Catfish (pronounced kat-fish)

(1) In ichthyology, any of the numerous mainly freshwater teleost fishes

of the order or suborder Nematognathi (or Siluroidei), characterized by barbels

around the mouth and the absence of scales, especially the silurids of Europe

and Asia and the horned pouts of North America.

(2) A wolffish of the genus Anarhichas.

(3) In casual use, any of various other fishes having a

fancied resemblance to a catfish.

(4) In slang, a person who assumes a false identity or

personality on the internet, especially on social media, usually with an intent

to deceive, manipulate, or swindle.

(5) To deceive, swindle, etc by assuming a false

identity or personality online.

(6) In casual use, any piece of machinery having a fancied resemblance to a catfish (applied often to cars with "gaping grills" ).

1605–1615: The construct was cat + fish. Dating from circa 700, cat was from the Middle

English cat or catte and the Old English catt

(masculine) & catte

(feminine). It was cognate with the Old

Frisian and Middle Dutch katte, the Old

High German kazza, Old Norse köttr, Irish cat, Welsh cath (thought derived from the Slavic kotŭ), the Russian kot and the Lithuanian katė̃; the Old French chat enduring. The curious Late

Latin cattus or catta was first noted in the fourth century, presumably associated

with the arrival of domestic cats but of uncertain origin. The Old English catt appears derived from the earlier (circa 400-440) West Germanic

form which came from the Proto-Germanic kattuz

which evolved into the Germanic forms, the Old Frisian katte, the Old Norse köttr,

the Dutch kat, the Old High German kazza and the German Katze, the ultimate source being the Late

Latin cattus.

The noun fish was from the pre-900 Middle English fish, fisch & fyssh, from the Old English fisc (fish), from the Proto-West Germanic fisk, from the Proto-Germanic fiskaz (fish). It was cognate with the West Frisian fisk, the Dutch vis, the Old Norse fiskr, the Danish fisk, the Norwegian fisk, the Gothic fisks, the Swedish fisk and the German Fisch, the ultimate source probably the primitive Indo-European peysḱ (fish) & pisk (a fish) although there are etymologist who speculate, on phonetic grounds, that it may be a north-western Europe substratum word. It was akin to the Latin piscis, the Irish verb iasc, the Middle English fishen and the Old English fiscian, cognate with the Dutch visschen, the German fischen, the Old Norse fiska and the Gothic fiskôn. The verb fish was from the Old English fiscian (to fish, to catch or try to catch fish). It was cognate with the Old Norse fiska, the Old High German fiscon, the German fischen and the Gothic fiskon. The catfish seems to have gained its name early in the seventeenth century following the practice adopted for the Atlantic wolf-fish, noted for its ferocity, the catfish picking up its moniker apparently because of the "whiskers" although the "purring" sound it sometimes makes upon being taken from the water has (less convincingly) been suggested as the origin; most zoologists and etymologists prefer the whiskers story while noting the correct name for the appendages is barbels. Catfish & catfishing are nouns & verbs, catfisher is a noun, catfished is a verb and catfishlike & catfishesque (the latter listed by some as non-standard) are adjectives, the noun plural is catfish or catfishes.

Strictly speaking, the choice of the plural form (catfish or catfishes) should folow the usual convention in matters ichthyological. The plural of "fish" is an illustration of the inconsistency of English. As the plural form, “fish” & “fishes” are often (and harmlessly) used interchangeably but in zoology, there is a distinction, fish (1) the noun singular & (2) the plural when referring to multiple individuals from a single species while fishes is the noun plural used to describe different species or species groups. The differentiation is thus similar to that between people and peoples yet different from the use adopted when speaking of sheep and, although opinion is divided on which is misleading (the depictions vary), the zodiac sign Pisces is referred to variously as both fish & fishes. So, it is correct to speak of multiple catfish if all are of the same species but to use "catfishes" if there's a mix. In cooking (the frequent collective being "catfish stew"), or any reference to use as food (or bait), the plural is without exception "catfish".

