Mania (pronounced mey-nee-uh

or meyn-yuh)

(1) Excessive excitement or enthusiasm; craze; excessive

or unreasonable desire; insane passion affecting one or many people; fanaticism.

(2) In psychiatry, the condition manic disorder; a

combining form of mania (megalomania); extended to mean “enthusiasm, often of

an extreme and transient nature,” for that specified by the initial element; characterized

by great excitement and occasionally violent behavior; violent derangement of

mind; madness; insanity.

(3) In mythology, the consort of Mantus, Etruscan god of

the dead and ruler of the underworld. Perhaps

identified with the tenebrous Mater Larum, she should not be confused with the

Greek Maniae, goddess of the dead; In Greek mythology Mania was the

personification of insanity.

(4) In popular use, any behavior, practice, cultural phenomenon,

product etc enjoying a sudden popularity.

1350–1400: From the Middle English mania (madness), from the Latin mania

(insanity, madness), from the Ancient Greek μανία (manía) (madness, frenzy; enthusiasm, inspired frenzy; mad passion,

fury), from μαίνομαι (maínomai) (I am

mad) + -ῐ́ᾱ (-íā). The –ia suffix was from the

Latin -ia and the Ancient Greek -ία

(-ía) & -εια (-eia), which form abstract nouns of

feminine gender. It was used when names

of countries, diseases, species etc and occasionally collections of stuff. The Ancient Greek mainesthai (to rage, go mad), mantis (seer) and menos (passion, spirit), were all of uncertain origin but probably

related to the primitive Indo-European mnyo-,

a suffixed form of the root men- (to

think)," with derivatives referring to qualities and states of maenad (mind) or thought.

The

suffix –mania was from the Latin mania,

from the Ancient Greek μανία (mania)

(madness). In modern use in psychiatry

it is used to describe a state of abnormally elevated or irritable mood,

arousal, and/or energy levels and as a suffix appended as required. In general use, under the influence of the

historic meaning (violent derangement of mind; madness; insanity), it’s applied

to describe any “excessive or unreasonable desire; a passion or fanaticism”

which can us used even of unthreatening behaviors such as “a mania for flower

arranging, crochet etc”. As a suffix,

it’s often appended with the interfix -o- make pronunciation more natural. The sense of a "fad, craze, enthusiasm resembling

mania, eager or uncontrollable desire" dates from the 1680s, the use in

English in this sense borrowed from the French manie. In Middle English,

mania had sometimes been nativized as manye.

The familiar modern use as the second element in compounds expressing

particular types of madness emerged in the 1500s (bibliomania 1734, nymphomania,

1775; kleptomania, 1830; narcomania 1887, megalomania, 1890), the origin of

this being Medical Latin, in imitation of the Greek, which had a few such

compounds (although, despite the common perception, most were actually post-classical:

gynaikomania (women), hippomania

(horses) etc).

The adjective maniac was from circa 1600 in the sense of "affected

with mania, raving with madness" and was from the fourteenth century French

maniaque, from the Late Latin maniacus, from the Ancient Greek maniakos, the Adoption in English

another borrowing from French use; from 1727 it came also to mean "pertaining

to mania." The noun, "one who is affected with mania, a madman" was

noted from 1763, derived from the adjective.

The adjective manic (pertaining to or affected with mania), dates from 1902,

the same year the clinical term “manic depressive” appeared in the literature

although, perhaps strangely, the condition “manic depression” wasn’t describe

until the following year although the symptoms had as early as 1857 been noted

as defined as “circular insanity”, from the from French folie circulaire (1854). It’s

now known as bi-polar disorder. The

constructions hypermania & submania are both from the mid-twentieth

century. The adjective maniacal was from

the 1670s, firstly in the sense of "affected with mania" and by 1701

"pertaining to or characteristic of a maniac; the form maniacally emerged

during the same era. Mania is quite

specific but craving, craze, craziness, enthusiasm, fad, fascination, frenzy,

infatuation, lunacy, obsession, passion, rage, aberration, bee, bug,

compulsion, delirium, derangement, desire & disorder peacefully co-exist.

Noted manias

Anglomania: An excessive or undue enthusiasm for England

and all things English; rarely noted in the Quai D'Orsay.

