Catfish (pronounced kat-fish)

(1) In ichthyology, any of the numerous mainly freshwater teleost fishes

of the order or suborder Nematognathi (or Siluroidei), characterized by barbels

around the mouth and the absence of scales, especially the silurids of Europe

and Asia and the horned pouts of North America.

(2) A wolffish of the genus Anarhichas.

(3) In casual use, any of various other fishes having a

fancied resemblance to a catfish.

(4) In slang, a person who assumes a false identity or

personality on the internet, especially on social media, usually with an intent

to deceive, manipulate, or swindle.

(5) To deceive, swindle, etc by assuming a false

identity or personality online.

(6) In casual use, any piece of machinery having a fancied resemblance to a catfish (applied often to cars with "gaping grills" ).

1605–1615: The construct was cat + fish. Dating from circa 700, cat was from the Middle

English cat or catte and the Old English catt

(masculine) & catte

(feminine). It was cognate with the Old

Frisian and Middle Dutch katte, the Old

High German kazza, Old Norse köttr, Irish cat, Welsh cath (thought derived from the Slavic kotŭ), the Russian kot and the Lithuanian katė̃; the Old French chat enduring. The curious Late

Latin cattus or catta was first noted in the fourth century, presumably associated

with the arrival of domestic cats but of uncertain origin. The Old English catt appears derived from the earlier (circa 400-440) West Germanic

form which came from the Proto-Germanic kattuz

which evolved into the Germanic forms, the Old Frisian katte, the Old Norse köttr,

the Dutch kat, the Old High German kazza and the German Katze, the ultimate source being the Late

Latin cattus.

The noun fish was from the pre-900 Middle English fish, fisch & fyssh, from the Old English fisc

(fish), from the Proto-West Germanic fisk,

from the Proto-Germanic fiskaz (fish). It was cognate with the West Frisian fisk, the Dutch vis, the Old Norse fiskr,

the Danish fisk, the Norwegian fisk, the Gothic fisks, the Swedish fisk and

the German Fisch, the ultimate source

probably the primitive Indo-European peysḱ (fish) & pisk (a fish) although there are

etymologist who speculate, on phonetic grounds, that it may be a north-western

Europe substratum word. It was akin to

the Latin piscis, the Irish verb iasc, the Middle English fishen and the Old English fiscian, cognate with the Dutch visschen, the German fischen, the Old Norse fiska and the Gothic fiskôn.

The verb fish was from the Old English fiscian (to fish, to catch or try to catch fish). It was cognate with the Old Norse fiska, the Old High German fiscon, the German fischen and the Gothic fiskon.

The catfish seems to have gained its name early in the

seventeenth century following the practice adopted for the Atlantic wolf-fish, noted

for its ferocity, the catfish picking up its moniker apparently because of the "whiskers"

although the "purring" sound it sometimes makes upon being taken from the water

has (less convincingly) been suggested as the origin; most zoologists and etymologists prefer the

whiskers story while noting the correct name for the appendages is barbels. Catfish & catfishing are nouns & verbs, catfisher is a noun, catfished is a verb and catfishlike & catfishesque (the latter listed by some as non-standard) are adjectives, the noun plural is catfish or catfishes.

Strictly speaking, the choice of the plural form (catfish or catfishes) should folow the usual convention in matters ichthyological. The plural of "fish" is an illustration of the inconsistency of English. As the plural form, “fish” & “fishes” are often (and harmlessly) used interchangeably but in zoology, there is a distinction, fish (1) the noun singular & (2) the plural when referring to multiple individuals from a single species while fishes is the noun plural used to describe different species or species groups. The differentiation is thus similar to that between people and peoples yet different from the use adopted when speaking of sheep and, although opinion is divided on which is misleading (the depictions vary), the zodiac sign Pisces is referred to variously as both fish & fishes. So, it is correct to speak of multiple catfish if all are of the same species but to use "catfishes" if there's a mix. In cooking (the frequent collective being "catfish stew"), or any reference to use as food (or bait), the plural is without exception "catfish".

"Catfish" is now understood in a way which a generation earlier would to many have been baffling although the modern use does pick up an earlier tradition.