The modern term catfishing describes a type on nefarious on-line activity in which a person uses information and images, typically taken from others, to construct a new identity for themselves. In the most extreme examples, a catfisher can steal and assume another individual’s entire identity, enabling the possibility of using the fake persona to engage in fraud or other illegal activities. Catfishing attacks may be targeted or opportunistic and have long been common on dating sites. One niche activity is where only a few (or legally insignificant) elements are involved (usually in an attempt to tempt younger subjects on dating sites) and there is no attempt to engage in illegal activity; this has been called kitten fishing. There is nothing new in the concept of catfishing, cases documented in the literature for centuries, the ubiquity of the internet just making such scams both easier to execute and detect so in its latest use, "catfish" is one of those terms which achieved critical linguistic mass because of the adoption of newly available technology, joining those words which have for centuries been either coined or re-purposed in a kind of technological determinism. The term in this context is derived from the 2010 American documentary Catfish, which concerned a 26 year old man who, thinking he was building an on-line relationship with a 19 year old woman, discovered his digital interlocutor was actually a married women of 40. The documentary (and thus the on-line behavior) gained the name from a mention the woman's husband made when comparing his wife’s conduct to the myth that it was once the practice to include one or more catfish in the tank when shipping live cod, the rationale said to be the cod would remain active in the presence of codfish whereas if shipped alone, would become pale and lethargic, reducing the quality of the flesh. The source of the myth was the 1913 psychological novel Catfish by Charles Marriott (1869-1957), the fanciful story repeated that same year by Henry Wooded Nevinson (1856-1941) in his political treatise, Essays in Rebellion. The emergence on the internet of "catfishing" begat "sadfishing, the technique (most associated with the emo) of posting about one's unhappiness or emotional state ("devastated" an emo favorite) on social media platforms, the object being to attract attention and sympathy; it's regarded in many cases as the seeking of "validation".

Etymologically unrelated (although not wholly dissimilar in practice) was the earlier internet slang "phishing" which described a kind of social engineering in which an attacker sends a deceptive message designed to trick a person into revealing sensitive information or induce them in some way to install malicious software such as key-stroke grabbers or ransomware. Phishing is a leetspeak variant of "fishing" which compares the digital activity to actual angling, the idea being the casting of lines with lures in the hope there will be bites at the bait. The first known reference to phishing dates from 1995 but there was apparently an earlier mention in the magazine 2600: The Hacker Quarterly, the word coined following the earlier phreaking. Phishing has for years been the most common attack performed by cybercriminals.

The "Catfish Cars"

Catfish and some cars they inspired.

First seen on a few eccentric examples during the 1930s, the distinctive, if not always pleasing “catfish look” emerged on volume production automobiles during the 1950s. Even then the look was a stylistic curiosity but it was an age of extravagance and among the macropteric creations of the era, the catfish cars represented just one of many directions the industry could have followed. Nor was the catfish look wholly without engineering merit, the low bonnet (hood) line improving aerodynamic efficiency, the wide, gaping aperture of the grill permitting adequate air-flow for engine cooling with headlamps able still to satisfy regulatory height requirements. Classic examples of catfish styling includes the original Citroen DS (top left), the Packard Hawk (top centre) and the Daimler SP250 (top right).

Daimler SP250 (1959-1964).

The Daimler SP250 was first shown to the public at the 1959 New York Motor Show and there the problems began. Aware the little sports car was quite a departure from the luxurious but rather staid lineup Daimler had for years offered, the company had chosen the pleasingly alliterative “Dart” as its name, hoping it would convey the sense of something agile and fast. Unfortunately, Chrysler’s lawyers were faster still, objecting that they had already registered Dart as the name for a full-sized Dodge so Daimler needed a new name and quickly; the big Dodge would never be confused with the little Daimler but the lawyers insisted.

