Cokebottle (pronounced koke-bott-el)

A descriptor for a design where objects either resemble or

are inspired by the shape of the classic Coca-Cola bottle.

1965: From an unsuccessful trademark application file in the US by the Chevrolet division of General Motors (GM), cokebottle thus word that never was. The Coca-Cola name was a deliberately alliterative creation which referred to two of the original ingredients (leaves of the coca plant and kola nuts (source of the caffeine). Coca is from the Erythroxylaceae family of cultivated plants native to western South America and renowned as the source of the psychoactive alkaloid. Used since the drink’s debut in 1886, the cocaine was removed from Coca-Cola in 1903, the remainder of the recipe remaining famously secret. Coke dates from 1908 in US English and was a clipping of clipping of cocaine although it’s not known when the word was first used to refer to the drink but given the rapidity with which slang forms emerge to describe popular products, it’s at least possible it pre-dated the drug reference although the company did not lodge a trade-mark application for Coke until 1944 although in internal company documents it appears at least as early as 1941. While the drink produced a number of derived forms (Diet Coke, Coke-Bottle, frozen Coke, Coke-float, Coke Zero and the most unfortunate New Coke), those attached to the narcotic are more evocative and include coke dick, cokehead, coke whore and coke-fucked. Bottle was from the Middle English botel (bottle, flask, wineskin), from the Old French boteille (from which Modern French gained bouteille), from the Medieval Latin butticula, ultimately of uncertain origin but thought by most etymologists to be a diminutive of the Late Latin buttis (cask, barrel). Buttis was probably from a Greek form related to the Ancient Greek πυτίνη (putínē) (flask) and βοῦττις (boûttis), from the imitative primitive Indo-European bhehw (to swell, puff).

Lindsay Lohan seems to tend to prefer her Coca-Cola in cans but occasionally is seen drinking from the bottle.

Between its unpromising origin in 1926 as a lower-cost

alternative to the anyway non-premium Oakland brand and its demise (with a whimper)

in 2010, Pontiac in the 1960s did enjoy a brief, shining moment of innovation

and style. Pontiac had been one of a

number of companion brands introduced by GM as part of a

marketing plan to cover every price segment (the so-called "Sloan Ladder" conceived by Alfred P Sloan (1875–1966; president of General Motors (GM) 1923-1937 and Chairman of the Board 1937-1946)) with a distinct nameplate, Cadillac

gaining LaSalle, Oldsmobile gaining Viking, Oakland gaining Pontiac and Buick

gaining Marquette; only the high-volume Chevrolet stood alone. The idea was that as one's wealth increased, one would take the "next step on the ladder" so that after the ninth and final step, the man who once bought a Chevrolet now bought a Cadillac, after which there was nowhere else to go except another new Cadillac. The effects of the Great Depression meant the

experiment didn’t last and GM would soon to revert six divisions, the newcomers Viking

and Marquette axed while Pontiac, which had proved both more successful and

profitable than the shuttered Oakland, survived, joined LaSalle which lingered until

1940 and then there were five. Pontiac also returned to the line-up

when car production resumed late in 1945 and, benefiting from the buoyant

post-war economy, enjoyed success although much of the engineering was based on

that of Chevrolet while the side-valve engines were obsolescent. Things began to change in 1955 when a new

overhead-valve (OHV) V8 was introduced, a power-plant which faithfully would

serve the line for a quarter century in displacements between 265 cubic inches (4.3

litres) and 455 (7.5L) and, unusually for US manufacturers during the era,

Pontiac used the one basic block for all iterations. By 1955, all Pontiacs sold in the US were V8

powered (some sixes were still made for overseas markets) and the division

began to become more adventurous, joining the power race, fielding cars in

competition and moving up-market. However,

the first real master-stroke (one of several innovations which

would contribute to such stellar growth in both sales and reputation in the

decade to come) was the introduction in 1959 of the "wide-track" advertising

campaign.

1959 Pontiac convertibles: A Canadian Parisienne (left) built on the Chevrolet X-Frame and a US Catalina (right) on Pontiac’s wide-track frame; note the gaping wheel-wells on the Canadian car.

There were not a few visual exaggerations in the wide-track advertising

campaign but the underlying engineering was real, the track (the distance

between the centre of the tyre-tracks across each axle-line) increased by 5

inches (125 mm). This improved the

handling, giving the Pontiacs a more sure-footed stance than most of the competition

and an attractive low-slung look, If anyone had any doubts about the

veracity of the “wide track” claim, the Canadian Pontiacs were there for

comparison. Because of internal

corporate agreements, the bodies of the Canadian Pontiacs were mounted on the

Chevrolet X-frame with its narrow track and the difference is obvious, the wheels

looking lost inside the cavernous lacunas created by the overhanging

bodywork. In the US, sales soared and while a comparison with the recession-hit 1958 is probably misleading, the success of the wide-track programme did propel the division from sixth to

fourth place in the industry and for much of the 1960s Pontiac Motor Division (PMD) was one of the industry's most dynamic name-plates.

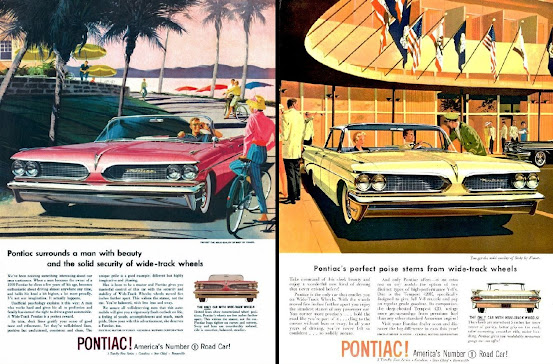

1960s Pontiac Wide-Track advertising graphic art by Art Fitzpatrick (1919–2015) & Van Kaufman (1918-1995).

