Brat (pronounced brat)

(1) A child, especially one is

ill-mannered, unruly, annoying, spoiled or

impolite etc (usually used either playfully or in contempt or irritation, often

in the phrase “spoiled brat”.

(2) As “military brat”, “army brat” etc, a child with one

or more parent serving in the military; most associated with those moving

between military bases on a short-duration basis; the derived form is “diplomatic

brat” (child living with parents serving in overseas missions).

(3) In the BDSM (bondage/discipline,

dominance/submission, sadism/masochism) community, a submissive partner who is

disobedient and unruly (ie a role reversal: to act in a bratty manner as the

submissive, the comparative being “more bratty”, the superlative “most bratty”).

(4) In mining, a thin bed of coal mixed with pyrites or

carbonate of lime.

(5) A rough makeshift cloak or ragged garment (a now

rare dialectal form).

(6) An apron fashioned from a coarse cloth, used to

protect the clothing (a bib) (a now obsolete Scots dialect word).

(7) A turbot or flatfish.

(8) The young of an animal (obsolete).

(9) A clipping of bratwurst, from the German Bratwurst (a

type of sausage) noted since 1904, from the Middle High German brātwurst, from the Old High German, the

construct being Brāt (lean meat,

finely shredded calf or swine meat) + wurst

(sausage).

(10) As

a 2024 neologism (technically a

re-purposing), the qualities associated with a confident and assertive woman

(along the lines of the earlier “bolshie woman” or “tough broad” but with a

more overtly feminist flavor).

1500–1520: Thought to be a transferred use (as slang for “a

beggar's child”) of the early Middle English brat (cloak of coarse cloth, rag), from the Old English bratt (cloak) of Celtic origin and

related to the Old Irish brat (mantle,

cloak; cloth used to cover the body). The origin of the early Modern English slag

use meaning “beggar's child” is uncertain.

It may have been an allusion, either to the contemporary use meaning “young

of an animal” or to the shabby clothing such a child would have worn", the

alternative theory being some link with the Scots bratchet (bitch, hound). The

early sense development (of children) may have included the fork of the notion

of “an unplanned or unwanted baby” (as opposed to a “bastard” (in the technical

rather than behavioral sense)) had by a married couple. The “Hollywood Brat Pack” was a term from the

mid-1980s referring to a grouping of certain actors and modeled on the 1950s “Rat

Pack”. The slang form “brattery” (a

nursery for children) sounds TicTokish but actually dates from 1788 while the

generalized idea of “spoiled and juvenile” became common in the 1930s. The unrelated use of bratty (plural bratties)

is from Raj-era Indian English where it describes a cake of dried cow dung,

used for fuel. Brat is a noun, verb

& adjective, brattishness & brattiness are nouns, bratting &

bratted are verbs, brattish & bratty are adjectives and brattily is an

adverb; the noun plural is brats.

New York magazine, 10 June, 1985.

First

published in 1968, New York magazine is now owned by Vox media and, unlike

many, its print edition still appears on surviving news-stands. The editorial focus has over the decades

shifted, the most interesting trend-line being the extent to which it could be

said to be very much a “New York-centred” publication, something which comes

and goes but the most distinguishing characteristic has always been a

willingness (often an eagerness) to descend into pop-culture in a way the New

Yorker's editors would have distained; it was in a 1985 New York cover story

the term “Brat Pack” first appeared.

Coined by journalist David Blum (b 1955) and about a number of

successful early twenty-something film stars, the piece proved controversial

because the subjects raised concerns about what they claimed was Blum’s

unethical tactics in obtaining the material.

The term was a play on “Rat Pack” which in the 1950s had been used of an

earlier group of entertainers although Blum also noted another journalist's coining

of “Fat Pack”, used in restaurant-related stories.

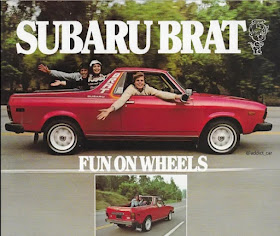

LBJ, the "Chicken Tax" and the Subaru BRAT

Subaru BRAT, advertising in motion (in a US publication and thus a left-hand drive model).

