Authentic (pronounced aw-then-tik)

(1) Something not false or copied; genuine; real.

(2) Having an origin supported by unquestionable

evidence; authenticated; verified: with certified provenance.

(3) Representing one’s true nature or beliefs; true to

oneself or to the person identified.

(4) Entitled to acceptance or belief because of agreement

with known facts or experience; reliable; trustworthy.

(5) In law, executed with all due formalities; conforming

to process.

(6) In music (of a church mode and most often applied to

the Gregorian chant), having a range extending from the final to the octave

above.

(7) In music (of a cadence), progressing from a dominant to a tonic chord.

(8) In musical performance, using period instruments and historically researched scores

and playing techniques in an attempt to perform a piece as it would have been

played at the time it was written (or in certain cases, first performed).

(9) Authoritative; definitive (obsolete).

1300–1350: From the Middle English authentik & autentik

(authoritative, duly authorized (a sense now obsolete)), from the Old French autentique (authentic; canonical (from

which thirteenth century Modern French gained authentique)), from the Late Latin authenticus (the work of the author, genuine ( which when used as a

neuter noun also meant “an original document, the original”), from the Ancient Greek

αὐθεντικός (authentikós)

(original, primary, at first hand), the construct being αὐθέντης (authéntēs)

(lord, master; perpetrator (literally, “one who does things oneself; one who acts independently (the construct being aut(o-) (self-) + -hentēs (doer)) + -ikos (–ic)

(the adjective suffix)), from the primitive Indo-European root sene- (to accomplish, to achieve). The alternative spellings authentical, authentick, authenticke & authentique are all archaic.

Authentic is an adjective (and a non-standard noun), authentically is an

adverb, authenticity & authentification

are nouns, authenticate, authenticating &

authenticated are verbs; the most common noun plural is authentifications.

The modern sense of something “real, entitled to

acceptance as factual” emerged in the mid-fourteenth century and synonyms

(depending on context) include true, veritable, genuine, real, bonafide, bona

fide, unfaked, reliable, trustworthy, credible & unfaked. As antonyms (the choice of which will be

dictated by context and sentence structure) the derived adjectives include: non-authentic,

inauthentic & unauthentic (the three usually synonymous but nuances can be

constructed depending on the context) and the curious quasi-authentic, used

presumably to suggest degrees of fakeness, sincerity etc). Inauthentic from 1783 is the most often used

and thus presumably the preferred form and in this it competes also with phony,

fake, faux, bogus, imitation, clone, impersonation, impression, mimic, parody,

reflection, replica, tribute, reproduction, apery, copy, counterfeit, ditto,

dupe, duplicate, ersatz, forgery, image, likeness, match, mime, mimesis,

mockery, parallel, resemblance, ringer, semblance, sham, simulacrum,

simulation, emulation, takeoff, ripoff, transcription, travesty, Xerox, aping,

carbon copy, echo, match, mirror, knockoff, paraphrasing, parroting,

patterning, representation & replica & the rare ingenuine. The verb authenticate (verify, establish the

credibility of) dates from the 1650s and was from the Medieval Latin authenticatus, the past participle of authenticare, from the Late Latin authenticus; the form of use in the mid

seventeenth century was sometimes “render authentic”. The noun authenticity (the quality of being

authentic, or entitled; acceptance as to being true or correct) dates from the 1760

and replaced the earlier authentity (1650s)

& authenticness (1620s).

Concurring with the 2016 ruling of the New York County Supreme Court which, on appeal, also found for the game’s makers (Take-Two, aka Rockstar) , the judges, as a point of law, accepted the claim a computer game’s character "could be construed a portrait", which "could constitute an invasion of an individual’s privacy" but, on the facts of the case, the likeness was "not sufficiently strong". The “… artistic renderings are an indistinct, satirical representation of the style, look and persona of a modern, beach-going young woman... that is not recognizable as the plaintiff" Judge Eugene Fahey wrote in his ruling. Judge Fahey's words recalled those of Potter Stewart (1915–1985; associate justice of the US Supreme Court 1958-1981) when in Jacobellis v Ohio (378 U.S. 184 (1964) he wrote: “I shall not today attempt further to define… and perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it…” Judge Fahey knew a basic white girl when he saw one; he just couldn't name her. Lindsay Lohan's lawyers did not seek leave to appeal.

