Bugeye (pronounced buhg-ahy)

(1)

A nautical term for a ketch-rigged sailing vessel used on Chesapeake Bay.

(2)

A slang term, unrelated to the nautical use, used to describe objects or

creatures with the bulging eyes resembling those of certain bugs.

1883: An Americanism, the construct being bug + eye, coined to describe the 1880s practice of shipwrights painting a large eye on each bow of the ketches used for oyster dredging in Chesapeake Bay, an estuary in the US states of Maryland and Virginia. Bug dates from 1615–1625 and the original use was to describe insects, apparently as a variant of the earlier bugge (beetle), thought to be an alteration of the Middle English budde, from the Old English -budda (beetle) but etymologists are divided on whether the phrase “bug off” (please leave) is related to the undesired presence of insects or was of a distinct origin. Although “unbug” makes structural sense (ie remove a bug, as opposed to the sense of “debug”), it doesn’t exist whereas forms such as the adjectives unbugged (not bugged) and unbuggable (not able to be bugged) are regarded as standard. Eye pre-dates 900 and was from the Middle English eie, yë, eighe, eyghe, yȝe, eyȝe & ie, from the Old English ēge, a variant of ēage, from the Proto-West Germanic augā, from the Proto-Germanic augô (eye). It was cognate with the German Auge & the Icelandic auga and akin to the Latin oculus (eye), the Lithuanian akìs (eye), the Slavic (Polish) oko (eye), the Old Church Slavonic око (oko) (eye), the Albanian sy (eye), the Ancient Greek ὄψ (óps) (in poetic use, “eye; face”) & ὄσσε (ósse) (eyes), the Armenian ակն (akn), the Avestan aši (eyes) and the Sanskrit अक्षि (ákṣi). A related Modern English form is “ogle”. Bugeye is a noun and bugeyed is an adjective; the noun plural is bugeyes. Hyphenated use of all forms is common.

Frogeye (pronounced frog-ahy or frawg-ahy)

(1)

In botany, a small, whitish leaf spot with a narrow barker border, produced by

certain fungi.

(2)

A plant disease so characterized.

(3)

A slang term, unrelated to the botanical use, used to describe objects or

creatures with the bulging eyes resembling those of frogs.

1914–15: A descriptive general term, the construct being frog + eye, for the condition Botryosphaeria obtusa, a plant pathogen that causes Frogeye leaf spot, black rot and cankers on many plant species. The fungus was first described by in 1832 as Sphaeria obtusa, refined as Physalospora obtusa in 1892 while the final classification was defined in 1964. Frog (any of a class of small tailless amphibians of the family Ranidae (order Anura) which typically move by hopping and in zoology often referred to as “true frog” because in general use “frog” is used loosely or visually similar creatures) pre-dates 1000 and was from the Middle English frogge, from the Old English frogga, from the Proto-West Germanic froggō (frog). It was cognate with the Norwegian Nynorsk fraug (frog) and Old Norse frauki and there may be links with the Saterland Frisian Poage (frog) and the German Low German Pogg & Pogge (frog). The alternative forms in English (some still in regional use at least as late as the mid-seventeenth century were frosk, frosh & frock. Eye pre-dates 900 and was from the Middle English eie, yë, eighe, eyghe, yȝe, eyȝe & ie, from the Old English ēge, a variant of ēage, from the Proto-West Germanic augā, from the Proto-Germanic augô (eye). It was cognate with the German Auge & the Icelandic auga and akin to the Latin oculus (eye), the Lithuanian akìs (eye), the Slavic (Polish) oko (eye), the Old Church Slavonic око (oko) (eye), the Albanian sy (eye), the Ancient Greek ὄψ (óps) (in poetic use, “eye; face”) & ὄσσε (ósse) (eyes), the Armenian ակն (akn), the Avestan aši (eyes) and the Sanskrit अक्षि (ákṣi). A related Modern English form is “ogle”. Frogeye is a noun and frogeyed is an adjective; the noun plural is frogeyes. Hyphenated use of all forms is common.

