Macropterous (pronounced muh-krop-ter-uhs)

(1) In zoology (mostly in ornithology, ichthyology & entomology),

having long or large wings or fins.

(2) In engineering, architecture and design, a structure

with large, untypical or obvious “wings” or “fins”.

Late 1700s: The construct was macro- + -pterous. Macro is a word-forming element meaning “long, abnormally large, on

a large scale”, from the French, from the Medieval Latin, from the Ancient Greek μακρός (makrós),

a combining form of makrós (long) (cognate

with the Latin macer (lean; meager)),

from the primitive Indo-European root mak

(long, thin). In English it is used as a

general purpose prefix meaning “big; large version of”). The English borrowing from French appears as

early as the sixteenth century but it tended to be restricted to science until

the early 1930s when there was an upsurge in the publication of material on economics

during the Great Depression (ie as “macroeconomy” and its derivatives). It subsequently became a combining form

meaning large, long, great, excessive etc, used in the formation of compound

words, contrasting with those prefixed with micro-. In computing, it covers a wide vista but

describes mostly relatively short sets of instructions used within programs,

often as a time-saving device for the handling of repetitive tasks, one of the

few senses in which macro (although originally a clipping in 1959 of “macroinstruction”)

has become a stand-alone word rather than a contraction. Other examples of use include

macrophotography (photography of objects at or larger than actual size without

the use of a magnifying lens (1863)), macrospore (in botany, "a spore of

large size compared with others (1859)), macroeconomics (pertaining to the

economy as a whole (1938), macrobiotic (a type of diet (1961)), macroscopic

(visible to the naked eye (1841)), macropaedia (the part of an encyclopaedia

Britannica where entries appear as full essays (1974)) and macrophage (in

pathology "type of large white blood cell with the power to devour foreign

debris in the body or other cells or organisms" (1890)).

The

–pterous suffix was from the Ancient Greek, the construct being πτερ(όν) (pter(ón)

(feather; wing), from the primitive Indo-European péthr̥ (feather)

and related to πέτομαι (pétomai) (I

fly) (and (ultimately), the English feather) + -ous. In

zoology (and later, by extension, in engineering and design), it was appended

to words from taxonomy to mean (1) having wings and (2) having

large wings. Later, it was used also of

fins. The –ous suffix was from the Middle English -ous, from the Old French –ous

& -eux, from the Latin -ōsus (full, full of); a doublet of -ose in an unstressed position. It was used to form adjectives from nouns to

denote (1) possession of (2) presence of a quality in any degree, commonly in

abundance or (3) relation

or pertinence to. In

chemistry, it has a specific technical application, used in the nomenclature to

name chemical compounds in which a specified chemical element has a lower

oxidation number than in the equivalent compound whose name ends in the suffix

-ic. For example, sulphuric acid (H2SO4)

has more oxygen atoms per molecule than sulphurous acid (H2SO3). The comparative is more

macropterous and the superlative most macropterous. Macropterous & macropteran are adjectives

and macropter & macroptery are nouns; the noun plural is macropters.

