Flute (pronounced floot)

(1)

(2) An

organ stop with wide flue pipes, having a flutelike tone.

(3) In architecture or engineering (particularly the manufacture of firearms), a semi-cylindrical vertical channel, groove or furrow, as on the shaft of a column, in a pillar, in plaited cloth, or in a rifle barrel to cut down the weight.

(4) Any

groove or furrow, as in a ruffle of cloth or on a piecrust.

(5) One

of the helical grooves of a twist drill.

(6) A

slender, footed wineglass with a tall, conical bowl.

(7) A

similar stemmed glass, used especially for champagne and often styled as "champagne flute".

(8) In

steel fabrication, to kink or break in bending.

(9) In

various fields of design, to form longitudinal flutes or furrows.

(10) A long bread roll of French origin; a baguette.

(11) A shuttle in weaving, tapestry etc.

(12) To play on a flute; to make or utter a flutelike sound.

(13) To form flutes or channels in (as in a column, a ruffle etc); to cut a semi-cylindrical vertical groove in (as in a pillar etc).

1350-1400; From the Middle English floute, floute & flote, from the Middle French flaüte, flahute & fleüte, from the twelfth century Old French flaute (musical), from the Old Provençal flaüt (thought an alteration of flaujol or flauja) of uncertain origin but may be either (1) a blend of the Provencal flaut or flaujol (flageolet) + laut (lute) or (2) from the Classical Latin flātus (blowing), from flāre (to blow) although there is support among etymologists for the notion of it being a doublet of flauta & fluyt. In other languages, the variations include the Irish fliúit and the Welsh ffliwt. The form in Vulgar Latin has been cited as flabeolum but evidence is scant and all forms are thought imitative of the Classical Latin flāre and other Germanic words (eg flöte) are borrowings from French.

Portrait of Archduchess Maria Antonia of Austria (later Queen Marie Antoinette of France (1774-1792)), circa 1768, oil on canvas by Martin van Meytens (1695–1770).

Fluted & fluting both date from the 1610 while the verb (in the sense of "to play upon a flute" emerged in the late fourteenth century and the use to describe grooves in engineering dates from 1570s and the tall, slender wine glass, almost a century later although the term "champagne flute" didn't enter popular use until the 1950s. The champagne flute is preferred by many to the coupé (or saucer) even though it lacks the (since unfortunately debunked) legend that the shape of the latter was modelled on Marie Antoinette’s (1754-1793) left breast. Elegant though it is, the advantages of the flute are entirely functional, the design providing for less spillage than a coupé, something which comes to be more valued as lunch progresses and the slender, tapered shape is claimed better to preserved the integrity of the bubbles, the smaller surface area and thus reduced oxygen-to-wine ratio maintaining the aroma and taste.

Grand Cru's guide to the shape of champagne glasses.

Fluted grill on 1972 Series 1, 4.2 Litre Daimler Sovereign.

In British use, one who plays the flute is a flautist (pronounced flaw-tist (U) or flou-tist (non-U)), from the Italian flautista, the construct being flauto (flute) + -ista. The -ist suffix was from the Middle English -ist & -iste, from the Old French -iste and the Latin -ista, from the Ancient Greek -ιστής (-istḗs), from -ίζω (-ízō) (the -ize & -ise verbal suffix) and -τής (-tḗs) (the agent-noun suffix). It was added to nouns to denote various senses of association such as (1) a person who studies or practices a particular discipline, (2), one who uses a device of some kind, (3) one who engages in a particular type of activity, (4) one who suffers from a specific condition or syndrome, (5) one who subscribes to a particular theological doctrine or religious denomination, (6) one who has a certain ideology or set of beliefs, (7) one who owns or manages something and (8), a person who holds very particular views (often applied to those thought most offensive). The alternative forms are the unimaginative (though descriptive) flute-player and the clumsy pair fluter although the odd historian or music critic will use aulete, from the Ancient Greek αὐλητής (aulētḗs), from αὐλέω (auléō) (I play the flute), from αὐλός (aulós) (flute). The spelling flutist is preferred in the US and it's actually an old form, dating from circa 1600 and probably from the French flûtiste and it replaced the early thirteenth century Middle English flouter (from the Old French flauteor).

