Condign

(pronounced kuhn-dahyn)

(1) Well-deserved;

fitting; suitable; appropriate; adequate (usually now of punishments).

(2) As condign

merit (meritum de condign), a concept

in Roman Catholic theology signifying a goodness that has been bestowed because

of the actions of that person

(3) As “Project Condign”, a (now de-classified) top-secret study into UFOs (unidentified flying objects, known also as UAPs (unidentified aerial phenomenon)) undertaken by the UK government's

Defence Intelligence Staff between 1997-2000.

1375–1425:

From the late Middle English condign,

& condigne (well-deserved,

merited) from the Anglo-French, from the Old French condign (deserved, appropriate, equal in wealth), from the Latin condignus (wholly worthy), the construct

being con- + dignus (worthy; dignity), from the primitive from Indo-European root

dek- (to take, accept). . The

Latin con- was from the Proto-Italic kom- and was related to the preposition

cum (with). In Latin, the prefix was

used in compounds (1) to indicate a being or bringing together of several

objects and (2) to indicate the completeness, perfecting of any act, and thus

gives intensity to the signification of the simple word. It's believed the UK's MoD (Ministry of Defence) chose

“Project Condign” as the name for its enquiry into UFOs (1) because (1) the

military like code names which provide no obvious clue about the nature of the

matter(s) involved and (2) in the abstract, it conveyed the notion the investigation would provide a measured, proportionate, and sober assessment of

the issue (ie a response commensurate with the evidence, not an endorsement of unsubstantiated

speculation or explanations delving into the extra-terrestrial or supernatural). Condign is an adjective, condignity &

condignness are nouns and condignly is an adverb; the noun plural is condignities.

In Middle

English, condign was used of rewards as well as punishment, censure etc, but by

circa 1700 it had come to be applied almost exclusively of punishments, usually

in the sense of “deservedly severe”.

Thus used approvingly, the adjectival comparative was “more condign”,

the “superlative “most condign”. That

means the synonyms included “fitting”, “appropriate”, “deserved”, “just”, “merited”

etc with the antonyms being “excessive”, “inappropriate” & “undeserved”,

the latter set expressed by the negative incondign. However, a phenomenon in the language is that

words which have, since their use in Middle English, undergone a meaning shift

so complete as to render the original meaning obsolete, can in ecclesiastical

use retain the original sense. In the theology

of the Roman Catholic Church, meritum de

condigno (condign merit) is that due to a person for some good they have

done. As a general principle, it’s held

to be applied to “merit before God”, the Almighty binding Himself, as it were,

to reward those who do his will; a kind of holy version of social contract

theory. Among the more simple aspects of

Christian theology, the conditions for condign merit are: (1) holding oneself

in a state of grace and (2) performing morally good actions. Not transferable, the beneficiary can be only the

person who performs the good act with condign merit based on the revealed fact

that God has promised such a reward and as a reward it’s accumulative, each

individual condignly meriting an increase of the virtue of faith by every act

of faith performed in the state of grace.

Pragmatic parish

priests probably are inclined to explain condign merit as a way of

encouraging kindness to others (linking it to the notion of “do unto

others as you would have them do unto you” which is the essence of the

Christian morality) but the theologians stress the significance of meritum de condign is it refers to merit

based on justice rather than mere generosity of spirit. It seems a fine distinction and doubtless is, both to doer of deed and beneficiary but, because the act

is performed in a state of grace and is proportionate by God’s own ordinance to

the reward promised, it’s a genuine claim based on justice, God rewarding such

acts not out of mere benevolence but because freely He has so bound himself.

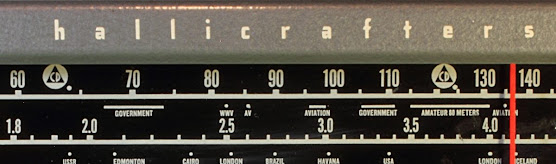

Project Condign: Unidentified Aerial Phenomena in the UK Air Defence Region (in three volumes). It turns out they're not out there.