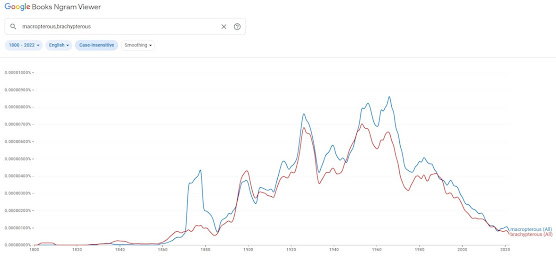

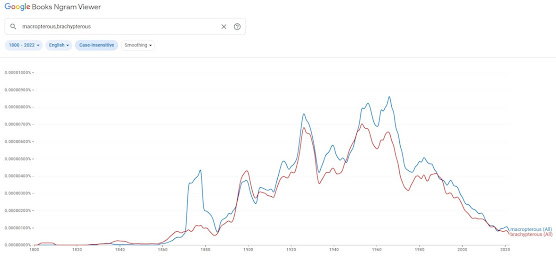

Google ngram: Because of the way Google harvests data for their ngrams, they’re not literally a tracking of the use of a word in society but can be usefully indicative of certain trends, (although one is never quite sure which trend(s)), especially over decades. As a record of actual aggregate use, ngrams are not wholly reliable because: (1) the sub-set of texts Google uses is slanted towards the scientific & academic and (2) the technical limitations imposed by the use of OCR (optical character recognition) when handling older texts of sometime dubious legibility (a process AI should improve). Where numbers bounce around, this may reflect either: (1) peaks and troughs in use for some reason or (2) some quirk in the data harvested.

Brachypterous (pronounced bruh-kip-ter-uhs)

In zoology (mostly in ornithology & entomology), having

short, incompletely developed or otherwise abbreviated

wings (defined historically as being structures which, when fully folded, do

not reach to the base of the tail.long or large wings or fins.

Late 1700s: The construct was brachy- + -pterous. The brachy-

prefix was from the Ancient Greek βραχύς (brakhús)

(short), from the Proto-Hellenic brəkús, from the primitive Indo-European mréǵus (short,

brief). The cognates

included the Sanskrit मुहुर् (múhur)

& मुहु (múhu), the Avestan m̨ərəzu.jīti (short-lived),

the Latin brevis, the Old English miriġe (linked ultimately to the English

“merry”) and the Albanian murriz. It was appended to convey (1) short, brief

and (2) short, small. Brachypterous & brachypteran are adjectives and brachyptery

& braˈchypterism are nouns. The comparative would be more

brachypterous and the superlative most brachypterous but because of the nature

of the base word, that would seem unnatural.

The noun brachypter does not means “a brachypterous creature; it

describes taeniopterygid stonefly of the genus Brachyptera”.

The European Chinch Bug which exists in both macropterous (left) and brachypterous (right) form; Of the latter, entomologists also use the term "micropterous" and use does seem interchangeable but within the profession there may be fine distinctions.

The difference in the use of macropterous (long wings or

fins) and brachypterous (short wings) is accounted for less by the etymological

roots than the application and traditions of use. In zoological science, macropterous was granted

a broad remit and came to be used of any creature (form the fossil record as

well as the living) with long wings (use most prevalent of insects) and

water-dwellers with elongated fins. The

word was applied first to birds & insects before being used of fish (fins

being metaphorical “wings” and in environmentally-specific function there is

much overlap. By extension, in the

mid-twentieth century, macropterous came to be used in engineering,

architecture and design including of cars, airframes and missiles.

Brachypterous (short wings) is used almost

exclusively in zoology, particularly entomology, the phenomenon being much more

common than among birds which, being heavier, rely for lift on wings with a

large surface area. Short wing birds do

exist but many are flightless (the penguin a classic example where the wings

are used in the water as fins (for both propulsion and direction)) and this

descriptor prevails. Brachypterous is less

flexible in meaning because tightly it is tied to a specific biological

phenomenon; essentially a “short fin” in a fish is understood as “a fin”. Cultural and linguistic norms may also have

been an influence in that while “macro-” is widely used a prefix denoting “large;

big”, “brachy-” has never entered general used and remains a tool in biology. So, in common scientific use, there’s no recognized

term specifically for “short fins” equivalent to brachypterous (short wings)

although, other than tradition, there seems no reason why brachypterous couldn’t

be used thus in engineering & design.

If so minded, the ichthyologists could coin “brachyichthyous” (the

construct being brachy- + ichthys (fish)) or brachypinnate (the construct being

brachy- + pinna (“fin” or “feather”

in Latin)), both meaning “short-finned fish”.

Neither seem likely to cath on however, the profession probably happy

with “short-fin” or the nerdier “fin hypoplasia”.