Bugeye or frogeye: The Austin-Healey Sprite

1960 Austin-Healey Sprite (left) & 1972 MG Midget (right).

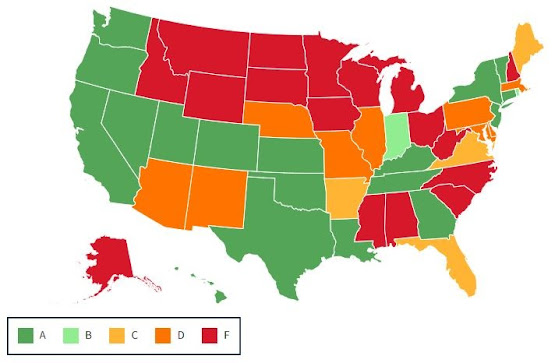

The Austin-Healey Sprite was produced between 1958 and 1971 (although in the last year of production they were badged as the Austin Sprite, reflecting the end of the twenty year contract with Donald Healey's (1898–1988) eponymous company). Beginning in 1961, the car was restyled and a more conventional frontal appearance was adopted, shared with the almost identical MG Midget, introduced as at the same time as a corporate companion and the Midget outlived the Sprite, the last built in 1980. Upon release, the Sprite immediately picked up the nicknames frogeye (UK & most of the Commonwealth) and bugeye (North America) because the headlights were mounted as protuberances atop the hood (bonnet), bearing a resemblance to the eyes of some frogs and bugs. The original design included retractable headlights but to reduce both cost and weight, fixed-lights were used. As purely functional mountings, such things continue to be fitted to rally-cars. The linguistic quirk that saw the Sprite nicknamed bugeye in North America and frogeye in most of the rest of the English-speaking world is a mystery. Etymologists have noted the prior US use of bugeye as a nautical term but it was both geographically and demographically specific and that use, visually, was hardly analogous with the Sprite. No other explanation has been offered; the English language is like that.

1963 Lightburn Zeta (left) 1964 Lightburn Zeta Sports (centre) & Lightburn Zeta Sports with "sports lights" (right).

1949 Crosley Hotshot.

Although distinctive, the look wasn’t new, familiar from the use of the Triumph TR2 (1952) and Crosley in the US had used a similar arrangement for their "Hotshot" & "Super Sport" (1949-1952 and notable for being fitted with four-wheel disk brakes) and in Australia, Lightburn (previously noted for their well-regarded washing machines and cement mixers) were in 1964 forced to adopt them for the woeful Zeta Sports to meet headlight-height regulations. The Zeta Sports was better looking than the Trabant-like "two-door sedan" which preceded it but truly that is damning with faint praise. An adaptation (development seems not the appropriate word) of the Meadows Frisky microcar of the mid-1950s, the Zeta Sports was built in South Australia and it wasn't initially realized that headlight-height rules in New South Wales (NSW) were such that the low-slung Zeta couldn't comply, even were the suspension to be raised, an expedient MG was compelled to use in 1974 to ensure the bumpers of the Midget & MGB sat at the height specified in new US rules. Instead "sports lights" were added to the bonnet (hood) which lent some more cartoon-like absurdity to the thing but did little to increase its appeal, only a few dozen built in the two years it was available.

1959 Alfa Romeo Giulietta Sprint Speciale, Tipo (type) 101.20.

Ungainly the bugeye lights may have been but they were a potentially handy addition given the original headlights doubled as bumper bars. That seems a silly idea and it is but it wasn't unique to the Zeta and some examples had exquisite (if vulnerable) coachwork, such as the early (low-nose) versions of the much-admired Alfa Romeo Giulietta SS (Sprint Speciale, Tipo (type) 101.20; 1957-1962). It was only the first 101 cars which were produced in lightweight, bumper-bar less form, that run to fulfil the FIA's homologation rules which demanded a minimum of 100 identical examples to establish eligibility in certain classes of production-car racing.

Lindsay Lohan in "bugeye" sunglasses, the look made popular by Jacqueline Kennedy (1929-1994; US First Lady 1961-1963).

