Rook (pronounced rook)

(1) A large

Eurasian passerine bird, Corvus

frugilegus, with a black plumage and a whitish base to its bill from the family

Corvidae (crows) and noted for its

gregarious habits.

(2) In slang, a swindler, someone who cheats at cards, dice etc; a

(3) In slang, someone who betrays (now rare).

(4) In slang, a bad deal; rip off.

(5) In historic English slang, a parson, vicar, priest etc (based on the traditional black cassock clerics wore). A variant with a similar origin was Adolf Hitler's (1889-1945; Führer (leader) and German head of government 1933-1945 & head of state 1934-1945) disparaging German Roman Catholic clergymen as “diese schwarzen Krähen” (those black crows).

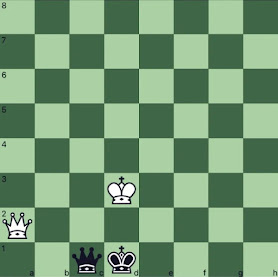

(6) In chess, one of four pieces (two of each color) that may be moved any number of unobstructed squares horizontally or vertically; also called castle. Rooks start the game on the four corners of the board.

(7) As chess rook, in

Canadian heraldry, the cadency mark of a fifth daughter.

(8) In cards, a trick-taking game, played usually with a specialized deck.

(9) As rookie, a type of firecracker used by farmers in the UK to scare birds (including, but not restricted to, rooks).

(10) To cheat, fleece or swindle.

Pre 900: From the Middle English rok & roke, from the Old English hrōc, from the Proto-West Germanic hrōk, from the Proto-Germanic hrōkaz. In other languages there was the Old Norse hrókr, the Saterland Frisian Rouk, the Middle Swedish roka, the Old High German hruoh (crow), the Middle Dutch roec and Dutch roek (and the obsolete German Ruch, from the primitive Indo-European kerk- (crow, raven). Related avian forms included the Old Irish cerc (hen), the Old Prussian kerko (loon, diver), the dialectal Bulgarian кро́кон (krókon) (raven), the Ancient Greek κόραξ (kórax) (crow), the Old Armenian ագռաւ (agṙaw), the Avestan kahrkatat (rooster), the Sanskrit कृकर (kṛkara) and the Ukrainian крук (kruk) (raven). The Old French was roc, from the Spanish rocho & ruc, from the Arabic رُخّ (ruḵḵ), from the Persian رخ (rox). Use as the bird’s name was possibly imitative of its raucous voice, an etymology hinted at by other languages (the Gaelic roc (as in "croak") and the Sanskrit kruc (as in "to cry out")). Rook & rooking are nouns & verbs, rookery, rooker & rooklet are nouns, rooked is a verb, rookish, rooless, rooklike & rooky are adjectives, rookie is a noun, verb & adjective and rookwise is an adjective & adverb; the noun plural is rooks.

Chess pieces.

Rook was applied as a disparaging term for persons since at least the early sixteenth century, extended by the 1570s to mean "a cheat", especially at cards or dice, this probably associated with the thieving habits of the rook, a habit it shares with other acquisitive corvine birds like the crow and magpie. The adverb rookwise can be applied to anyone or anything said to be moving exclusively in “a cardinal direction” (ie toward any of the four principal points of the compass: north, south, east and west), as a rook moves on a chessboard. In use, it’s applied usually to mean “in the perpendicular or horizontal” (as opposed to a curve, diagonal or other angle) though not of necessity to true north, south, east or west. The companion term is bishopwise (moving exclusively in diagonals, as a bishop moves on a chessboard). A rooker is a person who cheats or swindles but the victim is not described as a “rookee”; other terms are applied to these unfortunates. Rookie means (1) someone new to some activity (much used thus in sport), (2) an inexperienced recruit (much used thus in the military & law enforcement) and (3) a firecracker used in the UK to scare birds away from crops) but it’s only the use in agriculture which is related to the bird. Rookie may have been some sort of phonetic derivative for “recruit” or may be from either (1) the Dutch broekie (short for broekvent (a boy still so young as to be in short trousers)) which was a common a common term for “a shipmate” or (2) the Irish rúca (an inexperienced person).

Chess arrived in Russia perhaps as early as the ninth century, the path via the Islamic world from India and soon it was being played in much of Europe. The rook gained its name from the chaturanga, the piece used in Indian chess and represented by a रथ (ratha) (a war chariot); when the game was adopted by the Persians, ratha became رخ (rukh) (chariot), the term retained by the Arabic-speaking world and in this form it reached Europe. It was adapted in the Italian as rocco and in the Old French as roc or roche, the later influencing English when eventually it evolved into rook (although in Middle English the name of the chess piece was sometimes confused with the roc (the enormous mythical bird in Eastern legend). The name thus changed little between languages and nor did the strategic role of the piece vary: chariot-like fast, powerful charges in straight lines.

The use of “castle” as the informal name for the rook was an unintended consequence of the operation of phonetic similarity in the sub-set of the population practicing an oral culture. Apparently in southern Italy, some rural folk interpreted rukh as the Italian rocca (fortress or rock) and this led to a new visual representation: the rook as a castle tower or siege tower, the position in the corner of the board reflecting its defensive strength. This quickly became the standard shape in European chess pieces and historians of the game have speculated that because carving a plausible “castle turret” from a small base of wood, stone or metal would have been quicker and easier (and this cheaper) than a “chariot”, the economics of production may also have been persuasive. It was European folk etymology that created “castle” as the alternative and it has survived to become (depending on one’s view), informal, incorrect or old-fashioned and has been cited as a class-identifier (a la Knave vs Jack in playing cards): In Noblesse Oblige: An Enquiry Into the Identifiable Characteristics of the English Aristocracy (1956) Nancy Mitford (1904–1973) didn’t list the chess pieces but had she bothered the rook would have been the “U” word and castle the “non-U”. Curiously, even among those who insist the piece is a rook, use persists in the move “castling” in which the rook and king can switch positions along the “base-line” (ie rows 1 & 8). Chess purists insist this is the only permissible use of “castle” but seem resigned to the “mistake’s” regrettable survival.