Dot (pronounced dot)

(1) A small, roundish mark made with or as if with a pen.

(2) A minute or small spot on a surface; speck.

(3) Anything relatively small or speck-like.

(4) A small specimen, section, amount, or portion; a

small portion or specimen (the use meaning “a lump or clod” long obsolete).

(5) In grammar, a punctuation mark used to indicate the

end of a sentence or an abbreviated part of a word; a full stop; a period.

(6) In the Latin script, a point used as a diacritical

mark above or below various letters, as in Ȧ, Ạ, Ḅ, Ḃ, Ċ.

(7) In computing, a differentiation point internet

addresses etc and in file names a separation device (although historically a

marker between the filename and file type when only one dot per name was

permitted in early files systems, the best known of which was the 8.3 used by the

various iterations of CP/M & DOS (command.com, image.tif, config.sys etc).

(8) In music, a point placed after a note or rest, to

indicate that the duration of the note or rest is to be increased one half. A

double dot further increases the duration by one half the value of the single

dot; a point placed under or over a note to indicate that it is to be played

staccato.

(9) In telegraphy. a signal of shorter duration than a

dash, used in groups along with groups of dashes (-) and spaces to represent

letters, as in Morse code.

(10) In printing, an individual element in a halftone

reproduction.

(11) In printing, the mark that appears above the main

stem of the letters i, j.

(12) In the sport of cricket, as “dot ball” a delivery

not scored from.

(13) In the slang of ballistics as “dotty” (1) buckshot, the

projectile from a or shotgun or (2) the weapon itself.

(14) A female given name, a clipping of form of Dorothea or

Dorothy.

(15) A contraction in many jurisdictions for Department

of Transportation (or Transport).

(16) In mathematics and logic, a symbol (·) indicating

multiplication or logical conjunction; an indicator of dot product of vectors:

X · Y

(17) In mathematics, the decimal point (.),used for

separating the fractional part of a decimal number from the whole part.

(18) In computing and printing, as dot matrix, a

reference to the method of assembling shapes by the use of dots (of various

shapes) in a given space. In casual (and

commercial) use it was use of impact printers which used a hammer with a dot-shape

to strike a ribbon which impacted the paper (or other surface) to produce

representations of shapes which could include text. Technically, laser printers use a dot-matrix in

shape formation but the use to describe impact printers caught on and became

generic. The term “dots per inch” (DPI) is

a measure of image intensity and a literal measure of the number of dots is an

area. Historically, impact printers were

sold on the basis of the number of pins (hammers; typically 9, 18 or 24) in the print head which was

indicative of the quality of print although some software could enhance the

effect.

(19) In civil law, a woman's dowry.

(20) In video gaming, the abbreviation for “damage over

time”, an attack that results in light or moderate damage when it is dealt, but

that wounds or weakens the receiving character, who continues to lose health in

small increments for a specified period of time, or until healed by a spell or

some potion picked up.

(21) To mark with or as if with a dot or dots; to make a

dot-like shape.

(22) To stud or diversify with or as if with dots (often

in the form “…dotting the landscape…” etc).

(23) To form or cover with dots (such as “the dotted line”).

(24) In colloquial use, to punch someone.

(25) In cooking, to sprinkle with dabs of butter, chocolate

etc.

Pre 1000: It may have been related to the Old English dott (head of a boil) although there’s

no evidence of such use in Middle English.

Dottle & dit were both derivative of Old English dyttan (to stop up (and again, probably

from dott)) and were cognate with Old

High German tutta (nipple), the Norwegian

dott and the Dutch dott (lump). Unfortunately there seems no link between dit and the modern slang zit (pimple), a

creation of US English unknown until the 1960s.

The Middle English dot & dotte were from the Old English dott in the de-elaborated sense of “a

dot, a point on a surface), from the Proto-West Germanic dott, from the Proto-Germanic duttaz

(wisp) and were cognate with the Saterland Frisian Dot & Dotte (a clump),

the Dutch dot (lump, knot, clod), the

Low German Dutte (a plug) and the Swedish

dott (a little heap, bunch, clump). The use in civil jurisdiction of common law where

dot was a reference to “a woman's dowry” dates from the early 1820s and was

from the French, from the Latin dōtem,

accusative of dōs (dowry) and related

to dōtāre (to endow) and dāre to (give). For technical or descript reasons dot is a

modifier or modified as required including centered dot, centred dot, middle

dot, polka dot, chroma dot, day dot, dot-com, dot-comer (or dot-commer), dot

release and dots per inch (DPI). The synonyms

can (depending on context) include dab, droplet, fleck, speck, pepper, sprinkle,

stud, atom, circle, speck, grain, iota, jot, mite, mote, particle, period, pinpoint,

point, spot and fragment. Dot & dotting

are nouns & verbs, dotter is a noun, dotlike & dotal are adjectives, dotted

is an adjective & verb and dotty is a noun & adjective; the noun plural

is dots.

