Reich (pronounced rahyk or rahykh (German))

(1) With reference to Germany or other Germanic agglomerations,

empire; realm; nation.

(2) The German state, especially (as Third Reich) during the Nazi period.

(3) A term used (loosely) of (1) hypothetical resurrections of Nazi Germany or similar states and (2) (constitutionally incorrectly), the so-called “Dönitz government (or administration)” which existed for some three weeks after Hitler’s suicide.

(4) Humorously (hopefully), a reference to a suburb, town etc with a population in which German influence or names of German origin are prominent; used also by university students when referring to departments of German literature, German history etc.

(5) As a slur, any empire-like structure, especially one that is imperialist, tyrannical, racist, militarist, authoritarian, despotic etc.

1871: From the German Reich

(kingdom, realm, state), from the Middle High German rīche, from the Old High German rīhhi

(rich, mighty; realm), from the Proto-West Germanic rīkī, from the Proto-Germanic rīkijaz

& rikja (rule), a derivative of rīks (king, ruler), from the Proto-Celtic

rīxs and thus related to the Irish rí.

The influences were (1) the primitive Indo-European hereǵ- (to rule), from which is

derived also the Latin rēx and (2)

the primitive Indo-European root reg (move in a straight line) with derivatives meaning "to

direct in a straight line", thus "to lead, rule". Cognates include the Old Norse riki, the Danish rige & rig, the Dutch

rike & rijk, the Old English rice

& rich, the Old Frisian rike, the Icelandic ríkur, the Swedish rik, the

Gothic reiki, the Don Ringe and the Plautdietsch rikj.

Reich was first used in English circa 1871 to describe the essentially Prussian creation that was the German Empire which was the a unification of the central European Germanic entities. It was never intended to include Austria because (1) Otto von Bismarck's (1815-1989; Chancellor of the German Empire 1871-1890) intricate series of inter-locking treaties worked better with Austria as an independent state and (2) he didn't regard them as "sufficiently German" (by which he would have meant "Prussian": Bismarck described Bavarians as "halfway between Austrians and human beings". At the time, the German Empire was sometimes described simply as “the Reich” with no suggestion of any sense of succession to the Holy Roman Empire. “Third Reich” was an invention of Nazi propaganda to “invent” the idea of Adolf Hitler (1889-1945; Führer (leader) and German head of government 1933-1945 & head of state 1934-1945) as the inheritor of the mantle of Charlemagne (748–814; (retrospectively) the first Holy Roman Emperor 800-814) and Bismarck. The word soon captured the imagination of the British Foreign Office, German “Reichism” coming to be viewed as much a threat as anything French had ever been to the long-time British foreign policy of (1) maintaining a balance of power in a Europe in which no one state was dominant ("hegemonic" the later term) and (2) avoid British involvement in land-conflicts on "the continent".

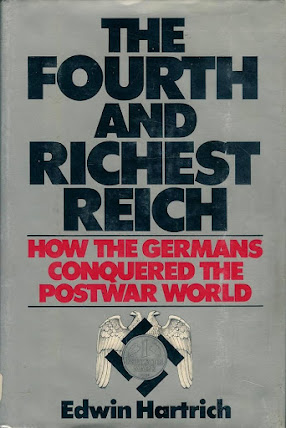

Hartrich’s thesis was a particular deconstruction of the Wirtschaftswunder (economic miracle), the unexpectedly rapid growth of the economy of the FRG (the Federal Republic of Germany, the old West Germany) in the 1950s and 1960s which produced an unprecedented and widespread prosperity. There were many inter-acting factors at play during the post-war era but what couldn’t be denied was the performance of the FRG’s economy and Hartrich attributed it to the framework of what came to be called the Marktwirt-schaft market economy with a social conscience), a concept promoted by Professor Ludwig Erhard (1897–1977) while working as a consultant to the Allied occupying forces in the immediate aftermath of the war. When the FDR was created in 1949, he entered politics, serving as economy minister until 1963 when he became Chancellor (prime-minister). His time as tenure was troubled (he was more technocrat than politician) but soziale Marktwirtschaft survived his political demise and it continues to underpin the economic model of the modern German state.

