Superbird (pronounced soo-per-burd)

(1) A one-year version of the Plymouth Road Runner with

certain aerodynamic enhancements, built to fulfil the homologation

requirements for use in competition.

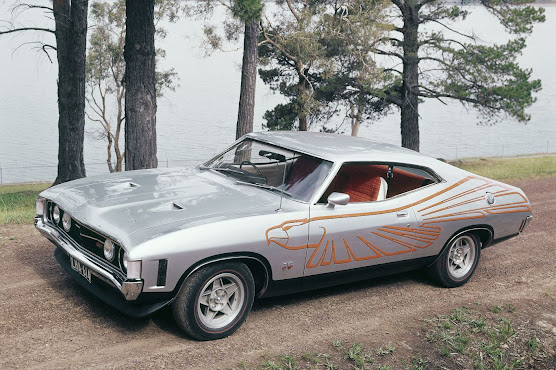

(2) A one-off Ford Falcon XA GT built by Ford Australia for

the motor show circuit in 1973 (and subsequently a derived (though much

toned-down) regular production model offered for a limited time).

1969: The construct was super + bird. The Middle English super was a re-purposing of

the prefix super, from the Latin super, from the Proto-Italic super, from the primitive Indo-European upér (over, above) and cognate with the

Ancient Greek ὑπέρ (hupér).

In this context, it was used as an adjective suggesting “excellent

quality, better than usual; wonderful; awesome, excellent etc. Bird was from the Middle English bird & brid,

from the Old English bridd (chick, fledgling, chicken). The origin was a term used of birds that

could not fly (chicks, fledglings, chickens) as opposed to the Old English fugol

(from which English gained the modern “fowl”) which was the general term for “flying

birds”. From the earlt to mid-fourteenth

century, “bird” increasingly supplanted “fowl” as the most common term. Superbird is a noun; the noun plural is Superbirds

and an initial capital is appropriate for all uses because Superbird is a

product name.

Of super- and supra-

The super- prefix was a learned

borrowing of the Latin super-, the

prefix an adaptation of super, from

the Proto-Italic super, from the

primitive Indo-European upér (over,

above) and cognate with the Ancient Greek ὑπέρ

(hupér). It was used to create forms conveying

variously (1) an enhanced sense of inclusiveness, (2) beyond, over or upon (the

latter notable in anatomy where the a super-something indicates it's

"located above"), (3) greater than (in quantity), (4) exceptionally

or unusually large, (5) superior in title or status (sometimes clipped to

"super"), (6) of greater power or potency, (7) intensely, extremely

or exceptional and (8) of supersymmetry (in physics). The standard antonym was “sub” and the

synonyms are listed usually as “on-, en-, epi-, supra-, sur-, ultra- and hyper-”

but both “ultra” and “hyper-” have in some applications been used to suggest a

quality beyond that implied by the “super-” prefix. In English, there are more than a thousand

words formed with the super- prefix. The supra- prefix was a learned

borrowing from the Latin suprā-, the

prefix an adaptation of the preposition suprā,

from the Old Latin suprād & superā, from the Proto-Italic superād and cognate with the Umbrian subra.

It was used originally to create forms conveying variously (1) above,

over, beyond, (2) greater than; transcending and (3) above, over, on top (in anatomy

thus directly synonymous with super) but in modern use supra- tends to be

differentiated in that while it can still be used to suggest “an enhanced

quality or quantity”, it’s now more common for it to denote physical position

or placement in spatial terms.

Superbirds of the northern & southern hemispheres

1969 Dodge Daytona (red) & 1970 Plymouth Road Runner Superbird (blue).

The Plymouth Superbird was a "homologation special" build only for the 1970 model year. By the mid 1950s, various NASCAR (National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing) competitions had become wildly popular and the factories (sometimes in secret) provided support for the racers. This had started modestly enough with the supply of parts and technical support but so tied up with prestige did success become that soon some manufacturers established racing departments and, officially and not, ran teams or provided so much financial support some effectively were factory operations. NASCAR had begun as a "stock" car operation in the literal sense that the first cars used were "showroom stock" with only minimal modifications. That didn't last long, cheating was soon rife and in the interests of spectacle (ie higher speeds), certain "performance enhancements" were permitted although the rules were always intended to maintain the original spirit of using cars which were "close" to what was in the showroom.