Although in existence for centuries, and revived with the modern meaning (mark) in the early sixteenth century, the word appears not to have been in common use until the eighteenth and in music, the use to mean “point indicating a note is to be lengthened by half” appears by at least 1806. The use in the Morse code used first on telegraphs dates from 1838 and the phrase “on the dot” (punctual) is documented since 1909 as a in reference to the (sometimes imagined) dots on a clock’s dial face. In computing, “dot-matrix” (printing and screen display) seems first to have been used in 1975 although the processes referenced had by then been in use for decades. The terms “dotted line” is documented since the 1690s. The verb dot (mark with a dot or dots) developed from the noun and emerged in the mid eighteenth century. The adjective dotty as early as the fourteenth century meant “someone silly” and was from "dotty poll" (dotty head), the first element is from the earlier verb dote. By 1812 it meant also literally “full of dots” while the use to describe shotguns, their loads and the pattern made on a target was from the early twentieth century. The word microdot was adopted in 1971 to describe “tiny capsules of Lysergic acid diethylamide" (LSD or “acid”); in the early post-war years (most sources cite 1946) it was used in the espionage community to describe (an extremely reduced photograph able to be disguised as a period dot on a typewritten manuscript.

Lindsay Lohan in polka-dots, enjoying a frozen hot chocolate, Serendipity 3 restaurant, New York, 7 January 2019.

The polka-dot (a pattern consisting of dots of uniform

size and arrangement," especially on fabric) dates from 1844 and was from

the French polka, from the German Polka, probably from the Czech polka, (the dance, literally

"Polish woman" (Polish Polka),

feminine form of Polak (a Pole). The word might instead be a variant of the

Czech půlka (half (půl the truncated version of půlka used in special cases (eg telling

the time al la the English “half four”))) a reference to the half-steps of

Bohemian peasant dances. It may even be

influenced by or an actual merger of both.

The dance first came into vogue in 1835 in Prague, reaching London in

the spring of 1842; Johann Strauss (the younger) wrote many polkas. Polka was a verb by 1846 as (briefly) was polk; notoriously it’s sometimes

mispronounced as poke-a-dot.

In idiomatic use, to “dot one's i's and cross one's t's”

is to be meticulous in seeking precision; an attention to even the smallest

detail. To be “on the dot” is to be

exactly correct or to have arrived at exactly at the time specified. The ides of “joining the dots” or “connecting

the dots” is to make connections between various pieces of data to produce

useful information. In software, the

process is literal in that it refers to the program “learning: how accurately

to fill in the missing pieces of information between the data points generated

or captured. “The year dot” is an informal

expression which means “as long ago as can be remembered”. To “sign on the dotted line” is to add one’s

signature in the execution of a document (although there may be no actual

dotted line on which to sign).

Dots, floating points, the decimal point and the Floating Point Unit (FPU)

When handling numbers, decimal points (the dot) are of

great significance. In cosmology a tiny

difference in values beyond the dot can mean the difference between hitting one’s

target and missing by thousands of mile and in finance the placement can

dictate the difference between ending up rich or poor. Vital then although not all were much

bothered: when Lord Randolph Churchill (1849–1895) was Chancellor of the Exchequer

(1886), he found the decimal point “tiresome”, telling the Treasury officials “those

damned dot” were not his concern and according to the mandarins he was inclined

to “round up to the nearest thousand or million as the case may be”. His son (Winston Churchill (1875-1965; UK

prime-minister 1940-1945 & 1951-1955) when Chancellor (1924-1929)) paid

greater attention to the dots but his term at 11 Downing Street, although

longer, remains less well-regarded.

In some (big, small or complex) mathematical computations

performed on computers, the placement of the dot is vital. What are called “floating-point operations”

are accomplished using a representation of real numbers which can’t be handled

in the usual way; both real numbers, decimals & fractions can be defined or

approximated using floating-point representation, the a numerical value represented

by (1) a sign, (2) a significand and (3) an exponent. The sign indicates whether the number is

positive or negative, the significand is a representation of the fractional

part of the number and the exponent determines the number’s scale. In computing, the attraction of floating-point

representation is that a range of values can be represented with a relatively

small number of bits and although the capability of computers has massively increased,

so has the ambitions of those performing big, small or complex number

calculations so the utility remains important.