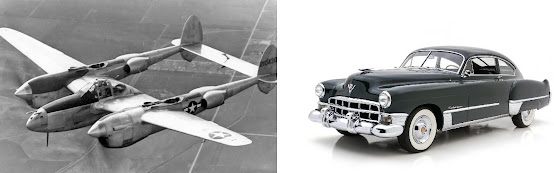

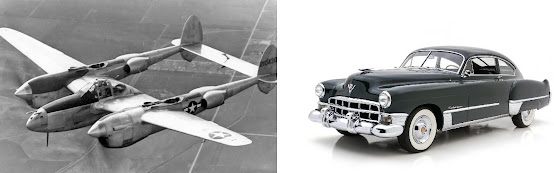

The tailfin: the macropterous and the brachypterous

Lockheed P-38 Lightning in flight (left) and 1949 Cadillac (right).

Fins had appeared on cars during the inter-war years when

genuinely they were added to assist in straight-line stability, a need

identified as speeds rose. The spread to

the roads came from the beaches and salt flats where special vehicles were

built to pursue the world land speed record (LSR) and by the mid 1920s, speeds

in these contests were exceeding 150 mph (240 km/h) and at these velocities,

straight-line stability could be a matter of life and death. The LSR crew drew their inspiration from

aviation and that field also provided the motif for Detroit’s early post-war

fins, the 1949 Cadillac borrowing its tail features from the Lockheed P-38

Lightning (a US twin-boom fighter first flown in 1939 and built 1941-1945)

although, despite the obvious resemblance, the conical additions to the front

bumper bar were intended to evoke the image of speeding artillery shells rather

than the P-38’s twin propeller bosses.

1962 Ford (England) Zodiac Mark III (left) and 1957 DeSoto Firesweep two-door hardtop (right). Chrysler in 1957 really did claim the tail-fins were not mere decorations but "stabilizers" designed to move the centre of pressure rearward.

From there, the fins grew although it wasn’t until in

1956 when Chrysler released the next season’s rage that extravagance truly began. To one extent or another, all Chrysler’s

divisions (Plymouth, Dodge, DeSoto, Chrysler, Imperial) adopted the macropterous

look and the public responded to what was being described in the press as “futuristic”

or “jet-age” (Sputnik had yet to orbit the earth; “space-age” would soon come)

with a spike in the corporation’s sales and profits. The competition took note and it wasn’t long

before General Motors (GM) responded (by 1957 some Cadillac fins were already there) although, curiously Ford in the US was

always tentative about the fin and their interpretation was always rather brachypterous

(unlike their English subsidiary which added surprisingly prominent fins to

their Mark III Zephyr & Zodiac (1961-1966).

Macropterous: Lindsay Lohan with wings, generated with AI (artificial intelligence) by Stable Diffusion. Even at the time the fins attracted criticism although it

was just as part of a critique of the newer cars as becoming too big and heavy

with a notable level of inefficiency (increasing fuel consumption and little

(if any) increase in usable passenger space with most of the bulk consumed by

the exterior dimensions, some created by apparently pointless styling features

of which the big fins were but one. The

public continued to buy the big cars (one did get a lot of metal for the money)

but there was also a boom in the sales of both imported cars (their smaller

size among their many charms) but the corporation which later became AMC

(American Motor Corporation) enjoyed good business for their generally smaller

offerings. Chrysler and GM ignored Ford’s

lack of commitment to the macropterous and during the late 1950s their fin continued

to grow upwards (and, in some cases, even outwards) but, noting the flood of

imports, decided to join the trend, introducing smaller ranges; whereas in

1955, the majors offered a single basic design, by 1970 there would be locally

manufactured “small cars”, sub-compacts”, “compacts” and “intermediates” as

well as what the 1955 (which mostly had been sized somewhere between a “compact”

and an “intermediate”) evolved into (now named “full-size”, a well-deserved appellation).

