Strumpet (pronounced struhm-pit)

A woman of loose virtue (archaic).

1300–1350: From the Middle English strumpet and its variations, strompet & strumpet (harlot; bold, lascivious woman) of uncertain origin. Some etymologists suggest a connection with

the Latin stuprata, the feminine past

participle of stuprare (have illicit

sexual relations with) from stupere,

present active infinitive of stupeo, (violation)

or stuprare (to violate) or the Late

Latin stuprum, (genitive stuprī) (dishonor, disgrace, shame, violation,

defilement, debauchery, lewdness). The

meanings in Latin and the word structure certainly appears compelling but there

is no documentary evidence and others ponder a relationship with the Middle

Dutch strompe (a stocking (as the verbal

shorthand for a prostitute)) or strompen

(to stride, to stalk (in the sense suggestive of the manner in which a prostitute

might approach a customer). Again, it’s entirely

speculative and the spelling streppett

(in same sense) was noted in the 1450s. In

the late eighteen century, strumpet came to be abbreviated as strum and also

used as a verb, which meant lexicographers could amuse themselves with wording

the juxtaposition of strum’s definitions, Francis Grose (circa 1730-1791) in

his A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar

Tongue (1785) settling on (1) to have carnal knowledge of a woman & (2)

to play badly on the harpsichord or any other stringed instrument. As a term in musical performance, strum is now merely descriptive.

Even

before the twentieth century, among those seeking to disparage women (and there

are usually a few), strumpet had fallen from favour and by the 1920s was thought

archaic to the point where it was little used except as a device by authors of historical

fiction. Depending on the emphasis it

was wished to impart, the preferred substitutes which ebbed and flowed in

popularity over the years included tramp, harlot, hussy, jezebel (sometimes

capitalized), jade, tart, slut, minx, wench, trollop, hooker, whore, bimbo, floozie

(or floozy) and (less commonly) slattern skeezer & malkin.

There’s

something about trollop which is hard to resist but it has fallen victim to modern

standards and it now can’t be flung even at white, hetrosexual Christian males

(a usually unprotected species) because of the historic association. Again the origin is obscure with most

etymologists concluding it was connected with the Middle English trollen (to go about, stroll, roll from

side to side). It was used as a synonym

for strumpet but often with the particular connotation of some debasement of

class or social standing (the the speculated link with trollen in the sense of “moving to the other (bad) side”) so a

trollop was a “fallen woman”. Otherwise

it described (1) a woman of a vulgar and discourteous disposition or (2) to act

in a sluggish or slovenly manner. North

of the border it tended to the neutral, in Scotland meaning to dangle soggily; become

bedraggled while in an equestrian content it described a horse moving with a

gait between a trot and a gallop (a canter).

For those still brave enough to dare, the present participle is trolloping

and the past participle trolloped while the noun plural (the breed often

operating in pars or a pack) is trollops.

Floozie

(the alternative spellings floozy, floosy & floosie still seen although floogy is obsolete) was originally a corruption

of flossy, fancy or frilly in the sense of “showy” and dates only from the turn

of the twentieth century. Although it

was sometimes used to describe a prostitute or at least someone promiscuous, it

was more often applied in the sense of an often gaudily or provocatively dressed

temptress although the net seems to have been cast wide, disapproving mothers often

describing as floozies friendly girls who just like to get to know young men.

Strum

and trollop weren’t the only words in this vein to have more than one

meaning. Harlot was from the Middle

English harlot, from Old French harlot, herlot & arlot (vagabond;

tramp), of uncertain origin but probably from a Germanic source, either a

derivation of harjaz (army; camp;

warrior; military leader) or from a diminutive of karilaz (man; fellow). It

was an exclusively derogatory and offensive form which meant (1) a female

prostitute, (2) a woman thought promiscuous woman and (3) a churl; a common person

(male or female), of low birth, especially who leading an unsavoury life or given

to low conduct.

Lord Beaverbrook (1950), oil on canvas by Graham Sutherland (1903–1980). It’s been interesting to note that as the years pass, Rupert Murdoch (b 1931) more and more resembles Beaverbrook.

Increasing

sensitivity to the way language can reinforce the misogyny which has probably

always characterized politics (in the West it’s now more of an undercurrent) means

words like harlot which once added a colorful robustness to political rhetoric are

now rarely heard. One of the celebrated

instances of use came in 1937 when Stanley Baldwin’s (1867–1947; leader of the

UK’s Tory Party and thrice prime-minister 1923 to 1937) hold on the party

leadership was threatened by Lord Rothermere (1868-1940) and Lord Beaverbrook

(1879-1964), two very rich newspaper proprietors (the sort of folk Mr Trump would

now call the “fake news media”). Whether he would prevail depended on his

preferred candidate winning a by-election and three days prior to the poll, on 17

March 1931, Baldwin attacked the press barons in a public address:

“The newspapers attacking me are not newspapers

in the ordinary sense; they are engines of propaganda for the constantly

changing policies, desires, personal vices, personal likes and dislikes of the

two men. What are their methods? Their methods are direct falsehoods,

misrepresentation, half-truths, the alteration of the speaker's meaning by

publishing a sentence apart from the context and what the proprietorship of

these papers is aiming at is power, and power without responsibility, the

prerogative of the harlot throughout the ages.”

