Flat (pronounced flat)

(1) Level, even, or without unevenness of surface, as land or tabletops.

(2) Having a shape or appearance not deep or thick.

(3) Deflated; collapsed.

(4) Absolute, downright, or positive; without qualification; without modification or variation.

(5) Without vitality or animation; lifeless; dull.

(6) Prosaic, banal, or insipid.

(7) In artistic criticism, lifeless, not having the illusion of volume or depth or lacking contrast or gradations of tone or colour.

(8) Of paint, without gloss; not shiny; matt.

(9) In musical criticism, not clear, sharp, or ringing, as sound or a voice lacking resonance and variation in pitch; monotonous.

(10) In musical notation, the character ♭ which, when attached to a note or a staff degree, lowers its significance one chromatic half step.

(11) In music, below an intended pitch, as a note; too low (as opposed to sharp).

(12) In English grammar, derived without change in form, as to brush from the noun brush and adverbs that do not add -ly to the adjectival form as fast, cheap, and slow.

(13) In nautical matters, a sail cut with little or no fullness.

(14) A woman’s shoe with a flat heel (pump) or no heel (ballet flat).

(15) In geography, a marsh, shoal, or shallow.

(16) In shipbuilding, a partial deck between two full decks (also called platform).

(17) In construction, broad, flat piece of iron or steel for overlapping and joining two plates at their edges.

(18) In architecture, a straight timber in a frame or other assembly of generally curved timbers.

(19) An iron or steel bar of rectangular cross section.

(20) In textile production, one of a series of laths covered with card clothing, used in conjunction with the cylinder in carding.

(21) In photography, one or more negatives or positives in position to be reproduced.

(22) In printing, a device for holding a negative or positive flat for reproduction by photoengraving.

(23) In horticulture, a shallow, lidless box or tray used for rooting seeds and cuttings and for growing young plants.

(24) In certain forms of football, the area of the field immediately inside of or outside an offensive end, close behind or at the line of scrimmage.

(25) In horse racing, events held on flat tracks (ie without jumps).

(26) An alternative name for a residential apartment or unit (mostly UK, Australia, NZ).

(27) In phonetics, the vowel sound of a as in the usual US or southern British pronunciation of hand, cat, usually represented by the symbol (æ).

(28) In internal combustion engines (ICE), a configuration in which the cylinders are horizontally opposed.

1275–1325: From the Middle English flat from the Old Norse flatr, related to Old High German flaz (flat) and the Old Saxon flat (flat; shallow) and akin to Old English flet. It was cognate with the Norwegian and Swedish flat and the Danish flad, both from the Proto-Germanic flataz, from Proto-Indo-European pleth (flat); akin to the Saterland Frisian flot (smooth), the German flöz (a geological layer), the Latvian plats and Sanskrit प्रथस् (prathas) (extension). Source is thought to be the Ancient Greek πλατύς (platús & platys) (flat, broad). The sense of "prosaic or dull" emerged in the 1570s and was first applied to drink from circa 1600, a meaning extended to musical notes in the 1590s (ie the tone is "lowered"). Flat-out, an adjectival form, was first noted in 1932, apparently a reference to pushing a car’s throttle (accelerator) flat to the floor and thus came to be slang for a vehicle’s top speed. The US colloquial use as a noun from 1870 meaning "total failure" endures in the sense of “falling flat”. The notion of a small, residential space, a divided part of a larger structure, dates from 1795–1805; variant of the obsolete Old English flet (floor, house, hall), most suggesting the meaning followed the early practice of sub-dividing buildings within levels. In this sense, the Old High German flezzi (floor) has been noted and it is perhaps derived from the primitive Indo-European plat (to spread) but the link to flat as part of a building is tenuous.