The modern term catfishing describes a type on nefarious

on-line activity in which a person uses information and images, typically taken

from others, to construct a new identity for themselves. In the most extreme examples, a catfisher can

steal and assume another individual’s entire identity, enabling the possibility

of using the fake persona to engage in fraud or other illegal

activities. Catfishing attacks may be

targeted or opportunistic and have long been common on dating sites. One niche activity is where only a few (or

legally insignificant) elements are involved

(usually in an attempt to tempt younger subjects on dating sites) and there is

no attempt to engage in illegal activity; this has been called "kitten fishing". There is nothing new in the concept of catfishing, cases

documented in the literature for centuries, the ubiquity of the internet just

making such scams both easier to execute and detect so in its latest use, "catfish" is one of those terms which achieved critical linguistic mass because of the adoption of newly available technology, joining those words which have for centuries been either coined or re-purposed in a kind of technological determinism. The term in this context is derived from the 2010

American documentary Catfish, which

concerned a 26 year old man who, thinking he was building an on-line

relationship with a 19 year old woman, discovered his digital interlocutor was

actually a married women of 40. The documentary

(and thus the on-line behavior) gained the name from a mention the woman's

husband made when comparing his wife’s conduct to the myth that it was once the

practice to include one or more catfish in the tank when shipping live cod, the

rationale said to be the cod would remain active in the presence of catfish

whereas if shipped alone, they would become pale and lethargic, reducing the quality

of the flesh. The source of the myth was

the 1913 psychological novel Catfish

by Charles Marriott (1869-1957), the fanciful story repeated that same year by Henry

Wooded Nevinson (1856-1941) in his political treatise, Essays in Rebellion. The emergence on the internet of "catfishing" begat "sadfishing", the technique (most associated with the emo) of posting about one's unhappiness or emotional state ("I am just devastated" a favorite phrase of the habitually heartbroken emo) on social media platforms, the object being to attract attention and sympathy; it's regarded in many cases as the seeking of "validation".

Etymologically unrelated (although not wholly dissimilar

in practice) was the earlier internet slang "phishing" which described a kind of social

engineering in which an attacker sends a deceptive message

designed to trick a person into revealing sensitive information or induce them

in some way to install malicious software such as key-stroke grabbers or ransomware.

Phishing is a leetspeak (the use of alphanumeric substitutions in text-strings) variant of "fishing" which compares the digital activity to actual angling, the idea being the

casting of lines with lures in the hope there will be bites at the deceptive bait. The first known reference to phishing dates

from 1995 but there was apparently an earlier mention in the magazine 2600: The Hacker Quarterly, the word

coined following the earlier phreaking.

Phishing was for years the numerically most common form of attack by

cybercriminals.

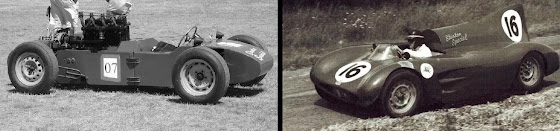

The "Catfish Cars"

Catfish and some cars they inspired.

First seen on a few eccentric examples during the inter-war years, the

distinctive “catfish look” emerged on volume

production automobiles during the 1950s.

Even then the look seemed a stylistic curiosity but it was an age of

extravagance and among the macropterous creations of the era, the catfish cars represented

just one of many directions the industry could have followed. Nor was the catfish look wholly without

engineering merit, the low hood (bonnet) line improving aerodynamic efficiency,

the wide, gaping aperture of the grill permitting adequate air-flow for engine

cooling with headlamps able still to satisfy regulatory height requirements. Classic examples of catfish styling includes

the original Citroen DS (top left), the Packard Hawk (top centre) and the Daimler SP250 (top right).

Daimler SP250 (1959-1964).

The Daimler SP250 was first shown to the public at the 1959

New York Motor Show and there the problems began. Aware the little sports car was quite a

departure from the luxurious but rather staid range Daimler had for years

offered, the company had chosen the pleasingly alliterative “Dart” as its name,

hoping it would convey the sense of something agile and fast. Unfortunately, Chrysler’s lawyers were faster

still, objecting that they had already registered Dart as the name for a

full-sized Dodge so Daimler needed a new name and quickly; the big Dodge would

never be confused with the little Daimler but the lawyers insisted. Uniquely,

the car displayed at the New York show genuinely was (and remains) a “Daimler

Dart” because that’s the name under which it was registered in the UK prior to

shipping and, after spending some forty years in Canada, it made a return

trans-Atlantic voyage, becoming an exhibit in the JDHT (Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust) Museum in Gaydon, Warwickshire.

