Monocoque (pronounced mon-uh-kohk or mon-oh-kok (non-U))

(1) A type of boat, aircraft, or rocket construction in which the shell carries most of the stresses.

(2) A type of automotive construction in which the body is combined with the chassis as a single unit.

(3) A unit of this type.

1911: From the French monocoque (best translated as “single shell” or “single hull” depending on application), the construct being mono- + coque. Mono was from the Ancient Greek μόνος (monos) (alone, only, sole, single), from the primitive Indo-European root men (small, isolated). Coque was from the Old French coque (shell) & concha (conch, shell), from the Latin coccum (berry) and concha (conch, shell) from the Ancient Greek κόκκος (kókkos) (grain, seed, berry). In the early twentieth century, it was the French who were most dominant in the development of aviation. Words like “monocoque”, “aileron”, “fuselage” and “empennage” are of French origin and endure in English because it’s a vacuum-cleaner of a language which sucks in anything from anywhere which is handy and manageable. Monocoque is a noun; the noun plural is monocoques.

Noted monocoques

Deperdussin Monocoque, 1912.A monocoque (sometime referred to as structural skin) is a form of structural engineering where loads and stresses are distributed through an object's external skin rather than a frame; concept is most analogous with an egg shell. Early airplanes were built using wood or steel tubes covered with starched fabric, the fabric rendering contributing only a small part to rigidity. A monocoque construction integrates skin and frame into a single load-bearing shell, reducing weight and adding strength. Although examples flew as early as 1911, airframes built as aluminium-alloy monocoques would not become common until the mid 1930s. In a pure design where only function matters, almost anything can be made a stressed component, even engine blocks and windscreens.

Lotus 25, 1962.

In automotive design, the word monocoque is often misused, treated as a descriptor for anything built without a separate chassis. In fact, most road vehicles, apart from a handful of expensive exotics, are built either with a separate chassis (trucks and some SUVs) or are of unibody/unitary construction where box sections, bulkheads and tubes to provide most of the structural integrity, the outer-skin adding little or no strength or stiffness. Monocoque construction was first seen in Formula one in 1962, rendered always in aluminium alloys until 1981 when McLaren adopted carbon-fibre. A year later, the McLaren F1 followed the same principles, becoming the first road car built as a carbon-fibre monocoque.

BRM P83 (H16), 1966.

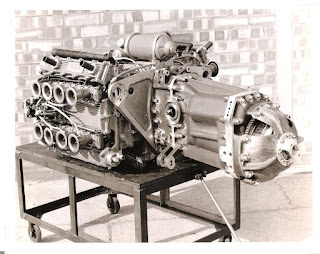

In 1966, there was nothing revolutionary about the BRM P83’s monocoque chassis. Four years earlier, in the second season of the voiturette era, that revolution had been triggered by the Lotus 25, built with the first fully stressed monocoque chassis, an epoch still unfolding as materials engineering evolves; the carbon-fibre monocoques seen first in the 1981 McLaren MP4/1 becoming soon ubiquitous. The P83 used a monocoque made from riveted Duralumin (the word a portmanteau of durable and aluminium), an orthodox construction for the time. Additionally, although it had been done before and would soon become an orthodoxy, what was unusual was that the engine was a stressed part of the monocoque.

BRM Type 15 (V16), 1949.

The innovation was born of necessity. Not discouraged by the glorious failure of the extraordinary V16 BRM had built (with much much fanfare and precious little success) shortly after the war, the decision was taken again to join together two V8s in one sixteen cylinder unit. Whereas in 1949, the V8s had been coupled at the centre to create a V16, for 1966, the engines were re-cast as 180o flat 8s with one mounted atop another in an H configuration, a two-crankshaft arrangement not seen since the big Napier-Sabre H24 aero-engines used in the last days of the war. The design yielded the advantage that it was short, affording designers some flexibility in lineal placement, but little else. It was heavy and tall, exacerbating further the high centre of gravity already created by the need to raise the engine location so the lower exhaust systems would clear the ground. Just as significantly, it was wide, too wide to fit into a monocoque socket and thus was taken the decision to make the engine an integral, load-bearing element of the chassis. There was no other choice.

BRM H16 engine and gearbox, 1966.

The 300 SLR (Sport Leicht Rennsport (Sport Light Racing)) which crashed was an open version and the model name was a little opportunistic because it was essentially the W196R Formula One car with a 3.0 litre straight-8 (the F1 rules demanded a 2.5) so the SLR, built to contest the World Sports Car Championship, was technically the W196S; it became the 300 SLR to cross-associate it and the 300 SL gullwing (W198, 1954-1957). Nine were built, two of which were converted to SLR gullwings and, although never raced, they came to be dubbed the “Uhlenhaut coupés” because they were co-opted by racing team manager Rudolf Uhlenhaut (1906–1989) as high-speed personal transport, tales of his rapid trips between German cities soon the stuff of legend and even if a few myths developed, the cars could exceed 290 km/h (180 mph) so some at least were probably true. That what was essentially a Grand Prix race car with a body and headlights could be registered for road use is as illustrative as safety standards at Le Mans of how different was the world of the 1950s. In 2022, one of the Uhlenhaut coupés was sold at auction to an unknown buyer (presumed to be Middle Eastern) for US$142 million, becoming by some margin the world’s most expensive used car.

