Glove (pronounced gluhv)

(1) A

shaped covering for the hand with individual sheaths for the fingers and thumb,

made of leather, fabric etc.

(2) To

cover with or as if with a glove; provide with gloves.

(3) In

specialized use (as golf glove, boxing glove, driving glove etc), any of

various protective or grip-enhancing hand covers worn in sports and related

pursuits.

(4) In

the rules of cricket, to touch a delivery with one's glove while the gloved

hand is on the bat. Under the rules of

cricket, the batsman is deemed to have hit the ball with the bat.

Pre 900: From the Middle English glove & glofe, from the Old English glōf, glōfe & glōfa (glove (weak forms attested only in plural form glōfan (gloves))), from the Proto-Germanic galōfô (glove), a construct of ga- (the collective and associative prefix) + lōfô (flat of the hand, palm), from the primitive Indo-European lāp-, lēp-, & lep- (flat). It was cognate with the Old Norse glōfi, the Scots gluve & gluive (glove) and the Icelandic glófi (glove). It was related to the Middle English lofe &, lufe (palm of the hand). The verb form “to cover or fit with a glove” emerged circa 1400, gloved & gloving followed later; Old English had adjective glofed. The surname Glover is recorded in parish records from the mid-thirteenth century. In German, Handschuh is the usual word for glove and translates literally as "hand-shoe"; the Old High German was hantscuoh and it exist in both Danish and Swedish as hantsche, all related to the Old English Handscio (the name of one of Beowulf's companions, eaten by Grendel) which was attested only as a proper name. Glove is a noun and verb, gloved is a verb & adjective, gloving is a verb and gloveless & glovelike are adjectives; the noun plural is gloves.

Glove etiquette in the 1950s. The high Cold War saw the last days during which "hats & gloves" really were a thing for upper middle class women in the West.

Glove appear often in English sayings" . "To throw down the glove" (often also as "throw down the gauntlet") is to offer a challenge (the act once a literal prelude to combat) and "to take up the glove" is to accept it. "Fits like a glove" (attested from 1771) indicates something perfect; to be "hand in glove" is to be in association with (often pejorative); to treat with "kid gloves" means gently to handle (the "kid" a reference to the soft hide of a young goat); to "hang up the gloves" (in the sense of a pugilist) is to retire. Again, drawn from boxing, to "take off the gloves" (when in a dispute or argument) is to continue ruthlessly without regard for the normal rules of conduct; boxing gloves apparently date from 1847. The phrase "iron fist in a velvet glove" describes well-disguised strength and was used of cars with an appearance which hinted little at their potential, things like the BMW M5s and Mercedes-Benz 500Es of the late twentieth century the classic examples.

Mitten (pronounced mit-n)

(1) A

hand covering enclosing the four fingers together and the thumb separately;

sometimes shortened to mitt.

(2) A

slang term for any form of glove (rare).

1350–1400:

From the Middle English miteyn & mitain, from the Old & Middle French

mitan, miton & mitaine (mitten; half-glove), from Old

French mitaine (Mitain noted as a surname

from the mid-thirteenth century). The

Modern French spelling is mitaine,

from the Frankish mitamo & mittamo (half), superlative of mitti (midpoint), from the Proto-Germanic

midjô & midją (middle, center), from the primitive Indo-European médhyos (between, in the middle, center). It was cognate with the Old High German mittamo & metemo (half, in the middle), the Old Dutch medemest (midmost) and the Old English medume (average, moderate, medium). Related to all was the Medieval Latin mitta of

uncertain origin but perhaps from the Middle High German mittemo & the Old

High German mittamo (middle, midmost

(reflecting the notion of "half-glove")), or from the Vulgar Latin medietana (divided in the middle) from

the Classical Latin medius. From circa 1755, a mitten was a "lace or

knitted silk glove for women covering the forearm, the wrist, and part of the

hand", a item of fashion for women in the early 1800s and revived at the

turn of the twentieth century. The now

obsolete colloquial phrase from the 1820s get

the mitten meaning “a man refused or dismissed as a lover", the notion

receiving the mitten instead of the hand.

The only derived for is the adjective mittenlike; mittened apparently

doesn’t exist.

Lindsay Lohan in gloves.

In general use, many things technically mittens are referred to as gloves. Boxing gloves for example don't have separate fingers but there is actually a boxing mitt. It features thicker knuckle padding compared to standard boxing gloves, designed to protect the hands from heavy boxing bag impacts. Manufacturers caution that while they can be used for pad work, their dense foam protection is not ideal for sparring sessions.