Memorable as the 1960s Pontiacs were, of note too was the graphic art produced by Art Fitzpatrick (1919–2015) & Van Kaufman (1918-1995) whose renderings were ground-breaking in the industry in that rather than focusing on the machine, they were an evocation of an life-style, albeit one which often bore little relationship to those enjoyed by typical American consumers. Still, that was and remains the essence of aspirational advertising and Fitzpatrick & Kaufman influenced their industry with techniques still seen today and students of art history would identify elements from mannerism. The pair didn't take things so far they became surrealists but truth-in-advertising rules in the 1960s were not as demanding as they would become; although the big Pontiacs after 1959 genuinely were wide-tracked, they weren’t quite as wide as Fitzpatrick & Kaufman made them appear. Never had "longer, lower & wider" really been that wide.

Envious of what Pontiac had achieved in trade-marking wide-track for the wide track advertising campaigns, GM’s Chevrolet division attempted to claim both cokebottle and coke-bottle for similar purposes, wishing to run a campaign to tie in with their new styling idea for its big cars, using similar curves to those seen on the classic coke bottle. The authorities in Detroit declined the application and legal advice to Chevrolet suggested there was little chance of success against likely opposition from the Coca-Cola Corporation.

Chevrolet Impala two-door hardtops: 1965 (left), 1966 (centre) & 1967 (right).

However, along with much of the industry, Chevrolet did produce cars inspired by the shape which came to be known as coke bottle styling and on the big cars, the cokebottle motif was expressed mostly in the curves applied to the rear-coachwork. Chevrolet toned-down the look in 1968-1969 but by then it had spread to other manufacturers, including those across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and although by the early 1970s it was dated, the realities of production-line economics meant the look in some places lingered, even into the 1980s, the odd revival (usually in the rear-fender shape) still seen from time-to-time though modern interpretations do (except on sports cars and their ilk) tend to be more subtle than the exuberant lines of the 1960s. Essentially bodies with outward curving fenders with a narrow centre, the technique had also been adopted by the aeroplane designers as a necessary means of dealing with the aerodynamic challenges created by supersonic speeds and although the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) labelled the design principle area rule, most engineers referred to it as coke bottle or, among themselves, the Marilyn Monroe.

1969 Chevrolet Corvette L88 convertible. The classic example of cokebottle styling is the third generation (S3) Chevrolet Corvette (1968-1982) where the idea is executed front and rear. In the design of twenty-first century sports cars, the motif still appears.

Coca-Cola bottles and a replica of the 1914 A.L.F.A. Aerodinamica Prototipo (aerodynamic prototype) which used the shape of the bottle introduced in 1900). The replica is now exhibited at the Alfa Romeo Historical Museum in Arese.

In the narrow technical sense, cokebottle styling had been done as early as 1914 although there’s nothing to suggest Coca Cola's bottle design of 1900-1914 provided any inspiration. The A.L.F.A. 40/60 HP Aerodinamica Prototipo was built by Italian coachbuilder Carrozzeria Castagna in 1914 on a commission from Milanese Count Marco Ricotti (the distinctive machine at the time described as the Siluro Ricotti (the Ricotti Torpedo)). Although relatively large & heavy, the designers assumed the aerodynamic properties of the teardrop-shaped body (the coach-builder listed it as a "droplet", an instance of Italian borrowing from English) would permit the then impressive top speed of 150 km/h (93 mph), a useful increase of 25 km/h (16 mph) over the standard 40/60. Unfortunately, the additional weight meant rendered it no faster although the appearance certainly was memorable. The 40/60 used an overhead valve (OHV) in-line four cylinder engine with a displacement of 6.1 litres (371 cubic inches) with a rating of 70 HP (51 kW).

It took the industry some decades to work out that while men might be signing the checks (cheques), women exerted much influence on the choice of car to be purchased and as early as the 1930s some manufacturers did add women to their design teams for "look and feel" stuff like interiors (it took longer for them to infiltrate the engineering offices). Countess Ricotti however made her impact early. The shape of the Siluro Ricotti was optimized to achieve the best possible aerodynamic efficiency while providing enough internal space comfortably to accommodate six, the original benchmark the top-speed number. That proved illusory but, dictated by the fluid dynamics of air-flow, the radiator and engine had been placed within the passenger compartment and while this had certain advantages, it also meant heat soak through the aluminium skin and a tendency for the cabin to fill with fumes of gas (petrol) and oil. That was what the countess disliked and she refused to let her children be driven in the thing. The count had envisaged it as the ideal family car so in a spirit of marital compromise had Carrozzeria Castagna remove most of the roof, turning it into a kind of phaeton to be enjoyed during Milan's many warm, sunny days.

Sometime during Italy's turbulent inter-war period the Siluro Ricotti was lost but over two years during the 1970s, Alfa Romeo's engineers, using old photos and the extant original blueprints, created a replica on a surviving 40/60 chassis. That machine is now on display at the Alfa Romeo Historical Museum in Arese and the website confirms the top speed as only the 139 km/h (86 mph) the factory had verified for the Corsa (racing) version of the 40-60 which used distinctly non-aerodynamic bodywork but with an engine tuned to deliver 73 HP (54 kW).