Lindsay Lohan, as superbird, generative AI (artificial intelligence) rendering by Stable Diffusion. The cheating didn't stop although the teams became more adept in its practice. One Dodge typified the way manufactures used the homologation rule to effectively game the system. The homologation rules (having to build and sell a minimum number of a certain model in that specification) had been intended to restrict the use of cars to “volume production” models available to the general public but in 1956 Dodge did a special run of what it called the D-500 (an allusion to the number built to be “legal”). Finding a loophole in the interpretation of the word “option” the D-500 appeared in the showrooms with a 260-hp V8 and crossed-flag “500” emblems on the hoods (bonnet) and trunk (boot) lids, the model’s Dodge’s high-performance offering for the season. However there was also the D-500-1 (or DASH-1) option, which made the car essentially a race-ready vehicle and one available as a two-door sedan, hardtop or convertible (the different bodies to ensure eligibility in NASCAR’s various competitions). The D-500-1 was thought to produce around 285 hp from its special twin-four-barrel-carbureted version of the 315 cubic inch (5.2 litre) but more significant was the inclusion of heavy-duty suspension and braking components. It was a successful endeavour and triggered both an arms race between the manufacturers and the ongoing battle with the NASCAR regulators who did not wish to see their series transformed into something conested only by specialized racing cars which bore only a superficial resemblance to the “showroom stock”. By the 2020s, it’s obvious NASCAR surrendered to the inevitable but for decades, the battle raged.

1970 Plymouth Superbird (left) and 1969 Dodge Daytona (right) by Stephen Barlow on DeviantArt. Despite the visual similarities, the aerodynamic enhancements differed between the two, the Plymouth's nose-cone less pointed, the rear wing higher and with a greater rake.

By 1969 the NASCAR regulators had fine-tuned their rules restricting engine power and mandating a minimum weight so manufacturers resorted to the then less policed field of aerodynamics, ushering what came to be known as the aero-cars. Dodge made some modifications to their Charger which smoothed the air-flow, labelling it the Charger 500 in a nod to the NASCAR homologation rules which demanded 500 identical models for eligibility. However, unlike the quite modest modifications which proved so successful for Ford’s Torino Talladega and Mercury’s Cyclone Spoiler, the 500 remained aerodynamically inferior and production ceased after 392 were built. Dodge solved the problem of the missing 108 needed for homologation purposes by introducing a different "Charger 500" which was just a trim level and nothing to do with competition but, honor apparently satisfied on both sides, NASCAR turned the same blind eye they used when it became clear Ford probably had bent the rules a bit with the Talladega.

The rear

wings (like the nosecone, the units on the Daytona and Superbird were not interchangeable,

the wings having different dimensions and set at different angles) genuinely

were there for the aerodynamic advantage they conferred others saw

possibilities for repurposing. Most of

the photographs (left) of “washing hanging out to dry” from a wing were stage

for comic effect but, between events, racing drivers really would use the

structure as a play to air their sweaty race suits. For amateur and profession photographers

alike, the wings also proved an irresistible prop which could be adorned by

young ladies. Had OnlyFans existed in

the era, it can be guaranteed some content providers would have been juxtaposed

against a Superbird’s wing.