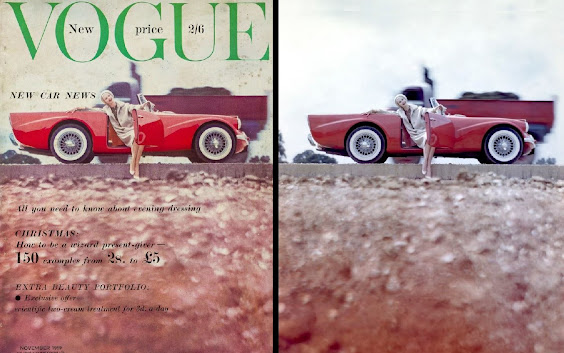

Using one of his trademark outdoor settings, Norman Parkinson (1913-1990) photographed model Suzanne Kinnear (b 1935) adorning a Daimler SP250, wearing a Kashmoor coat and Otto Lucas beret with jewels by Cartier. Note the differences in color saturation.

The image appeared on the cover (left) of Vogue's UK edition in November 1959, the original's (right) colors being "enhanced" in the Vogue pre-publication editing tradition (women thinner, cars shinier). The wide whitewall tyres were a thing at the time, even on sports cars and were a popular option on US market Jaguar E-Types (1961-1974 and there (unofficially) known also as XK-E or XKE) in the early 1960s. The car on the Vogue cover was XHP 438, built on prototype chassis 100002 at Compton Verney in 1959; it's the oldest surviving SP250, the other two prototypes (chassis 100000 & 100001 from 1958) dismantled when testing was completed. XHP 438 was the factory's press demonstrator and was used in road tests by Motor and Autocar magazines before being re-furbished (motoring journalists subjecting the press fleet to a brief but hard life) and sold.

Imagination apparently exhausted, Daimler’s

management reverted to the engineering project name and thus the car became the SP250 which was innocuous enough even for Chrysler's attorneys and it could have been worse. Dodge had

submitted their Dart proposal to Chrysler for approval and while the car found

favor, the name did not and the marketing department was told to conduct

research and come up with something the public would like. From this the marketing types gleaned that “Dodge

Zipp” would be popular and to be fair, dart and zip(p) do imply much the same

thing but ultimately the original was preferred and Darts remained in Dodge’s

lineup until 1976, for most of that time one of the corporation's best-selling

and most profitable lines. The name was

revived between 2012-2016 for an unsuccessful and unlamented compact sedan.

1962 Daimler SP250 (B-Spec).

Daimler’s SP250 didn’t enjoy the same longevity, the last

of the 2654 produced in 1964, sales never having approached the projected 3000

per year, most of which were expected to be absorbed by the lucrative US market. The catfish styling probably didn’t help, a

hint being the informal poll taken at the 1959 show when the thing was voted “the

ugliest car of the show” but lurking beneath the feathers of the ugly duckling was a virile swan. The heart of the SP250 was a jewel-like, 2.5

litre (155 cubic inch) hemi-headed V8 which combined the structure of Cadillac’s

V8 with advanced cylinder heads which owed much to those of the Triumph

Thunderbird motorcycle engine. Indeed, the

designer, Edward Turner (1901–1973), owned a Cadillac and was responsible for

the Triumph heads so the influences weren’t surprising and the little engine

had an interesting gestation. It was

Turner’s first car engine and so tied was he to the principles which had proved

so successful for his motorcycles that the original concept was air-cooled and

fed by eight carburetors. Reality however soon beckoned and what emerged was a compact, light (190 KG (419 lb)),

water-cooled V8 with the inevitable twin SU carburetors, the project yielding

also an only slightly bulkier (226 KG (498 lb)) 4.6 litre (278 cubic inch) version

which would be tragically under-utilized by a British motor industry which greatly could have benefited from a wider deployment of both instead of some engines

which proved pure folly. The Daimler V8s

are notable too for their intoxicating exhaust notes, perhaps not a critical

aspect of engineering but one which adds much to the pleasure of ownership.

Daimler SP250, winner of the 1962 Bathurst 6 Hour Classic, driven by brothers Leo Geoghegan (1936-2015) and Ian (Pete) Geoghegan (1939-2003).

