Rimbellisher (pronounced rhim-bell-lysh)

A

decorative ring attached to the rim of a car's wheel.

1940s:

A portmanteau word, the construct being rim + (em)bellish +-er and originally a trademarked

brand of the Ace company. Rim was from the tenth century Middle

English rim, rym & rime, from the Old English rima (rim, edge, border, bank, coast),

from the Proto-Germanic rimô & rembô (edge, border), from the primitive

Indo-European rem- & remə- (to rest, support, be based). It was cognate with the Saterland Frisian Rim (plank, wooden cross, trellis), the Old

Saxon rimi (edge; border; trim) and

the Old Norse rimi (raised strip of

land, ridge). Rim generally means “an edge

around something, especially when circular” and is used in fields a different

as engineering and vulcanology. The use

in political geography is an extension of the idea, something like “PacRim”

(Pac(ific) + rim) used to group the nations with coastlines along the Pacific

Ocean. The use in print journalism

referred to “a semicircular copydesk”. The special use in metallurgy described the outer

layer of metal in an ingot where the composition was different from that of the

centre. The word rim is an especially

frustrating one for golfers to hear because it describes the ball rolling

around the rim of the hole but declining to go in.

Embellish

dates from the early fourteenth century and was from the Middle English embelisshen from the Anglo-French, from

the Middle French embeliss- (stem of embelir), the construct being em- (The form taken by en- before the

labial consonants “b” & “p”, as it assimilates place of articulation). The en- prefix was from the Middle English en- & in-. In the Old French it

existed as en- & an-, from the Latin in- (in, into); it was also from an alteration of in-, from the Middle English in-, from the Old English in- (in, into), from the Proto-Germanic in (in).

Both the Latin and Germanic forms were from the primitive Indo-European en (in, into) and the frequency of use

in the Old French is because of the confluence with the Frankish an- intensive prefix, related to the Old

English on-.) + bel-, from the Latin bellus

(pretty) + -ish. The –ish suffix was from the Middle English –ish & -isch, from the Old English –isċ,

from the Proto-West Germanic -isk,

from the Proto-Germanic –iskaz, from

the primitive Indo-European -iskos. It was cognate with the Dutch -s; the German -isch (from which Dutch gained -isch),

the Norwegian, Danish, and Swedish -isk

& -sk, the Lithuanian –iškas, the Russian -ский (-skij) and the Ancient Greek diminutive

suffix -ίσκος (-ískos); a doublet of

-esque and -ski. There exists a welter

of synonyms and companion phrases such as decorate, grace, prettify, bedeck,

dress up, exaggerate, gild, overstate, festoon, embroider, adorn, spiff up,

trim, magnify, deck, color, enrich, elaborate, ornament, beautify, enhance,

array & garnish. Embellish is a

verb, embellishing is a noun & verb, embellished is a verb & adjective

and embellisher & embellishment are nouns; the noun plural is

embellishments.

The –er suffix was from the Middle English –er & -ere, from the Old English -ere,

from the Proto-Germanic -ārijaz,

thought most likely to have been borrowed from the Latin –ārius where, as a suffix, it was used to form adjectives from nouns

or numerals. In English, the –er suffix,

when added to a verb, created an agent noun: the person or thing that doing the

action indicated by the root verb. The

use in English was reinforced by the synonymous but unrelated Old French –or & -eor (the Anglo-Norman variant -our),

from the Latin -ātor & -tor, from the primitive Indo-European -tōr.

When appended to a noun, it created the noun denoting an occupation or

describing the person whose occupation is the noun. Rimbellisher

is a noun and the noun plural is rimbellishers.

All other forms are non-standard but a wheel to which a rimbellisher has

been fitted could be said to be rimbellished (adjective) white the person doing

the fitting would be a rimbellisher (noun), the process an act of rimbellishing

(verb) and the result a rimbellishment (noun).

Jaguar XK120 with wire wheels (left), with hubcaps (centre) and with hubcaps and rimbellishers (right).

The

Jaguar XK range (1948-1961) was available either with solid or wire wheels and

while the choice was usually on aesthetic grounds, those using the things in

competition sometimes had to assess the trade-offs. The wire wheels were lighter and provided

better cooling of the brakes (especially those connected to the rear wheels

which were covered with fender skirts (spats) when the steel wheels were

fitted. In many forms of motor sport

that was of course a great advantage but the spokes and the deletion of the

skirts came at an aerodynamic cost, the additional drag induced by the combination

reducing top speed by a up to 5 mph (8 km/h) and increasing fuel

consumption. It was thus a question of

working out what was most valued and in the early days, where regulations

permitted, some drivers used wire-wheels at the front and retained the skirts

at the rear, attempting to get as much as possible of the best of both

worlds (the protrusion of the hubs used

on the wire wheels precluded them from fitting behind the skirts). Jaguar XK owners would never refer to their

wheels as “rims” although there may be some who have added “rims” to their

modern (post Tata ownership) Jaguars.