1959 Cadillac with four-window hardtop coachwork (the body-style known also as the "flattop" or "flying wing roof") (left) and 1961 Imperial Crown Convertible (right).

It was in 1959-1961 that things became “most macropterous”

(peak fin) and the high-water mark of the excess to considered by most to be

the 1959 Cadillac, east of the towering fins adorned with a pair of taillights

often described as “bullet lights” but, interviewed year later, a member of the

General Motors Technical Center (opened in 1956 and one of the mid-century’s

great engines of planned obsolescence) claimed the image they had in mind was

the glowing exhaust from a rocket in ascent, then often seen in popular culture

including film, television and advertising.

However, although a stylistic high, it was the 1961 Imperials which set

the mark literally, the tip of those fins standing almost a half inch (12 mm)

taller and it was remembered too for the “neo-classical” touch of four

free-standing headlights, something others in the industry declined to follow.

Tending to the brachypterous: As the seasons went by, the Cadillac's fins would retreat but would not for decades wholly vanish.

It’s a orthodoxy in the history of design that the fins

grew to the point of absurdity and then vanished but that’s not what literally happened

in all cases. Some manufacturers indeed

suddenly abandon the motif but Cadillac, perhaps conscious of having nurtured

(and in a sense “perfected”) the debut of the 1949 range must have felt more

attached because, after 1959, year after year, the fins would become smaller

and smaller although decades later, vestigial fins were still obviously part of

the language of design. In Europe,

others would also prune.

Macropterous to brachypterous. Sunbeam Alpine: 1960 Series I (left) and 1966 Series V.

Built in five series

between 1959-1968, the fins on the Sunbeam Alpine would have seemed a good idea

in 1957 when the lines were approved but trend didn’t persist and with the

release in 1964 of the revised Series IV, the effect was toned down, the

restyling achieved in an economical way by squaring off the rake at the rear,

this lowering the height of the tips.

Because the release of the Series IV coincided with the debut of the

Alpine Tiger (fitted initially with a 260 cubic inch (4.2 litre) V8 (and later

a 4.7 (289)), all the V8 powered cars used the “low fin” body.

Macropterous to brachypterous. 1961 Mercedes-Benz 300 SE Lang (Long) (left) and 1971 Mercedes-Benz 280 SE 3.5 coupé.

Regarded by some as a symbol

of the way the Wirtschaftswunder (the

post war “economic miracle” in the FRG (Federal Republic of Germany, the old

West Germany)) had ushered away austerity, the (slight) exuberance of the fins

which appeared on the Mercedes-Benz W111 (1959-1968) & W112 (1961–1965)

seemed almost to embarrass the company, offended by the suggestion they would

indulge in a mere “styling trend”.

Although the public soon dubbed the cars the Heckflosse (literally “tail-fins”), the factory insisted they were Peilstege (parking aids or sight-lines

(literally "bearing bars")), the construct being peil-, from peilen (take

a bearing; find the direction) + Steg

(bar) which marked the extent of the bodywork, this to assist while reversing. That may have been true (the company has

never been above a bit of myth-making) but when a coupé and cabriolet was added

to the W111 & W112 range, the fins were noticeably smaller, achieving an

elegance of line Mercedes-Benz has never matched. Interestingly, a la Cadillac, when the

succeeding sedans (W108-W109 (1965-1972) & W116, (1972-1979)) were released,

both retained a small hint of a fin although by 1972 it wasn’t enough even to

be called vestigial; the factory said the small deviation from the flat was

there to increase structural rigidity.

Macropterous to brachypterous: 1962 Vanden Plas Princess 3 Litre (left) and 1967 Vanden Plas Princess 4 Litre R (right).