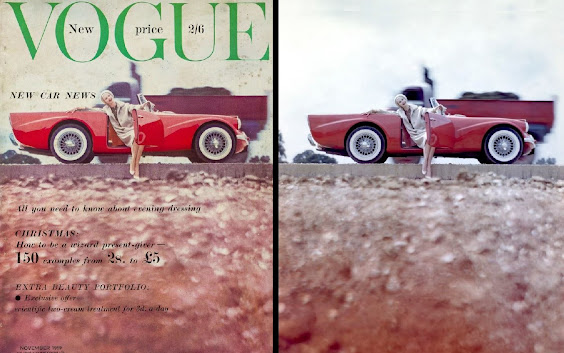

Using one of his trademark outdoor settings, Norman Parkinson (1913-1990) photographed model Suzanne Kinnear (b 1935) adorning a Daimler SP250, wearing a Kashmoor coat and Otto Lucas beret with jewels by Cartier. The image was published on the cover (left) of Vogue's UK edition in November 1959, the original's (right) color being "enhanced" in pre-production editing. The "wide" whitewall tyres were a thing at the time, even on sports cars and were a popular option on US market Jaguar E-Types (there (unofficially) called XK-E or XKE) in the early 1960s.

Imagination apparently exhausted, Daimler’s management reverted to the engineering project name and thus the car became the SP250 which was innocuous enough even for Chrysler's attorneys and it could have been worse. Dodge had submitted their Dart proposal to Chrysler for approval and while the car found favor, the name did not and the marketing department was told to conduct research and come up with something the public would like. From this the marketing types gleaned that “Dodge Zipp” would be popular and to be fair, dart and zip(p) do imply much the same thing but ultimately the original was preferred and Darts remained in Dodge’s lineup until 1976, for most of that time one of the corporation's best-selling and most profitable lines. The name was revived between 2012-2016 for an unsuccessful and unlamented compact sedan.

Daimler’s SP250 didn’t enjoy the same longevity, the last of the 2654 produced in 1964, sales never having approached the projected 3000 per year, most of which were expected to be absorbed by the US market. The catfish styling probably didn’t help, a hint being the informal poll taken at the 1959 show when the thing was voted “the ugliest car of the show” but under the skin of the ugly duckling was a virile swan. The heart of the SP250 was a jewel-like 2.5 litre (155 cubic inch) hemi-headed V8 which combined the structure of Cadillac’s V8 with advanced cylinder heads which owed much to those of the Triumph Thunderbird motorcycle engine. Indeed, the designer, Edward Turner (1901–1973), owned a Cadillac and was responsible for the Triumph heads so the influences weren’t surprising and the little engine had an interesting gestation. It was Turner’s first car engine and so tied was he to the principles which had proved so successful for his motorcycles that the original concept was air-cooled and fed by eight carburetors. Automotive reality however prevailed and what emerged was a compact, light (190 KG (419 lb)), water-cooled V8 with the inevitable twin SU carburetors, the project yielding also an only slightly bulkier (226 KG (498 lb)) 4.6 litre (278 cubic inch) version which would be tragically under-utilized by a British motor industry which could greatly have benefited from a wider deployment of both instead of some engines which proved pure folly. The Daimler V8s are notable too for their intoxicating exhaust notes, perhaps not a critical aspect of engineering but one which adds much to the pleasure of ownership.

Under-capitalized and lacking the funds needed to revitalize

their dated range, let alone develop new high-volume models, the SP250 was

created on a shoestring budget, the body built in the then still novel

fibreglass, not by deliberate choice but because the tooling and related

production facilities could be fabricated for a fraction of the cost had steel

or aluminum been used. It also lessened

the development time and promised a simpler and cheaper upgrade path in the

future but also brought problems of its own.