Under-capitalized and lacking the funds needed to revitalize

their dated range, let alone develop new high-volume models, the SP250 was

created on a shoestring budget, the chassis blatantly reverse-engineered (ie copied) from the Triumph TRs with a body built in the then still novel GRP (Glass Reinforced Plastic which became better known as fibreglass), not by deliberate choice but because the tooling and related

production facilities could be fabricated for a fraction of the cost had steel

or aluminum been used. It also lessened

the development time and promised a simpler and cheaper upgrade path in the

future but also brought problems of its own.

New to the material, Daimler’s engineers were confronted with many of

the same problems which Chevrolet encountered during the early days of the

Corvette, issues which even with the vast resources of General Motors, proved

troublesome. Other than the fibreglass

body, the SP250 was technologically conventional, using a chassis little

different from that of the Triumph TR3, built in a 14 gauge box section with

central cruciform bracing. The chassis

was designed to be light and that was certainly achieved but at the cost of

structural rigidity, again an issue of the use of fibreglass, the engineers (in

pre-CAD times) under-estimating the stiffness which would be demanded in a

structure without metal panels further to distribute the loadings.

1962 Daimler SP250 in British Racing Green (BRG) with factory

hard-top and Minilite wheels.

The lack of sufficient torsional rigidity meant the SP250s

were beset with the same teething problem as the first Corvettes: the

fibreglass panels could become crazed or even crack and, most disconcertingly,

doors were prone to springing open during brisk cornering and the hood sometimes popped open as the body flexed at high speed. The SP250 was a genuinely fast car so these

were not minor issues. Still, there was

much to commend the SP250. Wind-up

windows and the availability of an automatic transmission sound hardly

ground-breaking but they were an innovation unknown on the MG, Triumph and

Austin-Healy roadsters of the time and the in UK the little V8 was unique. The suspension was conventional but

competent, an independent front end with upper and lower arms, coil springs,

and telescopic shock absorbers while the rear used semi-elliptic leaf springs

with lever arm shock absorbers. The unassisted

cam and peg system steering lacked the precision the Italians achieved even

without using a rack and pinion system but, aided by a larger than usual

steering wheel, it offered a reasonable compromise for the time although at low

speed it was far from effortless. More

commendable were the brakes. The

four-wheel disks had no power assistance but the SP250 was a light car and the

servo systems of the time, lacking feel and impeding the progressiveness

inherent in the design of the early disks, meant unassisted systems were

preferable for sports cars although, efficient and fade-free though they were,

an emergency stop from speed did demand high pedal effort. One curiosity in the configuration was the bumper bars. Considering the issue bumpers would become in the 1970s, that they were once optional is an indication of how different the regulatory environment was at the time. The A spec SP250s had no bumpers as standard equipment but were fitted at the front with what are sometimes mistakenly called nerf-bars but are actually “bumperettes” although the English seem to like “whiskers”. At the rear were over-riders attached to nerf-bars. The B spec models didn’t include these but, like the A spec, the full bumpers were an optional extra and this setup was continued for the C spec. The SP250s used by the British Metropolitan Police as high speed pursuit cars always had the optional bumpers because of the need to mount the warning bell and auxiliary spotlight.

1960 Daimler SP250 (automatic) in UK police pursuit specification. The automatic transmission was the robust Borg-Warner Model 8 and after the run of police cars was complete, the option was made available to the public.

So, developed to the extent possible with the resources

available, production began in 1959, shortly before the Birmingham Small Arms

Company (BSA) announced the sale of Daimler to Jaguar. Jaguar, attracted by Daimler’s extensive manufacturing

facilities and its skilled workforce regarded most of the Daimler range as

antiquated but allowed some production to continue although their engineers

decided the chassis of the SP250 needed significant modifications to improve

rigidity. The strengthening was

undertaken and the revised cars became known as the “B-Spec” models, introduced in between April 1961, original specification (1959-1961) retrospectively labeled as “A-Spec”. Although transformative, the changes were not extensive, a steel

box section hoop added to connect the windscreen pillars, two steel outrigger

sill beams along each side of the chassis, complimented with a couple of strategically

placed braces but the stiffer structure

solved the most of the problems.