The Subaru BRAT was (depending on linguistic practice)

(1) a coupé utility, (2) a compact pick-up or (3) a small four wheel drive

(4WD) ute (utility). The name was an acronym

(Bi-drive Recreational All-terrain Transporter), the novel idea of “bi-drive” (4WD) being the notion of both axles being driven, that linguistic construction dictated by the need to form the acronym. “Bi-Drive Recreational All-Terrain

Transporter” certainly was more imaginative (if opportunistic) than other uses

of BRAT as an acronym which have included: ”Behaviour

Research And Therapy” (an academic journal), “Bananas, Rice, Applesauce and Toast” (historically a diet recommended

for those with certain stomach disorders), “Brush

Rapid Attack Truck” (a fire-fighting vehicle), “Basenji Rescue and Transport” (a dog rescue organization), “Behavioral Risk Assessment Tool” (used

in HIV/AIDS monitoring), Beautiful, Rich

and Talented (self-explanatory), the “Bureau de Recherche en Aménagement du

Territoire” (the Belgium Office of Research in Land Management (in the

French)), “Beyond Line-Of-Sight Reporting

and Tracking” (a US Army protocol for managing targets not in visual range)

and “Battle-Management Requirements

Analysis Tool” (a widely used military check-list, later interpolated into

a BMS (Battle Management System).

Ronald Reagan on his Santa Barbara ranch with Subaru BRAT. Like many owners who used their BRATs as pick-up trucks, President Reagan had the jump seats removed.

Built on the platform of the Leone (1971-1994) and known

in some markets also as the MV Pickup, Brumby & Shifter, the BRAT was

variously available between 1978-1994 and was never sold in the JDM (Japanese

domestic market) although many have been “reverse imported” from other places (Australia favored because salt isn't used on the roads so rust is less of an issue) and the things now have a cult following in Tokyo. The most famous BRAT owner was probably Ronald

Reagan (1911-2004; US president 1981-1989) who kept a 1978 model on his Californian

ranch until 1988, presenting something of a challenge for his Secret Service

detail, many of whom didn’t know how to drive a stick-shift (manual

transmission). That though would have

been less frightening than the experience of many taken for a drive by Lyndon

Johnson (LBJ, 1908–1973; US president 1963-1969) in the Amphicar 770 (1961-1965)

he kept at his Texas ranch. LBJ suddenly

would turn off the path, driving straight into the waters of the dam, having

neglected to tell his passengers of the 770’s amphibious capabilities. Although

“770” has been used in the industry (in the US and Australia) as a trim-level

designation (often as part of the sequence 440, 550, 660 etc) , on the amphibious Amphicar it was a reference to it being able to

achieve speeds of 7 knots (8 mph; 13 km/h) on water and 70 mph (110 km/h) on

land, both claims verified by testers although the nautical performance did

demand reasonable calm conditions.

The Subaru BRAT is remembered also as a “Chicken Tax car”. Tax regimes have a long history of

influencing or dictating automotive design, the Japanese system of displacement-based

taxation responsible for the entire market segment of “Kei cars” (a clipping of

kei-jidōsha (軽自動車) (light automobile), the

best known of which have been produced with 360, 600 & 660 cm3 (22, 37

& 40 cubic inch) engines in an astonishing range of configurations ranging

from micro city cars to roadsters and 4WD dump trucks. In Europe too, the post-war fiscal threshold resulted

in a wealth of manufacturers (Mercedes-Benz, Jaguar, BMW, Ford, Maserati, Opel

etc) offering several generations of 2.8 litre (171 cubic inch) sixes while

the that imposed by the Italian government saw special runs of certain 2.0 litre

(122 cubic inch) fours, sixes & even V8s.

The US government’s “Chicken Tax” (a part of the “Chicken War”) was

different in that it was a 25% tariff imposed in November 1963 (to come into effect in January 1964) by the Johnson administration

on potato starch, dextrin, brandy and light trucks; it was a response to the

impost of a similar tariffs by France and the FRG (Federal Republic of Germany,

the old West Germany) on chicken meat imported from the US.

Wheeling & dealing: Walter Reuther (left) and LBJ (right), scheming something, November 1963.

In any

president’s political horse trading there are always hidden agendas and

ulterior motives and in LBJ’s White House there were more than usual because

that’s the way he’d always done business and had he written a guide to the process, he might have called it "The Art of the Deal". He was in his generation the most skilled of all, historians concluding after

in 1937 having been initiated into the fraternity of Freemasons, he took the only

first degree (as an “Entered Apprentice”) and opted not further to progress

because soon he understood there was little even the Masons could teach him about

the dark arts of plotting & scheming.

Year after the imposition of the chicken tax, the contents of the

surviving tape-recordings of discussions in the White House revealed LBJ was negotiating

with UAW (United Auto Workers’) president Walter Reuther (1907–1970) in the

run-up to the 1964 congressional & presidential elections and the tariffs aimed

at curtailing Volkswagen’s increasing market share were just one of the “quid pro quo chips” on the table. Although it was the taping system used by Richard

Nixon (1913-1994; US president 1969-1974) that became infamous, devices of this

kind had been installed in the White House as early as the during the

administration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR, 1882–1945, US president

1933-1945) and Nixon actually had LBJ’s devices removed before his staff came

to understand their usefulness and Nixon agreed to having them re-fitted, the

rest being history.