Hartrich was a neo-liberal, then a breed just beginning to exert its influence in the Western world, but he also understood that the introduction of untrammelled capitalism to Europe was likely to sow the seeds of its own destruction but he insists the “restoration” of the “…profit motive as the prime mover in German life was a fundamental step…” to economic prosperity and social stability. Of course the unique circumstances of the time (the introduction of the Deutsche Mark which enjoyed stability under the Bretton Woods system (1944), the outbreak of the Cold War, the recapitalization of industry and the provision of new plant & equipment with which to produce goods to be sold into world markets under the GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs & Trade (1947)) produced conditions which demand attention but the phenomenal growth can’t be denied. Nor was it denied at the time; within the FRG, even the socialist parties by 1959 agreed to build their platform around “consumer socialism”, a concession Hartrich wryly labelled “capitalism's finest hour”. The Fourth and Richest Reich was not a piece of economic analysis by an objective analyst and nor did it much dwell on the domestic terrorism which came in the wake of the Wirtschaftswunder, the Baader-Meinhof Group (the Red Army Faction (RAF)) and its ilk discussed as an afterthought in a few pages in an epilogue which included the bizarre suggestion Helmut Schmidt (1918–2015; FRG Chancellor 1974–1982) should be thought a latter-day Bismarck; more than one reviewer couldn’t resist mentioning Hitler himself had once accorded the same honor to the inept Joachim von Ribbentrop (1893–1946; Nazi foreign minister 1938-1945).

The word "Reich" does sometimes confuse non-specialists who equate it with the German state, probably because the Third Reich does cast such a long shadow. Murdoch journalist Samantha Maiden (b 1972) in a piece discussing references made to the Nazis (rarely a good idea except between consenting experts in the privacy of someone don's study) by a candidate in the 2022 Australian general election wrote:

The history of the nation-state known as the German Reich is commonly divided into three periods: German Empire (1871–1918) Weimar Republic (1918–1933) Nazi Germany (1933–1945).

It's an understandable mistake and the history of the German Reich is commonly divided into three periods but that doesn't include the Weimar Republic. The point about what the British Foreign Office labelled "Reichism" was exactly what the Weimar Republic (1918-1933) as a "normal" democratic state, was not. The Reich's three epochs (and there's some retrospectivity in both nomenclature and history) were the Holy Roman Empire (1800-1806), Bismarck's (essentially Prussian) German Empire (1871-1918) & the Nazi Third Reich (1933-1945).

The First Reich: the Holy Roman Empire, 800-1806

The

Holy Roman Empire was a multi-ethnic complex of territories in central Europe

that developed during the early Middle Ages, the popular identification with

Germany because the empire’s largest territory after 962 was the Kingdom of

Germany. On 25 December 800, Pope Leo

III (circa 760-816; pope 795-816) crowned Charlemagne (747–814; King of the

Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and Emperor of the Romans (and

thus retrospectively Holy Roman Emperor) from 800)) as Emperor, reviving the

title more than three centuries after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Despite the way much history has been

written, it wasn’t until the fifteenth century that “Holy Roman Empire” became

a commonly used phrase.

Leo III, involved in sometimes violent disputes

with Romans who much preferred both his predecessor and the Byzantine Empress in

Constantinople, had his own reasons for wishing to crown Charlemagne as Emperor

although it was a choice which would have consequences for hundreds of

years. According to legend, Leo ambushed

Charlemagne at Mass on Christmas day, 800 by placing the crown on his head as

he knelt at the altar to pray, declaring him Imperator Romanorum (Emperor of the Romans), in one stroke claiming

staking the papal right to choose emperors, guaranteeing his personal protection

and rejecting any assertion of imperial authority by anyone in Constantinople. Charlemagne may or may not have been aware of

what was to happen but much scholarship suggests he was well aware he was there

for a coronation but that he intended to take the crown in his own hands and

place it on his head himself. The

implications of the pope’s “trick” he immediately understood but, what’s done

is done and can’t be undone and the lesson passed down the years, Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821; leader of the French Republic 1799-1804 & Emperor of the French from 1804-1814 & 1815) not repeating the error at his coronation as French Emperor

in 1804.