Apart from the attention to the structure, product development was restricted to equipment, the B-Spec cars gaining (from the A-Spec option list) a reserve petrol tank with switch, windscreen washers and exhaust finishers; additionally, although technically still an option, many were factory-fitted with the chrome bumpers. The C-spec range included luxuries such as a cigar lighter, heater & demister and trickle charger socket and when production ended in 1964, the final count was something like A-Spec: 1900; B-Spec: 500 and C-Spec 254 (and there was overlap in the inclusion of specific features as the factory transitioned from one to another). More than sixty years on, the SP250 survival rate is high, assisted by the rust-proof body and robust mechanicals but because so many have over the years been upgraded to "B" & "C" Spec (or a mixture), truly original specimens are rare. Intricacies

in the option mix apply mostly to home-market cars because export vehicles

tended to be more fully-equipped. All

destined for North America were fitted with the full width front bumper and rear

over-riders (the full-width rear an option) as well as most of the fittings

which were extra-cost options in the UK including the cigar lighter (described in the US as a cigarette lighter), heater & demister and windscreen washers, the

latter in the early 1960s not a mandated requirement in the UK.

Daimler SP252 prototype (1964). The

reason the code-name was SP252 rather than SP251 is SP251 was the

factory designation for LHD (left-hand-drive) SP250s. Had the SP250 in 1959 debuted with this body, history might have been different.

Unfortunately, Jaguar was never enthusiastic about

Daimler except for the factory's manufacturing capacity and as a badge which could be used on up-market Jaguars sold at a

nice profit. However, whatever the

opinions of the catfish styling, the SP250 had proved itself in motorsport and, capable of a then impressive 122 mph (196 km/h), had been used as a high-speed pursuit vehicle by a number of police forces,

interestingly usually with an automatic transmission, the choice made in the

interest of reduced maintenance, a conclusion rental car companies would one day reach. For that reason, the potential

was clear and Jaguar explored a way to extend the appeal with a restyled

body. The result was the SP252, rendered

still in fibreglass but now more elegantly done, hints of the influence of the MGB (1962-1980) obvious while the rear owed some debt to Aston Martin’s DB4 (1958-1963). Aesthetically accomplished though it was, economic

reality prevailed. The factory was tooled-up to produce no more than 140 of the V8 engines each week, demand for which

was already exceeding supply since it had been offered in the Jaguar Mk2-based

Daimler 2.5 V8 (1962-1967 and badged as 250 1967-1969) saloon and Jaguar lacked the production capacity even to make enough E-types to meet demand. Given

that and the engineering resources required to devote to the new V12

engine and the XJ6 for which it was intended, another relatively

low-volume project couldn’t be justified, especially one which likely would cannibalize the E-Type's market.

Jaguar missed an opportunity by not making better use of the Daimler V8s. The smaller unit could have been enlarged to 2.8 litres to take advantage of the taxation rules in continental Europe and in the XJ would have been a more convincing powerplant than the 2.8 XK six which was always underpowered and prone to overheating. When fitted to a prototype Jaguar Mark X, the 4.6 litre V8 had proved outstanding and, easily able to be expanded beyond five litres, it would have been ideal for the lucrative US market and the thought of a 4.6 V8 E-Type (XKE) remains tantalizing. Unfortunately, Jaguar was besotted with the notion of V12s and it wasn't until the 1990s they admitted the sweet-spot in the market was a V8 between 4-5 litres, the very thing they'd acquired with the purchase of Daimler in 1960.

Produced between 1955-1975, the Citroën DS, although long

regarded as something quintessentially French, was actually designed mostly by an

Italian. In this it was similar to French fries (invented in Belgium) and Nicolas Sarközy (b 1955; President of France 2007-2012), who first appeared in the same year as the shapely DS and was from here and there. It was offered as the

DS and the lower priced, mechanically simpler ID, the names apparently an

deliberate play on words, DS in French pronounced déesse (goddess) and ID idée

(idea) but while the nickname "goddess" caught on, "idea" never did. The frontal aspect combined

with the efficiency of the rest of the body, delivered outstandingly good

aerodynamics but the catfish look was tempered a little because the low, gaping

grill associated with the motif was well-concealed, reputedly because the ancient

engine, a long-stroke, agricultural relic of the 1930s, produced so little

power there wasn’t enough surplus energy to induce overheating, the need for a

cooling flow of air correspondingly low.

That’s wholly apocryphal but later progress in design anyway softened

the catfish effect which was most obvious

on the series 1 cars (top row) which were made between 1955-1962. The Series 2 changes (1964-1967; centre row) were

effected further to improve aerodynamics and permitted also some increase to

the airflow ducted for interior ventilation; the changes in appearance were

said to be incidental to the process. The catfish look vanished entirely when the series 3 cars (bottom row) were introduced

in 1967.

