Demand (pronounced dih-mand (U) or dee–mahnd (non-U))

(1) To ask for with proper authority; claim as a right.

(2) To ask for peremptorily or urgently.

(3) To call for or require as just, proper, or necessary.

(4) In law, to lay formal claim to.

(5) In law, to summon, as to court.

(6) An urgent or pressing requirement.

(7) In economics, the desire to purchase, coupled (hopefully) with the power to do so.

(8) In economics, the quantity of goods that buyers will take at a particular price.

(9) A requisition; a legal claim.

(10) A question or inquiry (archaic).

1250-1300: From Middle English demaunden and Anglo-French demaunder, derived from the Medieval Latin dēmandāre (to demand, later to entrust) equivalent to dē + mandāre (to commission, order). The Old French was demander and, like the English, meant “to request” whereas "to ask for as a right" emerged in the early fifteenth century from Anglo-French legal use. As used in economic theory and political economy (correlating to supply), first attested from 1776 in the writings of Adam Smith. The word demand as used by economists is a neutral term which references only the conjunction of (1) a consumer's desire to purchase goods or services and (2) hopefully the power to do so. However, in general use, to say that someone is "demanding" something does carry a connotation of anger, aggression or impatience. For this reason, during the 1970s, the language of those advocating the rights of women to secure safe, lawful abortion services changed from "abortion on demand" (ie the word used as an economist might) to "pro choice". Technical fields (notably economics) coin derived forms as they're required (counterdemand, overdemand, predemand etc). Demand is a noun & verb, demanding is a verb & adjective, demandable is an adjective, demanded is a verb and demander is a noun; the noun plural is demands.

Video on Demand (VoD)

Directed by Tiago Mesquita with a screenplay by Mark Morgan, Among the Shadows is a thriller which straddles the genres, elements of horror and the supernatural spliced in as required. Although in production since 2015, with the shooting in London and Rome not completed until the next year, it wasn’t until 2018 when, at the European Film Market, held in conjunction with the Internationale Filmfestspiele Berli (Berlin International Film Festival), that Tombstone Distribution listed it, the distribution rights acquired by VMI, Momentum and Entertainment One, and VMI Worldwide. In 2019, it was released progressively on DVD and video on demand (VoD), firstly in European markets, the UK release delayed until mid-2020. In some markets, for reasons unknown, it was released with the title The Shadow Within.

Video on Demand (VoD) and streaming services are similar concepts in video content distribution but there are differences. VoD is a system which permits users to view content at any time, these days mostly through a device connected to the internet across IP (Internet Protocol), the selection made from a catalog or library of available titles and despite some occasionally ambiguous messaging in the advertising, the content is held on centralized servers and users can choose directly to stream or download. The VoD services is now often a sub-set of what a platform offers which includes content which may be rented, purchased or accessed through a subscription.

Streaming is a method of delivering media content in a continuous flow over IP and is very much the product of the fast connections of the twenty-first century. Packets are transmitted in real-time which enables users to start watching or listening without waiting for an entire file (or file set) to download, the attraction actually being it obviates the need for local storage. There’s obviously definitional and functional overlap and while VoD can involve streaming, not all streaming services are technically VoD and streaming can also be used for live events, real-time broadcasts, or continuous playback of media without specific on-demand access. By contrast, the core purpose of VoD is to provide access at any time and streaming is a delivery mechanism, VoD a broad concept and streaming a specific method of real-time delivery as suited to live events as stored content.

The Mercedes-Benz SSKL and the Demand Supercharger

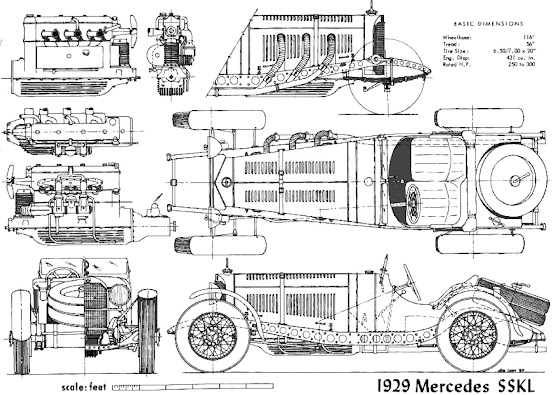

Modern rendition of Mercedes-Benz SSLK in schematic, illustrating the drilled-out chassis rails. The title is misleading because the four or five SSKLs built were all commissioned in 1931 (although it's possible one or more used a modified chassis which had been constructed in 1929). All SSK chassis were built between 1928-1932 although the model remained in the factory's catalogue until 1933.

The Mercedes-Benz SSKL was one of the last of the road cars which could win top-line grand prix races. An evolution of the earlier S, SS and SSK, the SSKL (Super Sports Kurz (short) Leicht (light)) was notable for the extensive drilling of its chassis frame to the point where it was compared to Swiss cheese; reducing weight with no loss of strength. The SSKs and SSKLs were famous also for the banshee howl from the engine when the supercharger was running; nothing like it would be heard until the wail of the BRM V16s twenty years later. It was called a demand supercharger because, unlike some constantly-engaged forms of forced-induction, it ran only on-demand, in the upper gears, high in the rev-range, when the throttle was pushed wide-open. Although it could safely be used for barely a minute at a time, when running, engine power jumped from 240-odd horsepower (HP) to over 300. The number of SSKLs built has been debated and the factory's records are incomplete because (1) like many competition departments, it produced and modified machines "as required" and wasn't much concerned about documenting the changes and (2) many archives were lost as a result of bomb damage during World War II (1939-1945); most historians suggest there were four or five SSKLs, all completed (or modified from earlier builds) in 1931. The SSK had enjoyed great success in competition but even in its heyday was in some ways antiquated and although powerful, was very heavy, thus the expedient of the chassis-drilling intended to make it competitive for another season. Lighter (which didn't solve but at least to a degree ameliorated the brake & tyre wear) and easier to handle than the SSK (although the higher speed brought its own problems, notably in braking), the SSKL enjoyed a long Indian summer and even on tighter circuits where its bulk meant it could be out-manoeuvred, sometimes it still prevailed by virtue of durability and sheer power.