Not discouraged by the aerodynamic setback, Dodge recruited engineers from Chrysler's aerospace & missile division (which was being shuttered because the Nixon-era détente had just started and the US & USSR were beginning their arms-reduction programmes) and quickly created the Daytona, adding to the 500 a protruding nosecone and high wing at the rear. Successful on the track, this time the required 500 really were built, 503 coming of the line. NASCAR responded by again moving the goalposts, requiring manufacturers to build at least one example of each vehicle for each of their dealers before homologation would be granted, something which typically would demand a run well into four figures. Plymouth duly complied and for 1970 about 2000 Superbirds (NASCAR acknowledging 1920 although Chrysler insists there were 1,935) were delivered to dealers, an expensive exercise given they were said to be invoiced at below cost. Now more unhappy than ever, NASCAR lawyered-up and drafted rules rendering the aero-cars uncompetitive and their brief era ended.

The graphic for the original Road Runner (1968, left) and the version used for the Superbird (1970, right). Both were created under licence from Warner Brothers, like the distinctive "beep-beep" horn sound, the engineering apparently as simple as replacing the aluminium strands in the mechanism with copper windings. The fee for the name was US$50,000 with the rights to the "beep-beep" invoiced at a further US$10,000.

Discounted Superbird, 1970. When new, the seriously weird looking machines often lingered on lots and deals had to be done; nobody could have anticipated what they'd become a half-century on.

So extreme in appearance were the cars (at some angles, distinctly ungainly) they proved at the time sometimes hard to sell and as well as being heavily discounted, some were converted back to the standard Road Runner specification by dealers anxious to get them out of the showroom. Views changed over time and they're now much sought by collectors, the record price known price paid for a Superbird being US$1,650,000 for one of the 135 fitted with the 426 Street Hemi. Despite the Superbirds having been produced in some four times the quantity of Daytonas, collectors indicate the're essentially interchangeable with the determinates of price (all else being equal) being determined by (1) engine specification (the Hemi-powered models the most desirable followed by the 6-BBL Plymouths (there were no Six-Pack Daytonas built) and then the 4 barrel 440s), (2) transmission (those with a manual gearbox attracting a premium) and (3) the combination of mileage, condition and originality. Mapped on to that equation is the variable of who happens to be at an auction on any given day, something unpredictable. That was demonstrated in August 2024 when a highly optioned Daytona in the most desirable configuration achieved US$3.36 million at Mecum’s auction at Monterey, California.

1969 Plymouth Road Runner advertisement.

The price was impressive but what attracted the interest of the amateur sociologists was the same Daytona in May 2022 sold for US$1.3 million when offered by Mecum at their auction held at the Indiana State Fairgrounds. The US$1.3 million was at the time the highest price then paid for a Hemi Daytona (of the 503 Daytonas built, only 70 were fitted with the Hemi and of those, only 22 had the four-speed manual) and the increase in value by some 250% was obviously the result of something other than the inflation rate. The consensus was that although the internet had made just about all markets inherently global, local factors can still influence both the buyer profile and their behaviour, especially in the hothouse environment of a live auction. Those who frequent California’s central coast between Los Angeles and San Francisco include a demographic not typically found in the mid-west and among other distinguishing characteristics there are more rich folk, able to spend US$3.36 million on a half-century old car they’ll probably never drive between the purchase and offering again at auction. That’s how the collector market works, the cars now essentially the same sort of commodity as paintings or other pieces of art. Still, it's a volatile market and some who "overpaid" by buying in a "peak market" have booked considerable losses when compelled to sell when demand proved less buoyant.

The Buick Skylark Grand Sport which in 1965 didn't become a Superbird.

Plymouth

paid Warner Brothers US$50,000 to licence the Road Runner trademark but

“Superbird” was free to use which must have been pleasing, the avian reference

an allusion to the big wing at the rear.

Curiously, had Buick a half-decade earlier decided to pursue what seems

in retrospect a “sales department thought bubble”, Plymouth would have had to

come up with something else because in 1965 Buick did run a one-off advertisement

for their new Skylark Grand Sport (the marque’s toe in the muscle car water)

with the copy headed “Superbird”. It may seem strange Buick had been tempted to

enter the muscle car business because, by the time Alfred P Sloan’s (1875–1966;

president of General Motors (GM) 1923-1937 and Chairman of the Board 1937-1946)

had settled down in 1940, Buick was second only to Cadillac in the GM corporate

hierarchy with Chevrolet at the bottom, followed by Pontiac and

Oldsmobile. However, the unexpected

success the year earlier of Pontiac’s GTO had proved an irresistible

temptation: there were profits to be made.