Now with four headlamps mounted behind glass canopies,

the shape of which was integrated into the front fenders (top left), the

arrangement was noted for the novelty of the inner set of lens being controlled

by the steering (top right), the light thus being projected “around the corner”

in the direction of travel, swiveling by up to 80°. It was a simple, purely mechanical connection

and the system had in 1929 appeared on the FWD (front-wheel-drive) Cord L-29 (1929-1932) to to direct the auxiliary driving or fog-lights and

the central (Cyclops) unit on the abortive Tucker Torpedo (1948) had been

configured the same way but the DS was the first car in series-production to use adaptive headlights. Both the covers and the

turning mechanism fell foul of US regulations (lower left) so there the lens

were fixed and exposed. Another

variation was in Scandinavia where miniature wipers were sometimes fitted to conform with local law. In the collector market, the small feature can add a remarkable premium to the value of a car, rare factory options highly sought.

1964 Citroën DW19 Décapotable Usine. For statistical purposes the DWs are included in the DS production count.

The DS and ID are well documented in the model's history but there was also the more obscure DW, built at Citroën's UK manufacturing plant in the Berkshire town Slough which sits in the Thames Valley, some 20 miles west of London. The facility was opened in February 1926 as part of the Slough Trading Estate (opened just after World War I (1914-1918)) which was an early example of an industrial park, the place having the advantage of having the required infrastructure needed because constructed by the government for wartime production and maintenance activities. Citroën was one of the first companies to establish an operation on the site, overseas assembly prompted by the UK government's imposition of tariffs (33.3% on imported vehicles, excluding commercial vehicles) and the move had the added advantage of the right-hand-drive (RHD) cars being able to be exported throughout the British Empire under the “Commonwealth Preference”, arrangements, a low-tariff scheme, elements of which would endure as a final relic of the chimera of imperial free trade until 1973 when the UK joined the EEC (European Economic Community). Unlike similar operations, which in decades to come would appear world-wide, the Slough Citroëns were not assembled from CKD (completely knocked down) kits which needed only local labor to bolt them together but used a mix of imported parts and locally produced components. The import tariff was avoided if the “local content” (labor and domestically produced (although those sourced from elsewhere in the empire could qualify) parts) reached a certain threshold (measured by the total P&L (parts & labor) value in local currency); it was an approach many governments would follow and it remains popular today as a means of encouraging (and protecting) local industries and creating employment. People able to find jobs in places like Slough would have been pleased but for those whose background meant they were less concerned with something as tiresome as paid-employment, the noise and dirt of factories seemed just a scar upon the “green and pleasant land” of William Blake (1757–1827). In his poem Slough (1937), Sir John Betjeman (1906–1984; Poet Laureate 1972-1984), perhaps recalling Stanley Baldwin's (1867–1947; UK prime-minister 1923-1924, 1924-1929 & 1935-1937) “The bomber will always get through” speech (1932) welcomed the thought, writing: “Come friendly bombs and fall on Slough! It isn’t fit for humans now” Within half a decade, the Luftwaffe would grant his wish.

During World War II (1939-1945), the Slough plant was requisitioned for military use and some 23,000 CMP (Canadian Military Pattern) trucks were built, civilian production resuming in 1946. After 1955, Slough built both the ID and DS, both with the traditional leather trim, the former with timber veneer dashboard, a touch which some critics claimed was jarring among the otherwise modernist ambiance but the appeal was real because some French distributors imported the Slough dashboard parts for owners who liked the look. The UK-built cars also used 12 volt Lucas electrics until 1963 and it was in that year the unique DW model was slotted in between the ID and DS. Available only with a manual transmission and a simplified version of the timber veneer, the DW was configured with the ID's foot-operated clutch but used the more powerful DS engine, power steering and power brakes. When exported, the DW was called DS19M and the "DW" label was applied simply because it was Citroën's internal code to distinguish (RHD) models built in the UK from the standard left-hand-drive (LHD) models produced in France. Citroën assembly in Slough ended in February 1965 and although the factory initially retained the plant as a marketing, service & distribution centre, in 1974 these operations were moved to other premises and the buildings were taken over by Mars Confectionery. Today, no trace remains of the Citroën works in Slough.