The Italian design house

Pinninfarina took to fins in the late 1950s and applied what really were

variations of the same basic design to commissions from Fiat, Lancia, Peugeot

and BMC (British Motor Corporation, a conglomerate created by merger in 1952

which brought together Morris, Austin (and soon Austin-Healey), MG, Riley, Wolseley

& Vanden Plas under the one corporate umbrella. There were a several BMC “Farinas” sold under

six badges and the ones with the most prominent fins were the “big” Farinas,

the most expensive of which were Princess 3 Litre (1959-1960), Vanden Plas Princess

3 Litre (1960-1964) and Vanden Plas Princess 4 Litre R (1964-1968); the “R”

appended to the 4 Litre’s model name was to indicate its engine (which had

begun life as a military unit) was supplied by Rolls-Royce, a most unusual

arrangement. The 4 Litre used the 3

Litre’s body with a number of changes, one of which was a change in the shape

and reduction in the size of the rather chunky fins. Although the frumpy shell remained, the restyling was thought quite accomplished

though obviously influenced by the Mercedes-Benz W111 & W112 coupés &

cabriolets but if one is going to imitate, one should choose to emulate the finest.

1957 Herter

Duofoil Flying Fish Deluxe (15′ 7″ (4.75 m)).

Herter's outdoor goods business was

founded by George Herter (1911–1994) of Waseca, Minnesota. Mr Herter was a World War II (1939-1945)

combat veteran and it seems that while not exactly reclusive, he avoided

personal publicity although in addition to his manufacturing concerns and other

business interests, he was also a prolific author, his best remembered the Bull Cook Series (1960-1970) and Authentic Historical Recipes and Practices

(in three volumes) copies of which still circulate among collectors. He built his outdoor goods business (hunting,

fishing & shooting) using the mechanism of the mail-order catalog, long a

tradition in American commerce and the Amazon of the pre-internet age. The quality of the products offered was

apparently good but the imaginative Mr Herter labelled most of the items as “world famous”,

“model perfect”,

“state of the

art” and such while claiming many were endorsed by the (non-existent)

“North Star Guides Association”. Competition,

changes in patterns of consumption and the restrictions imposed by the Gun

Control Act (1968) (The second-hand Italian Carcano 6.5 mm rifle with which Lee

Harvey Oswald (1939–1963) shot John Kennedy (JFK, 1917–1963; US president

1961-1963) was purchased by mail-order (US$19.95 + US$1.50 P&H (postage

& handling)) made business difficult and Herter declared bankruptcy in 1977

although the trading-name was taken over by Cabela's and Bass Pro Shops which

still uses the brand.

The Herter

craft picked up the fin motif from GM & Chrysler but used only boating

industry standard red marker lights (left) rather than something like the

DeSoto triple-stack they perhaps deserved but one owner of a 1960 Herter Mark

III Flying Fish Runabout (14' (4.2 m), right) saw the potential and replaced

the modest lens with pair of the "twin bullet" items made famous on

the 1959 Cadillac. Unfortunately, they

weren't installed mid-fin which would have replicated the original

extravagance.

Mr Herter’s

early boats were for duck hunting and fishing but, noting the post-war boom in recreational

boating, the company expanded into the runabout market and the designs

reflected his fascination with GRP (glass-reinforced plastic and soon better

known as fibreglass) which he would use for a wide array of products,

continuing even after from withdrawing from the boat business. The first runabout was the “Chrome Fiberglass Duofoil World Famous

Deluxe Flying Fish” (one of Mr Herter’s typically bombastic names) and it

featured large, cast aluminum fins bolted to the rear deck. Although powerboats built for racing and

attempts on the WSR (water speed record) had long used fins to improve straight-line

stability, those on the Herter runabouts were about as related to aerodynamics

as Chrysler’s claim those on the 1957 Plymouths were “stabilizers”. Herter fins didn’t get smaller for 1957 but

were integrated with the fibreglass hull and in subsequent seasons became more

obviously streamlined. Apparently (and

reputedly intentionally) never a profitable line, Mr Herter in 1962 abandoned

the runabouts and focused production on the more utilitarian (and lucrative)

duck boats and rowboats.