numbers, the locality and

province etc), (3) a declaration revoking any earlier wills and (4) a

declaration the document is the will belonging to the named person. The historical practice (still often seen in

fiction) of (5) including a phrase like “being sound of mind and body” seems now

used with less frequency but some still feature this. In long or complex wills, all other matters

may be handled in other clauses but if the matters are simple, (6) beneficiaries

can be included in the exordium clause, as can (7) any other parties who may in

some way be involved including issues dealing with the guardianship of minors.

What an exordium clause thus does is set out basic facts

and it’s important they are written in such a way that there can be no misinterpretation

or ambiguity, beneficiaries for example identified where necessary with some

collateral information such as a date of birth or some other information unique

to them. A well-written exordium clause

can ensure there can be no contesting of a will on the basis of factual error

and seeking legal advice is recommended, even Warren Burger (1907–1995 US Chief

Justice 1969-1986) causing his executor problems because the

judge was a bit sloppy in his drafting.

A model example might be:

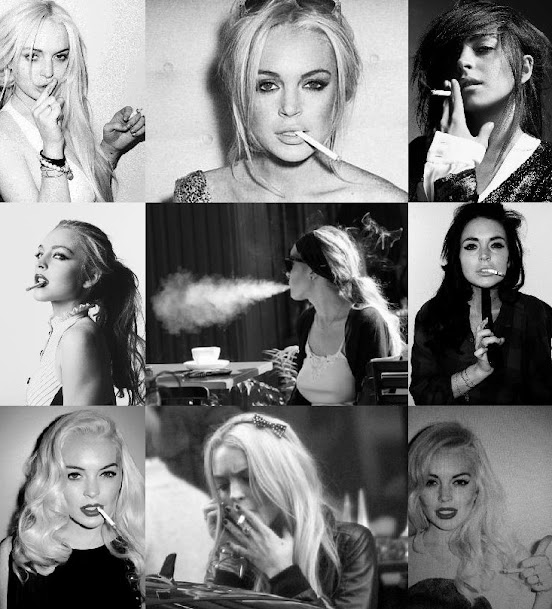

I, Lindsay Dee Lohan, born July 2, 1986, residing at 10585

Santa Monica Boulevard, Los Angeles, California 90025, being sound of mind and body, declare

this to be my will and I revoke any and all wills and codicils previously made.

Although not allowed in all jurisdictions, the exordium clause can work in conjunction with other clauses including (1) the residuary clause which deals with any assets which remain after the specifics of the will have been executed, (2) the in terrorem (in fear) clause which states that should a beneficiary challenge the will, they will be denied any benefits of that will, (3) the testamentary trust clause which, for various purposes, passes the estate into a trust prior to any distribution of assets and (4) a no-contest clause, a variation of the in terrorem clause in that it denies benefits to any beneficiary who challenges the will and loses, the purpose being to discourage vexatious actions or those with no prospect of success.