Orthogonal (pronounced awr-thog-uh-nl)

(1) Of,

pertaining to or involving right angles;

perpendicular

(2) In mathematics (sometimes as orthographic), pertaining

to or involving right angles or perpendiculars.

(3) In mathematics, of a system of real functions defined

so that the integral of the product of any two different functions is zero; of

a system of complex functions defined so that the integral of the product of a

function times the complex conjugate of any other function equals zero.

(4) In mathematics, of two vectors having an inner

product equal to zero.

(5) In mathematics, of a linear transformation defined so

that the length of a vector under the transformation equals the length of the

original vector.

(6) In mathematics (and applied fields such as

engineering or statistics), of a square matrix defined so that its product with

its transpose results in the identity matrix.

(7) In crystallography, referable to a rectangular set of

axes.

(8) Figuratively, something having no bearing on the

matter at hand; independent of or irrelevant to another thing or each other.

(9) In art, (1) the descriptor of the lines of

perspective which can be mapped onto an image pointing to the vanishing point

& (2) in the literature of art criticism a technical term which refers to

work consisting exclusively of horizontal or vertical line and thus angles

which, if they exist, are right angles.

1565–1575: From (the now obsolete) orthogonium (right triangle), from the French orthogonal,

from either the Late Latin orthogōnium & orthogōnālis,

from the Latin orthogōnius (right-angled).or

directly from the Greek orthogṓnion (neuter) (right-angled),

the construct being ortho- + -gōn(ion)

+ -al. Ortho-

(straight, correct; proper), was from the Ancient Greek ὀρθός (orthós),

from the Proto-Hellenic ortwós, from the primitive Indo-European hr̥dwós, from herd- (upright) and was cognate with the Latin arduus and the Sanskrit ऊर्ध्व (ūrdhvá). The –gon

element was from the Ancient Greek γωνία (gōnía)

(corner, angle), from the primitive Indo-European ǵónu (knee). The -al suffix was from the Middle English -al, from the Latin adjectival suffix -ālis, or the French, Middle French and

Old French –el & -al.

It was use to denote the sense "of or pertaining to", an

adjectival suffix appended (most often to nouns) originally most frequently to

words of Latin origin, but since used variously and also was used to form

nouns, especially of verbal action. The

alternative form in English remains -ual

(-all being obsolete). Orthogonal is a noun & adjective,

orthogonality & orthogonalization are nouns and orthogonally & orthonormal

are adverbs; the noun plural is orthogonals.

As adjectives, orthogonal & orthographic are synonymously

and the choice is dictated by preference, habit or the rhythm of the text

although, to avoid confusion, they probably shouldn’t both be used in the same

document. The Ancient Greek ὀρθογώνιον (orthogṓnion) and the Classical Latin orthogonium originally denoted a

rectangle and it was in this sense the words were used by the early

mathematicians although the use was later extended to mean a right triangle. By the twelfth century (especially among

engineers and architects) the post-Classical Latin orthogonalis came to mean a right angle or something related to a

right angle. In the modern era, in science

and mathematics, derived forms have been coined as required (biorthogonal, pseudo-orthogonal

etc) and there’s also the mysterious semiorthogonal which would seem oxymoronic

given orthogonal is a description of a mathematically defined absolute. In figurative use, orthogonal is used to

suggest something is unrelated or irrelevant to whatever is being discussed but

because it’s so rarely used outside of mathematics, engineering, architecture

or art criticism, it’s probably a term to avoid though it may be worth a point

or two in Philosophy 101.

Lindsay Lohan in an unusual cage cutout top, the lines assuming or relaxing from the orthogonal as the body moves (maybe an instance of "a shifting semiorthogonal"). The combo was a Black Pash shirt with & Alaia skirt, The World's First Fabulous Fund Fair in aid of The Naked Heart Foundation, The Roundhouse, London, February 2015. The t-strap sandals were by Miu Miu) but an an opportunity was missed by not adding a sympathetic clutch purse.

Richard Nixon, the Franklins & the Orthogonians

When Richard Nixon (1913-1994; US president 1969-1974)

attended Whittier College in California (1930-1934), it was still formally affiliated

with the Religious Society of Friends (the Quakers), a link it would maintain

until the post-war years. However, in

many ways it was little different to wholly secular institutions in the US

(except that one hour a day in chapel was mandatory), including the fraternities

and sororities, the still almost exclusively single-sex, student-run societies which

were established on many a basis and have evolved variously although a number

of the male-only ones often attract attention related to their epic levels of

alcohol consumption. As was the case

with many colleges until recent decades, many of those which Richard Nixon

found when he arrived had been formed as literary societies and while there

were four sororities (for women), there was but one fraternity.

That was the Franklin Society which in 1921 had been the first

fraternity founded at Whittier College, beginning as a literary society that

based itself on the "virtues" espoused by US founding father and

polymath (and confessed Freemason) Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790). Nixon, then unpolished and obviously a

shop-keeper’s son, thought them snobby and elitist, an opinion either formed or

reinforced when the Franklins rebuffed attempts to join and readily he accepted

the suggestion be assume the presidency of the fraternity formed by other

students resentful at being rejected by the Franklins. This was the Orthogonians, the name (based on

the now standard translation “right angles”) meaning “the straight shooters”,

their motto an earthy “beans, brains, brawn and bowels”. The Orthogonians did not enjoy the black tie

lifestyle of the Franklins and weren’t invited to the best parties but several

of Nixon’s biographers have traced from his fraternity experience many of the

characteristics which would remain identifiable throughout this political

career. He learned that in life there

are few stars but many supporting players and the man who can align himself

with their interests can gain their loyalty, something of real practical

value in systems where everyone has one vote; it was the origin of his idea

that elections and contests of ideas can be won by being appealing to the “silent

majority”, something which would emerge as a political strategy during his

presidency. It taught him also that

being hated was no obstacle to political success as long as one was hated by

the right people, something he proved by beating the Franklin’s nominee for the

position of student body president. To

this day, the Frankin’s website still boasts: “Among those who have been denied membership to this exclusive society

is former president Richard Nixon.” The Orthogoian Society still exists.

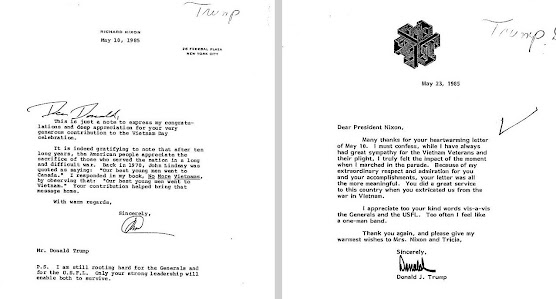

Some biographers have made much of the Franklin-Orthogonian contrast in the making of Nixon the younger. In Nixonland (2008), Rick Perlstein’s (b 1969) thesis was that between 1965-1972, Nixon crafted a national conflict by exploiting the the mutual fear and hatred between the country’s elite Franklins and the “ordinary people”, the Orthogonians. Some criticized the approach but Nixonland was a vivid approach to the era in which the divisions in the US became more exposed than they had been for a century and which was a prelude to the cross-cutting cleavages which have for decades characterized the country’s politics. Nixon didn’t invent the politics of resentment but he expressed them in a language more easily understood by even the unsophisticated and more offensive than ever to those he labeled “the elites”. In their own ways, to their radically different constituencies, Bernie Sanders (b 1941; senior US senator (Independent, Vermont) since 2007) and Donald Trump (b 1946; US president 2017-2021) are both inheritors of the Nixon legacy, two Franklins telling the Orthogonians they’re here to help.