The

theologians manage to add layers by stressing meritum de condign can apply only to an individual in a state of

grace (and thus justified and acting under sanctifying grace); without grace,

no strictly meritorious claim on God is possible. God may still be generous, but the reward

will be granted under another head of power.

Additionally, the act must freely be performed and motivated by charity

(love of God); mere kindness in the absence of this love not reaching the

threshold. Unusually, the reward of

condign merit is by virtue of a Divine promise, the “justice” not “natural” but

“covenantal”, God having imposed upon himself the obligation of reward, therefore

it would be incongruum (from the Latin, an inflection of incongruus (inconsistent, incongruous, unsuitable)) for him not to do so and unlike the state in

the social contract, God regards Himself truly as bound and the proportion is by

divine ordination (ie the proportion between act and reward exists only because

God has established it; it is not intrinsic to the act itself.

In certain

aspects, the comparison with later legal traditions is quite striking. Condign merit can apply variously to (1) an

increase in charity, (2) an increase of sanctifying grace and (3) heavenly

glory (eternal life), insofar as it is the consummation of grace already

possessed but crucially, even condign merit presupposes grace entirely: the

grace that enables the act is itself unmerited.

In other words, God and the church expect a certain basic adherence and

this alone is not enough to deserve condign merit. The companion term is meritum de congruo (congruous merit) in which a fitting

or appropriate reward may be granted but that will be based on God’s generosity

rather than being the self-imposed obligation that is condign merit. If searching for a metaphor, condign merit

may be imagined as something given according to a salutatory schedule while congruous

merit is more like an ex gratia (a learned borrowing from Latin ex grātiā (literally “out of grace”))

payment (a thing not legally required but given voluntarily).

Santo Tomás de Aquino (Saint Thomas Aquinas, 1476) ,egg tempera on poplar panel by Carlo Crivelli (circa 1430-circa 1495) in a style typical of religious portraiture at at time when some

Renaissance painters were still much influenced by late

Gothic decorative sensibility. This piece was from the upper tier of a polyptych (multi-panelled altarpiece) which Crivelli in 1476 completed for the high altar of the church of San Domenico, Ascoli Piceno in the Italian Marche.

Even among

the devotional, in the twenty-first century all that may sound mystical or a

tiresome theological point but there was a time in Europe when many much were

concerned about avoiding Hell and going to Heaven with the Medieval church was

there to explain the rules and mechanisms.

The carefully crafted distinction was made by the Italian Dominican

friar, philosopher & theologian Saint Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) in the Summa Theologiae (Summary of Theology, a

work still unfinished by the time of the author’s death) and re-affirmed, essentially unaltered, during Session

VI (Decree on Justification) of the Council of Trent (1545-1563). In modern practice, priests don’t much bother

their flock with Aquinas’s finely honed thoughts and instead exhort them to acts

of kindness, rather than dwelling too much on abstractions like whether God

will reward them by virtue of obligation or generosity, the important message

being the Almighty remains sole source of both grace and reward, thus the

importance to keep in a state of grace with him.

Google ngram (a quantitative and not qualitative measure): Because of the way Google harvests data for their ngrams, they’re not literally a tracking of the use of a word in society but can be usefully indicative of certain trends, (although one is never quite sure which trend(s)), especially over decades. As a record of actual aggregate use, ngrams are not wholly reliable because: (1) the sub-set of texts Google uses is slanted towards the scientific & academic and (2) the technical limitations imposed by the use of OCR (optical character recognition) when handling older texts of sometime dubious legibility (a process AI should improve). Where numbers bounce around, this may reflect either: (1) peaks and troughs in use for some reason or (2) some quirk in the data harvested.

So while it

has always implied “deserved”, Roman Catholic theologians thus still use

“condign” in the context of a “reward for goodness” but in secular use it has

for centuries been associated only with punishment and, the more fitting the

sentence, the more condign it’s said to be.