At the margins however (very big & very small), the finite precision

of traditional computers will inevitably result in “rounding errors” so there can

be some degree of uncertainty, something compounded by there being even an “uncertainty

about the uncertainty”. Floating point

calculations therefore solve many problems and create others, the core problem

being there will be instances where the problems are not apparent. Opinion seems divided on whether quantum

computing will mean the uncertainty will vanish (at least with the very big if

not the very small).

In computer hardware, few pieces have so consistently

been the source of problems as Floating point units (FPUs), the so-called “math

co-processors”. Co-processors were an

inherent part of the world of the mainframes but came to be thought of as

something exotic in personal computers (PC) because there was such a focus on

the central processing unit (CPU) (8086, 68020, i486 etc) and some

co-processors (notably graphical processing units (GPU)) have assumed a

cult-like following. The evolution of

the FPU is interesting in that as manufacturing techniques improved they were

often integrated into the CPU architecture before again when the PC era began, Intel’s

early 808x & 8018x complimented by the optional 8087 FPU, the model

replicated by the 80286 & 80287 pairing, the latter continuing for some

time as the only available FPU for almost two years after the introduction of

the 80386 (later renamed i386DX in an attempt to differential genuine “Intel

Inside” silicon from the competition which had taken advantage of the

difficulties in trade-marking numbers).

The delay was due to the increasing complexity of FPU designs and flaws

were found in the early 387s.

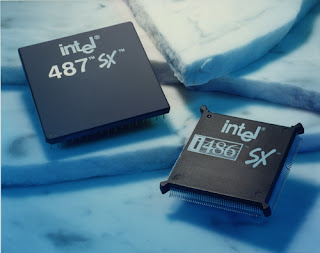

Intel i487SX & i486SX.

The management of those problems was well-managed by

Intel but with the release of the i487 in 1991 they kicked an own goal. First displayed in 1989, the i486DX had been

not only a considerable advance but included an integrated FPU (also with some

soon-corrected flaws). That was good but

to grab some of the market share from those making fast 80386DX clones, Intel

introduced the i486SX, marketed as a lower-cost chip which was said to be an

i486 with a reduced clock speed and without the FPU. For many users that made sense because anyone

doing mostly word processing or other non-number intensive tasks really had

little use for the FPU but then Intel introduced the i487SX, a FPU unit which,

in the traditional way, plugged into a socket on the system-board (as even them

motherboards were coming to be called) al la a 287 or 387. However, it transpired i487SX was functionally

almost identical to an i486DX, the only difference being that when plugged-in,

it checked to ensure the original i486SX was still on-board, the reason being

Intel wanted to ensure no market for used i486SXs (then selling new for

hundreds of dollars) emerged. To achieve

this trick, the socket for the I487 had an additional pin and it was the

presence of this which told the system board to disable the i486SX. The i487SX was not a success and Intel

suffered what was coming to be called “reputational damage”.

Dual socket system-board with installed i486SX, the vacant socket able to handle either the i486DX or the i487SX.

The i487SX affair was however a soon forgotten minor blip

in Intel’s upward path. In 1994, Intel

released the first of the Pentium CPUs all of which were sold with an

integrated FPU, establishing what would become Intel’s standard architectural

model. Like the early implementations of

the 387 & 487, there were flaws and upon becoming aware of the problem,

Intel initiated a rectification programme.

They did not however issue a recall or offer replacements to anyone who

had already purchased a flawed Pentium and, after pressure was exerted,

undertook to offer replacements only to those users who could establish their pattern

of use indicated they would actually be in some way affected. Because of the nature of the bug, that meant “relatively

few”. The angst however didn’t subside and

a comparison was made with a defect in a car which would manifest only if

speeds in excess of 125 mph (200 km/h) were sustained for prolonged periods. Although in that case only “relatively few”

might suffer the fault, nobody doubted the manufacturer would be compelled to

rectify all examples sold and such was the extent of the reputational damage

that Intel was compelled to offer what amounted to a “no questions asked”

replacement offer. The corporation’s

handing of the matter has since often been used as a case study in academic

institutions by those studying law, marketing, public relations and such.