Demand (pronounced dih-mand (U) or dee–mahnd (non-U))

(1) To ask for with proper authority; claim as a right.

(2) To ask for peremptorily or urgently.

(3) To call for or require as just, proper, or necessary.

(4) In law, to lay formal claim to.

(5) In law, to summon, as to court.

(6) An urgent or pressing requirement.

(7) In economics, the desire to purchase, coupled (hopefully) with the power to do so.

(8) In economics, the quantity of goods that buyers will take at a particular price.

(9) A requisition; a legal claim.

(10) A question or inquiry (archaic).

1250-1300: From Middle English demaunden and Anglo-French demaunder, derived from the Medieval Latin dēmandāre (to demand, later to entrust) equivalent to dē + mandāre (to commission, order). The Old French was demander and, like the English, meant “to request” whereas "to ask for as a right" emerged in the early fifteenth century from Anglo-French legal use. As used in economic theory and political economy (correlating to supply), first attested from 1776 in the writings of Adam Smith. The word demand as used by economists is a neutral term which references only the conjunction of (1) a consumer's desire to purchase goods or services and (2) hopefully the power to do so. However, in general use, to say that someone is "demanding" something does carry a connotation of anger, aggression or impatience. For this reason, during the 1970s, the language of those advocating the rights of women to secure safe, lawful abortion services changed from "abortion on demand" (ie the word used as an economist might) to "pro choice". Technical fields (notably economics) coin derived forms as they're required (counterdemand, overdemand, predemand etc). Demand is a noun & verb, demanding is a verb & adjective, demandable is an adjective, demanded is a verb and demander is a noun; the noun plural is demands.

Video on Demand (VoD)

Directed by Tiago Mesquita with a

screenplay by Mark Morgan, Among the Shadows is a thriller which straddles the

genres, elements of horror and the supernatural spliced in as required. Although in production since 2015, with the

shooting in London and Rome not completed until the next year, it wasn’t until

2018 when, at the European Film Market, held in conjunction with the Internationale Filmfestspiele Berli (Berlin

International Film Festival), that Tombstone Distribution listed it, the

distribution rights acquired by VMI, Momentum and Entertainment One, and VMI

Worldwide. In 2019, it was released

progressively on DVD and video on demand (VoD), firstly in European markets,

the UK release delayed until mid-2020.

In some markets, for reasons unknown, it was released with the title The

Shadow Within.

Video on Demand (VoD) and streaming services

are similar concepts in video content distribution but there are differences. VoD is a system which permits users to view

content at any time, these days mostly through a device connected to the

internet across IP (Internet Protocol), the selection made from a catalog or

library of available titles and despite some occasionally ambiguous messaging

in the advertising, the content is held on centralized servers and users can

choose directly to stream or download.

The VoD services is now often a sub-set of what a platform offers which

includes content which may be rented, purchased or accessed through a

subscription.

Streaming is a method of

delivering media content in a continuous flow over IP and is very much the product

of the fast connections of the twenty-first century. Packets are transmitted in real-time which

enables users to start watching or listening without waiting for an entire file

(or file set) to download, the attraction actually being it obviates the need

for local storage. There’s obviously

definitional and functional overlap and while VoD can involve streaming, not

all streaming services are technically VoD and streaming can also be used for

live events, real-time broadcasts, or continuous playback of media without

specific on-demand access. By contrast, the core purpose of VoD is to provide

access at any time and streaming is a delivery mechanism, VoD a broad concept and

streaming a specific method of real-time delivery as suited to live events as

stored content.