As Christianity in the twentieth century began its retreat from

Christendom, condign became a rare word and some now list it as archaic

although as late as 1926, in A Dictionary

of Modern English Usage, Henry Fowler (1858–1933), no great friend of “decorative

words” and “elegant variations” though it still worth a descriptive (and

cautionary entry: “Condign meant originally ‘deserved’ and could be used in

many contexts, with praise for instance as well as with punishment. It is now used only with words equivalent to

‘punishment’, and means deservedly severe, the severity being the important

point, and the desert merely a condition of the appropriateness of the word;

that it is an indispensable condition, however, is shown by the absurd effect

of: ‘Count Zeppelin’s marvellous voyage through the air has ended in condign

disaster’”.

Quite what

old Henry Fowler would have made of the way the language of Shakespeare and Milton is used on social

media and the like easily can be imagined but he’d have been heartened to learn

the odd erudite soul still finds a way to splice something like “condign” into

the conversation. One, predictably, was

that scholar of Ancient Greek, Boris Johnson (b 1964; UK prime-minister

2019-2022) who, during his tumultuous premiership, needed to rise from his

place in the House of Commons to tell honourable members that the withdrawal of

the Tory Party whip (“withdrawal of the party whip” a mechanism whereby a MP (Member

of Parliament) is no longer recognised as a member of their parliamentary

party, even though in some cases they continue for most purposes to belong to

the party outside the parliament) from a member accused of sexual misconduct

was “condign punishment”.

Mr Johnson

was commenting on the case of Rob Roberts (b 1979; MP for Delyn 2019-2024) and

while scandal is nothing novel in the House of Commons (and as the matter of Lord

Peter "Mandy" Mandelson (b 1953) illustrates, nor is it in the upper

house), aspects of the Roberts case were unusual. In 2021, an independent panel, having found

Mr Roberts sexually had harassed a member of his staff recommended he should be

suspended from parliament for six weeks.

The panel found he’d committed a “serious and persistent breach of the parliament’s sexual

misconduct policy” and although the MP had taken “positive steps”,

he’d demonstrated only “limited insight into the nature of his misconduct”,

the conclusion being there remained concerns “he does not yet fully understand the

significance of his behaviour or the full nature and extent of his wrongdoing.” Politicians sexually harassing their staff is

now so frequent as to be unremarkable but what attracted some interest was that

intriguingly, Mr Roberts had identified the problem and it turned out to be the

complainant. When alone together in a

car on a constituency visit, the MP had said to him: “I find you very attractive and alluring and

I need you to make attempts to be less alluring in the office because it's

becoming very difficult for me.”

So it was Mr Roberts who really was the victim and the complainant

clearly made an insufficient effort to become “less alluring”

because the MP later told the man the advance he had made in the car was “something I would

like to pursue, and if you would like to pursue that too it would make me very

happy”. From there, things got

worse for the victim (in the sense of the complainant, not the politician).

Official portrait of Rob Roberts, the former honourable member for Delyn.

Mr Roberts

had “come out” as gay after 15 years of marriage, the panel noting he’d been “going through

several challenges and significant changes in his personal life”,

adding these “do

not excuse his sexual misconduct”.

Despite his announcement, he also propositioned young female staff

members (perhaps he should have “come out” as bisexual), suggesting to one they

might: “fool

around with no strings”, assuring her that while he “…might be gay… I

enjoy … fun times”. In April 2021 the Conservative (Tory) Party had announced

that the MP had been "strongly rebuked", but would not lose the

whip. Apparently, at the time, it was thought sufficiently condign for him to “undertake

safeguarding and social media protection training”. The next month however, the panel handed down

its recommendations and he was “suspended from the services of the house for six weeks”,

subsequently losing the Tory whip and had his party membership suspended. In a confusing coda, after (controversially)

returning to the Commons in July 2021, he was re-admitted to the party in October

2021 but was denied the whip, requiring him to sit as an independent until the

end of his term. In the 2024 general

election, he stood as an independent candidate in the new constituency of Clwyd

East, coming last with 599 votes and losing his deposit. Privately as well as politically, life for Mr

Roberts has been discursive. After in

May 2020 tweeting he was gay and separating from his wife, in 2023, he

re-married.

