Colonnade (pronounced kol-uh-neyd)

(1) In architecture, a series of regularly spaced columns

supporting an entablature and often one side of a roof.

(2) In design (usually as "colonnaded"), any array of upright structures which emulate the style of architectural colonnades.

(3) A series of trees planted in a long row, as on each

side of a driveway or road.

(4) The descriptor for the body style used in

the US on the General Motors (GM) “A-Body” platform 1973-1977.

1718: From the French colonnade,

from the Italian colonnato, from colonna (column), from the Latin columna (pillar), a collateral form of columen (top, summit), from the

primitive Indo-European root kel- (to

be prominent; hill). The related term is

colonnette which in architecture is a small slender column, sometimes merely decorative

but also structural, supporting a beam or lintel). In interior decorating and

furniture design, colonettes are also used, featuring in objects as diverse as

chairs, tables and mantle-clocks, the motif noted by archeologists in excavations

from Antiquity. The –ette

suffix was from the Middle English -ette,

a borrowing from the Old French -ette,

from the Latin -itta, the feminine

form of -ittus. It was used to form nouns meaning a smaller

form of something. Colonnade is a noun and colonnaded is an adjective; the

noun plural is colannades.

Colonnades at Piazza San Pietro, leading to St Peter's Basilica, Vatican City.

The noun peristyle described "a range or ranges of

columns surrounding any part or place".

It dates from the 1610s and was from the mid sixteenth century French péristyle (row of columns surrounding a

building), from the Classical Latin peristȳlum & peristȳlium, from the Ancient Greek περιστῡ́λιον (peristū́lion)

& περίστυλον (perístulon), a noun

use of the neuter form of περίστυλος (perístulos)

(surrounded by columns), the construct being περί (perí) + στῦλος (stûlos) (pillar), from the primitive Indo-European root sta- (to stand, make or be firm). In voodoo, it has the special meaning of “a

sacred roofed courtyard with a central pillar (the potomitan), used to conduct ceremonies, either alone or as an

adjunct to an enclosed temple or altar-room.

1974 Buick Century Luxus Colonnade Sedan

Under the traditional naming system used by General Motors

(GM), the code "A-body" was use for the intermediate platform, a body-on-frame

design in which the driveline and suspension were pre-assembled on a perimeter-frame

chassis to which the body subsequently was attached. The 1973-1977 GM A-Body cars were thus

structurally similar to the highly regarded 1964-1972 models but the body style

was radically different for a number of reasons, including some imposed by

legislation. One feature eliminated from the A-Body after 1973 was the hardtop, a body-style which used

frameless side-windows and no central (B) pillar. The much admired hardtop style had to be

sacrificed (though the fameless-windows were carried-over) because the new federal

legislation demanded improved roll-over protection, thus the need for B-pillars

to form a kind of integral roll-cage. This

was the era when safety and anti-pollution regulation first became stringent

and the 1973-1977 cars would be the first with the 5 mph (8 km/h) crash

bumpers, most early versions of which looked something like battering rams.

1973 Oldsmobile Colonnade Cutlass. In the 1970s, the Cutlass would become the best-selling car in the US but it's the previous generation A-Bodies (1964-1972) which are much sought.

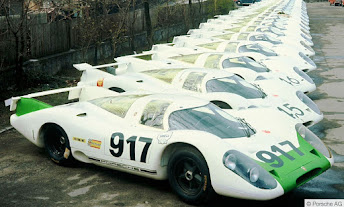

General Motors dubbed the style “Colonnade”, an allusion

to the array of three pillars where once there had been but two. Built at the time in big numbers with

production (spread between the Chevrolet, Buick, Oldsmobile & Pontiac

divisions) exceeding seven million, the survival rate was low compared with

their more illustrious (though sometimes lethally unsafe) predecessors and because few attained “collectable” status, no industry of replacement and re-production

parts emerged to make restorations conveniently possible. While the Colonnade cars don’t mark the dawn

of the “malaise era” for which the Carter administration is remembered

(although in the “Crisis of Confidence” speech which is taken as its marker,

Jimmy Carter (b 1924, US president 1977-1981) never spoke the word “malaise”),

the hints are certainly there that worse was to come.