Subaru BRAT in use.

The post-war development in the US of large scale, intensive

chicken farming had both vastly expanded production of the meat and radically

reduced the unit cost of production which was good but because supply quickly

exceeded the demand capacity of the domestic market, the surplus was exported,

having the effect in Europe of transforming chicken from a high-priced delicacy

to a staple consumer protein; by 1961, imported US chicken had taken some 50% of

the European market. This was at a time

when international trade operated under the General Agreement on Tariffs and

Trade (the GATT (1947)) and there was nothing like the codified dispute

resolution mechanism which exists in the rules of the successor World Trade

Organization (the WTO (1995)) and the farming lobbies in Germany, France and

the Netherlands accused the US producers of “dumping” (ie selling at below the

cost of production) with the French government objecting that the female hormones US

farmers used to stimulate growth were a risk to public health, not only to those who ate

the flesh but to all because nature of the substances was such that a residue enter the water supply. The use of the female hormones in agriculture

does remains a matter of concern, some researchers linking it to phenomena noted

in the last six decades including the startling reduction in the human male's sperm

count, the shrinking in size of the penises of alligators living in close

proximity to urban human habitation and early-onset puberty in girls.

Subaru BRAT Advertising (US).

Eventually, the tariffs on potato starch, dextrin and

brandy were lifted but the protection for the US truck producers remained,

triggering a range of inventive “work-arounds” concocted between various engineering

and legal offices, most of which involved turning two-seater trucks & vans

into vehicles which technically could quality as four-seaters, a configuration

which lasted sometimes only until the things reached a warehouse where the fittings could

be removed, something which would cost the Ford Motor Company (one of the corporations

the tax had been imposed to protect) over US$1 billion in penalties, their

tactics in importing the Transit Connect light truck from Turkey (now the

Republic of Türkiye) just too blatant.

In New Zealand, in the mid 1970s, the government found the “work-arounds”

working the other way. There, changes had

been implemented to make the purchase of two seater light vans more attractive

for businesses so almost instantly, up sprang a cottage industry of assembling

four-door station wagons with no rear seat which, upon sale, returned to the

workshop to have a seat fitted. Modern capitalism

has always been imaginative.

Subaru "Passing Lamp" on Leone 1600 GL station wagon (optional on BRATs, 1980-1982).

In Fuji Heavy Industries’ (then

Subaru’s parent corporation) Ebisu boardroom, the

challenge of what probably was described as the “Chicken Tax Incident” was met

by adding to the BRAT two plastic, rear-facing jump

seats, thereby qualifying the vehicle as a “passenger car” subject in the US only to a

2.5 and not a 25% import tax. Such a “feature”

probably seems strange in the regulatory environment of the 2020s but there was

a time when there was more freedom in the air.

Subaru’s US operation decided the BRAT’s “outdoor bucket seats” made it

an “open tourer” and slanted the advertising thus, the model enjoying much

success although the additional seating wasn’t available for its final season

in the US, the BRAT withdrawn after 1987.

Another nifty feature available on the BRAT between 1980-1982 was the “Passing

Lamp” (renamed “Center Lamp” in 1982 although owners liked “Third Eye” or “Cyclops”),

designed to suit those who had adopted the recommended European practice of

flashing the headlights (on high beam) for a second prior to overtaking. The BRAT was not all that powerful so passing

opportunities were perhaps not frequent but the “passing lamp” was there to be

used if ever something even slower was encountered. The retractable lamp was of course a complicated solution to a

simple problem given most folk so inclined just flash the headlights but it was

the sort of fitting with great appeal to men who admire intricacy for its own

sake.

BRAT seat mountings 1983 (left) and 1984 (centre). The BRAT on the right has been retro-fitted with the seats (note the safety wire attached to the frame!) using U-bolts, a satisfactory method provided (1) the U-bolts are of high-tensile steel and (2) there is a backing place of adequate strength and size.

The seats were bolted to a frame (the design of which changed) which was welded to the bed. The use of welding rather than bolts was dictated by the regulations because, had the frame been bolted (and thus defined as “removable”), the BRAT's classification would have changed from “passenger vehicle” to “truck” and been subject to the very tax the seats were installed to avoid. Amusingly though, the side impact regulations which applied to the BRAT were in a different act and for those purposes the thing was defined as a truck which meant the doors could be fitted with lighter reinforcing bars than those mandated for the Subaru Leone sedans, station wagons and hatchbacks. The stronger mechanism can be installed in a BRAT's doors so safety conscious owners do have that option.