1958 Packard Hawk,

Fittingly perhaps, the gaping-mouth of the catfish style

was applied to what proved one of the last gasps for Packard, a storied marque with

roots in the nineteenth century which in the inter-war years had been one of

the most prestigious in the US and it had been the sound of the V12 Packards

which inspired Enzo Ferrari (1989-1988) to declare Una Ferrari è una macchina a dodici cilindri (a Ferrari is a twelve cylinder car). The appeal was real because it was a 1936 Packard Standard Eight Phaeton which comrade Stalin (1878-1953; Soviet leader 1924-1953) used as his parade car and the ZiS-115 limousine (1948-1949 and based on the ZiS 110 (1946-1958), all better known in the West as ZILs) he used in his final years was a reversed-engineered (ie copy) version of the 1942 Packard. Reverse-engineering was a notable feature of Soviet industry and much of its post-war re-building of the armed forces involved the process, exemplified by the Tupolev Tu-4 heavy bomber (1947) which was a remarkably close copy of the US Boeing B-29 (1942). Other countries also adopted the practice which in some places continues to this day for mot civilian and military output. After spending World War II engaged in military production, notably a version of the Merlin V12 aero-engine built under license from Rolls-Royce, Packard emerged in 1945 in

sound financial state but found the new world challenging, eventually in 1953 merging

with fellow struggling independent, Studebaker.

The mashup of period styling motifs (fins, dagmars, wrap-around glass, scallops & a scoop) on the 1958 Packard was not untypical in the era and the catfish treatment at the front was about the most restrained part of the package.

1957 Studebaker Golden Hawk. Whatever the criticism of the catfish-like Packard, the frontal treatment of the car on which it was based was perhaps even more ungainly.

The origins of Packard’s swansong, the Hawk, lay in a 1957

Studebaker Golden Hawk 400 which was customized in-house for executive

use. The front end and hood were rendered in fiberglass, eliminating the familiar upright grille and small

side inlets which were replaced with the low, wide air intake so characteristic

of the catfish look. Covering all bases, for those unconvinced by the catfish look, a pair of modest (by Cadillac standards) dagmars were added. Because the engine

was supercharged, like the Studebaker, the hood included a bulge but, by virtue of the lower lines, it rose higher on the Packard. Lacking the funds to create anything better,

the Hawk was approved for series-production as a 1958 model but was from

the start doomed. It was expensive and its

debut coincided with the recession of that year when all auto-makers suffered

downturns but, with the rumors swirling of Studebaker-Packard's impending demise,

Packard suffered more than most and only 588 Hawks were built.

1958 Packard with stuff tacked-on, front & rear.

Packard’s rather plaintive swansong was another set of cobbled-together

Packardbakers, available as a two-door hardtop and a four-door sedan or wagon. In 1958, fins were a thing at the rear but

what really exited the stylists was that quad headlamps were now permitted in

all 48 states. Unfortunately, unlike the majors, the financially straitened corporation lacked the capital to re-tool body dies to accommodate

the change so, hurriedly, fibreglass pods were molded which when fitted, looked

as tacked-on as they really were. Also

tacked on were the new fins which sat atop the old although these were at

least genuine steel rather than fibreglass. Sales of the 1958 proved as forlorn as the expectations of most industry observers with barely 2,000 sedans, hardtops & wagons built by the time production ended in July and in 1962, quietly it was confirmed Studebaker-Packard Corporation had deleted "Packard" from its

name, one of the less necessary press-releases in the industry's history. It was a barely noted formal end to a once illustrious marque which not ten years earlier had been the favorite of comrade

Stalin and the restructure was to little avail, the final Studebaker being produced in in Canada in 1966, two years after the last US factories had closed.

1958 Chrysler Royal (AP2) and 1960 Chrysler Royal (AP3) (Australian)

The fins were definitely always standard equipment on all 1958 Packards, unlike the 1958 Australian Chrysler Royal (AP2) which featured

similar appendages grafted to pre-existing fins, Chrysler listing them as an optional extra called "saddle fins". However, no Royal apparently was sold without saddle fins attached so either (1) they were very popular option or (2) Chrysler

changed their mind after the promotional material was printed and decided to

invent "mandatory options", a marketing trick Detroit would soon widely (and profitably) adopt. In 1960, the Australians also solved the

problem of needing to add quad headlamps without either a re-tool or plastic

pods, changing instead the grill and mounting the lights in a vertical stack,

an expedient Mercedes-Benz had recently used to ensure their new W111 (Heckflosse) sedans (1959-1968) satisfied

US legislation.