As it was, Cadillac was the only GM division in the era not to sell a

muscle car although the 1970 Eldorado was rated at 400 horsepower (HP), a

bigger number than many muscle cars although bizarrely, it was FWD (front wheel

drive) and has never been thought part of the ecosystem.

1936 Buick Century.

Debatably the the Buick Century was the "first muscle car" and although in the mid 1930s some fanciful names appeared, it's unlikely anyone would have thought of "Road Runner" or "Superbird", "Century" (denoting the 100 mph (160 km/h) speed all were said to be able to achieve) thought both distinctive and informative. The definition of “muscle car” is by some contested and the only consensus seemes to be none believe it can encompass FWD (front-wheel-drive), despite Cadillac in 1970 rating the Eldorado's 500 cubic inch (8.2 litre) V8 at at stellar 400 HP which was 25 more than Ford claimed for the Boss 429 Mustang which used a slightly detuned racing engine. Ford of course understated things but is is an amusing comparison. The definition most prefer is: “a big engine from a

big, heavy car installed in a smaller, lighter car” and for Buick, the approach

really wasn’t novel. Although in 1936 the

improvement in the economy remained patchy (and would soon falter), Buick rang

in the changes, re-naming its entire line.

Notably, one newly designated offering was the Century, a revised

version of the model 60, created by replacing the 233 cubic inch (3.8 litre)

straight eight with the 320 cubic inch (5.2 litre) unit from the longer,

heavier Roadmaster. Putting big engines

into small cars was nothing new and during the interwar years some had taken

the idea to extremes, using huge aero-engines, but those tended to be one-offs

for racing or LSR (land speed record) attempts. In

Europe, (slightly) larger engines were sometimes substituted and British manufacturers

often put six cylinder power-plants where once there had been a four but their

quest was usually for smoothness and refinement rather than outright speed and

the Century was really the first time a major manufacturer had used the concept

in series production and by many it’s acknowledged as the last common ancestor

(LCA) of the muscle cars which in the 1960s came to define the genre.

1970 Buick GSX 455 Stage 1.

The model

which in 1965 Buick seemingly flirted with promoting as the “Superbird” was the

Skylark Grand Sport, built on the corporate intermediate A-Body shared with

Chevrolet, Pontiac & Oldsmobile. In

its first season the Grand Sport was an option rather than a model and it used

the 401 cubic inch (6.6 litre) Buick “Nailhead” V8 which technically violated

GM’s corporate edict placing a 400 cubic inch displacement limit on engines in

intermediates but this was “worked around” by “rounding down” to 400 for

purposes of documentation and for that there was a precedent; earlier Pontiac’s

336 cubic inch (5.5 litre) V8 contravened another GM rule and PMD solved that

problem by claiming the capacity was really 326 (5.3) and, honor apparently

satisfied on both sides, it was back to business as usual. The Grand Sport option proved a success in

and by 1967 the package was elevated to a model as the GS 400, Buick’s new big-block

engine a genuine 400 cid (there were also small-block Skylark GSs appropriately

labelled GS 340 and later GS 350) and on the sales charts it continued to

perform well, but, being a Buick, its appearance was more restrained than the

muscle cars from the competition (including those from other GM divisions) so

it tended to be overshadowed but this changed in 1968 when the “Stage 1” option

was introduced as a dealer-installed option.