New to the material, Daimler’s engineers were confronted with many of

the same problems which Chevrolet encountered during the early days of the

Corvette, issues which even with the vast resources of General Motors, proved

troublesome. Other than the fibreglass

body, the SP250 was technologically conventional, using a chassis little

different from that of the Triumph TR3, built in a 14 gauge box section with

central cruciform bracing. The chassis

was designed to be light and that was certainly achieved but at the cost of

structural rigidity, again an issue of the use of fibreglass, the engineers (in

pre-CAD times) under-estimating the stiffness which would be demanded in a

structure without metal panels further to distribute the loadings.

The lack of sufficient torsional rigidity meant the SP250s were beset with the same teething problem as the first Corvettes: the fibreglass panels could become crazed or even crack and, most disconcertingly, doors were prone to springing open during brisk cornering and the bonnet (hood) sometimes popped open as the body flexed at high speed. The SP250 was a genuinely fast car so these were not minor issues. Still, there was much to commend the SP250. Wind-up windows and the availability of an automatic transmission sound hardly ground-breaking but they were an innovation unknown on the MG, Triumph and Austin-Healy roadsters of the time and the V8 was unique. The suspension was conventional but competent, an independent front end with upper and lower arms, coil springs, and telescopic shock absorbers while the rear used semi-elliptic leaf springs with lever arm shock absorbers. The unassisted cam and peg system steering lacked the precision the Italians achieved even without using a rack and pinion system but, aided by a larger than usual steering wheel, it offered a reasonable compromise for the time although at low speed it was far from effortless. More commendable were the brakes. The four-wheel discs had no power assistance but the SP250 was a light car and the servo systems of the time, lacking feel and impeding the progressiveness inherent in the design of the early discs, meant unassisted systems were preferable for sports cars although, efficient and fade-free though they were, an emergency stop from speed did demand high pedal effort. One curiosity in the configuration was the bumper bars. Considering the issue bumpers would become in the 1970s, that they were once optional is an indication of how different the regulatory environment was at the time. The A spec SP250s had no bumpers as standard equipment but were fitted at the front with what are sometimes mistakenly called nerf-bars but are actually “bumperettes” although the English seem to like “whiskers”. At the rear were over-riders attached to nerf-bars. The B spec models didn’t include these but, like the A spec, the full bumpers were an optional extra and this setup was continued for the C spec. The SP250s used by the British Metropolitan Police as high speed pursuit cars always had the optional bumpers because of the need to mount the warning bell and auxiliary spotlight.

So, developed to the extent possible with the resources available, production began in 1959, shortly before the Birmingham Small Arms Company (BSA) announced the sale of Daimler to Jaguar. Jaguar, attracted by Daimler’s extensive manufacturing facilities and its skilled workforce regarded most of the Daimler range as antiquated but allowed some production to continue although their engineers decided the chassis of the SP250 needed significant modifications to improve rigidity. The strengthening was undertaken and the revised cars became known as the “B” models, the original 1959-1960 versions retrospectively labeled as A-Spec. The changes were actually not extensive, a steel box section hoop added to connect the windscreen pillars, two steel outrigger sill beams along each side of the chassis, complimented with a couple of strategically placed braces. The stiffer structure solved the problems and improved the driving experience, the B-spec cars produced between 1960-1963. A subsequent upgrade, dubbed C-spec included some features such as a cigar lighter and a heater/demister and in this form, the cars remained in production until 1964.