The game’s developers may have taken the risk of incurring Lindsay Lohan’s wrath and indignation because they’d been lured into a false sense of security by Crooked Hillary Clinton (b 1947; US secretary of state 2009-2013) not filing a writ after a likeness of her appeared on GTA 4’s (2008) Statue Of Happiness which stands on Happiness Island, just off the coast of Liberty City. The Statue of Happiness was a blatant knock-off of the New York’s Statue of Liberty and crooked Hillary became a determined and acerbic critic of Rockstar and the GTA franchise after the “Hot Coffee” scandal. That controversy arose after modders promulgated a code which in GTA: San Andreas’ release (2004) unlocked a hidden “mini-game” which allowed players to control explicit on-screen sex acts. Men having sex with women with whom they don’t enjoy benefit of marriage is a bit of a sore point with crooked Hillary, then a US senator (Democrat-NY), who embarked on a campaign for new regulations be imposed on the industry and the most immediate consequence was the SSRB (Entertainment Software Rating Board) launching an investigation, subsequently raising GTA: San Andreas’ rating from “M” (Mature) to “AO” (Adults Only 18) until the objectionable content was removed. For those who wondered if the frightening visage on the GTA 4 statute really was what some suspected, the object’s file name was “stat_hilberty01.wdr”.

Roskstar's Statue Of Happiness in GTA 4 (2008, left) and an official photograph of crooked Hillary Clinton (right).

Rockstar seeking vengeance was understandable because crooked Hillary’s moral crusade proved tiresome for the company. Once the ESRB had been nudged into action, crooked Hillary petitioned the FTC (Federal Trade Commission) to (1) find the source of the game's “graphic pornographic and violent content”, (2) determine if it should be slapped with an AO rating and (3) “examine the adequacy of the retailers' rating enforcement policies.” Not content, she then announced she’d be sponsoring in the Senate a bill for an act which would make it a federal crime (with a mandatory US$5,000 fine) to sell to anyone under 18, violent or sexually explicit video games; the Family Entertainment Protection Act was filed on 17 December 2005 and referred to the Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation, where quietly it was allowed to expire.

While the act slowly was being strangled in committee hearings, the FTC and Rockstar reached a settlement, the commission ruling the company had violated the Federal Trade Commission Act (1914) by failing to disclose the inclusion of “unused, but potentially viewable” explicit content” (that it was enabled by a third party was held to be “not relevant”). The settlement required Rockstar “clearly and prominently disclose on product packaging and in any promotion or advertisement for electronic games, content relevant to the rating, unless that content had been disclosed sufficiently in prior submissions to the rating authority” with violations punishable by a fine of up to US$11,000. In the spirit of the now again fashionable Calvin Coolidge (1872-1933; US president 1923-1929) era capitalism, no fine was imposed for the “Hot Coffee incident”, presumably because the company had already booked a US$24.5 million loss from the product recall earlier mandated.

Real & fake appears as simple and obvious a dichotomy

as black & white but humanity has managed over the millennia to create many

grey areas in many shades, thus the wealth of antonyms and synonyms for

“authentic”. Authentic now carries the

connotation of an authoritative confirmation (which can be formalized as a

process which culminates with the issue of a “certificate of authenticity”

although the usefulness of that of course depends on the issuing authority

being regarded as authentic. Genuine carries

a similar meaning but in a less formalized sense and in some fields (such as

the art market), something can simultaneously be genuine yet not authentic (a painting

might for example be a genuine seventeenth century oil on canvas work yet not

be the Rembrandt it was represented to be; it’s thus not authentic). The word real is probably the most simple

term of all and can often be used interchangeably but unless what’s being

described is unquestionable “real” in every sense, more nuanced words may be

needed. Veritable was from the Middle

French veritable, from the Old French veritable, from the Latin veritabilis,

from vēritās (truth), the construct being vērus (true; real) + -tās (the suffix used to form abstract nouns). The

traditional of use in English however means veritable had become an expression

of admiration (eg “she is a veritable saint”) rather than a measure of

truthfulness or authenticity.

