Gate

(pronunced geyt)

(1) A movable barrier, usually on hinges, closing

an opening in a fence, wall, or other enclosure.

(2) An opening permitting passage through an

enclosure.

(3) A tower, architectural setting, etc., for

defending or adorning such an opening or for providing a monumental entrance to

a street, park etc.

(4) Any means of access or entrance.

(5) A mountain pass.

(6) Any movable barrier, as at a tollbooth or a

road or railroad crossing.

(7) A sliding barrier for regulating the passage

of water, steam, or the like, as in a dam or pipe; valve.

(8) In skiing, an obstacle in a slalom race,

consisting of two upright poles anchored in the snow a certain distance apart.

(9) The total number of persons who pay for

admission to an athletic contest, a performance, an exhibition or the total revenue

from such admissions.

(10) In cell biology, a temporary channel in a

cell membrane through which substances diffuse into or out of a cell; in flow

cytometry, a line separating particle type-clusters on two-dimensional dot

plots.

(11) A sash or frame for a saw or gang of saws.

(12) In metallurgy, (1) a channel or opening in a

mold through which molten metal is poured into the mold cavity (also called

ingate) or (2), the waste metal left in such a channel after hardening; (written

also as geat and git).

(13) In electronics, a signal that makes an

electronic circuit operative or inoperative either for a certain time interval

or until another signal is received, also called logic gate; a circuit with one

output that is activated only by certain combinations of two or more inputs.

(14) In historic British university use, to

punish by confining to the college grounds (largely archaic).

(15) In Scots and northern English use, a

habitual manner or way of acting (largely archaic).

(16) A path (largely archaic but endures in

historic references).

(17) As a suffix (-gate), a combining form

extracted from Watergate, occurring as the final element in journalistic

coinages, usually nonce words, that name scandals resulting from concealed

crime or other alleged improprieties in government or business.

(18) In cricket, the gap between a batsman's bat

and pad, used usually as “bowled through the gate”.

(19) In computing and electronics, a logical

pathway made up of switches which turn on or off; the controlling terminal of a

field effect transistor (FET).

(20) In airport or seaport design, a (usually numerically

differentiated) passageway or assembly point with a physical door or gate

through which passengers embark or disembark.

(21) In a lock tumbler, the opening for the stump

of the bolt to pass through or into.

(22) In pre-digital cinematography, a mechanism,

in a film camera and projector, that holds each frame momentarily stationary

behind the aperture.

(23) A tally mark consisting of four vertical

bars crossed by a diagonal, representing a count of five.

Pre 900:

From the Middle English gate, gat,

ȝate & ȝeat, from the Old English gæt, gat & ġeat

(a gate, door), from the Proto-Germanic gatą

(hole, opening). It was cognate

with the Low German and Dutch gat

(hole or breach), the Low German Gatt,

gat & Gööt, the Old Norse gata (path) and was related to the Old

High German gazza (road,

street). Yate was a dialectical form which was an alternative spelling until

the seventeenth century; the plural is gates. Many European languages picked up variations of

the Old Norse to describe both paths and what is now understood as a gate. The Old English geat (plural geatu) was

used to mean "gate, door, opening, passage, hinged framework

barrier", as was Proto-Germanic gatan,

and the Dutch gat; in Modern German,

it emerged as gasse meaning “street”;

the Finnish katu, and the Lettish gatua (street) are Germanic

loan-words. Interestingly, scholars

trace the ultimate source as the Primitive European ǵed (to defecate).

The meaning "money from selling tickets" dates from

1896, a contraction of 1820’s gate-money.

The first reference to uninvited gate-crashers is from 1927 and gated

community appears in 1989; that was Emerald Bay, Laguna Beach, California

although conceptually similar defensive structures had for millennia been built

in many places.