Some historians prefer to date the empire from 962 when Otto I was crowned because continuous existence there began but, scholars generally concur, it’s possible to trace from Charlemagne an evolution of the institutions and principles constituting the empire, describing a gradual assumption of the imperial title and role. Not all were, at the time, impressed. Voltaire sardonically recorded one of his memorable bon mots, noting the “…agglomeration which was called and which still calls itself the Holy Roman Empire was in no way holy, nor Roman, nor an empire." The last Holy Roman Emperor, Francis II (1768–1835; Holy Roman Emperor 1792-1806) dissolved the empire on 6 August 1806, after Napoleon's creation of the Confederation of the Rhine.

The Second Reich: the Prussian Hohenzollern dynasty, 1871-1918

German Empire, 1914.

The German Empire existed from the unification of Germany in 1871 until the abdication of Wilhelm II (1859–1941; German Kaiser (Emperor) & King of Prussia 1888-1918) in 1918, when Germany became a federal republic, remembered as the Weimar Republic (1918-1933). The German Empire consisted of 26 constituent territories, most ruled by royal families. Although Prussia became one of several kingdoms in the new realm, it contained most of its population and territory and certainly the greatest military power and the one which exercised great influence within the state; a joke at the time was that most countries had an army whereas the Prussian Army had a country.

To a great extent, the Second Reich was the creation of Prince Otto von Bismarck (1815–1898; chancellor of the North German Confederation 1867-1871 and of the German Empire 1871-1890), the politician who dominated European politics in the late nineteenth although his time in office does need to be viewed through sources other than his own memoirs. After Wilhelm II dismissed Bismarck, without his restraining hand, the empire embarked on a bellicose new course that led ultimately to World War I (1914-1918), Germany’s defeat and the end the reign of the House of Hohenzollern and it was that conflict which wrote finis to the dynastic rule of centuries also of the Romanovs in Russia, the Habsburgs in Austria-Hungary and the Ottomans in Constantinople. Following the Kaiser’s abdication, the empire collapsed in the November 1918 revolution and the Weimar Republic which followed, though not the axiomatically doomed thing many seem now to assume, was for much of its existence beset by political and economic turmoil.

The Third Reich: the Nazi dictatorship 1933-1945

Nazi occupied Europe, 1942.

“Nazi Germany” is in English the common name for the period of Nazi rule, 1933-1945. The first known use of the term “Third Reich” was by German cultural historian Moeller van den Bruck (1876-1925) in his 1923 book Das Dritte Reich (The Third Reich). Van den Bruck, a devotee of Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) and a pan-German nationalist, wrote not of a defined geographical entity or precise constitutional arrangement. His work instead explored a conceptualized (if imprecisely described) and idealized state of existence for Germans everywhere, one that would (eventually) fully realize what the First Reich might have evolved into had not mistakes been made, the Second Reich a cul-de-sac rendered impure by the same democratic and liberal ideologies which would doom the Weimar Republic. Both these, van den Bruck dismissed as stepping stones on the path to an ideal; Germans do seem unusually susceptible to being seduced by ideals.

In the difficult conditions which prevailed in Germany at the time of the book’s publication, it didn’t reach a wide audience, the inaccessibility of his text not suitable for a general readership but, calling for a synthesis of the particularly Prussian traditions of socialism and nationalism and the leadership of a Übermensch (a idea from Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883) which describes a kind of idealized man who probably can come into existence only when a society is worthy of him), his work had obvious appeal to the Nazis. It was said to have been influential in the embryonic Nazi Party but there’s little to suggest it contributed much beyond an appeal to the purity of race and the idea of the “leader” (Führer) principle, notions already well established in German nationalist traditions. The style alone might have accounted for this, Das Dritte Reich not an easy read, a trait shared by the dreary and repetitive stuff written by the party “philosopher” Alfred Rosenberg (1893-1946). After Rosenberg was convicted on all four counts (planning aggressive war, waging aggressive war, war crimes & crimes against humanity) by the IMT (International Military Tribunal) at the first Nuremberg Trial (1945-1946) and sentenced to death by hanging, a joke circulated among the assembled journalists that it would have been fair to add a conviction for “crimes against literature”, a variation on the opinion his fellow defendant Baldur von Schirach (1907-1974; head of the Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth) 1931-1940 & Gauleiter (district party leader) and Reichsstatthalter (Governor) of Vienna (1940-1945) should also have been indicted for “crimes against poetry”. Von Schirach though avoided the hangman's noose he deserved.