The installation’s other pieces are Compressions cubiques (Cubed compressions), made from the salvaged wrecks of cars of various makes (Simca, Renault, Fiat etc) in what are presumably “designer colors”, the artist’s thing being depictions of shapes (including the human form, in whole or in part) in materials like scrap metal and plastics. The symbolism was apparently something about the movement’s usual suspects (consumerism, alienation and the wastefulness of capitalist mass-production). Baldaccini was leading light in the Nouveau Réalisme (“new wave of realism) movement (post-war Europe was a place of political and artistic “movements”) and he’s now best remembered for his many “compression” pieces, most of which were cars which had emerged from the crusher. It had been the sight of a hydraulic crushing machine at a scrap yard which had inspired the artist and the pieces became his signature, rather as “wrapping” large structures was for Christo (Christo Javacheff (1935–2020)). The pair encapsulated modern art: Christo wrapped a building and called it “art”, while Baldaccini took a crushed car, put it in a gallery and called it “art”. Prior to some point in the twentieth century, such antics would have been implausible but after things moved from the critical relationship being between artist and audiences to that between artist and critics, just about anything became possible, thus all those post-war “movements”. A footnote in Baldaccini's life is that in 1959 he became the second owner of Brigitte Bardot's (1921–1998) 1954 Simca 9 Weekend Cabriolet. Whether he bought it or it was a gift isn't clear but it was a genuine one-off, the aluminum and steel body hand made by the coachbuilder Facel (soon to become famous for the memorable Facel Vegas) and, appropriately, carries serial number 001. It still exists and is on permanent display at the Lane Motor Museum in Nashville, Tennessee. Lane specializes in European cars (with a commendable emphasis on the rare, strange and truly bizarre) and, like most of its exhibits, the Simca remains in sound working order; it is, in the jargon of the collector trade, “a survivor”, being wholly original and never having been restored. .

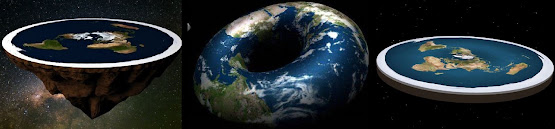

The Flat Earth

Members of the Flat

Earth Society believe the Earth is flat but there's genuine debate within the organisation, some holding the shape is disk-like,

others that it's conical but both agree we live on something like the face of a

coin. There are also those in a radical faction suggesting it's actually shaped like a doughnut but this theory is regarded

by the flat-earth mainstream as speculative or even "heretical". Evidence, such as photographs from orbit showing Earth to be a sphere, is dismissed as part of the "round Earth conspiracy" run by NASA and others.

The flat-earther theory is that the Arctic Circle is in the center and the Antarctic is a 150-foot (45m) tall wall of ice around the rim; NASA contractors guard the ice wall so nobody can fall over the edge. Earth's daily cycle is a product of the sun and moon being 32 mile (51 km) wide spheres travelling in a plane 3,000 miles (4,800 km) above Earth. The more distant stars are some 3100 miles (5000 km) away and there's also an invisible "anti-moon" which obscures the moon during lunar eclipses.

Lindsay Lohan in Lanvin Classic Garnet ballet flats (Lanvin part-number is FW-BAPBS1-NAPA-A18391), Los Angeles, 2012. In some markets, these are known as ballet pumps.

Flat Engines

“Flat” engines are so named because the cylinders are horizontally opposed which means traditionally (though not inherently) there are an equal number of cylinders. It would not be impossible to build a flat engine with an uneven cylinder count but the disadvantages would probably outweigh anything gained and specific efficiencies could anyway be obtained in more conventional ways. The flat engine configuration can be visualized as a “flattened V” and this concept does have some currency because engineers like to distinguish between the “boxer” and the “180o V” (also called the “horizontal V”, both forms proving engineers accord the rules of math more respect than those of English). The boxer is fitted with one crankpin per cylinder while the 180o V uses one crankpin per pair of horizontally opposed cylinders.

The 180o Vee vs the Boxer.

The

boxer layout has been in use since 1897 when Carl (also as Karl) Benz

(1844–1929) released a twin cylinder version and it was widely emulated

although Mercedes-Benz has never returned to the idea while others (notably BMW

(motorcycles), Porsche and Subaru) have made variations of the flat configuration

a signature feature. The advantages of

the flat form include (1) a lower centre of gravity, (2) reduced long-term wear

on the cylinder walls because some oil tends to remain on the surface when not

running, meaning instant lubrication upon start-up and (3) reduced height meaning the physical

mass sits lower, permitting bodywork more easily to be optimized for aerodynamic

efficiency although this can't be pursued to extremes on road cars because there are various rules about the minimum heights of this & that. The disadvantages include (1)

greater width, (2) accessibility (a cross-flow combustion chamber will

necessitate the intake or exhaust (usually the latter) plumbing being on the

underside, (3) some challenges in providing cooling and (4) the additional weight

and complexity (two cylinder heads) compare to an in-line engine (although the

same can be said of conventional vees).