Other nuances also organically have evolved. Authentic now implies the contents of the

thing in question correspond to the facts and are not fictitious while genuine

implies that whatever is being considered is something unadulterated from its

original form although what it contains may in some way be inauthentic. This is serviceable and as long as it’s not

used in a manner likely to mislead is a handy linguistic tool but as Henry

Fowler (1858–1933) noted in his A

Dictionary of Modern English Usage (1926), it was an artificial

distinction, “…illustrated by the fact

that, “genuine” having no verb of its own, “authenticate” serves for both”.

Degrees of authenticity: 2016 Jaguar XKSS (continuation series)

In 2016 Jaguar displayed the first of nine XKSS "continuation" models. In 1957, Jaguar had planned a run of 25 XKSSs which were road-going conversions of the Le Mans-winning D-type (1954-1956). Such things were possible in those happier, less regulated times. However, nine of the cars earmarked for export to North America were lost in fire so only 16 were ever completed. These nine, using the serial numbers allocated in 1957 are thus regarded as a "continuation of the original run" to completion, Jaguar insisting it is not "cloning itself". The project was well-received and the factory subsequent announced it would also continue the production run of the lightweight E-Types, again using the allocated but never absorbed ID numbers. Other manufacturers, including Aston Martin, have embarked on their own continuation programmes and at a unit cost in excess of US$1 million, it's a lucrative business.

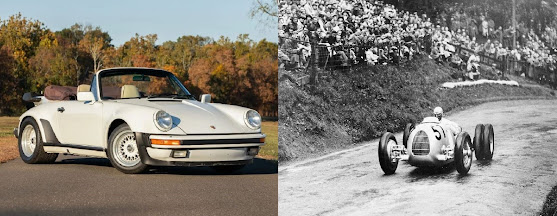

In the upper (or at least the most obsessional) reaches of the collector car market, the idea of “authenticity” is best expressed as “originality”. As early as the 1950s when the market began to the process of assuming its present form, originality was valued because many of the pre-war machines first to attract interest (Bentley, Rolls-Royce, Lagonda et al from the UK, Duisenberg, Stutz, Cadillac et al from the US and Mercedes-Benz, Isotta Fraschini, Bugatti et al from Europe) had over the years receive different coachwork from that which was originally supplied. At the time however, the contemporary records suggest that if a rakish new body had replaced something dowdy, it was a matter for comment rather than objection. Nor were replacement engines and transmissions thought objectionable as long as they replicated the originals, there then being an understanding things wear out. Those mechanical components were however among the first to come to the attention of the originality police and “matching numbers” became a thing, every stamped component with a serial number (engine blocks & heads, transmission cases, differential housings etc) which could be verified against factory records, made a car more collectable and thus more valuable. It was a matter of originality which came to matter, not functionality which mattered; a newer, better engine detracted from the value. In some cases originality was allowed to be a shifting concept especially with vehicles used in competition; if a Ferrari was found to be on its third engine, that was fine as long as each swap was performed, in period, by the factory or its racing team.

That exception aside, it’s now very different and, all else being equal, the most authentic collectable of its type is the one most original. These days collectors will line up their possessions in rows to be judged by “certified judges” who, clipboards in hand will peak and poke, ticking or crossing the boxes as they go. They’re prepared to concede the air in the tyres, the fuel in the tank and the odd speck of dust on the carpet may not be what was there when first the thing left the factory but points will be deducted for offenses such as incorrect screw heads, or a hose clap perhaps being installed clockwise rather than anti-clockwise. Sometimes a variation from the original can’t be detected, even by a certified judge. If a component (without a verifiable serial number) has been replaced with a genuine factory part number, if done properly that will often get a tick whereas a reproduction part from a third-party manufacturer will often have some barely discernible difference and thus get a cross.