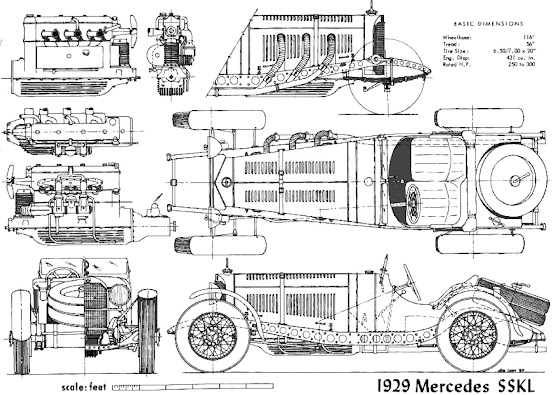

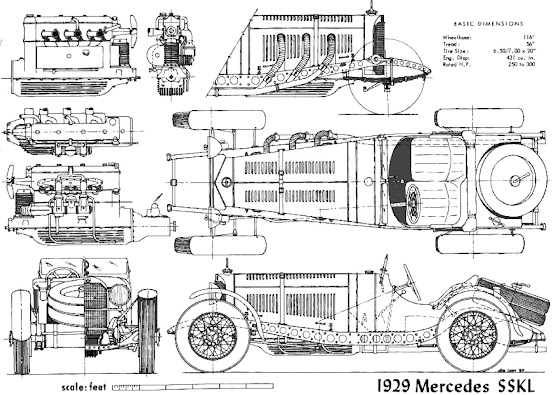

The Mercedes-Benz SSKL and the Demand Supercharger

Modern rendition of Mercedes-Benz SSLK in schematic, illustrating the drilled-out chassis rails. The title is misleading because the four or five SSKLs built were all commissioned in 1931 (although it's possible one or more used a modified chassis which had been constructed in 1929). All SSK chassis were built between 1928-1932 although the model remained in the factory's catalogue until 1933.

The Mercedes-Benz SSKL was one of the last of the road cars which could win top-line grand prix races. An evolution of the earlier S, SS and SSK, the SSKL (Super Sports Kurz (short) Leicht (light)) was notable for the extensive drilling of its chassis frame to the point where it was compared to Swiss cheese; reducing weight with no loss of strength. The SSKs and SSKLs were famous also for the banshee howl from the engine when the supercharger was running; nothing like it would be heard until the wail of the BRM V16s twenty years later. It was called a demand supercharger because, unlike some constantly-engaged forms of forced-induction, it ran only on-demand, in the upper gears, high in the rev-range, when the throttle was pushed wide-open. Although it could safely be used for barely a minute at a time, when running, engine power jumped from 240-odd horsepower (HP) to over 300. The number of SSKLs built has been debated and the factory's records are incomplete because (1) like many competition departments, it produced and modified machines "as required" and wasn't much concerned about documenting the changes and (2) many archives were lost as a result of bomb damage during World War II (1939-1945); most historians suggest there were four or five SSKLs, all completed (or modified from earlier builds) in 1931. The SSK had enjoyed great success in competition but even in its heyday was in some ways antiquated and although powerful, was very heavy, thus the expedient of the chassis-drilling intended to make it competitive for another season. Lighter (which didn't solve but at least to a degree ameliorated the brake & tyre wear) and easier to handle than the SSK (although the higher speed brought its own problems, notably in braking), the SSKL enjoyed a long Indian summer and even on tighter circuits where its bulk meant it could be out-manoeuvred, sometimes it still prevailed by virtue of durability and sheer power.

Rudolf Caracciola (1901–1959) and SSKL in the wet, German Grand Prix, Nürburgring, 19 July, 1931. Alfred Neubauer (1891–1980; racing manager of the Mercedes-Benz competition department 1926-1955) maintained Caracciola "...never really learned to drive but just felt it, the talent coming to him instinctively."

Sometimes too it got lucky. When the field assembled in 1931 for the Fünfter Großer Preis von Deutschland (fifth German Grand Prix) at the Nürburgring, even the factory acknowledged that at 1600 kg (3525 lb), the SSKLs, whatever their advantage in horsepower, stood little chance against the nimble Italian and French machines which weighed-in at some 200 KG (440 lb) less. However, on the day there was heavy rain with most of race conducted on a soaked track and the twitchy Alfa Romeos, Maseratis and the especially skittery Bugattis proved less suited to the slippery surface than the truck-like but stable SSKL, the lead built up in the rain enough to secure victory even though the margin narrowed as the surface dried and a visible racing-line emerged. Time and the competition had definitely caught up by 1932 however and it was no longer possible further to lighten the chassis or increase power so aerodynamics specialist Baron Reinhard von Koenig-Fachsenfeld (1899-1992) was called upon to design a streamlined body, the lines influenced both by his World War I (1914-1918 and then usually called the "World War") aeronautical experience and the "streamlined" racing cars which had been seen in the previous decade. At the time, the country greatly was affected by economic depression which spread around the world after the 1929 Wall Street crash, compelling Mercedes-Benz to suspend the operations of its competitions department so the one-off "streamliner" was a private effort (though with some tacit factory assistance) financed by the driver (who borrowed some of the money from his mechanic!).