Hofit Golan (b 1985) and Lindsay Lohan (b 1986) attending Summer Tour Maserati in Porto Cervo, Sardinia, July 2016. The Maserati Quattroporte is a 1964 Series I, fitted with steel wheels and rimbellishers.

Among certain classes, it’s now common to refer to wheels as rims, and the flashier the product, the more likely it is to be called a “rim”. Good taste is of course subjective but as a general rule, the greater the propensity to being described as a rim, the more likely it is to be something in poor taste. That’s unless it actually is a rim, some wheels being of multi-part construction where the rim is a separate piece (and composed sometimes from a different metal). In the early days of motoring this was the almost universal method of construction and it persisted in trucks until relatively recently (although still used in heavy, earth-moving equipment and such). However, those dealing with the high-priced, multi-pieced wheels seem still to call them wheels and use the term “rim” only when discussing the actual rim component.

1937 Rolls-Royce Phantom III four-door cabriolet with coachwork by German house Voll Ruhrbeck, fitted with the standard factory wire wheels (left) and 1937 Rolls-Royce Phantom III fixed head coupé (FHC) with coachwork by Belgium house Vesters et Neirinck, fitted with the “Ace Deluxe” wheel discs which fitted over the standard factory wire wheels (right). The coupé, fabricated in Brussels, was unusual in pre-war coachbuilding in that there was no B-pillar, the style which would become popular in the US between the 1950s-1970s where in two & four-door form it would be described as a “hardtop”, the nomenclature which would over the years be sometimes confused with the “hard-tops” sometime supplied with convertibles as a more secure alternative to the usual “soft top”.

According

to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), the first known instance of rimbellisher

in print was in The Motor (1903-1988) magazine in 1949 although they seem first to have been so-described when on

sale in England in 1948. The

rimbellishers were a new product for the Ace Company which in the 1930s had

specialized in producing disk-like covers for wire-wheels. That might seem strange because wire wheels

are now much admired but in the 1930s many regarded them as old-fashioned

although their light-weight construction meant they were often still used. What Ace’s aluminium covers provided was the

advantage of the lighter weight combined with a shiny, modernist look and they

were also easy to keep clean, unlike wire wheels which could demand hours each

month to maintain.

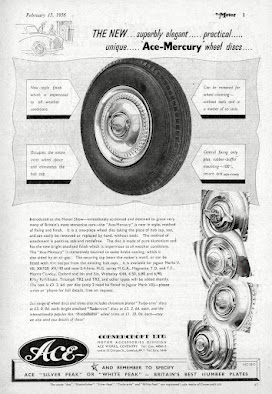

The Ace company's publicity material from the 1950s.

In

the post-war years the rimbellishers became popular because they were a

detail which added a “finished” look.

They were a chromed ring which attached inside the rim of the wheel, providing

a contrasting band between the tyre and the centre of the wheel, partially

covered usually by a hubcap. Ace’s original

Rimbellishers were secured using a worm-drive type of fastening which ensured

the metal of the wheel suffered no damage but as other manufacturers entered

the market, the trend became to use a cheaper method of construction using

nothing more than multiple sprung tags and with the devices push-fitted into the well of the wheel, some scraping of the paint being inevitable. Rimbellisher (always with an initial capital)

was a registered trademark of the Ace company but the word quickly became

generic and was in the 1950s & 1960s used to describe any similar device. Interestingly, by the mid 1950s, Ace ceased

to use “rimbellisher” in its advertising copy and described the two ranges as “wheel

discs” and “wheel trims”.

The

early versions did nothing more than produce a visual effect but the stylists

couldn’t resist the opportunities and some rimbellishers grew to the extent

they completely blocked the flow of air through the vents in the wheels and

that adversely affected the cooling of the brakes, the use of some of the new generation

of full-wheel covers also having this consequence. The solution was to ensure there was some

airflow but to maintain as much as possible of the visual effect, what were

often added were little fins and for these to work properly, they needed to

catch the airflow so there were left and right-side versions, an idea used to

this day in the alloy wheels of some high-price machinery.

1969 Pontiac GTO with standard trim rings (left) and 1969 Pontiac GTO Judge supplied without trim rings (right).

Ace

in the early 1950s had distributers in the US and both their rimbellishers and full-wheel

covers were offered. They took advantage

of the design which enabled the same basic units to be used, made specific only

the substitution of a centre emblem which was varied to suit different

manufacturers. Ace’s market penetration for

domestic vehicles didn’t last because Detroit soon began producing their own

and within a short time they were elaborate and often garish, something which

would last into the twenty-first century.