Given the money which churns around the market, there’s a bit of an informal industry in faking authenticity and with some vehicles it is actually technically possible exactly to take a mundane version of something and emulate a more desirable model; the difference in value potentially in the millions. In some cases however, even if technically possible, it may be functionally not: If it’s notorious that only ten copies were produced of a certain model and all have for decades been accounted for, it’s not plausible to possess an eleventh. However, there are instances where the combination of (1) the factory not maintaining the necessary records and (2) the vehicle itself not being fitted with the requisite stampings or identification plates to determine exactly what options may originally have been fitted. However, even if documented and thus "authenticated", there can still be pitfalls. In the collectable market for vehicles (Ford, Lincoln & Mercury) produced in the US by the Ford Motor Company (FoMoCo) between 1967-2017, the gold standard is the service offered by mechanical engineer Kevin Marti's (b 1957) Marti Auto Works. That company has been licensed by FoMoCo to generate reports detailing the specification (mechanical, trim, options) on the day it left the factory, all data grabbed directly from Ford's databases. Available at three price-point (Standard, Deluxe & Elite), a Marti report is a valuable resource for both buyers and sellers. However, what the reports provide is what is in the database and that reflects the specification with which a vehicle should have been built and while the phrase "Monday & Friday cars" (popularized by Arthur Hailey's (1920-2004) novel Wheels (1971)) shouldn't be taken literally, its currency in the era was an indication mistakes did happen on car production lines and, given the factories were every day producing them in the thousands, that should not be a surprise. QC (quality control) inspections meant many E&O (errors and omissions) were rectified but some did slip through and while most were minor enough to be corrected by dealers, if the buyer was content to be appeased with a partial refund or credit, a vehicle could enter the wild with a specification in some way different from what was recorded in FoMoCo's database. Only a comparatively tiny number of such vehicles each year appeared but if a vehicle represented as "original" or "matching numbers" varies in some detail from the authoritative Marti Report, a seller will benefit if in possession of additional explanatory documents. Interestingly, the Marti Auto Works service is available because FoMoCo kept their old records in archives whereas Chrysler and General Motors (GM) did not.

Because of the way the data details were recorded on the tags attached to Chevrolet’s vehicles during this era it can be difficult for collectors always to verify a car as presented is in quite the form it was when first it emerged from the factory. Quite a few 1967 Impalas have been modified to “become” and SS 427 and it can take an expert to authenticate the real thing, the difference between one and another meaning tens of thousands of dollars in value. Fortunately, there are many experts and they are needed to distinguish between the clones and the real SS 427s (the model achieving 2,124 sales in 1967, 1,778 in 1968 and 2,455 in its swansong season in 1969. The 1967 Chevrolet SS 427 is now a collectable but it’s also a pedant’s delight because (1) although Impala-based it’s not by most treated as an Impala (this is contested) and (2) there was also a 1967 Impala SS 427 which is similar but not identical; technically, the SS 427 was a full-sized Chevrolet with RPO (regular production option) Z24. In collector terms, the things were not especially rare but the ecosystem of Chevrolet’s full-sized SS range was by then in decline; from a peak of almost 240,000 SS Impalas in 1965, volumes just two years later had fallen by some by over 80% to just 40,000 as customer interest shifted to the smaller, lighter pony cars and intermediates. It was a trend affecting all manufacturers and even before the muscle car era ended, the high-performance, full-sized segment would be driven to extinction, not by government pressure or edict but by lack of interest.

Chevrolet’s SS (Super Sport) option was released in 1961 as a bundle available for Impalas with high-performance V8s: it featured both suspension modifications and dress-up items including unique body and interior trim, power steering, power brakes with sintered metallic linings, full wheel covers with a three blade spinner, a passenger grab bar, a console for the floor shift, and a tachometer on the steering column. In that year, Chevrolet built close to half a million Impalas but only 453 buyers (a scant 142 of whom selected the top 409 cubic inch (6.7 litre) engine) opted for what was (at US$53.80) the bargain-priced SS package, an indication the marketing needed to be tweaked. The problem was that Chevrolet had intended the 1961 SS live up to its name and it was available only with the 348 (5.7) & 409 V8s which could be quite raucous and were notably thirstier than many were prepared to tolerate, even then. What dealers noted was how buyers were drawn to the style but put off by the specification which demanded much more from the driver that the smaller-engined models which wafted effortlessly along, automatic transmissions by now the default choice for most Impala buyers.