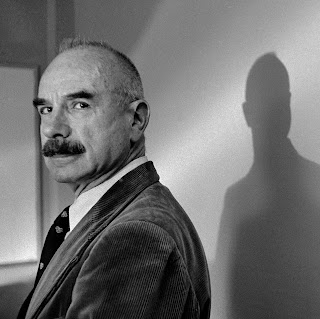

G Gordon Liddy (1930–2021) was the CREEP lawyer

convicted of conspiracy, burglary, and illegal wiretapping for his role in the

Watergate Affair. Receiving a

twenty-year sentence, he served over four, paroled after Jimmy Carter (b 1924; US President 1977-1981)

commuted the term to eight years. He was

one of the great characters of the affair.

The practice of using -gate as a suffix

appended to a word to indicate a "scandal involving," is a use abstracted from

Watergate, the building complex in Washington DC, which, in 1972, housed the national headquarters

of the Democratic Party. On 17 June, it was burgled by operatives found later to be associated with Richard Nixon's (1913-1994; US president 1969-1974) Campaign to Re-elect the President committee (CREEP). Since

Watergate, there have been at least dozens of –gates.

Notable Post-Watergate Gates

Billygate: In 1980, US President Jimmy Carter's

brother, Billy (1937-1988), was found to have represented the Libyan government as a

foreign agent. Cynics noted that, unlike

his brother, Billy at least had a foreign policy. Crooked Hillary Clinton (b 1947; US secretary of state 2009-2013) has provided the lexicon many "-gates".

A marvelous linguistic coincidence gave us Whitewatergate, a confusing package of real estate deals later found technically to be lawful and Futuregate was a reference to some still inexplicable (and profitable) dabbles in her

name in the futures markets. Servergate was the mail server affair which featured mutually

contradictory defenses to various allegations, the Benghazi affair and more. There was also a

minor matter but one which remains emblematic of character. Crooked Hillary Clinton, after years of fudging, was forced to admit she “misspoke” when claiming that to avoid sniper-fire, she and her entourage “…just ran with our heads down to get into the vehicles to get to our base” when landing at a Bosnian airport in 1996. She admitted she “misspoke” only after a video was released of her walking down the airplane’s stairs to be greeted by a little girl who presented her with a bouquet of flowers. Even her admission was constructed with weasel words: “…if I misspoke, that was just a misstatement”. That seemed to clear things up and the matter is now recorded in the long history of crooked Hillary Clinton's untruthfulness as Snipergate. Most bizarre was Pizzagate, a conspiracy theory that circulated during the 2016 US presidential campaign, sparked by WikiLeaks publishing a tranche of emails from within the Democrat Party machine. According to some, encoded in the text of the emails was a series of messages between highly-placed members of the party who were involved in a pedophile ring, even detailing crooked Hillary Clinton’s part in the ritualistic sexual abuse of children in the basement of a certain pizzeria in Washington DC. Among the Hillarygates, pizzagate was unusual in that she was innocent of every allegation made; not even the pizzeria's basement existed.

Closetgate: References the controversy following the 2005 South Park episode "Trapped in the Closet", a parody of the Church of Scientology in which the Scientologist film star Tom Cruise (b 1962) refuses to come out of a closet. Not discouraged by the threat of writs, South Park later featured an episode in which the actor worked in a confectionery factory packing fudge.

Grangegate: In Australia in 2014, while giving

evidence to the state's Independent Commission against Corruption (ICAC), Barry O'Farrell (b 1959; Premier of New South Wales 2011-2014) forget he’d been given

a Aus$3,000 bottle of Penfolds Grange (which he drank without disclosing the gift as the rules required). He felt compelled to resign.

Perhaps counterintuitively, there seems

never to have been a Lindsaygate or Lohangate.

In that sense, Lindsay Lohan may be said to have lived a scandal-free

life.

Irangate: Sometimes called contragate, this was

the big scandal of Ronald Reagan's (1911-2004; US president 1981-1989) second term. As a back channel operation, the administration had sold weapons to the Islamic Republic of Iran

and diverted the profits to fund the Contra rebels opposing the Sandinista

government of Nicaragua. Congress had earlier cut the funding.

Nipplegate: Sometimes called boobgate, this was a

reaction to singer Janet Jackson’s (b 1966) description of what happened at the

conclusion of her 2004 Superbowl performance as a “wardrobe malfunction”. In Europe, they just didn't get what all the fuss was about.