The streamlined SSKL crosses the finish line, Avus, 1932.

The

driver was Manfred von Brauchitsch (1905-2003), nephew of Major General (later Generalfeldmarschall

(Field Marshal)) Walther von Brauchitsch (1881–1948; Oberbefehlshaber (Commander-in-Chief) of OKH (Oberkommando des Heeres (the German army's high command)

1938-1941). An imposing but ineffectual head of the army, Uncle Walther also borrowed

money although rather more than loaned by his nephew's mechanic, the field

marshal's funds coming from the state exchequer, "advanced"

to him by Adolf Hitler (1889-1945; Führer (leader) and German head of

government 1933-1945 & head of state 1934-1945). Quickly Hitler learned the easy way of

keeping his mostly aristocratic generals compliant was to loan them money, give

them promotions, adorn them with medals and grant them estates in the lands

he'd stolen during his many invasions.

His "loans" proved good investments. Beyond his exploits on the circuits, Manfred

von Brauchitsch's other footnote in the history of the Third Reich (1933-1945)

is the letter sent on April Fools' Day 1936 to Uncle Walther (apparently as a

courtesy between gentlemen) by Baldur von Schirach (1907-1974; head of the Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth) 1931-1940

& Gauleiter (district party leader) and Reichsstatthalter

(Governor) of Vienna 1940-1945) claiming he given a "horse whipping" to the general's nephew because a remark the racing driver was alleged to have made about Frau von Schirach (the daughter of Hitler's court photographer!). It does seem von Schirach did just that though it wasn't quite the honorable combat he'd claimed: in the usual Nazi manner he'd arrived at von Brauchitsch's apartment in the company of several thugs and, thus assisted, swung his leather whip. Von Brauchitsch denied ever making the remarks. Unlike the German treasury, the mechanic got his money back and that loan proved a good investment, coaxing from the SSKL a victory in its final fling. Crafted in aluminum by Vetter in Cannstatt, the body was mounted on von Brauchitsch's race-car and proved its worth at the at the Avusrennen (Avus race) in May 1932; with drag reduced by a quarter, the top speed increased by some 12 mph (20 km/h) and the SSKL won its last major trophy on the unique circuit which rewarded straight-line speed like no other. It was the last of the breed; subsequent grand prix cars would be pure racing machines with none of the compromises demanded for road-use.

Evolution of the front-engined Mercedes-Benz grand prix car, 1928-1954

1928 Mercedes-Benz SS.

As road cars, the Mercedes-Benz W06 S (1927-1928) & SS (1928-1930) borrowed unchanged what had long been the the standard German approach in many fields (foreign policy, military strategy, diplomacy, philosophy etc): robust engineering and brute force; sometimes this combination worked well, sometimes not. Eschewing refinements in chassis engineering or body construction as practiced by the Italians or French, what the S & SS did was achieved mostly with power and the reliability for which German machinery was already renowned. Although in tighter conditions often out-manoeuvred, on the faster circuits both were competitive and the toughness of their construction meant, especially on the rough surfaces then found on many road courses, they would outlast the nimble but

fragile opposition.

1929 Mercedes-Benz SSK.

By the late 1920s it was obvious an easier path to higher performance than increasing power was to reduce the SS's (Super Sport) size and weight. The former easily was achieved by reducing the wheelbase, creating a two-seat sports car still suitable for road and track, tighter dimensions and less bulk also reducing fuel consumption and tyre wear, both of which had plagued the big, supercharged cars. Some engine tuning and the use of lighter body components achieved the objectives and the SSK was in its era a trophy winner in sports car events and on the grand prix circuits. Confusingly, the "K" element in the name stood for kurz (short) and not kompressor (supercharger) as was applied to some other models although all SSKs used a supercharged, 7.1 litre (433 cubic inch) straight-six.