So the sales barrier was the implication of the costs attached to the SS bundle rather than the attractiveness. The headline number of US$53.80 actually included only the "spinner" wheel covers, SS badges, a shiny floor plate for the four-speed's shifter and a Corvette-style grab-bar for the glove-box (Ralph Nadar (b 1934) noted that one). However, ticking the SS option box triggered a list of "mandatory options" (a seeming oxymoron Detroit came to adore) including wider tyres (with compulsory narrow-band whitewalls), PAS & PB, (power assisted steering & power brakes), LPO (Limited Production Option) 1108 (Police Handling Package, a bundle including HD (heavy-duty) suspension components and sintered metallic brake linings), a steering column mounted 7000 rpm tachometer and a padded dashboard (the last little more than reassuringly decorative and unlikely much to impress Mr Nader). Having agreed to pay for all that, the buyer then had to decide whether to opt (at progressively increasing cost) for the 348 (with 305, 340 or 350 horsepower (HP)) or 409 (360 HP). The Powerglide two-speed automatic transmission was available only with the mildest of the 348s, further limiting the sales potential, the three or four-speed manual otherwise obligatory. In 1961, it was much more expensive to buy a SS Chevrolet than the US$53.80 on the brochure suggested and however pleasing, it was a long way removed from Chevrolet's traditional place as the low-priced rung on the "Sloan ladder". The decision was thus taken for 1962 to make the "show" available without the "go" and the SS became an "appearance package", available with even six-cylinder engines. Sales skyrocketed and between 1962-1969 some 920,000 SS packages were sold for the full-sized line; it was for years a handy revenue sub-centre.

GM had noted the dress-up bits were just Chevrolet part-numbers which could be ordered by dealers, some of which received customer requests separately to fit the trim pieces so some 1961 Impalas did to some extent resemble the SS cars though without the high-performance equipment. Thus from 1962 the SS option became widely available and consisted of bling and accessories, able to be ordered with even the most modest engines. Splitting the market between drag-strip monsters and boulevard cruisers which could be made to look much the same proved a great success. It was obvious there were more buyers who wanted their Impala to look like a a fast one than were able or prepared to pay for the experience and Chevrolet’s “SS appearance package” proved influential, the approach becoming a a template for the whole industry, spreading internationally, the Porsche 911T Lux (1972-1973) an example. The entry level 911T was the least powerful of the range and lacked some of the luxury fittings of the more expensive and more powerful 911E & 911S but for those who wanted the fittings but had no desire (or willingness to pay) for the horsepower, the 911T Lux was created which combined the mechanical specification of the "T" with the trim of the "S", the factory doing exactly what so many of Chevrolet's SS customers settled on after 1962.

Starting in 1967, beyond the standard-issue SS models, buyers could also choose the SS 427 model (RPO Z24) but confusingly, an Impala SS could be ordered with the 427 cubic inch (7.0 litre) V8 a situation which continued until the 1969 model year when, according to Chevrolet, only the SS 427 was available despite the company that year adding the “Impala” badges not used on the SS 427s in 1967 & 1968. It’s little wonder the big-bodied 427s of those three years confuse many. The flavours of the 427 V8 offered over the years also bounced around: For 1967, only the 385 horsepower (HP) L36 was available, the choice the next year extended to the L36 (390 HP) & L72 (425 HP), that pair augmented in 1969 by the LS1 (335 HP). Curiously a triple-carburetor option had been scheduled to appear on the 1967 SS 427 (and the Camaro) but both were cancelled after one of GM’s many corporate edicts, the three simulated stacks on the hood (bonnet) a relic of the late change of plans.