The word

even got a run on Rupert Murdoch’s (b 1931) Fox News, an outlet noted more for

short sentences, punchy words and repetition than words verging on the archaic but

on what the site admitted was a “slow news day”, took the opportunity to skewer Jay

Robert “J.B. Pritzker (b 1965, (Democratic Party governor of US state of

Illinois since 2019), noting the part the wealth of the “billionaire heir to the Hyatt hotels fortune”

had played in defeating a Republican opponent (it couldn’t resist adding that “money in politics”

was something crooked Hillary Clinton (b 1947; US secretary of state 2009-2013)

“could tell

you more about”). Fox News’s

conclusion was “…the

shamelessness and even braggadocio with which Pritzker sought to buy the

governorship could be a harbinger of things to come. But, we suppose, having to serve as governor

of Illinois is condign punishment for the offense…”

In happier times: But wherever

he is in the world, he remains my best pal!

Mandy’s (pictured here in dressing gown, tête-à-tête with Jeffrey Epstein) entry in the now infamous "birthday book", assembled for the latter’s 50th birthday in 2003.

The matter

of condign punishment has in Westminster of late been much discussed because of

revelations of the squalid behaviour of Mandy and his

dealings with convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein (1953–2019). Undisputedly, one of politics great networkers, Mandy’s long career in the Labour Party was

noted not for any great contribution to national life (although he did good work in the project which was "New Labour" but whether he now should regard that a proud boast or admission of guilt he must decide) or achievements in policy development but blatant self-interest, conflicts of interest and repeated recovery from scandal; twice he was forced to resign from cabinet

because of matters classed as “conflict of interest” and his whole adult life

has been characterized by seeking association with rich men who, for whatever

reason, seem to become anxious to indulge his desire to receive generous hospitality and large sums of

cash. Sir Tony Blair (b 1953; UK

prime-minister 1997-2007), clearly seeing talent where many others did not, was

most forgiving of Mandy’s foibles, twice re-appointing him to cabinet after

decided a longer exile would be most incondign and famously once observed his "mission to transform the Labour party would not be complete until it had learned to love Peter Mandelson." Even Gordon Brown (b 1951; UK prime-minister 2007-2010) who is believed

to have existed in a state of mutual loathing with Mandy, was by 2008 in such

dire political straits he brought him back to cabinet, solving the problem of

finding a winnable seat in the Commons by appointing him to the upper chamber,

the House of Lords. While the presence

of the disreputable in the Lords has a tradition dating back centuries, it was

thought a sign of the times that Brown “ennobling a grub like Mandelson” to take a seat in the house, where once sat Wellington, Palmerston and Curzon, attracted

barely an objection, so jaded by sleaze had the British public become.

Still, even

by the standards of Mandy’s troubled past, what emerged from the documents

released by the US DoJ (Department of Justice) was shocking. Not only did it emerge Mandy had lied about

the extent of his connections with Epstein but it became clear they had,

despite his repeated denials, continued long after Epstein’s 2008 conviction in

Florida on charges of soliciting and procuring a minor for prostitution for

which he received an 18 month sentence. So

well connected in the Masonic-like UK Labour party was Mandy (and there have

been amusing theories about how he has maintained this influence), it might

have been possible to stage yet another comeback from that embarrassment but

his life got worse when it was revealed large sums of cash had been passed to

him (or the partner who later became his husband) by Epstein, transactions made

more interesting still when it emerged Mandy appears to have sent to Epstein

classified files to which he gained access by virtue of being a member of

cabinet. More remarkable still was Mandy,

while a cabinet minister, appearing to operate as a kind of lobbyist in matter

of interest to what was described as: “Mr Epstein and his powerful banking friends”.