Daimler SP252 prototype (1964)

Unfortunately, Jaguar was never enthusiastic about

Daimler except as a badge which could be used on up-market Jaguars sold at a

nice profit. However, whatever the

opinions of the catfish styling, the SP250 had proved itself in motorsport and, capable of a then impressive 122 mph (196 km/h), had been used as a high-speed pursuit vehicle by a number of police forces,

interestingly usually with an automatic transmission, the choice made in the

interest of reduced maintenance, a conclusion rental car companies would soon

reach. For that reason, the potential

was clear and Jaguar explored a way to extend the appeal with a restyled

body. The result was the SP252, rendered

still in fibreglass but now more elegantly done, hints of both the MGB and

Jaguar E-Type (XK-E) while the rear owed some debt to Aston Martin’s DB4. Aesthetically accomplished though it was, economic

reality prevailed. The factory was tooled-up to produce no more than 140 of the V8 engines each week, demand for which

was already exceeding supply since it had been offered in the Jaguar Mk2-based

Daimler 2.5 (later 250) saloon and Jaguar lacked the production capacity even to make enough E-types to meet demand. Given

that and the engineering resources it required to devote to the new V12

engine and the XJ6 saloon for which it was intended, another relatively

low-volume project couldn’t be justified.

Jaguar missed an opportunity by not making better use of the Daimler V8s. The smaller unit could have been enlarged to 2.8 litres to take advantage of the taxation rules in continental Europe and in the XJ would have been a more convincing powerplant than the 2.8 XK six which was always underpowered and prone to overheating. When fitted to a prototype Jaguar Mark X, the 4.6 litre V8 had proved outstanding and, easily able to be expanded beyond five litres, it would have been ideal for the lucrative US market and the thought of a 4.6 V8 E-Type (XKE) remains tantalizing. Unfortunately, Jaguar was besotted with the notion of the V12 and it wasn't until the 1990s they admitted what was needed was a 4-5 litre V8, the very thing they'd acquired with the purchase of Daimler in 1960.

Produced between 1955-1975, the Citroën DS, although long regarded as something quintessentially French, was actually designed by an Italian. In this it was similar to French fries (actually invented in Belgium) and Nicolas Sarközy (b 1955; President of France 2007-2012), who first appeared in the same year as the shapely DS and was actually from here and there. It was offered as the DS and the lower priced, mechanically simpler ID, the names apparently an deliberate play on words, DS in French pronounced déesse (goddess) and ID idée (idea). The goddess nickname caught on though idea never did; a curiously configured version built exclusively for the UK market was called the DW which appears to have meant nothing in particular. The frontal aspect, combined with the efficiency of the rest of the body, delivered outstandingly good aerodynamics but the catfish look was tempered a little because the low, gaping grill associated with the motif well-concealed, reputedly because the ancient engine, a long-stroke, agricultural relic of the 1930s, produced so little power there wasn’t enough surplus energy to induce overheating, the need for a cooling flow of air correspondingly low. That’s wholly apocryphal but later progress in design anyway softened the catfish effect. It was most obvious on the series 1 cars (top) which were made between 1955-1962. The Series 2 changes (1964-1967; centre) were effected further to improve aerodynamics and permitted also some increase to the airflow ducted for interior ventilation; the changes in appearance were said to be incidental to the process. The catfish look vanished entirely when the series 3 cars (bottom) were introduced in 1967.

Now with four headlamps mounted behind glass canopies, the shape of which was integrated into the front fenders (top left), the arrangement was noted for the novelty of the inner set of lens being controlled by the steering (top right), the light thus being projected “around the corner” in the direction of travel, swiveling by up to 80°. It was a simple, purely mechanical connection and the idea had during the 1930s used with auxiliary driving or fog-lights and the central (Cyclops) unit on the abortive Tucker Torpedo (1948) had been configured the same way but the DS was the first car to use adaptive headlights in volume. Both the covers and the turning mechanism fell afoul of US regulations (lower left) so there the lens were fixed and exposed. Another variation was in Scandinavia where miniature wipers were sometimes fitted to conform with local law. In the collector market, the small feature can add a remarkable premium to the value of a car, rare factory options highly sought.