According to Chevrolet's fall 1966 brochure the SS 427 was: “The ’67 Super Sports by Chevrolet” which sounds definitive but whether the 1967 & 1968 SS 427s are really Impalas still is discussed between two factions, both with entrenched positions and it's unlikely minds ever have been changed. It’s something like the 1948 debate about the existence of God between British Jesuit priest & historian of philosophy Frederick Copleston (1907–1994) and noted atheist, British mathematician & philosopher Bertrand Russell (Third Earl Russell, 1872–1970): When someone with a sincere belief debates with someone with a sincere lack of belief, opinions are unlikely to change. One faction argues that because no “Impala” badge appears anywhere on the 1967-1968 cars then obviously they're not Impalas while the other points out that in every other aspect they're obviously Impalas before playing their trump card: the stylized “leaping impala” emblem, prominently which sits in the middle of the rear seat. So it’s a matter of whether “symbol trumps (lack of) text” which seems one of the industry’s more sterile debates though it has never gone away and that the Impala badge returned for 1969 presumably can be interpreted to afforce the theories of either side. Nothing in the VIN (vehicle identification number) reflects whether a full-size Chevrolet is a SS 427 or another model so an original build sheet and/or window sticker with the vital Z24 reference will be the best evidence. There are now many 1967-1969 SS 427 "clones" (fake, faux, tribute, reproduction & replica the other terms used depending on circumstances and claims asserted) and the authentication of what's genuine and what's not is a minor industry in the collector market.

Authenticity in art

The matter of

authenticity is obviously important in the art market. Usually the critical factor is the identity

of the artist. In May 1945, immediately

after the liberation from Nazi occupation of the Netherlands, the authorities

arrested Dutch national Han van Meegeren (1889–1947) and charged him with

collaborating with the enemy, a capital crime.

Evidence had emerged that van Meegeren had during World War II (1939-1945) sold Vermeer's Christ with the Woman Taken in

Adultery to Hermann Göring (1893–1946; prominent Nazi 1922-1945,

Reichsmarschall 1940-1945). His defense

was as novel as it was unexpected: He claimed the painting was not a Vermeer

but rather a forgery by his own hand, pointing out that as he had traded the

fake for over a hundred other Dutch paintings purchased (frequently transactions of dubious legality) earlier by the Reichsmarschall, he was thus a national hero rather than a Nazi collaborator. Understandably, the judges were sceptical but, in the courtroom, he provided a practical demonstration of his skill,

added to his admission having forged five other fake "Vermeers"

during the 1930s, as well as two "Pieter de Hoochs" all of which had

shown up on European art markets since 1937. He convinced the court and was

acquitted but was then, as he expected, charged with forgery for which he

received a one year sentence, half the maximum available to the court. He died in prison of heart failure, brought

on by years of drug and alcohol abuse.

His skills with brush and paint aside, Van Meegeren was able successfully to pass off his 1930s fakes as those of a seventeenth century painter of the Dutch Golden Age (not all critics agree Vermeer should be classified an "artist of the baroque" despite the timing) because of the four years he spent meticulously testing the techniques by which a "new" painting could be made to appear, even to experts, centuries old. The breakthrough was getting the oil-based paints thoroughly to harden, a process which occurs naturally over fifty-odd years, his novel solution being to mix the pigments not with oil but the synthetic resin Bakelite. For his canvases, he used genuine but worthless seventeenth-century paintings, removing as much of the picture as possible, scrubbing carefully with pumice and water, taking the utmost care not to lose the network of cracks, the existence of which would play a role in convincing many expert appraisers they were authentic Vermeers. Once dry, he baked the canvas and rubbed a carefully concocted mix of ink and dust into the edges of the cracks, emulating the dirt which would, over centuries, accumulate.

Modern x-ray techniques and chemical analysis

mean such tricks can no longer succeed but, at the time, so convincing were his

fakes no doubts were expressed and the dubious Christ with the Woman Taken in Adultery became Göring's most prized

acquisition, quite something given the literally thousands of pieces of art he

looted from Europe. One of the Allied

officers who interrogated Göring in Nuremberg prison prior to his trial

(1945-1946) recorded that the expression on his face when told "his

Vermeer" was a fake suggested that "...for the first time Göring realized there really was evil in this world".

So the

identity of the painter matters, indeed, between 1968-2014, there was a

standing institution called the Rembrandt Research Project (RRP), an initiative

of the Nederlandse Organisatie voor

Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (the NOW; the Netherlands Organization for

Scientific Research), the charter of which included authenticating all works attributed

to the artist (Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606-1669). That was a conventional approach to authentication

but there are others. In the West

there’s a long standing distinction between “high art” and “popular art” but

not all cultures have that distinction and when the output of artists from

those cultures is commoditised, what matters is ethnicity. In Australia, the distinctive paintings

categorized as “indigenous art” have become popular and are a defined market

segment and what determines their authenticity is that they are legitimately

and exclusively the work of indigenous artists.