1931 Mercedes-Benz SSKL.

The French, British and Italian competition however also were improving their machinery and by late 1930, on the racetracks, the SSK was becoming something of a relic although it remained most desirable as a road car, demand quelled only by a very high price in what suddenly was a challenging economic climate. Without the funds to create anything new and with the big engine having reached the end of its development potential, physics made obvious to the engineers more speed could be attained only through a reduction in mass so not only were body components removed or lightened where possible but the chassis and sub-frames were drilled to the point where the whole apparatus was said to resemble "a Swiss cheese". The process was time consuming but effective because, cutting the SSK's 1600 KG heft to the SSKL's more svelte 1445 (3185), combined with the 300-odd HP which could be enjoyed for about a minute with the supercharger engaged, produced a Grand Prix winner which was competitive for a season longer than any had expected and one also took victory in the 1931 Mille Miglia. Although it appeared in the press as early a 1932, the "SSKL" designation is retrospective, the factory's extant records listing the machines either as "SSK" or "SSK, model 1931". No more than five were built and none survive (rumors of a frame "somewhere in Argentina" apparently an urban myth) although some SSK's were at various times "drilled out" to emulate the look and the appeal remains, a replica cobbled together from real and fabricated parts sold at auction in 2007 for over US$2 million; this was when a million dollars was still a lot of money.

1932 Mercedes-Benz SSKL (die Gurke).

The one-off bodywork (hand beaten from aircraft-grade sheet aluminum) was fabricated for a race held at Berlin's unique Automobil-Verkehrs- und Übungsstraße (Avus; the "Automobile traffic and training road") which featured two straights each some 6 miles (10 km) in length, thus the interest in increasing top speed and while never given an official designation by the factory, the crowds dubbed it die Gurke (the cucumber). The streamlined SSKL won the race and was the first Mercedes-Benz grand prix car to be called a Silberpfeil (silver arrow), the name coined by radio commentator Paul Laven (1902-1979) who was broadcasting trackside for Südwestdeutsche Rundfunkdienst AG (Southwest German Broadcasting Service); he was struck by the unusual appearance although the designer had been inspired by an aircraft fuselage rather than arrows or the vegetable of popular imagination. The moniker was more flattering than the nickname Weiße Elefanten (white elephant) applied to S & SS which was a reference to their bulk and not a use of the phrase in its usual figurative sense. The

figurative sense came from the Kingdom of Siam (modern-day Thailand) where

elephants were beasts of burden, put to work hauling logs in forests or carting

other heavy roads but the rare white (albino) elephant was a sacred animal which

could not be put to work. However, the

owner was compelled to feed and care for the unproductive creature and the

upkeep of an elephant was not cheap; they have large appetites. According to legend, if some courtier

displeased the king, he could expect the present of a white elephant. A “white elephant” is thus an unwanted

possession that though a financial burden, one is “stuck with” and the term is

applied the many expensive projects governments around the world seem unable to

resist commissioning.

Avus circuit. Unique in the world, it was the two long straights which determined

die Gurke's emphasis on top speed. Even the gearing was raised (ie a numerically lower differential ratio) because lower engine speeds were valued more than low-speed acceleration which was needed only once a lap.

The size of the S & SS was exaggerated by the unrelieved expanses of white paint (Germany's designated racing color) although despite what is sometimes claimed,

Ettore

Bugatti’s (1881–1947) famous quip “fastest trucks in the world” was his back-handed compliment not to the German cars but to W.

O. Bentley’s (1888–1971) eponymous racers which he judged brutish compared to

his svelte machines. Die Gurke ended up silver only because such had been the rush to complete the build in time for the race, there was time to apply the white paint so it raced in a raw aluminum skin. Remarkably, in full-race configuration,

die Gurke was driven to Avus on public roads, a practice which in many places was tolerated as late as the 1960s. Its job at Avus done,

die Gurke was re-purposed for high-speed tyre testing (its attributes (robust, heavy and fast) ideal for the purpose) before "disappearing" during World War II. Whether it was broken up for parts or metal re-cycling, spirted away somewhere or destroyed in a bombing raid, nobody knows although it's not impossible conventional bodywork at some point replaced the streamlined panels. In 2019, Mercedes-Benz unveiled what it described as an "exact replica" of

die Gurke, built on an original (1931) chassis.