Anthomania: An extravagant passion for flowers; although

it really can’t be proved, the most extreme of these are probably the orchid

fanciers. Those with an extravagant passion

for weed are a different sub-set of humanity and are really narcomanics (qv) although

there may be some overlap.

Apimania: A passionate obsession with bees; beekeepers tend

to be devoted to their little creatures so among the manias, this

one may more than most be a spectrum condition.

Arithmomania: A compulsive desire to count objects and

make calculations; noted since 1884, it’s now usually regarded as being within

the rubric of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

Bibliomania: A rage for collecting rare or unusual books. This has led to crime and there have been famous cases.

Cacodaemomania: The obsessive fixation on the idea that

one is inhabited by evil spirits. To the

point where it becomes troublesome it’s apparently rare but there are dramatic

cases in the literature, one of the most notorious being Anneliese Michel

(1952–1976) who was subject to the rites of exorcism by Roman Catholic priests

in the months before she died. The priests

and her parents (who after conventional medical interventions failed, also become convinced the cause of her problems was

demonic possession) were

convicted of various offences related to her death. Films based on the events leading up to death

have been released including The Exorcism

of Emily Rose (2005), Requiem

(2006) and Anneliese: The Exorcist Tapes

(2011).

Callomania: The obsessive belief in one’s own beauty,

even when to all others this is obviously delusional.

Dipsomania: The morbid craving for alcohol; in pre-modern

medicine, it was used also to describe the “temporary madness caused by excessive

drinking”, the origin of this being Italian (1829) and German (1830) medical

literature.

Egomania: An obsessive self-centeredness; it was known

since 1825 but use didn’t spike until Freud (and others) made it widely discussed after the 1890s and few terms from the early days of

psycho-analysis are better remembered.

Erotomania: Desperate love, a sentimentalism producing

morbid feelings.

Flagellomania: An obsessive interest in flogging and/or

being flogged, often as one’s single form of sexual expression and thus a

manifestation of monomania (qv). The

English Liberal Party politician Robert Bernays (1902-1945), the son of a

Church of England vicar, was a flagellomanic whose proclivities were, in the

manner of English society at the time, both much discussed and kept

secret. He was also an illustration of

the way such fetishes transcend other sexual categories.

Gallomania: An excessive or undue enthusiasm for France

and all things French; rarely noted in the British Foreign Office.

Graphomania: A morbid desire to write. Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527; Italian diplomat,

philosopher and political advisor of the Renaissance) attributed many of the

problems he suffered to his graphomania and he was right, his sufferings

because of what he wrote, when it was written and about whom.

Hippomania: An excessive fondness for horses; an

affliction which often manifests as the intense and passionate interest in horses

developed by some girls who join pony clubs and fall in love.

Hypermania: There’s a definitional dualism to hypermania;

it can mean either an extreme example of any mania or, as used by clinicians,

specifically (and characterized usually by a mental state with high intensity

disorientation and often violent behavior), a severe case of bipolar disorder

(the old manic-depression). The earlier

term was hypomania (A manic elation accompanied by quickened perception), one

of the earliest (1882) clinical terms from early-modern psychiatry.

Kleptomania: The obsessive desire to steal; in early

(1830s) use, the alternative form was cleptomania. The klepto

element was from the Ancient Greek kleptes

(thief, a cheater), from kleptein (to

steal, act secretly), from the primitive Indo-European klep- (to steal), from the root kel-

(to cover, conceal, save) and was cognate with the Latin clepere (to steal, listen secretly to), the Old Prussian au-klipts (hidden), the Old Church

Slavonic poklopu (cover, wrapping)

and the Gothic hlifan (to steal)

& hliftus (thief). The history of the word kleptomania is of

interest also to sociologists in that as early as the mid-nineteenth century,

there was controversy about the use by those with the capacity to buy the

services of doctors and lawyers were able to minimize or escape the

consequences of criminal misbehavior by claiming a psychological motive. The argument was that the “respectable”

classes were afforded the benefit of this defense while the working class were

presumed to be inherently criminal and judged accordingly. The same debate, now also along racial

divides, continues today.