Flat out but anti-climatic: The Coventry-Climax flat-16

Flat engines have ranged from the modest (the flat-4 in the long-running Volkswagen Beetle (1939-2003)) to the spectacular (Coventry-Climax and Porsche both building flat-16s although both proved abortive). The most glorious failure however was the remarkable BRM H16, used to contest the 1966-1967 Formula One (F1) season when the displacement limit was doubled to three litres. What BRM did was take the 1.5 litre V8 with which they’d won the 1962 F1 driver and constructor championships, flatten it to and 180o V and join two as a pair, one atop the other. It was a variation on what Coventry-Climax had done with their 1.5 litre V8 which they flattened and joined to create a conventional flat-16 and the two approaches illustrate the trade-offs which engineers have to assess for merit. BRM gained a short engine but it was tall which adversely affected the centre of gravity while Coventry-Climax retained a low profile but had to accommodate great length and challenges in cooling. The Coventry-Climax flat-16 never appeared on the track and the BRM H16 was abandoned although it did win one Grand Prix (albeit when installed in a Lotus chassis). Unfortunately for those who adore intricacy for its own sake, BRM's plan to build four valve heads never came to fruition so the chance to assess an engine with sixteen cylinders, two crankshafts, eight camshafts, two distributers and 64 valves was never possible. Truly, that would have been compounding existing errors on a grand scale. Tellingly perhaps, the F1 titles in 1966-1967 were won using an engine based on one used in the early 1960s by General Motors in road cars (usually in a mild state of tune although there was an unsuccessful foray into turbo-charging) before it was abandoned and sold to Rover to become their long-running aluminium V8. As raced, it boasted 8 cylinders, one crankshaft, two camshafts, one distributer and 16 valves. The principle of Occam's Razor (the reductionist philosophic position attributed to English Franciscan friar & theologian William of Ockham (circa 1288–1347) written usually as Entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem (entities must not be multiplied beyond necessity) is essentially: “the simplest solution is usually the best".

The ultimate flats: Napier-Sabre H-24 (left) and BRM H-16 (right).

The H configuration though was sound if one had an appropriate purpose of its application. What showed every sign of evolving into the most outstanding piston aero-engine of World War II (1939-1945) was the Napier-Sabre H-24 which, with reduced displacement, offered superior power, higher engine speeds and reduced fuel consumption compared with the conventional V12s in use and V16s in development. The early teething troubles had been overcome and extraordinary power outputs were being obtained in testing but the arrival of the jet age meant the big piston-engined warplanes were relics and development of the H24 was abandoned along with the H-32 planned for use in long-range heavy bombers.

A mastectomy bra with prostheses (left) and with the prostheses inserted in the cups' pockets (centre & right).

For those who elect not to have a reconstruction after the loss of a breast, there are bras with “double-skinned” cups which feature internal “pockets” into which a prosthetic breast form (a prosthesis) can be inserted. Those who have had a unilateral mastectomy (the surgical removal of one breast) can choose a cup size to match the remaining while those who lost both (a bilateral or double mastectomy) can adopt whatever size they prefer. There are now even single cup bras for those who have lost one breast but opt not to use a prosthetic, an approach which reflects both an aesthetic choice and a reaction against what is described in the US as the “medical-industrial complex”, the point being that women who have undergone a mastectomy should not be subject to pressure either to use a prosthetic or agree to surgical reconstruction (a lucrative procedure for the medical industry). This has now emerged as a form of advocacy called the “going flat” movement which has a focus not only on available fashions but also the need for a protocol under which, if women request an AFC (aesthetic flat closure, a surgical closure (sewing up) in which the “surplus” skin often preserved to accommodate a future reconstructive procedure is removed and the chest rendered essentially “flat”), that is what must be provided. The medical industry has argued the AFC can preclude a satisfactory cosmetic outcome in reconstruction if a woman “changes her mind” but the movement insists it's an example of how the “informed consent” of women is not being respected. Essentially, what the “going flat” movement (the members style themselves as "flatties") seems to be arguing is the request for an AFC should be understood as an example of the legal principle of VAR (voluntary assumption of risk). The attitude of surgeons who decline to perform an AFC is described by the movement as the “flat refusal”.