1934 Mercedes-Benz W25.

After building the replica Gurke, Mercedes-Benz for the first time subjected it to a wind-tunnel test, finding (broadly in line with expectations) its cd (coefficient of drag) improved by about a third, recording 0.616 against a standard SSK's 0.914. By comparison, the purpose-built W25 from 1934 delivered a 0.614 showing how effective Baron Koenig-Fachsenfeld's design had been although by today's standards, the numbers are not of shapes truly "slippery". Although "pure" racing cars had for years existed, the W25 (Werknummer (works number) 25) was the one which set many elements is what would for a quarter-century in competition be the default template for most grand prix cars and its basic shape and configuration remains recognizable in the last front-engined car to win a Word Championship grand prix in 1960. The W25 was made possible by generous funding from the new Nazi Party, "prestige projects" always of interest to the propaganda-minded party. With budgets which dwarfed the competition, immediately the Mercedes-Benz and Auto Unions enjoyed success and the W25 won the newly inaugurated 1935 European Championship. Ironically, the W25's most famous race was the 1935 German Grand Prix at the Nürburgring, won by the inspired Italian Tazio Nuvolari (1892–1953) in an out-dated and under-powered Alfa-Romeo P3, von Brauchitsch's powerful W25 shredding a rear tyre on the final lap. However, the Auto Union's chassis design fundamentally was more farsighted; outstanding though the engine was, the W25's platform was, in many ways, eine bessere Gurke (a better cucumber) and because its limitations were inherent, the factory "sat out" most of the 1936 season to develop the W125.

1937 Mercedes-Benz W125.

Along with the dramatic, mid-engined, V16 Auto Union Type C, the W125 was the most charismatic race car of the "golden age" of 1930s European circuit racing. When tuned for use on the fastest circuits, the 5.7 litre (346 cubic inch) straight-eight generated over 640 HP and in grand prix racing that number would not be exceeded until the turbocharged engines (first seen in 1977) of the 1980s. The W125 used a developed version of the W25's 3.4 (205) & 4.3 (262) straight-eights and the factory had assumed this soon would be out-performed by Auto Union's V16s but so successful did the big-bore eight prove the the Mercedes-Benz V16 project was aborted, meaning resources didn't need to be devoted to the body and chassis engineering which would have been required to accommodate the bigger, wider and heavier unit (something which is subsequent decades would doom a Maserati V12 and Porsche's Flat-16. The W125 was the classic machine of the pre-war "big horsepower" era and if a car travelling at 100 mph (160 km/h) passed a W125 at standstill, the latter could accelerate and pass that car within a mile (1.6 km).

A

W125 on the banked Nordschleife

(northern ribbon (curve)) at Avus, 1937.

At Avus, the streamlined bodywork was fitted because a track which is 20

km (12 miles) in length but has only four curves puts an untypical premium on

top-speed. The banked turn was

demolished in 1967 because increased traffic volumes meant an intersection was

needed under the Funkturm (radio

tower), tower and today only fragments of the original circuit remain although

the lovely art deco race control tower still exists and was for a time used as

restaurant. Atop now sits a Mercedes-Benz

three-pointed star rather than the swastika which flew in 1937.

1938 Mercedes-Benz W154.

On the fastest circuits the streamlined versions of the W125s were geared to attain 330 km/h (205 mph) and 306 km/h (190 mph) often was attained in racing trim. With streamlined bodywork, there was also the Rekordwagen built for straight-line speed record attempts and one set a mark of 432.7 km/h (268.9 mph), a public-road world speed record that stood

until 2017. Noting the speeds and aware the cars were already too fast for circuits which had been designed for, at most, velocities sometimes 100 km/h (50 mph) less, the governing body changed the rules, limiting the displacement for supercharged machines to 3.0 litres (183 cubic inch), imagining that would slow the pace. Fast though the rule-makers were, the engineers were quicker still and it wasn't long before the V12 W154 was posting lap-times on a par with the W125 although they did knock a few km/h off the top speeds. The rule change proved as ineffective in limiting speed as the earlier 750 KG formula which had spawned the W25 & W125.