Lindsaymania: A specific instance of mania suffered by those obsessed with Lindsay Lohan (manifested often on Instagram and other social media platforms), including those poor deluded souls who curate blogs with substantial Lohanic content. They are sometimes referred to as "Lindsaiacs". Those who focus on Ms Lohan's feet were historically labeled podophiles but the DSM has since re-classified them as "foot particularists"; if their interest is restricted to her feet alone they are a subset of the Lindsaymaniacs whereas if their interest includes the feet of others, they are pure foot particularists.

Logomania: An obsession with words. It differs from graphomania (qv) which is an

obsession to write; logomania instead is a fascination with words, their meanings and etymologies.

Megalomania: Delusions of greatness; a form of insanity

in which the subjects imagine themselves to be great, exalted, or powerful

personages. It was first used in the

medical literature in 1866 (from the French mégalomanie)

and came to be widely applied to many politicians and potentates the

twentieth century.

Micromania:

"A form of mania in which the patient thinks himself, or some part

of himself, to be reduced in size", noted first in 1879 and twenty years

later used also in reference to insane self-belittling. In the twentieth century and beyond,

micromania was widely used, sometimes humorously, to refer to things as varied

as the sudden consumer in interest in small cars to the shrinking size of

electronic components.

Monomania: An insane obsession in regard to a single

subject or class of subjects; applied most often in academic, scientific or

political matters but can be used about anything where the overriding mental

impulses are perverted to a specific delusion or the pursuit of a particular

thing.

Morphinomania: A craving for morphine; one of the

earliest of the words which noted specific addictions, it dates from 1885 but

earlier still there had been morphiomania (1876) and morphinism (1875) from the

German Morphiumsucht. In the medical literature, morphinomaniac

& morphiomaniac rapidly became common.

Narcomania: The uncontrollable craving for narcotic

drugs and a term which is so nineteenth century, the preferred modern form being variations of "addiction".

Necromania: An obsession to have sexual relations with

the bodies of the dead although, perhaps surprisingly, practitioners (those who

treat rather than practice the condition) classify many different behaviors

which they list under the rubric of necromania, some of the less confronting

being a morbid interest in funeral rituals,

morgues, autopsies, and cemeteries.

Those whose hobbies include the study of the architecture of crypts and

tombs or the coachwork of funeral hearses might be shocked to find there are psychiatrists who

classify them in the same chapters as those who enjoy intimacy with corpses.

Nymphomania: The morbid and uncontrollable sexual desire

in women. Perhaps the most celebrated

(and often sought) of the manias, it dates from 1775, in the English

translation of Nymphomania, or a Dissertation Concerning the Furor Uterinus

(1771) by French doctor Jean Baptiste Louis de Thesacq de Bienville (1726-1813),

the construct being the Ancient Greek nymphē

(bride, young wife; young lady) + mania.

The actual condition is presumed to have long pre-dated the term and in use, deserves to be distinguished from less pleasing modern forms such as the "skanky ho".

Onomatomania: One obsessively compelled to respond with a

rhyming word to the last word spoken by another (something possible even with orange and

silver). It’s thought to co-exist with

other conditions, especially schizophrenia.

Phonomania: An uncontrollable urge to murder; those who suffer this now usually described as the more accessible “homicidal maniac”. When applied especially to serial killers,

the companion condition (just further along the spectrum) is androphonomania

which, if properly argued, could be a defense against a charge of mass-murder

but counsel would need to be most assiduous in jury selection.

Plutomania: The obsessive pursuit of wealth (and used

sometimes in a clinical setting to describe an "imaginary possession of

wealth").

Pyromania: A form of insanity marked by a mania for

destroying things by fire. It was used

in German in the 1830s and seemed to have captured the imagination of Richard

Wagner (1813–1883); the older word for the condition was incendiarism.

Rhinotillexomania: Nose picking. Gross, but a thing which

apparently often manifests when young but fades, usually of its own volition or

in reaction to the disapprobation of others.

Trichotillomania: The compulsion to pull-out one’s

hair. The companion condition is trichtillophagia

which is the compulsive eating of one’s own hair, one of a remarkable number of

eating disorders.