What this did was r increase power and torque and optomize the delivery

of both for quarter-mile (402 m) sprints down drag strips and as a

proof-of-concept exercise it must have worked because in 1969 the Stage 1

package appeared on the factory’s official option list. When tested, it performed (on the drag strip)

so well it was obvious the official output numbers were under-stated but thing

really clicked the next year when Buick enlarged the V8 to 455 cubic inches

(7.5 litre), delivering 510 lb⋅ft (691 N⋅m) of torque, the highest rating in the industry. It's often claimed Detroit wouldn't top this until the second generation Dodge Viper (ZB I, 2003-2006) debuted with its

V10 enlarged to 506 cubic inches (8.3 litres) but the early 472 (1968) & 500 (1970) cubic inch (7.7 & 8.2 litre) Cadillac V8s were rated respectively at 525 lb⋅ft (712 N⋅m) & 550 lb⋅ft (746 N⋅m).

1970 Buick GSX brochure.

Buick in 1970 made available the GSX “Performance and Handling Package” which

added a hefty US$1,100 to the GS 455’s base price US$3,098, a factor in it

attracting only 678 (presumably most-content) buyers. The straight-line performance was

impressive. While it couldn’t match the

ability of genuine race-bred engines like the Chrysler Street Hemi, Ford Boss

429 or the most lusty of the big-block Chevrolets effortlessly to top 140 mph

(225 km/h), on the drag strip, the combination of the prodigious low-speed

torque and relatively light weight meant it could be a match for just about

anything. The use of “Stage 1” of course

implied there would be at least a “Stage 2” (a la Pontiac’s Ram Air II, III etc)

but the world was changing and only a handful of "Stage 2" components were assembled and shipped to dealers. While both the GSX and

Stage 1 would live until 1972, 1970 would be peak Buick muscle.

1967 Dodge Coronet R/T advertisement.

Another

footnote to the tale is that in 1967, some time before Plymouth released the

Road Runner, Dodge (Plymouth’s corporate stable-mate) published an

advertisement for the Coronet R/T (Road/Track) which must have been ticked off

by the legal department because cleverly it included the words “road” and

“runner” arranged in such as way a viewer would read them as “Road Runner”

without them appearing in a form which would attract a C&D (cease &

desist letter) from Warner Brothers. Obviously, the tie-in with Road/Track was the idea of a machine suited both to street and competition use and the

agency must have congratulated themselves but the satisfaction would have been

brief because within hours of the advertisement appearing in magazines on

newsstands, Chrysler’s corporate marketing division instructed Dodge to “pull

the campaign”. By then, Plymouth’s plans

for the surprise release in a few months of the appropriately licensed “Road

Runner” were well advanced and they didn’t want any thunder stolen. The Dodge advertisement remained a one-off

but the division must have wished they’d thought of using “Road Runner” themselves

because the Super Bee (their later take on the Road Runner concept) only ever sold a

quarter of the volume of Plymouth’s original; it pays to be first but a flaky

name like “Super Bee” can’t have helped.

Subsequently, the names Road Runner & Roadrunner (the latter which,

without the initial capital, is the taxonomic term for the bird (genus

Geococcyx and known also as chaparral birds or chaparral cocks) Warner

Brothers' Wile E. Coyote could never quite catch) have been used for products

as varied as a Leyland truck, many sports teams, computer hardware &

software and a number of publications.

Don't mess with popular and respected birds.

However,

just because Chrysler’s lawyers dotted the i's and crossed the t's with Warner

Brothers didn’t mean their involvement with the Plymouth Road Runner was done. Shortly after the Road Runner was released

late in 1967, the corporate office became aware “...certain Chrysler-Plymouth Division dealers in the

Southwest [were] using live Roadrunner birds in local sales promotions and

offering cash rewards for the capture of live specimens.”

That would at the time have seemed to dealers just a clever marketing gimmick

but consulted, the legal department determined it was “...against

Federal Law to hunt, capture kill, sell or offer to purchase a nonautomotive

Roadrunner.” Further to clarify, it was added Roadrunners

were “…none-game

birds classified as national resources and protected by Federal and

International law.” Who knew?