George HW Bush demonstrates the World War II era "V for Victory" sign (left) and Lindsay Lohan deploys her signature "peace sign".

World War II (1939-1945) veteran George HW Bush (1924–2018; US President (George XLI 1989-1993)) would have remembered Winston Churchill's (1875-1965; UK prime-minister 1940-1945 & 1951-1955) wartime "V for victory" sign and that’s the meaning the gesture gained in the US. Unfortunately he wasn’t aware of its significance in the antipodes: when given with the palm facing inwards, it’s the equivalent to the upraised middle finger in the US. On a state visit to Australia in 1992, while his motorcade was percolating through Canberra, he made the sign to some locals lining the road. What might have been thought a slight worked out well, the crowd lining the road cheering the gesture which must have been encouraging. That same day, the president gave a speech advocating stronger efforts “to foster greater understanding” between the American and Australian cultures. The Lakeland Ledger, reporting his latest gaffe, wrote, “...wearing mittens when abroad would be a beginning”.

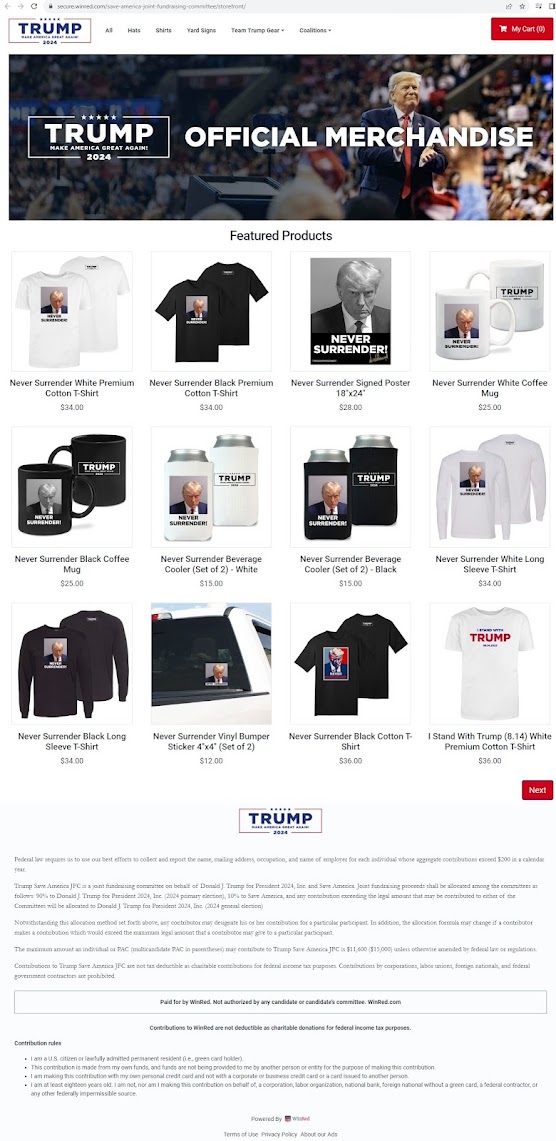

The consensus appeared to be the best approach is to adopt a neutral expression which expresses no levity and indicates one is taking the matter seriously. On that basis, Lindsay Lohan was either well-advised or was a natural as one might expect from one accustomed to the camera's lens. Among Donald Trump's alleged co-conspirators there was a range of approaches and the consensus of the experts approached for comment seemed to be that Rudy Giuliani's was close to perfect as one might expect from a seasoned prosecutor well-acquainted with the RICO (Racketeering Influenced and Corrupt Organizations) legislation he'd so often used against organized crime in New York City. Many of the others pursued his approach to some degree although there was the odd wry smile. Some though were outliers such as Jenna Ellis who smiled as if she was auditioning for a spot on Fox News and, of course, some of the accused may be doing exactly that. However, the stand-out was Donald Trump who didn't so much stare as scowl and it doubtful if his mind was on the judge or jury, his focus wholly on his own image of strength and defiance and the run-up to the 2024 presidential election because while returning to the White House wouldn't automatically provide the mechanisms to solve all his legal difficulties, it'd be at least helpful. In the short term Trump mug-shot merchandize became available, the Trump Save America JFC (joint fundraising committee) disclosing the proceeds from the sales of Trump mug-shot merchandize were allocated among the committees thus: 90% to Donald J. Trump for President 2024, Inc (2024 primary election) & 10% to Save America while any contribution exceeding the legal limit was allocated to the former.