Daimler, the fluted grill and US trademark law

1972 Daimler Double-Six Vanden Plas.

Vanden Plas completed only 342 of the Series 1 (1972-1973) Daimler Double Sixes, the later Series 2 (1973-1979) & 3 (1979-1992) being more numerous. The flutes atop the grill date from the early twentieth-century and were originally a functional addition to the radiator to assist heat-dissipation but later became a mere styling embellishment. Although some sources claim there were 351 of the Series 1 Double-Six Vanden Plas, the factory insists the total was 342. British Leyland and its successor companies would continue to use the Vanden Plas name for some of the more highly-specified Daimlers but applied it also to Jaguars because in some markets the trademark to the Daimler name came to be held by Daimler-Benz AG (since 2022 Mercedes-Benz Group AG), a legacy from the earliest days of motor-car manufacturing and despite the English middle class always pronouncing the name van-dem-plarr, it's correctly pronounced van-dem-plass.

1976 Daimler Double-Six Vanden Plas two door.

The rarest Double-Six Vanden Plas was a genuine one-off, a two door built reputedly using one of the early prototypes, a regular production version contemplated but cancelled after the first was built. Jaguar would once have called such things fixed head coupés (FHC) but labelled the XJ derivatives as "two door saloons" and always referred to them thus, presumably as a point of differentiation with the XJ-S (later XJS) coupé produced at the same time. Despite the corporate linguistic nudge, everybody seems always to have called the two-door XJs "coupés". Why the project was cancelled isn't known but it was a time of industrial and financial turmoil for the company and distractions, however minor, may have been thought unwelcome. Although fully-finished, apart from the VDP-specific trim, it includes also some detail mechanical differences from the regular production two-door Double-Six although both use the distinctive fluted finish on both the grill and trunk (boot) lid trim; the car still exists. The two-door XJs (1975-1978) rank with the earliest versions (1961-1967) of the E-Type (XKE; 1961-1974) as the finest styling Jaguar ever achieved and were it not for the unfortunate vinyl roof (a necessity imposed by the inability of the paint of the era to cope with the slight flexing of the roof), it would visually be as close to perfect as any machine ever made.

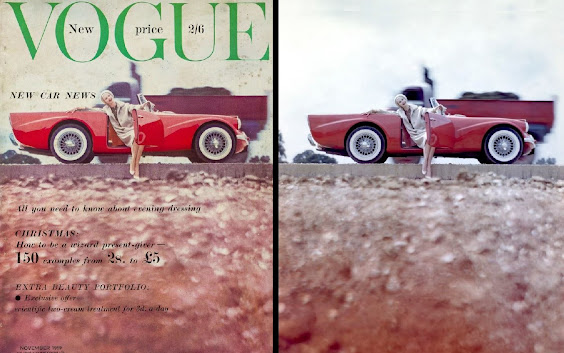

Using one of his trademark outdoor settings, Norman Parkinson (1913-1990) photographed model Suzanne Kinnear (b 1935) adorning a Daimler SP250, wearing a Kashmoor coat and Otto Lucas beret with jewels by Cartier. The image was published on the cover of Vogue's UK edition in November 1959.