Rudolf Caracciola (1901–1959) and SSKL in the wet, German Grand Prix, Nürburgring, 19 July, 1931. Alfred Neubauer (1891–1980; racing manager of the Mercedes-Benz competition department 1926-1955) maintained Caracciola "...never really learned to drive but just felt it, the talent coming to him instinctively."

Sometimes too it got lucky. When the field assembled in 1931 for the Fünfter Großer Preis von Deutschland (fifth German Grand Prix) at the Nürburgring, even the factory acknowledged that at 1600 kg (3525 lb), the SSKLs, whatever their advantage in horsepower, stood little chance against the nimble Italian and French machines which weighed-in at some 200 KG (440 lb) less. However, on the day there was heavy rain with most of race conducted on a soaked track and the twitchy Alfa Romeos, Maseratis and the especially skittery Bugattis proved less suited to the slippery surface than the truck-like but stable SSKL, the lead built up in the rain enough to secure victory even though the margin narrowed as the surface dried and a visible racing-line emerged. Time and the competition had definitely caught up by 1932 however and it was no longer possible further to lighten the chassis or increase power so aerodynamics specialist Baron Reinhard von Koenig-Fachsenfeld (1899-1992) was called upon to design a streamlined body, the lines influenced both by his World War I (1914-1918 and then usually called the "World War") aeronautical experience and the "streamlined" racing cars which had been seen in the previous decade. At the time, the country greatly was affected by economic depression which spread around the world after the 1929 Wall Street crash, compelling Mercedes-Benz to suspend the operations of its competitions department so the one-off "streamliner" was a private effort (though with some tacit factory assistance) financed by the driver (who borrowed some of the money from his mechanic!).

The driver was Manfred von Brauchitsch (1905-2003), nephew of Major General (later Generalfeldmarschall (Field Marshal)) Walther von Brauchitsch (1881–1948; Oberbefehlshaber (Commander-in-Chief) of OKH (Oberkommando des Heeres (the German army's high command) 1938-1941). An imposing but ineffectual head of the army, Uncle Walther also borrowed money although rather more than loaned by his nephew's mechanic, the field marshal's funds coming from the state exchequer, "advanced" to him by Adolf Hitler (1889-1945; Führer (leader) and German head of government 1933-1945 & head of state 1934-1945). Quickly Hitler learned the easy way of keeping his mostly aristocratic generals compliant was to loan them money, give them promotions, adorn them with medals and grant them estates in the lands he'd stolen during his many invasions. His "loans" proved good investments. Beyond his exploits on the circuits, Manfred von Brauchitsch's other footnote in the history of the Third Reich (1933-1945) is the letter sent on April Fools' Day 1936 to Uncle Walther (apparently as a courtesy between gentlemen) by Baldur von Schirach (1907-1974; head of the Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth) 1931-1940 & Gauleiter (district party leader) and Reichsstatthalter (Governor) of Vienna 1940-1945) claiming he given a "horse whipping" to the general's nephew because a remark the racing driver was alleged to have made about Frau von Schirach (the daughter of Hitler's court photographer!). It does seem von Schirach did just that though it wasn't quite the honorable combat he'd claimed: in the usual Nazi manner he'd arrived at von Brauchitsch's apartment in the company of several thugs and, thus assisted, swung his leather whip. Von Brauchitsch denied ever making the remarks. Unlike the German treasury, the mechanic got his money back and that loan proved a good investment, coaxing from the SSKL a victory in its final fling. Crafted in aluminum by Vetter in Cannstatt, the body was mounted on von Brauchitsch's race-car and proved its worth at the at the Avusrennen (Avus race) in May 1932; with drag reduced by a quarter, the top speed increased by some 12 mph (20 km/h) and the SSKL won its last major trophy on the unique circuit which rewarded straight-line speed like no other. It was the last of the breed; subsequent grand prix cars would be pure racing machines with none of the compromises demanded for road-use.

Evolution of the front-engined Mercedes-Benz grand prix car, 1928-1954

The size of the S & SS was exaggerated by the unrelieved expanses of white paint (Germany's designated racing color) although despite what is sometimes claimed, Ettore Bugatti’s (1881–1947) famous quip “fastest trucks in the world” was his back-handed compliment not to the German cars but to W. O. Bentley’s (1888–1971) eponymous racers which he judged brutish compared to his svelte machines. Die Gurke ended up silver only because such had been the rush to complete the build in time for the race, there was time to apply the white paint so it raced in a raw aluminum skin. Remarkably, in full-race configuration, die Gurke was driven to Avus on public roads, a practice which in many places was tolerated as late as the 1960s. Its job at Avus done, die Gurke was re-purposed for high-speed tyre testing (its attributes (robust, heavy and fast) ideal for the purpose) before "disappearing" during World War II. Whether it was broken up for parts or metal re-cycling, spirted away somewhere or destroyed in a bombing raid, nobody knows although it's not impossible conventional bodywork at some point replaced the streamlined panels. In 2019, Mercedes-Benz unveiled what it described as an "exact replica" of die Gurke, built on an original (1931) chassis.