1939 Mercedes-Benz W165.

An exquisite one-off, the factory built three W165s for the single purpose of contesting the 1939 Tripoli Grand Prix. Remarkable as it may now sound, there used to be grand prix events in Libya, then a part of Italy's colonial empire. Anguished at having for years watched the once dominant Alfa Romeos enjoy only the odd (though famous) victory as the German steamroller flattened all competition (something of a

harbinger of the Wehrmacht's military successes in 1939-1940), the Italian authorities waited until the last moment before publishing the event's rules, stipulating the use of a

voiturette (small car) with a maximum displacement of 1.5 litres (92 cubic inch). The rules were designed to suit the Alfa Romeo 158 (Alfetta) and Rome was confident the Germans would have no time to assemble such a machine. However, knowing Adolf Hitler (1889-1945; Führer (leader) and German head of government 1933-1945 & head of state 1934-1945), still resenting what happened at the Nürburgring in 1935, would not be best pleased were his Axis partner (and vassal) Benito Mussolini (1883-1945;

Duce (leader) & Prime-Minister of Italy 1922-1943) to enjoy even this small victory, the factory scrambled and conjured up the V8-powered (a first for Mercedes-Benz) W165, the trio delivering a "

trademark 1-2-3" finish in Tripoli. As a consolation, with Mercedes-Benz busy building inverted V12s for the Luftwaffe's Messerschmitts, Heinkels and such, an Alfa Romeo won the 1940 Tripoli Grand Prix which would prove the city's last.

1954 Mercedes Benz W196R Strómlinienwagen (literally "streamlined car" but translated usually as "Streamliner".

A curious mix of old (drum brakes, straight-eight engine and swing axles) and new (a

desmodromic valve train, fuel injection and aerodynamics developed in a wind-tunnel with the help of engineers then banned from being involved in aviation), the intricacies beneath the skin variously bemused or delighted those who later would come to be called nerds but it was the sensuous curves which attracted most publicity. Strange though it appeared, it was within the rules and clearly helped deliver stunning speed although the pace did expose some early frailty in road-holding (engineers have since concluded the thing was a generation ahead of tyre technology). It was one of the prettiest grand prix cars of the post war years and the shape (sometimes called "type Monza", a reference to the Italian circuit with long straights so suited to it) would later much appeal to pop-artist Andy Warhol (1928–1987) who used it in a number of prints.

1954 Mercedes-Benz W196R. In an indication of how progress accelerated after 1960, compare this W196R with (1) the W25 of 20 years earlier and (2) any grand prix car from 1974, 20 years later.

However, although pleasing to the eye, the W196R Strómlinienwagen was challenging even for expert drivers and it really was a machine which deserved a de Dion rear suspension rather than the swing axles (on road cars the factory was still building a handful with these as late as 1981 and their fudge of semi-trailing rear arms (the "swing axle when you're not having a swing axle") lasted even longer). Of more immediate concern to the drivers than any sudden transition to oversteer was that the aluminium skin meant they couldn't see the front wheels so, from their location in the cockpit, it was difficult to judge the position of the extremities, vital in a sport where margins can be fractions of a inch. After the cars in 1954 returned to Stuttgart having clouted empty oil drums (those and bails of hay was how circuity safety was then done) during an unsuccessful outing to the British Grand Prix at Silverstone, a conventional body quickly was crafted and although visually unremarkable, the drivers found it easier to manage and henceforth, the Strómlinienwagen appeared only at Monza. There was in 1954-1955 no constructor's championship but had there been the W196R would in both years have won and it delivered two successive world driver's championships for Juan Manuel Fangio (1911–1995). Because of rule changes, the three victories by the W196R Strómlinienwagen remain the only ones in the Formula One World Championship (since 1950) by a car with enveloping bodywork.