1977 Pontiac Can Am advertising was apparently the only time Pontiac officially used the popular "GOAT" (greatest of all time) allusion to the GTO.

One (not especially bright) highlight of the Colonnade years

came almost at the end when Pontiac released the Can Am. By 1977, Pontiac was no longer making genuinely

fast or exciting cars (and in fairness, nor were many others) but with machines

like the Firebird Trans-Am, they were certainly making stuff which looked the

part and it was this flair for keeping-up-appearances which inspired the Can Am. One model which had disappointed the Pontiac hierarchy was the LeMans which, even by Colonnade standards was an unhappy looking

thing, the sloping rear end and buff-front apparently the work of two different

and not especially gifted committees. Fundamentally,

it couldn’t be fixed but the Detroit’s marketing people had worked before with

unpromising material and knew all about “tarting-up”.

1977 Pontiac Can Am.

The first proposal added a ducktail spoiler to the rear

which quite effectively disguised the drooping lines and revived the “Judge” name, a muscle-car

moniker from Pontiac’s recent past, added stripes and finished the thing in a lurid

red which was close to the Judge’s signature shade. Officially, the Pontiac management were said

to be “unenthusiastic” but apparently they were appalled and knew something so

obviously fake would not be well-received.

There the project might have died but the marketing team had a second

go, adding the Firebird Trans Am’s 400 cubic inch (6.6 litre) V8, keeping the

spoiler and changing the color to stark white, complemented with red, yellow

and orange stripes, the Swiss-Guardesque combination looking better than it sounds. The interior gained additional appointments,

borrowed from the Grand Prix, one Pontiac which was selling well and the name came

from a famous racing series which in its halcyon years had been contested by

the FIA’s Group 7, unlimited displacement sports cars. The Pontiac was a long way removed from that

but at the time, so was just about everything and the project was duly approved

for a mid-season (early 1977) introduction.

The spoiler which broke the mold: The 1977 Pontiac Can Am’s rear styling reflected GM’s thoughts on styling at the time, the same motifs appearing on the HJ-HX-HZ Holden sedans (1974-1980).

Sales began in January and the critical response was polite, the performance noted as being about as good as could be expected at the time and the handling receiving the usual praise, one improvement of the Colonnade era which was real. In a sign of the times, only an automatic transmission was offered and, in deference to California’s more exacting anti-pollution rules, Can Ams sold there were fitted with the less powerful Oldsmobile 403 cubic inch (6.6 litre) V8 also used in high-altitude regions. Sales projections were initially a modest 2500 units but the public clearly liked the look, dealers reporting high demand so the production schedule was doubled and the first batch of just over a 1000 cars was shipped. Unfortunately, it was at this point the hand-crafted mold used to form the ducktail spoiler broke and such had been the rush to market than there was no spare. Had the distinctive molding not been such a prominent part of the Can Am’s marketing materials, perhaps it might have been possible to proceed spoiler-less but it was decided to cancel the programme. Whether or not it’s an industry myth, the story has always been that because the Can Am depended on so many parts (especially the interior) from the parts bin of the fast-selling (and highly profitable) Grand Prix, Pontiac decided they’d rather have more of them. Total Can Am production was apparently 1377 units and they’re now regarded with more fondness than much of the machinery from the malaise era, the rarity and flamboyance of the Colonnade lines gaining them a small but seemingly secure niche in the collector market.

Lindsay Lohan in Falling for Christmas (Netflix, 2022). Any structure, small or large which adopts the architectural language of the colonnade (an array of vertical pillar-like structures) is said to be colonnaded. These are doors with colonnaded windows.