In happier times, left to right: Tony Blair, Gordon Blair & Mandy (left) and the mean girls: Karen Smith (Amanda Seyfried, b 1985), Gretchen Wieners (Lacey Chabert, b 1982) & Regina George (Rachel McAdams, b 1978) (right).

In the early 1990s, detesting the Tory government, the press were fawning in their admiration and dubbed the New Labour trio "the three musketeers" but they came also to be called: "the good, the bad and the ugly, a collective moniker which may be generous to at least one of them. There is no truth in the rumor the threesome provided the template for the personalities of the "plastics" in Mean Girls (2004, right) although the idea is tempting because both photographs can be deconstructed thus: Tony & Karen (sincere, well meaning, a bit naïve); Gordon & Gretchen (insecure, desperately wanting to be liked) and Mandy & Regina (evil and manipulative).

All this

was revealed in E-mail exchanges during the GFC (Global Financial Crisis) which

unfolded between 2008-2012 after the demise of US financial services firm Lehman

Brothers (1850-2008), Mandy giving Epstein “advance notice” the EU (European Union (1993)),

the multi-national aggregation which evolved from the EEC (European Economic

Community), the Zollverein formed in 1957) would be providing (ie “creating”) a

€500bn “bailout”

to prevent the collapse of the Euro (the currency used by a number of EU

states). Those familiar with trading on

the forex (foreign exchange) markets will appreciate the value of such secret

information and, given the trade in global currency dwarfs that in equities,

commodities and such, the numbers (and thus the profits and losses) are big. Pleasingly, in the manner commercial

arrangements often are, it was a two-way trade, representations to the UK and

US Treasuries arranged in both directions.

Mandy also

acted as Epstein’s advisor about “back channel” ways to influence government

policy (ie the government of which he was at the time serving in cabinet) and political

scientists probably would concede his advice was sage; he suggested to Epstein

he should arrange for the chairman of investment bank J.P. Morgan to “mildly

threaten” the UK’s chancellor of the exchequer (the finance minister). What a cabinet minister is by convention (and

implied in various statures) obliged to do is promote and defend government

policy while assisting in its execution; should they not agree with that policy,

they must resign from government. Clearly,

Mandy decided what is called “cabinet solidarity” was a tiresome inconvenience

and in an attempt to change cabinet’s policy on a bankers’ bonus tax, made his

suggestion which Mr Epstein must have followed because J.P. Morgan’s Jamie

Dimon (b 1956; chairman and CEO (chief executive officer) of JPMorgan Chase

since 2006) indeed did raise the matter with the chancellor although opinions

might differ on whether what he said could be classed as “mildly threatening”. In his

memoir, Alistair Darling (1953–2023; UK Chancellor of the Exchequer 2007-2010)

described a telephone call from Mr Dimon and recalled the banker was “very, very angry”

about the plan, arguing “..his bank bought a lot of UK debt and he wondered if that

was now such a good idea. I pointed out

that they bought our debt because it was a good business deal for them. He went on to say they were thinking of

building a new office in London, but they had to reconsider that now.” The lobbying didn’t change the chancellor’s

mind and the bonus tax was imposed as planned.

Mandy can’t be blamed for that; he did his bit.

Lindsay Lohan and her lawyer in court, Los Angeles, December, 2011.

Probably

the most amusing of Mandy’s reactions to the revelations about his past related

to payments he received from Epstein in 2003-2004 (US$75,000 to Mandy and Stg£10,000

to his partner Reinaldo Avila da Silva (the couple married in 2023)). When late in January, 2026 he resigned from

the Labour Party (it’s believed he’d been “tapped on the shoulder” and told he’d

be expelled if no letter of resignation promptly was received), he used the

usual line adopted these circumstances, saying he wished to spare the party “further embarrassment” and added: “Allegations which

I believe to be false that he made financial payments to me 20 years ago, and

of which I have no record or recollection, need investigating by me.” Few seemed to find plausible a man who has such

a history of “money grubbing” could fail to recall US$75,000 suddenly being

added to his bank balance and, unfortunately for Mandy, various authorities

have decided the matters “need investigating by them”.