In the C&D letter Chrysler-Plymouth's public

relations manager circulated to all dealers, the cultural significance was also

mentioned, the Roadrunner described as a “...popular and respected bird... particularly in New

Mexico where it is honored as the state's official bird.” Accordingly, the corporate directive banned “...any future use

of live Roadrunners in promotional activities.”

1970 Plymouth Road Runner with a Warner Brothers' interpretation of the genus Geococcyx in fibreglass.

So using live examples of

the “popular

and respected bird” was out but the marketing department wasn’t

deterred and for promotional purposes later arranged production in fibreglass

of large representations of the Roadrunner, designed to emerge, grinning and wide-eyed

through the hood (bonnet) scoop (which Chrysler called the “air-grabber”

because it did what it said on the tin: funnelled desirable cold air straight

to the induction system). Being advertising,

the large plastic structure owed much to the Warner Brothers depiction of the

creature and little to how evolution had produced genus Geococcyx. Some of the fibreglass promotional props

survived to be exhibited protruding through a Road Runners air-grabber and die-cast models of the ensemble (car plus “popular and respected bird”) sometimes are available.

Australia's Ford Falcon Superbirds

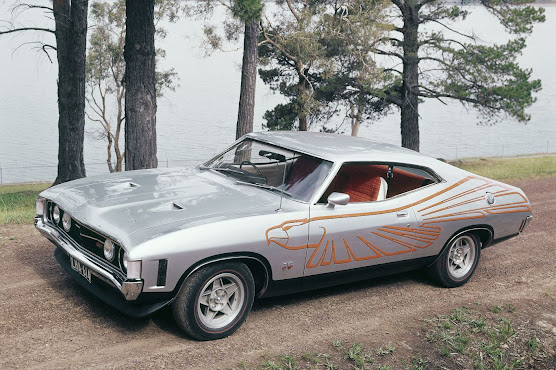

1973 XA Ford Falcon GT Superbird, built for the show circuit.

Based on the then-current XA Falcon GT Hardtop, Ford Australia’s original Superbird was a one-off created for display at the 1973 Sydney and Melbourne Motor Shows, the purpose of the thing to distract attention from Holden’s new, four-door Monaro model, a range added after the previous year’s limited production SS had generated sufficient sales for the “proof-of-concept” to be judged a success. Such tactics are not unusual in commerce and Ford were responding to the Holden’s earlier release of the SS being timed deliberately to steal the thunder expected to be generated by the debut of the Falcon Hardtop. Although it featured a new "rough-blend" upholstery and a power-steering system with the rim-effort increased from 4 to 8 lbs (1.8 to 3.6 kg), mechanically, the Superbird show car was something of a “parts-bin special” in that it differed from a standard GT Hardtop mostly in the use of some of the components orphaned when the plan run of 250-odd (Phase 4) Falcon GTHOs was cancelled after in 1972 a Sydney tabloid newspaper had stirred a moral panic with one of their typically squalid and untruthful stories about “160 mph (258 km/h) supercars” soon to be available to males ages 17-25 (always a suspect demographic in the eyes of a tabloid editor). Apparently, it was a “slow news day” so the story got moved from the sports section at the back to the front page where the headline spooked the politicians who demanded the manufacturers not proceed with the limited-production specials which existed only to satisfy the homologation rules for competition. Resisting for only a few days, the manufacturers complied and within a week the nation’s regulatory body for motor sport announced the end of “series-production” racing and that in future the cars used on the track would no longer need to be so closely related to those available in showrooms.