Monicagate: The most celebrated scandal of President Bill Clinton’s (b 1946; US President 1993-2001) second term. Named after White House intern Monica Lewinsky (b 1973), with whom the

president “…did not have sexual relations…”.

1973 Pontiac Trans-Am SD-455.Dieselgate: In 2015, Volkswagen was caught

cheating on emissions tests used to certify for sale some eleven-million VW diesel vehicles by

programming them to enable emissions controls during testing, but not during

real-world driving. Manufacturers had

been known to do this. In 1973 Pontiac

tried to certify their SD-455 (Super Duty) engine with a not dissimilar trick but the EPA (Environmental Protection Authority) wasn't fooled which is why the production SD-455 was rated at 290 HP (horsepower) rather

than 310. Later, manufacturers in the Fourth Reich turned out to be just as guilty and, in that handy phrase from German historiography "they all knew". Including the fines thus far levied, legal fees and the costs associated with product recalls, the affair is estimated so far to have cost VW some US$27 billion but the full accounting won't be complete for some time. Other German manufacturers were also affected but Daimler (maker of Mercedes-Benz) avoided a penalty by snitching on the others.

In Australia, Utegate was a 2009 campaign run by opposition leader Malcolm Turnbull (b 1954; prime-minister of Australia 2015-2018) and his then (they're no longer on speaking terms) henchman, Eric Abetz (b 1958, Liberal Party senator for Tasmania, Australia 1994-2022), which accused Dr Kevin Rudd (b 1957; Australian prime-minister 2007-2010 & 2013) of

receiving a backhander from a car dealer, the matters in question revolving around an old and battered ute (pick-up).

Based on documents forged by Treasury official Godwin Grech (b 1967), it led to

the (first) downfall of Turnbull. Abetz

went on to bigger things but Turnbull neither forgot nor forgave, sacking Abetz

during his second coming (which started well but ended badly). Abetz however proved he still has the numbers which matter, gaining preselection and in 2024 winning a seat in the Tasmanian Legislative Assembly (the state's lower house). He now serves as minister for business, industry & resources and minister for transport as well as leader of the house in the minority Liberal Party government.

The first Nutellagate arose at Columbia

University early in 2013 with allegations of organized, large-scale theft by

students of the Nutella provided in the dining halls. Apparently students,

unable to resist the temptation of the newly available nutty spread, were (1)

consuming vast quantities, (2) pilfering it using containers secreted in

back-packs and (3) actually purloining entire jars from the tables.

In the spirit of the investigative journalism

which ultimately brought down Richard Nixon, the Columbia Daily Spectator, breaking the story, reported that based on a leak from their deep throat in the

catering department, the crime was costing some US$5,000 per week, the hungry

students said ravenously to be munching their way through around 100 pounds (37 or 45 KG

(deep throat not specific whether the losses were weighed on the avoirdupois or

troy scale)) of Nutella every seven days.

The newspaper noted the heist was on such a scale that, unless addressed,

the cost to the university would be US$250,000 a year, enough to buy seven jars

for every undergraduate student.

The national media picked up the story noting, apart from the criminality, there were concerns about the relationship between the wastage of

food, excessively expensive student services, the exorbitant cost of tuition

fees and a rampant consumer culture. It

seemed a minor moral panic might ensue until the student newspaper (now a blog)

deconstructed the Spectator’s numbers

and worked out the caterers must be paying 70% more for Nutella than that quoted

by local wholesalers, casting some doubt on the matter. The university authorities

responded within days, issuing a press release headed “Nutellagate Exposed: It's

a Smear!" Their audit revealed that

the accounting system had booked US$2,500 against Nutella purchases in the

first week of term but that was the usual practice when stocking inventory and

that consumption was around the budgeted US$450 in subsequent weeks. Deep throat (Nutella edition) lost face and was discredited.