Although Daimlers had, in small numbers, been imported into US for decades, after Jaguar purchased the company in 1960, there was renewed interest and the first model used to test the market was the small, fibreglass-bodied roadster, probably the most improbable Daimler ever and one destined to fail, doomed by (1) the quirky styling and (2) the lack of product development. It was a shame because what made it truly unique was the hemi-headed 2.5 litre (155 cubic inch) V8 which was one of the best engines of the era and remembered still for the intoxicating exhaust note. The SP250 was first shown to the public at the 1959 New York Motor Show and there the problems began. Aware the small sports car was quite a departure from the luxurious but rather staid line-up Daimler had for years offered, the company had chosen the pleasingly alliterative “Dart” as its name, hoping it would convey the sense of something agile and fast. Unfortunately, Chrysler’s lawyers were faster still, objecting that they had already registered Dart as the name for a full-sized Dodge so Daimler needed a new name and quickly; the big Dodge would never be confused with the little Daimler but the lawyers insisted. Imagination apparently exhausted, Daimler’s management reverted to the engineering project name and thus the car became the SP250 which was innocuous enough even for Chrysler's attorneys and it could have been worse. Dodge had submitted their Dart proposal to Chrysler for approval and while the car found favor, the name did not and the marketing department was told to conduct research and come up with something the public would like. From this the marketing types gleaned that “Dodge Zipp” would be popular and to be fair, dart and zip(p) do imply much the same thing but ultimately the original was preferred and Darts remained in Dodge’s lineup until 1976, for most of that time one of the corporation's best-selling and most profitable lines. The name was revived between 2012-2016 for an unsuccessful and unlamented compact sedan.

US market 2001 Jaguar Vanden Plas (X308). These were the only Jaguars factory-fitted with the fluted trim.

Decades later, US trademark law would again intrude on Jaguar’s Daimler business in the US. The company had stopped selling Daimlers in the US with the coming of January 1968 when the first trickle (soon to be a flood) of safety & emission regulations came into force, the explanation being the need to devote and increasing amount of by then scarce capital to compliance, meaning the marketing budget could no longer sustain small-volume brands & models. In Stuttgart, the Daimler-Benz lawyers took note and decided to reclaim the name, eventually managing to secure registration of the trademark and Daimlers have not since been available in the US. However, there was still clearly demand for an up-market Jaguar and so the Sovereign name (used on Daimlers between 1966-1983) was applied to Jaguar XJ sedans which although mechanically unchanged were equipped with more elaborate appointments. Sales were good so the US market also received some even more luxurious Vanden Plas models and during the XJ’s X308 model run (1997-2003), the VDP cars were fitted with the fluted grill and trunk-lid trim as an additional means of product differentiation. It would be the last appearance of the flutes in North America.

1999 Jaguar XJ8 Vanden Plas (US market model).

Although some might dismiss the interior fittings of the Vanden Plas models as “bling”, there were nice touches. The ones based on the X308 series Jaguar XJ (1997–2003) featured the fold-down picnic-tables so beloved by English coachbuilders but rather than the usual burl walnut veneer, the pieces were solid timber. The factory seems never to have discussed the rationale but it may be it was cheaper to do it that way, the veneering process being labor-intensive.

Pim Fortuyn in Daimler V8, February 2002 (left), paramedics attending to him at the scene of his assassination a few paces from the Daimler, 6 May 2002 (he died at the scene) (centre) and the car when on sale, Amsterdam, June 2018 (right).

Jaguar

became aware the allure of the flutes was real when it emerged a small but

profitable industry had emerged in the wake of the company also ceasing to use

the Daimler name in European markets; by the 1990s, it was only in the UK,

Australia & New Zealand that they were available. However, enterprising types armed with

nothing more than a list of Jaguar part-numbers had created kits containing the

fluted trim parts and the Daimler-specific badges, these shipped to dealers or

private buyers on the continent so Jaguar XJs could become “Daimlers”. The company took note and re-introduced the

range to Europe, the Netherlands a particularly receptive market. One notable owner of a real long wheelbase

(LWB) Daimler V8 (X308) was the Dutch academic and politician Pim Fortuyn

(1948-2002), assassinated during the 2002 national election campaign, by a

left-wing environmentalist and animal rights activist.

Lindsay Lohan with stainless steel Rolex Datejust (Roman numeral dial) with fluted white gold bezel.