The

harlot line overnight became a famous quotation and in one of the ironies of

history, Baldwin borrowed it from his cousin, the writer Rudyard Kipling

(1865-1936) who had used it during a discussion with the same Lord Beaverbrook. Like a good many (including his biographer AJP

Taylor (1906-1990) who should have known better), Kipling had been attracted by

Beaverbrook’s energy and charm but found the inconsistency of his newspapers

puzzling, finally asking him to explain his strategy. He replied “What I want is power. Kiss ‘em one day and kick ‘em the next’ and so on”. “I see”

replied Kipling, “Power without

responsibility, the prerogative of the harlot throughout the ages.” Baldwin received his cousin’s permission to

recycle the phrase in public.

While

not exactly respectable but having not descended to prostitution, there was

also the hussy (the alternative spellings hussif,

hussiv & even hussy all

obsolete). Hussy was a Middle English

word from the earlier hussive & hussif, an unexceptional evolution of the

Middle English houswyf (housewife)

and the Modern English housewife is a restoration of the compound (which for

centuries had been extinct) after its component parts had become unrecognisable through phonetic change. The idea of hussy as a housewife or

housekeeper is long obsolete (taking with it the related (and parallel) sense

of “a case or bag for needles, thread etc” which as late as the eighteenth

century was mention in judgements in English common law courts when discussing

as woman’s paraphernalia). It’s enduring

use is to describe women of loose virtue but it can be used either in a derogatory

or affectionate sense (something like a minx), the former seemingly often modified

with the adjective “shameless”, probably to the point of becoming clichéd.

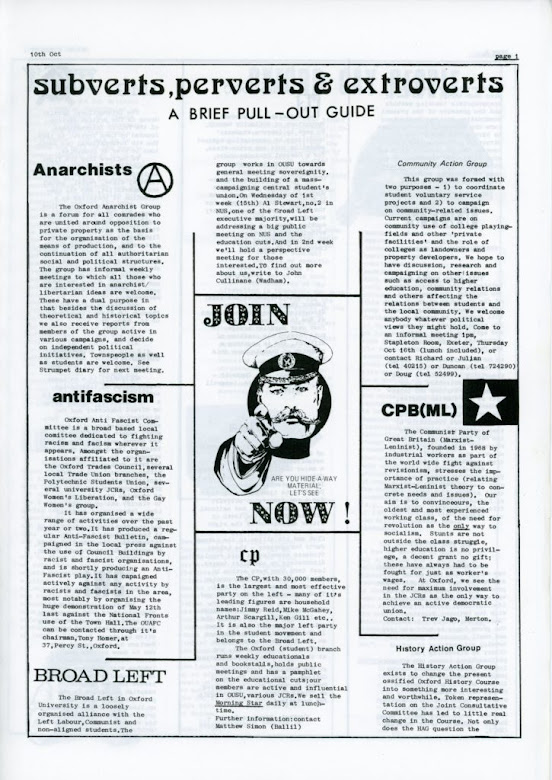

“An IMG Comrade, Subverts, Perverts & Extroverts: A Brief Pull-Out Guide”, The Oxford Strumpet, 10 October 1975.

Reflecting the left’s shift in emphasis as the process of decolonization unfolded and various civil rights movements gained critical mass in sections of white society, anti-racist activism became a core issue for collectives such as the International Marxist Group. Self-described as “the British section of the Fourth International”, by the 1970s their political position was explicitly anti-colonial, anti-racist, and trans-national, expressed as: “We believe that the fight for socialism necessitates the abolition of all forms of oppression, class, racial, sexual and imperialist, and the construction of socialism on a world wide scale”. Not everything published in The Oxford Strumpet was in the (evolved) tradition of the Fourth International and it promoted a wide range of leftist and progressive student movements.

Lindsay Lohan in rather fetching, strumpet-red underwear.

The Oxford Strumpet was an alternative left newspaper published within the University of Oxford and sold locally. It had a focus on university politics and events but also included comment and analysis of national and international politics. With a typically undergraduate sense of humor, the name was chosen to (1) convey something of the anti-establishment editorial attitude and (2) allude to the color red, long identified with the left (the red-blue thing in recent US politics is a historical accident which dates from a choice by the directors of the coverage of election results on color television broadcasts). However, by 1975, feminist criticism of the use of "Strumpet" persuaded the editors to change the name to "Red Herring" and edition 130 was the final Strumpet. Red Herring did not survive the decline of the left after the demise of the Soviet Union and was unrelated to the Red Herring media company which during the turn-of-the-century dot-com era published both print and digital editions of a tech-oriented magazine. Red Herring still operates as a player in the technology news business and also hosts events, its business model the creation of “top 100” lists which can be awarded to individuals or representatives of companies who have paid the fee to attend. Before it changed ownership and switched its focus exclusively to the tech ecosystem, Red Herring magazine had circulated within the venture capital community and the name had been a playful in-joke, a “red herring” being bankers slang for a prospectus issued with IPO (initial public offering) stock offers.