Nutellagate II broke in 2017 when a consumer

protection organization released a report noting the recipe had, without

warning, been changed, the spread now having more sugar and milk powder but

less cocoa and, as a result, was now of a lighter hue. Ferrero’s crisis-management operative responded

on twitter, tweeting “our recipe underwent a fine-tuning and continues to

deliver the Nutella fans know and love with high quality ingredients,”… adding “…sugar,

like other ingredients, can be enjoyed in moderation as part of a balanced

diet.”

#Nutellagate soon trended and users expressed displeasure,

many invoking the memory of New Coke or the IBM PS/2, two other products which appeared

also to try to fix something not broken.

The twitterstorm soon subsided, the speculation being that, because it

contained more sugar, consumers would become more addicted and soon forget the fuss. So it proved, sales remaining strong. Nutella though remains controversial because

of the sugar content and the use of palm oil, a product harvested from vast monocultural plantations and associated with social and environmental

damage. Ferrero has now and again

suggested they may be ceasing production but the user base has proved resistant

although, recent movements in the hazelnut price may test the elasticity of

demand.

Open-Gate Ferraris

The much admired but now almost extinct open-gate shifters were originally purely functional before becoming fetishized. At a time when more primitive transmissions and shifter assemblies were built with linkages and cables which operated with much less precision than would come later, the open-gates served as a guidance mechanism, making the throws more uniform and ensuring the correct movement of the controlling lever. Improvements in design actually made open-gates redundant decades ago but they'd become so associated with cars such as Ferraris and Lamborghinis that they'd become part of the expectations of many buyers and it wasn't hard to persuade the engineers to persist, even though the things had descended to be matters purely of style. A gimmick they may have become but, cut from stainless steel and often secured with exposed screw-heads, they were among the coolest of nostalgia pieces.

Reality eventually bit when modern, fast electronics meant automatic transmissions both shifted faster and were programmed always to change ratios at the optimal point and no driver however skilled could match that combination. Once essential to quick, clear shifts, by the late 1990s, the open-gate had actually become a hindrance to the process and while there were a few who still relished the clicky, tactile experience, such folk were slowly dying off and with sales in rapid decline, manufacturers became increasingly unwilling to indulge them with what had become a low-volume, unprofitable option.

Not all the Ferraris with manual gearboxes used the open-gate fitting, some of the grand-touring cars using concealing leather boots but both are now relics, the factory recently retiring the manual gearbox because of a lack of demand. The 599 GTB Fiorano was made between 2006-2012 and included the option but of the 3200-odd made, only 30 buyers specified the manual. That run of 30 was however mass-production compared with the California (2009-2014) which was both the first Ferrari equipped with a dual-clutch transmission and the last to offer a manual, ending the tradition of open gate-shifters which stretched back 65 years. Testing the market, a six-speed manual option had been added to the hard-top convertible in 2010 and the market spoke, the factory dropping it from the order sheet in 2012 after selling just three cars in three years. The rarity has however created collectables; on the rare occasions an open gate 599 or California is offered at auction, they attract quite a premium and there's now an after-market converting Ferraris to open gate manuals. It's said to cost up to US$40,000 depending on the model and, predictably, the most highly regarded are those converted using "verified factory parts".

2012 Ferrari California (top) and 2012 Cadillac CTS-V sedan.

So the last decade at Maranello has been automatic (technically “automated manual transmission”) all the way and although a consequence of the quest for ultimate performance, it wasn’t anything dictatorial and had customer demand existed at a sustainable level, the factory would have continued to supply manual transmissions. There is however an alternative, Cadillac since 2004 offering some models with manual transmission for the first time since the 1953 Series 75 (among the Cadillac crowd the Cimarron (1982-1988) is never spoken of except in the phrase "the unpleasantness of 1982" ) and by 2013, while one could buy a Cadillac with a clutch pedal, one could not buy such a Ferrari. For most of the second half of the twentieth century, few would have thought that anything but improbable or unthinkable.

Ferrari open-gate shifter porn

1965 250 LM

1967 330 GTC

1968 275 GTS/4 NART Spyder

1969 365 GTC

1972 365 GTB/4

1988 Testarossa

1991 Mondial-T Cabriolet

1994 348 Spider

2011 599 GTB Fiorano

2012 California