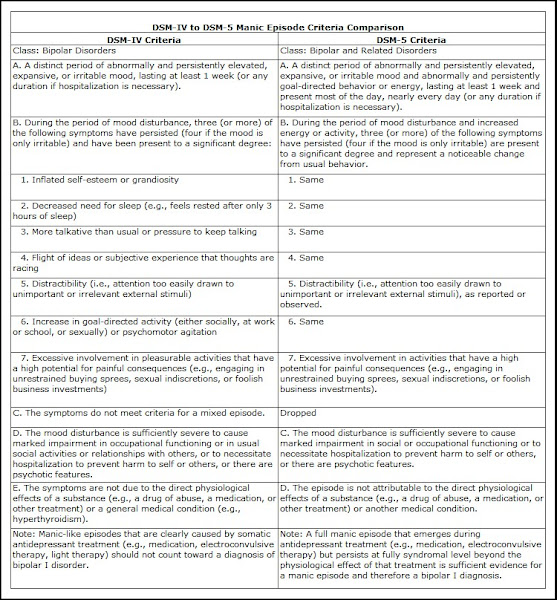

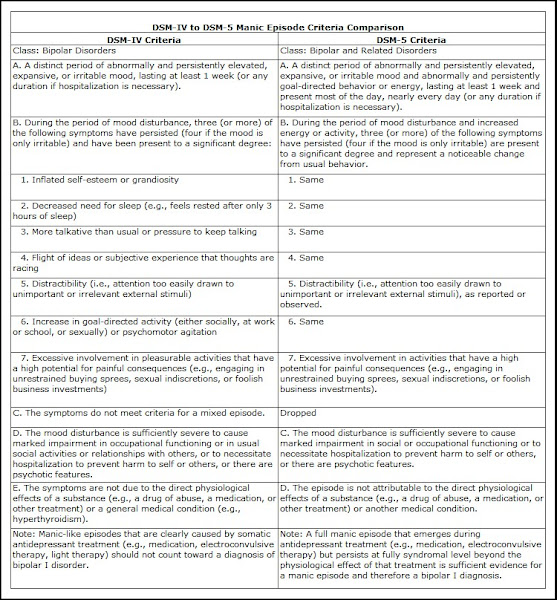

Definitional variations in the criteria for mania, DSM-IV

& DSM-5

The study and classification of idea of manias had been

part of psychiatry almost from its origin as a modern discipline although the

wealth of details and fragmentation of nomenclature would come later, the

condition first noted “increased busyness”, the manic episodes characterized by

Emil Kraepelin (1856-1926; a founding father of psychiatric phenomenology) as those

of someone who was “…a stranger to

fatigue, his activity goes on day and night; work becomes very easy to him;

ideas flow to him.”

Whatever the advances (and otherwise) in treatment regimes,

little has changed in some aspects of the condition. In the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders (DSM-5, 2013), the primary criterion of mania remains “a distinct period of abnormally and

persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood” and “abnormally and persistently increased

goal-directed activity or energy” but did extend duration of the event to

qualify for a diagnosis. In the DSM-IV

(1994), the criterion for a manic episode only required “a distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive,

or irritable mood, lasting at least one week” whereas DSM-5 now requires in

addition the presence of “abnormally and

persistently increased goal-directed activity or energy”; moreover, these

symptoms must not only last at least one week, they must also be “present most of the day, nearly every day.”

The changes certainly affected the practice of the clinician,

DSM-5 substantially increasing the complexity associated with the diagnosis and

treatment of bipolar disorder, no longer requiring that clinically significant

symptoms which may be present should be ignored. All those years ago, Kraepelin conceptualized

manic-depression as a single illness with a continuum of episodic presentations

including admixtures of symptoms which have long since been considered opposing

polarity. DSM-5 thus represents an

advance with the possibility of improved treatment outcomes because it enables

clinicians to diagnose mood episodes and specify the presence of symptoms

inconsistent with pure episodes; a major depressive episode with or without

mixed features and manic/hypomanic episodes with or without mixed features.

The revisions in DSM-5 also reflect the efforts of the editors

over several decades to simplify diagnostic criteria while developing more

precise categories of classification. In

the DSM-IV, both bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder were included in

one chapter of mood disorders and a “mixed state” was a subtype of bipolar I

mania, a diagnosis of a mixed state requiring that criteria for both a manic

episode (at least three or four of seven manic symptoms) and a depressive

episode (at least five of nine depressive symptoms) were met for at least one

week. In DSM-5, bipolar disorder and

depressive disorders have their own chapters, and “mixed state” was removed and replaced with “manic episode with

mixed features” and “major depressive

disorder with mixed features.”