The Americans soon forgot about the rimbellisher name and started

calling them trim-rings and they became a feature of the steel “sports wheels”

manufacturers offered on their high-performance ranges in the years before aluminium

wheels became mainstream products. The

trim-rings of course had a manufacturing cost and this was built into the price

when the wheels were listed as an option.

The cost of production wouldn’t have been great but interestingly, when

General Motors’ Pontiac division developed the “Judge” option for its GTO to

compete with the low-cost Plymouth Road Runner, the trim-rings were among the

items deleted. However, the Judge

package evolved to the point where it became an extra-cost option for the GTO with

the missing trim-rings about the only visible concession to economy.

Mercedes-Benz W111s: 1959 220 SE with 8-slot rimbellishers (left), 1967 250 SE with the briefly used solid rimbellishers (centre) and 1971 280 SE 3.5 with the later 12-slot rimbellishers which lacked the elegance of the 8-slots.

Like

many companies, Mercedes-Benz used wheel covers as a class identifier. When the W111 saloons (1959-1968) were

released in 1959, the entry-level 220 was fitted with just hubcaps while the up

market twin-carburetor 220 S and the fuel-injected 220 SE had rimbellishers (made

by the factory, not Ace). Within a few

years, the use of rimbellishers was expanded but by the mid-1960s, the elegant

8-slot units mostly had been replaced with a less-pleasing solid metal pressing

(albeit one which provided a gap for brake cooling). That didn’t last and phased-in between 1967-1968,

the company switched from the hubcap / rimbellisher combination to a one-piece

wheel cover which included the emulation of a 12-slot rimbellisher. There were no objections to the adoption of

one-piece construction but few found the new design as attractive as the

earlier 8-slot.

MG publicity photograph (left) showing MGA and Magnettes, the former fitted with the Cornercroft's Ace Rimbellishers which were a factory option. The MGA (right) uses a different third-party rimbellisher which was physically bigger and overlapped the edge of the rim to a greater degree. The factory-option is preferred by most because it better suits the MGA's delicate lines.

1958 Jaguar 3.4 (top) and 1960 MGA Coupé (bottom) with the relevant Ace-Mercury wheel discs.

As well as an after-market product sold through retail outlets and offered as a dealer-fitted accessory, the Ace-Mercury wheel discs were at various times a factory option, MG sometimes listing them for the MGA (1955-1962), ZA-ZB Magnettes (1953-1958) and early versions of both the MGB (1962-1980) & Midget (1961-1979). For Coventry-based Cornercroft (manufacturer of the Ace Mercury range), the attraction was the (more or less) standardized shape of steel wheels meant it was possible to use the one basic design in a variety of diameters (13, 14 & 15 inch), able to be marketed for use with vehicles from different makers simply by changing the centre-cap to a fitting with the name of the relevant marque (others would also use the same technique). Cornercraft also offered a (fake) eared spinner in the style of a knockoff nut but these seem never to have been factory options. The Ace-Mercury was made from bright anodized aluminium and thus was both lightweight and corrosion-resistant but somewhat fragile if subjected to stresses which steel would easily cope. Additionally, like many “big” wheel-covers, they could be prone to “popping-off” during hard cornering, a phenomenon familiar to students of the car chases in Hollywood movies between the 1960 and 1990s, the film pedants (of which there seem to be many) documenting instances where the “continuity girl” either failed to notice or ignore a wheel-cover inexplicably re-attached, mid-chase. All of this meant the survival rate of Ace-Mercury is low and many were anyway discarded as subsequent owners preferred the sexier look of wire, alloy or styled-steel wheels. That makes them now a valuable period-piece and it’s not unusual to see an MG, Riley or Jaguar driven to a show with bare wheels, the Ace-Mercurys put on only for the duration of the exhibition.

One difference from the usual practice was that unlike most hub-caps or wheel covers which tended to be the same for all four wheels, the Ace-Mercury’s small louvers operated as air scoops when the wheels were in rotation, ducting cooling air through the ventilation holes in the wheel to assist in cooling the brakes. A set for four was thus supplied in left & right-hand pairs and needed to be installed with the louvers’ open edge “facing the breeze”. That wasn’t unique but was untypical and the concept was sometimes made more intricate still, such as when the fourth-generation Chevrolet Corvette (C4, 1983-1996) was introduced with alloy wheels of a different width front & rear, meaning than for the cooling ducts to work there were four different wheels. Another quirk of the Ace-Mercury was that although the visual similarities make them all barely distinguishable except for the diameter, in January 1959, MG changed the design of the MGA’s disc wheels, competing Cornercroft to re-design to the internal structure (the MGA version’s left/right part numbers changing from 97H675/97H676 to BHA4165/BHA4166. Details like this litter the car restoration business which is why replicating exactly what was done decades ago can be both challenging and expensive.

1966 Jaguar Mark X with factory rimbellishers.