In happier times: Mandy (left) with Sir Keir Starmer (right).

One who

seems to be taking the betrayals personally is Sir Keir Starmer (b 1962;

prime-minister of the UK since 2024) who appointed Mandy as the UK’s ambassador

to the US, the prime minister making clear his outrage at the lies Mandy (more

than once) told him and his staff during the (clearly inadequate) vetting

process. In one of his more truculent

speeches, Sir Keir contrasting himself with Mandy, pointing out that while he’d

come late to politics and entered the nasty business with the intention of trying

to improve the country, he contrasted that high aim with the long career of

Mandy who, it had become clear, viewed “climbing

the greasy” pole of public office as a device for personal enrichment. Hell hath no fury like a prime minister lied

to. Mandy has already resigned his seat

in the Lords (now something separate from his possession of the life peerage

conferred by Gordon Brown) although, all things considered, that probably was

one of history’s less necessary letters.

However, as well as referring his allegedly nefarious conduct to the

police and other investigative bodies, the government is said to be drafting

legislation to eject Mandy from the Lords and strip him of his noble title: Lord

Mandelson. Given that over the past century

odd members of the Lords have been jailed for conduct such as murder, perjury

and what was in the statute of 1553 during the reign of Henry VIII (1491–1547;

King of England (and Ireland after 1541) 1509-1547) called “the detestable and abominable vice of

buggery” yet not been stripped of their titles, the act will be a bit of a

novelty but constitutional experts agree it’s within the competence of

parliament, needing only the concurrence of both houses. Not since the passage

of the Titles Deprivation Act (1917)

have peerages been stripped and that statutory removal happened in the unusual

circumstances of World War I (1914-1918) when it was thought the notion of

Germans and Austrians holding British titles of nobility was not appropriate though

it was a measure of the way the establishment resists change that the war had

been raging three years before the act finally received royal assent.

The irony

of a gay man becoming entangled in the scandals surrounding a convicted child

sex trafficker who allegedly supplied men with girls younger than the age of consent has been noted,

some dwelling on that with unseemly relish; it was with both enthusiasm and and obvious relief that members of the Labour Party felt finally free to tell journalists (or anyone else who asked) just what they really thought of Mandy, their previously repressed views views tending to a thumbnail sketch which could be précised as: “evil and manipulative”. More generally, although it was the English common law which did so much to establish the principle of “innocent until proven guilty”, in parliament and beyond, the

consensus seems already reached that Mandy is “guilty as sin”; it’s a question of to

what extent and what’s to be done about it. That will play out but what may happen sooner is that Sir Keir could be the latest of the many victims of Mandy's machinations over the decades. For matters unrelated to Mandy, the prime minister had anyway been having a rugged time in the polls and on the floor of the house and all that that has thus far ensured the survival of his leadership is thought to be (1) the lack of an obvious contender in the Labour Party and (2) the ineptitude of the Tory opposition, the talents of its MPs now thought to be as low as at any time in living memory. Sadly, when discussing the travails of Sir Keir, it notable how many commentators have described him with terms like "decent", "integrity" and "honorable" (not qualities much associated with Mandy) but it remains unclear if the prime minister's commendable virtues will prove enough for his leadership to survive in the clatter of one of the moral panics the English do so well. Over the thirty-odd years, quite often the Labour Party apparatchiks have

had to ponder: “What are we going to do

about Mandy?” but this time it’s serious and there will be much effort devoted

to combining “damage limitation”

with what the baying mob will judge at least adequately condign.