A book channeling Nietzsche wasn’t much help for practical politicians needing manifestos, pamphlets and appealing slogans and the only living politician who attracted some approbation from van den Bruck was Benito Mussolini (1883-1945; Duce (leader) & prime minister of Italy 1922-1943). The admiration certainly didn’t extend to Hitler; unimpressed by his staging of the Munich Beer Hall Putsch (8–9 November 1923), van den Bruck dismissed the future Führer with a unusually brief deconstruction, the sentiment of which was later better expressed by another disillusioned follower: “that ridiculous corporal”. The term “Third Reich” did however briefly enter the Nazi’s propaganda lexicon and William L Shirer (1904–1993) in his landmark The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1960) reported that in the 1932 campaign for the presidency, Hitler in a speech at Berlins's Lustgarten (a place which, again perhaps disappointing some, translates as “pleasure garden”) used the slogan: “In the Third Reich every German girl will find a husband”. Shirer's book is now dated and some of his conceptual framework has always attracted criticism but it remains a vivid account of the regime's early years, written by an observer who actually was there.

The official name of the state was Deutsches Reich (German Empire) between 1933-1943 and Großdeutsches Reich (Greater German Empire) between 1943 to 1945 but so much of fascism was fake and depended for its effect on spectacle so the Nazis were attracted to the notion of claiming to be the successor of a German Empire with a thousand year history, their own vision of the Nazi state being millennialist. After they seized power, the term “Third Reich” occasionally would be invoked and, more curiously, the Nazis for a while even referred to the Weimar Republic as the Zwischenreich (Interim Reich) but as the 1930s unfolded as an almost unbroken series of foreign policy triumphs for Hitler, emphasis soon switched to the present and the future, the pre-Beer Hall Putsch history no longer needed. It was only after 1945 that the use of “Third Reich” became almost universal although the earlier empires still are almost never spoken of in that way, even in academic circles.

Van den Bruck had anyway been not optimistic and his gloominess proved prescient although his people did chose to walk (to destruction) the path he thought they may fear to tread. In the introduction to Das Dritte Reich he wrote: “The thought of a Third Empire might well be the most fatal of all the illusions to which they have ever yielded; it would be thoroughly German if they contented themselves with day-dreaming about it. Germany might perish of her Third Empire dream.” He didn’t live to see the rise and fall of the Third Reich, taking his own life in 1925, a fate probably not unknown among those who read Nietzsche at too impressionable an age and never quite recover.

Wilhelm Reich, Hawkwind and the Orgone Accumulator

Wilhelm Reich (1897-1957) was a US-based, Austrian psychoanalyst with a troubled past who believed sexual repression was the root cause of many social problems. Some of his many books widely were read within the profession but there was criticism of his tendency towards mono-causality in his analysis, an opinion shared by Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) in his comments about Reich’s 1927 book Die Funktion des Orgasmus (The Function of the Orgasm), a work the author had dedicated to his fellow Austrian. Freud sent a note of thanks for the personally dedicated copy he’d been sent as a birthday present but, brief and not as effusive in praise Reich as had expected, it was not well-received. Reich died in prison while serving a sentence imposed for violating an injunction issued to prevent the distribution of a machine he’d invented: the orgone accumulator.

The orgone accumulator was an apparently phoney device but one which inspired members of the science fiction (SF) flavored band Hawkwind to write the song Orgone Accumulator which, unusually, was first released on a live recording, Space Ritual, a 1973 double album containing material from their concerts in 1972. Something of a niche player in the world of 1970s popular music Hawkwind, perhaps improbably, proved more enduring than many, their combination of styles attracting a cult following which endures to this day.

%20Eclipse%20of%20the%20Sun,%201926.jpg)