So aerodynamically efficient (the drag coefficient (CD) a reputed .28) was Carrozzeria Bertone's design that although using only a 1290 cm3 (79 cubic inch) engine with barely 100 hp (75 kW), the SS could achieve an even now impressive 200 km/h (124 mph). Fitted with a 498 cm3 engine which yielded 21 hp (15.5 kW), the Zeta Sedan thankfully wasn't that fast but did feature a four speed manual gearbox with no reverse gear; to reverse a Zeta, the ignition key was turned the opposite direction so the crankshaft turned the other way. All four gears remained available so top speed in reverse would presumably have been about the same as going forward but, as Chrysler discovered during the testing for the doomed Airflow (1934-1937), given the vagaries of aerodynamics, it may even have been faster, something which certainly may have been true of the Sports, (at least with the soft top erected) given the additional drag induced by the bugeye lights. This was never subject to a practical test because unlike the sedan, the diminutive roadster had a reverse gear.

The class-winning Austin-Healey Sprite, Coupe des Alpes rally, 1958. With its goofy bugeyes and "grinning grill", the Sprite was often anthropomorphized. It was part of the little machine's charm and, cheap to run and easy to tune, Sprites were for decades a mainstay of entry-level motorsport and still appear in historic categories.

The French bugeye: The Matra 530SX

Matra’s 1967 advertising copy for the last of the Sports Jets (left) and a 530 (right).

René

Bonnet (1904–1983) was a self-taught French designer and engineer who joined the

long list of those unable to resist the lure of building a car bearing his

name. It ended badly but his venture

does enjoy a place in history because briefly he produced the first mid-engined

road cars offered for general sale, some four years after the configuration had

in Formula One racing begun to exert a dominance which endures to this day. His diminutive sports car (marketed

variously as René Bonnet Djet, Matra-Bonnet Djet, Matra Sports Djet & Matra

Sports Jet) were produced by his company between 1962-1964 and by Matra for a

further two years, the French manufacturer taking over the concern when Bonnet

was unable to pay for the components earlier supplied. While Matra continued production of the Djet,

it used the underpinnings for a much revised model which would in 1967 emerge

as the Matra 530.

Matra R.530 surface to air missile (1962, left) and René Bonnet Missile (1959-1962).

It

was only force of circumstances which would lead Matra to producing the

Djet. As Bonnet’s largest creditor when

the bills grew beyond his capacity to pay, the accountants worked out the only

hope of recovering their stake was to take the equity and continue the

operation. Although asset-stripping wasn’t

then the thing it would later become, there’s nothing to suggest this was

contemplated and the feeling was the superior administrative capacity of Matra

would allow things to be run in a more business-like manner although there was

genuine interest in the workforce’s skills with the then still novel fibreglass. However, although Djet production resumed

under new management, Bonnet’s other offerings such as the Missile (1959-1962) were

retired. The missile, a small,

front-wheel drive (FWD) convertible was a tourer in the pre-war vein rather

than a sports car but while the idea probably had potential, the price was high,

the performance lethargic and the styling quirky even by French standards. In looks, it had much in common with the

contemporary Daimler SP250 including the tailfins and catfish-like nose but

while the British roadster was genuinely a high-high performance (if flawed) sports

car, the missile did not live up to its name; under the hood (bonnet) sat small

(some sub 1000 cm3) four cylinder engines rather than the Daimler’s sonorous

V8. One influence did however carry over:

Matra named the 530 after one of their other products: the R.530 surface to air

missile which had entered service in 1962 after a five year development.

Matra 530: The LX (left) and the SX (right).

Using three-numeral numbers for car names is not unusual but usually the reference is to engine capacity (in the metric world a 280 being 2.8 litres, a 350, 3.5 litres etc while in imperial terms 350, 427 et al stood as an indication of the displacement in cubic inches). Buick used 225 in honor of the impressive 225 inch (5.7 m) length of the the 1959 Electra, sticking to to it for years even as the thing grew and shrunk and there have been many three-digit numbers which indicated a model's place in the hierarchy, the choice sometimes seemingly arbitrary. Nor is a link with the materiel of the military unusual, the names of warships have been borrowed and Chevrolet used Corvette as a deliberate allusion to speed and agility but an air-to-air missile was an unusual source although Dodge did once display a Sidewinder show car. At the time though, it wasn't the Matra's name which attracted most comment. There

have been a few French cars which looked weirder than the 530 but the

small, mid-engined sports car was visually strange enough although, almost

sixty years on, it has aged rather well and the appearance would by most

plausibly be accepted as something decades younger. The automotive venture wasn’t a risk for

Matra because it was a large and diversified industrial conglomerate with

profitable interests in transport, telecommunications, aerospace and of course defence

(missiles, cluster-bombs, rockets and all that). As things transpired, the automotive division

would for a while prove a valuable prestige project, the participation in

motorsport yielding a Formula One Constructors’ Championship and three back-to-back

victories in the Le Mans 24 hour endurance classic.