The styles, of which dot painting is the best known, are technically not

challenging to execute and thus easy to replicate by anyone and this has caused

where non-indigenous hands have been found (or alleged) to be involved in the

process.

The Times (London), 8 March 1997.

In

1997, Elizabeth Durack (1915–2000), a Western Australian disclosed that the

much acclaimed works of the supposed indigenous artist “Eddie Burrup” had

actually been painted by her in her studio, Eddie Burrup her pseudonym. To make matters worse, prior to her

revelation, some of the works had been included in exhibitions of Indigenous

Australian art. Although noted since the

1980s, the phrase “cultural appropriation” wasn’t then widely used outside of

academia of activist communities but what Ms Durack did was a classic example

of a representative of a dominant culture appropriating aspects of marginalized

or minority cultures for some purpose.

Sometimes (perhaps intentionally) misunderstood, the critical part of cultural

appropriation is the relationship between the hegemonic and the marginal; a

white artist creating work in the style of an indigenous, colonized people and

representing it in a manner which suggests it’s the product of an indigenous

artist is CA. Condoleezza Rice (b 1954;

US secretary of state 2005-2009) playing Chopin on a Steinway is not; that’s

cultural assimilation. Once the truth

was known, the works were removed from many galleries where they had hung and

presumably the critical acclaim they had once received was withdrawn. Both responses were of course correct. Had Ms Durack represented the works as her

own and signed them thus that would have been cultural appropriation and people

could have responded as they wished but to represent them as the works of

someone with a name all would interpret as that of an indigenous artist was

both cultural appropriation and deceptive & misleading conduct with all

that that implies.

More

recently, there have been accusations white staff employed in a commercial

gallery where indigenous Australian artists are employed to create paintings have been

influenced, assisted or interfered with (depending on one’s view) in the

production process. According to the

stories run in the Murdoch press, a white staff member was filmed suggesting

some modification to an artist although whether this was thought to be on

artistic grounds or an attempt to make something more resemble "what sells best" isn’t clear. However, in a sense the

motive doesn’t matter because the mere intervention detracts from the authenticity

of the product, based as it is not on the inherent artistic merit but on the

artist being indigenous. In that the

case was conceptually little different from Göring’s “Vermeer” which for years

countless experts in fine art had acclaimed as a masterpiece while it hung in

Carinhall, an opinion not repeated as soon as its dubious provenance was

revealed. Nor is it wholly dissimilar to

the case of the replica 1962 Ferrari 250 GTO which is essentially a carbon copy

of one of the 40-odd originals made (indeed it was in some ways technical

superior) yet it is worth US$1.2 million while the record price for a genuine

one was US$70 million. So for a product

to be thought authentic can depend on (1) that it was created by a certain

individual, (2) that it was created by a member of a certain defined ethnicity

or (3) that it was created by a certain institution.

In art,

authenticity is precious in more than one sense.

Salvator Mundi, the critics admit, is

not an exceptional painting but once authenticated as the work of Leonardo, it created its own exceptionalism, in 2017 becoming the most

expensive painting ever sold at public auction, attracting US$450 million when offered

by Christie's auction house in New York. The criteria

for assessing the works of indigenous artists is also beneficial for them

because unlike mainstream art, they’re not assessed as good or bad but merely

as authentically indigenous or not.

That’s why there are no bad reviews of indigenous art or performance because (1) the

concept is irrelevant, (2) such an idea is claimed to be alien to indigenous peoples and (3) if expressed by white critics would represent the

imposition of a Western cultural construct on a marginalized group. Dot paintings and such are marketed through

the structures of the art market because physically they’re similar objects

(size, weight etc) to other paintings but they’re really modern, mass-produced

artefacts which depend on provenance as much as a Chevrolet SS 427, Ferrari 250 GTO, Leonardo or Vermeer.