Two 1987 BRATs with retro-fitted seats, the one on the right also with an after-market roll-bar, something which, all things considered, seems a sensible addition. Of the physics, those familiar Sir Isaac Newton's (1642–1727) First Law of Motion (known also as the Law of Inertia: "An object at rest will remain at rest, and an object in motion will continue in motion with the same speed and in the same direction unless acted upon by an unbalanced external force") can ponder the possibilities while wondering whether to bother buckling up the seat belt or just rely on the "grab handles" (and probably never was that term used more appropriately). Although the seats weren't factory-fitted after 1985, the parts could still be ordered and many later models have been retro-fitted. The adjustable headrests were a nice touch although some did note they could be classified also as "rear window protectors".

Brat: Charli XCX's Summer 2024 album

Charli XCX, BRIT Awards, O2 Arena, London, February 2016; the "BRITs" are the British Phonographic Industry's annual popular music awards.

“Brat” has been chosen by the Collins English Dictionary

as its 2024 Word of the Year (WotY), an acknowledgement of the popular acclaim

which greeted the word’s re-purposing by English singer-songwriter Charli XCX

(the stage-name of Charlotte Emma Aitchison (b 1992)) who used it as the title for her summer 2024

album. The star herself revealed her stage

name is pronounced chahr-lee ex-cee-ex; it has no connection with Roman numerals and XCX is anyway not a standard

Roman number. XC is “90” (C minus X

(100-10)) and CX is “110” (C plus X (100 +10)) but XCX presumably could be used

as a code for “100” should the need arise, on the model of something like the “May

35th” reference Chinese Internet users used in an attempt to circumvent the CCP's (Chinese Communist Party) "Great Firewall of China" when speaking of

the “Tiananmen Square Incident” of 4

June 1989. In 2015, Ms XCX revealed “XCX”

was an element of her MSN screen name (CharliXCX92) when young (it stood for “kiss Charli kiss”) and she used it on

some of the early promotion material for her music.

Charli XCX with Brat album (vinyl pressing edition) packaging in "brat green".

According to Collins, the word “resonated with people globally”. The dictionary had of course long had an

entry for the word something in the vein of: “someone, especially a child, who behaves

badly or annoys you”, but now it has added “characterized by a confident, independent,

and hedonistic attitude”. In

popular culture, the use spiked in the wake of the album's released but it may

be “brat” in this sense endures if the appeal is maintained, otherwise it will

become unfashionable and fade from use, becoming a “stranded word”, trapped in the

time of its historic origin. So, either

it enters the vernacular or by 2025 it will be regarded as “so 2024”. The lexicographers at Collins seem optimistic

about its future, saying in the WotY press release that “brat summer has established

itself as an aesthetic and a way of life”.

Lindsay Lohan in Jil Sander (b 1943) "brat green" gown, Disney Legends Awards ceremony, Anaheim, Los Angeles, October 2024. For anyone

wanting to describe a yellowish-green color with a word which

has the virtues of (1) being hard to pronounce, (2) harder to spell and (3) likely

to baffle most of one’s interlocutors, there’s “smaragdine” (pronounced smuh-rag-din), from the Latin smaragdinus, from smaragdus (emerald), from the Ancient Greek σμάραγδινος (smáragdinos), from σμάραγδος (smáragdos).

The “kryptonite green” used for Brat’s album’s packaging seems also to have encouraged the use in

fashion of various hues of “lurid green” (the particular shade used by Ms XCX

already dubbed “brat green” although some which have appeared on the catwalks seem more of a chartreuse) and an online “brat generator” allowed users

replicate the cover with their own choice of words. The singer was quite helpful in fleshing out

the parameters of the aesthetic, emphasizing it didn’t revolve around a goth-like

“uniform” and nor was it gender-specific or socially restricted. In an interview with the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation), Ms XCX explained

the brat thing was a spectrum condition extending from “luxury” to “trashy” and was a thing of

attitude rather than accessories: “A pack of cigs, a Bic lighter, and a strappy white top

with no bra. That’s kind of all you

need.” Although

gender-neutral, popular use does seem to put the re-purposed “brat” in the

tradition of the earlier “bolshie woman” or “tough broad” but with a more

overtly feminist flavor, best understood as “the qualities associated with a confident

and assertive woman”. In its semantic

change, “brat” has joined some other historically negative words & phrases

(“bitch”, “bogan”, the infamous “N-word(s)” etc) which have been “reclaimed” by

those at whom the slur was once aimed, a tactic which not only creates or

reinforces group identity but also re-weaponizes what was once a spent-insult so it

can be used to return fire.