As a footnote (one to be noted only by the subset of word nerds who delight in the details of nomenclature), for decades, it was said by many, even normally reliable sources, that SL stood for sports Sports Leicht (sports light) and the history of the Mercedes-Benz alphabet soup was such that it could have gone either way (the SSKL (1929) was the Super Sports Kurz (short) Leicht (light) and from the 1950s on, for the SL, even the factory variously used Sports Leicht and Super Leicht. It was only in 2017 it published a 1952 paper (unearthed from the corporate archive) confirming the correct abbreviation is Super Leicht. Sports Leicht Rennsport (Sport Light Racing) seems to be used for the the SLRs because they were built as pure race cars, the W198 and later SLs being road cars but there are references also to Super Leicht Rennsport. By implication, that would suggest the original 300SL (the 1951 W194) should have been a Sport Leicht because it was built only for competition but given the relevant document dates from 1952, it must have been a reference to the W194 which is thus also a Sport Leicht. Further to muddy the waters, in 1957 the factory prepared two lightweight cars based on the new 300 SL Roadster (1957-1963) for use in US road racing and these were (at the time) designated 300 SLS (Sports Leicht Sport), the occasional reference (in translation) as "Sports Light Special" not supported by any evidence. The best quirk of the SLS tale however is the machine which inspired the model was a one-off race-car built by Californian coachbuilder ("body-man" in the vernacular of the West Coast hot rod community) Chuck Porter (1915-1982). Porter's SLS was built on the space-fame of a wrecked 300 SL gullwing (purchased for a reputed US$500) and followed the lines of the 300 SLR roadsters as closely as the W198 frame (taller than that of the W196S) allowed. Although it was never an "official" designation, Porter referred to his creation as SL-S, the appended "S" standing for "scrap".

The SLR and its antecedents.

A Uhlenhaut coupé and a 300 SLR of course appeared for the photo sessions when in 2003 the factory staged the official release of the SLR McLaren and to may explicit the link with the past, the phrase “gullwing doors” appeared in the press kit documents no less than seven times. Presumably, journalists got the message but they weren’t fooled and the doors have always, correctly, been called “butterflies”. Unlike the machines of the 1950s which were built with an aluminium skin atop a space-frame, the twenty-first century SLRs were a monocoque (engineers say the sometimes heard “monocoque shell” is tautological) of reinforced carbon fibre. Although the dynamic qualities were acknowledged and it was, by all but the measure of hyper-cars, very fast indeed, the reception it has enjoyed has always been strangely muted, testers seeming to find the thing rather “soulless”. That seemed to imply a lack of “character” which really seems to suggest an absence of obvious flaws, the quirks and idiosyncrasies which can at once enrage and endear.

The nature of monocoque.

The monocoque construction offered one obvious advantage in that the inherent stiffness was such that the creation of the roadster version required few modifications, the integrity of the structure such that not even the absence of a roof compromised things. Notably, the butterfly doors were able to be hinged along the windscreen (A) pillars, such was the rigidity offered by carbon fibre, a material for which the monocoque may have been invented. McLaren would later use a variation of this idea when it released the McLaren MP4-12C (2011-2014), omitting the top hinge which allowed the use of frameless windows even on the roadster (spider) version.

The SLR Speedster (right) was named the Stirling Moss edition and was a homage to the 300 SLR (left) which in the hands of Sir Stirling Moss (1929–2020) and navigator Denis Jenkinson (1920–1996), won the 1955 Mille Miglia (an event run on public roads in Italy over a distance of 1597 km (992 miles)) at an average speed of 157.65 km/h (97.96 mph).

However, the minimalist (though very expensive) Speedster had never been envisaged when the monocoque was designed and to ensure structural integrity, changes had to be made to strengthen what would have become points of potential failure, the removal of the windscreen fame and assembly having previously contributed much to rigidity. Door sills were raised (recalling the space frame which in 1951 had necessitated the adoption of the original gullwing doors on the first 300 SL (W194)) and cross-members were added across the cockpit, integrated with a pair of rollover protection bars. Designed for speed, the Speedster eschewed niceties such as air-conditioning, an audio system, side windows and sound insulation; this was not a car for Paris Hilton. All told, despite the additional bracing, the Speedster weighed 140 kg (310 lb) less than the coupé while the supercharged 5.5 litre V8 was carried over from the earlier 722 edition but the reduction in frontal area added a little to top speed, now claimed to be 350 km/h (217 mph) although the factory did caution that above 160 km/h (100 mph), the dainty wind deflectors would no longer contain the wind and a crash helmet would be required so even if the lack of air-conditioning might have been overlooked, that alone would have been enough for Paris Hilton to cross the Speedster off her list; she wouldn't want "helmet hair". Only 75 were built, none apparently ever driven, all spending their time on display or the auction block, exchanged between collectors.