Matra 530: The LX (left) and the SX (right).

The

road-car business however proved challenging and Matra never became a major

player. Although the British and

Italians would prove there was a market for small, economical sports cars,

buyers seemed mostly to prefer more traditionally engineered roadsters which were

ruggedly handsome rather than delicately avant-garde. Although as a niche model in a niche market,

the volumes were never high, the 530 was subject to constant development and in

1970 the 530LX was released, distinguished by detail changes and some

mechanical improvements. Most distinctive

however was next year’s 530SX, an exercise in “de-contenting” (producing what

the US industry used to call a “stripper”) so it could be offered at a lower

price point, advertised at 19,000 Fr against the 22,695 asked for the LX. It was a linguistic coincidence the SX label was

later chosen for the lower price 386 & 486 CPUs (central processing unit)

by the US-based Intel although they labelled their full-priced offerings DX.

Yuri Gagarin (1934–1968; Soviet pilot and cosmonaut and the first human to travel to “outer space”) with his 1965 Matra Djet (left), standing in front of the Покори́телям ко́смоса (Monumént Pokorítelyam kósmosa) (Monument to the Conquerors of Space), the titanium obelisk erected in 1964 to celebrate the USSR's pioneering achievements in space exploration. The structure stands 351 feet (107 metres) tall and assumes an incline of 77° which is a bit of artistic licence because the rockets were launched in a vertical path but it was a good decision however because it lent the monument a greater sense of drama. Underneath the obelisk sits the Музей космонавтики (Memorial Museum of Cosmonautics (known also as the Memorial Museum of Astronautics or Memorial Museum of Space Exploration)) and in the way which was typical of projects in the Brezhnev-era (Leonid Brezhnev (1906–1982; Soviet leader 1964-1982) USSR, although construction was begun in 1964, it wasn't until 1981 the museum opened to the public.

The reduction in the cost of production of the SX was achieved in the usual way: remove whatever expensive stuff can be removed. Thus (1) the retractable headlights were replaced with four fixed “bugeyes”, a single engine air vent was fitted instead of the LX’s four, (3) the rear seat and carpet were deleted, (4) the front seats were non-adjustable, (5) the trimmed dashboard was replaced by one in brushed aluminium (which was actually much-admired), the removable targa panels in the roof were substituted with a solid panel and, (7) metal parts like bumpers and the grille were painted matte black rather than being chromed. In the the spirit of the ancien regime, the Frensh adopted the nicknames La Matra de Seigneur (the Matra of a Lord) for the LX & La Matra Pirate (the Matra of a pirate) for the SX.

Who wore the bugeye best? Austin-Healey Sprite (1958, left), Lightburn Zeta Sports (1964, centre) and Matra 530SX (1971, right).

The SX did little to boost sales and even in 1972 which proved the 530’s most prolific year with 2159 produced, buyers still preferred the more expensive model by 1299 to 860. Between 1967-1973, only 9609 530s were made: 3732 of the early models, 4731 of the LX and 1146 of the bugeyed SX and, innovative, influential and intriguing as it and the Djet were, it was a failure compared with something unadventurous like the MGB (1963-1980), over a half-million of which were delivered. One 530 however remains especially memorable, a harlequinesque 1968 model painted by French artist Sonia Delaunay (1885–1979), a founder of the school of Orphism (a fork of Cubism which usually is described as an exercise in pure abstraction rendered in vivid colors). The work was commissioned by Matra's CEO Jean-Luc Lagardère (1928–2003) for a charity auction and still is sometimes displayed in galleries. In 2003, after some thirty years of co-production with larger manufacturers, Matra’s automotive division was declared bankrupt and liquidated.