1958 Packard Hawk

Fittingly perhaps, the gaping-mouth of the catfish style was applied to what proved one of the last gasps for Packard, a storied marque with roots in the nineteenth century which in the inter-war years had been one of the most prestigious in the US and it had been the sound of the V12 Packards which inspired Enzo Ferrari (1989-1988) to declare Una Ferrari è una macchina a dodici cilindri (a Ferrari is a twelve cylinder car). The appeal was real because it was a 1936 Packard phaeton Standard Eight which comrade Stalin (1878-1953; Soviet leader 1924-1953) used as his parade car and the ZiS-115 limousine (1948-1949 and based on the ZiS 110 (1946-1958), all better known in the West as ZILs) he used in his final years was a reversed-engineered (ie copy) version of the 1942 Packard. Reverse-engineering was a notable feature of Soviet industry and much of its post-war re-building of the armed forces involved the process, exemplified by the Tupolev Tu-4 heavy bomber (1947) which was a remarkably close copy of the US Boeing B-29 (1942). Other countries also adopted the practice which in some places continues to this day for mot civilian and military output. After spending World War II engaged in military production, notably a version of the Merlin V12 aero-engine built under license from Rolls-Royce, Packard emerged in 1945 in sound financial state but found the new world challenging, eventually in 1953 merging with fellow struggling independent, Studebaker. Beset with internal conflicts from the start, things went from bad to worse and after dismal sales in 1958-1959 of the final Packards (which were really modified Studebakers and derided by many as "Packardbakers"), the Packard brand was retired with the coming of 1959. The Studebaker-Packard Corporation in 1962 reverted to again become Studebaker but it was to no avail, the last Studebaker being produced in 1967.

The mashup of period styling motifs (fins, dagmars, curved glass, scallops & scoops) on the 1958 Packard was not untypical in the era and the catfish treatment at the front was really the most restrained part of the package.

The origins of Packard’s swansong, the Hawk, lay in a 1957

Studebaker Golden Hawk 400 which was customized in-house for executive

use. The front end and bonnet (hood)

were rendered in fiberglass, eliminating the familiar upright grille and small

side inlets which were replaced with the low, wide air intake so characteristic

of the catfish look. Covering all bases, for those unconvinced by the catfish look, a pair of modest (by Cadillac standards) dagmars were added. Because the engine

was supercharged, like the Studebaker, the hood included a bulge but because

of the lower lines, it rose higher on the Packard. Lacking the funds to create anything better,

the Hawk was approved for production as a standard 1958 model but it was from

the start doomed. It was expensive and its

debut coincided with the recession of that year when all auto-makers suffered

downturns but, with the rumors swirling of Studebaker-Packard's impending demise,

Packard suffered more than most and only 588 Hawks were built.

1958 Packard

Packard’s rather plaintive swansong was another set of cobbled-together

Packardbakers, available as a two-door hardtop and a four-door sedan or wagon. In 1958, fins were a thing at the rear but

what really exited the stylists was that quad headlamps were now permitted in

all 48 states. Unlike the majors

however, the corporation had no funds to re-tool body dies to accommodate

the change so hurriedly, fibreglass pods were created which when fitted, looked

as tacked-on as they really were. Also

tacked on were the new fins which sat atop the old although these were at

least genuine steel rather than fibreglass.

1958 Chrysler Royal (AP2) and 1960 Chrysler Royal (AP3) (Australian)

They were also definitely always standard equipment on all the Packards, unlike the 1958 Australian Chrysler Royal (AP2) which featured similar appendages grafted to pre-existing fins, Chrysler listing them as an optional extra called "saddle fins". However, no Royal apparently was sold without saddle fins attached so either (1) they were very popular option or (2) Chrysler changed their mind after the promotional material was printed and decided to invent "mandatory options", a marketing trick Detroit would soon widely (and profitably) adopt. In 1960, the Australians also solved the problem of needing to add quad headlamps without either a re-tool or plastic pods, changing instead the grill and mounting the lights in a vertical stack, an expedient Mercedes-Benz had recently used to ensure their new W111 (Heckflosse) sedans (1959-1968) satisfied US legislation.