1973 XA Ford Falcon GT Superbird with model in floral dress.

The Falcon GT Superbird displayed at the motor shows in 1973 however proved something of a harbinger in that it proved a bit of a “trial run” for future ventures in which parts intended solely for racing would be added to a sufficient number of vehicles sold to the public to homologate them for use on the circuits. In that sense, the mechanical specification of the Superbird previewed some of what would later in the year be supplied (with a surprising amount of car-to-car variability) in RPO83 (regular production option 83) including the GTHO’s suspension settings, a 780 cfm (cubic feet per minute) carburetor, the 15” x 7” aluminium wheels, a 36 (imperial) gallon (164 litre) fuel tank and some of the parts designed for greater durability under extreme (ie on the race track) conditions. Cognizant of the effect the tabloid press has on politicians, none of the special runs in the immediate aftermath of the 1972 moral panic included anything to increase performance.

Toned down: 1973 Ford Falcon 500 Hardtop with RPO77 (Superbird option pack) in Polar White with Cosmic Blue accents over White vinyl interior.

Most who saw the Superbird probably didn’t much dwell on the mechanical intricacies, taken more by the stylized falcon which extended for three-quarters the length of the car. It was the graphic which no doubt generated publicity in a way the specification sheet never could and it was made available through Ford dealers but the take-up rate was low so which it was decided to capitalize on the success of the show car by releasing a production Superbird (as RPO77), the graphic had been reduced to one about 18 inches (450 mm) in length which was applied to the rear quarters, an ever smaller version appearing on the glovebox lid. In keeping with that restraint, RPO 77 included only “dress-up” items and a 302 cubic inch (4.9 litre) V8 in the same mild-mannered state of tune as the versions sold to bank managers and such and very different from the high-compression 351 (5.8) in the show car. Still, RPO 77 did succeed in stimulating interest in the two-door Hardtop, sales of which had proved sluggish after the initial spike in 1972; some 700 seem to have been built (from a projected 750) and that all but 200 were fitted with an automatic transmission was an indication of the target market. In Australia, the surviving Superbirds are now advertised for six figure sums while the surviving three Phase 4 GTHOs (the fourth was destroyed in a rally which seems an improbable place to use such a thing) can command over a million. The 1973 show car was repainted from "Pearl Silver" to its original "Wild Violet" before being sold.

The Melbourne Motor Show Superbird, unused image from a publicity photo session, Melbourne, 1973.

As a footnote, the 302 V8 was exclusive to Australia in being based on the US Cleveland (335) engine which there was the basis only for 351 and 400 (6.6) versions. The rationale for the Australians developing their unique "302 Cleveland" was one of production-line standardization, the local operation having never produced the Windsor line of V8s which by 1969 provided the US market with both 302 & 351 versions. According to the convention in use at the time, the Australian engines could have been dubbed "302 Geelong" & "351 Geelong" (Geelong the city where the Ford foundry was located) but that was never adopted and both tend to be called "Australian Clevelands". Creating the 302 Cleveland wasn't challenging or expensive and both the Australian engines were (with detail differences between them) a single-configuration compromise optimized for use on the street, eschewing use of the components which delivered improved top-end power (as fitted to some of the US engines) which worked well at high speed but were not ideal for street use where a progressive curve of low and mid-range torque is the most desired characteristic. What the Australian engineers did for their 351 was was combine the large (61-64 cm3) combustion chambers from the US "4V" heads (ie "4 venturi" indicating the use with a four barrel carburettor) with the smaller "2V" intake ports, the arrangement producing a good quench and air/fuel swirl through the ports, enhancing the low-to-mid range torque output. The short-stroke Australian 302 was different in that it used a 56.4–59.4

cm3 combustion chamber in conjunction with the high-swirl, small ports. That combination ("closed" combustion chamber & small ports) turned out to be a "sweet-spot" for street use which has made the Australian 302 heads a popular item for those modifying 351s, the swap made possible by the shared bore. While the Cleveland suffered fundamental flaws (excessive weight and poor lubrication), the canted-valve heads were right from day one, the reason why the 1969 Boss 302 (which put the Cleveland heads on the well-lubricated Windsor block) was so highly regarded. Although its sounds oxymoronic, Ford Australia really did position its 302 as "an economy V8" but that phrase needs to be read as a comparative and not an absolute.

%201967%20Ad.jpg)