Flounce (pronounced flouns)

(1) To

go with impatient or impetuous, exaggerated movements.

(2) To

throw the body about spasmodically; flounder.

(3) An

act or instance of flouncing; a flouncing movement.

(4) A

strip of material gathered or pleated and attached at one edge, with the other

edge left loose or hanging: used for trimming, as on the edge of a skirt or

sleeve or on a curtain, slipcover etc.

1535–1545:

Of obscure and contested origin. Some

sources suggest something akin to words from old dialectal Scandinavian forms

such as the Norwegian flunsa (to

hurry) or the Swedish flunsa (to

plunge; to splash) but the first record of these is two centuries after the

English is first documented. Thus more

preferred is a derivation of the obsolete Old French frounce (wrinkle), from the Germanic froncir (to wrinkle) and the eventual spelling in English was

probably influenced by bounce. Notions

of "anger, impatience" began to adhere to the word during the

eighteenth century although, as a noun of motion, use dates from the 1580s. The use to describe “an ornamental gathered

ruffle sewn to a garment by its top edge” (a kind of ruffle) was first noted in

1713, from the fourteenth century Middle English frounce (pleat, wrinkle, fold) from the Old French fronce & frounce (line, wrinkle; pucker, crease, fold) from the Frankish hrunkjan (to wrinkle), ultimately

derived from the Proto-Germanic hrunk. Flounce, flounciness & flouncing are nouns & verbs, flounced is a verb, flouncier, flounciest & flouncey are adjectives and flouncily is an adverb; the noun plural is flounces. In the industry, "flouncy" is sometimes used as noun, applied to garments flouncier than most.

Ruffle (pronounced ruhf-uhl)

(1) To

destroy the smoothness or evenness of; to produce waves or undulations.

(2) In avian

behaviour, for a bird to erect the feathers, usually to convey threat, defiance

etc.

(3) To

disturb, vex, or irritate; disturbance or vexation; annoyance; irritation; a

disturbed state of mind; perturbation.

(4)

Rapidly to turn the pages of a book.

(5) In

the handling of playing cards, rapidly to pass cards through the fingers while

shuffling.

(6) In

tailoring, to draw up cloth, lace etc, into a ruffle by gathering along one

edge.

(7) In

military music, in the field of percussion, the low, continuous vibrating

beating of a drum, quieter than a roll (also called a ruff).

(8) To

behave riotously; an arrogantly display; a swagger (obsolete).

(9) In

zoology, the connected series of large egg capsules, or oothecae, of several

species of American marine gastropods of the genus Fulgur.

(10) In LGBTQQIAAOP slang, the passive partner in a lesbian

relationship, known also as a “fluff”.

1250-1300:

From Middle English ruffelen, possibly

from the Old Norse hruffa & hrufla (to graze, scratch) or the Middle

Low German ruffelen (to wrinkle,

curl) but beyond that the origin is unknown. It was related to the Middle Dutch ruyffelen and the German & Low

German ruffeln. The meaning "disarrange" (hair or

feathers) dates from the late fifteenth century; the sense of "annoy,

distract" is from the 1650s. As one

could become ruffled, so too one be unruffled, that adjectival form dating from

the 1650s. The literal meaning, in

reference to feathers, leaves and such was first recorded in 1816.

The use in dressmaking to describe “an ornamental frill" is attested from 1707, derived from the verb ruffle. Related stylistically to the ruffle is the ruff in the sense of the large, stiffly starched collar especially common in the seventeenth century, a style which dated from the 1520s; used originally in reference to sleeves, it came to be applied to collars after the 1550s, almost certainly a a shortened form of ruffle which described something physically much bigger. As applied to playing cards, it’s actually a separate word, dating from the 1580s, from a former game of that name. In this context, word is from the French roffle, from the early fifteenth century romfle, from the Italian ronfa, possibly a corruption of trionfo (triumph). The game was popular between 1590-1630. The now obsolete sense of an arrogant display or swagger is from the fifteenth century and the origin is obscure but may related to some perception of those who wore ruffs or ruffles. The meaning as used in the percussion section of military bands is from 1715–1725 and may have been imitative of the drum sound.

As a general principle, a ruffle is created by the manipulation of a piece of fabric cut in the shape of a rectangle. Actual geometric precision is not required because depending on the garment and the effect desired, the shape may vary but it will at least tend towards the rectangular. The technique is to gather the fabric at the top into a smaller area; when this is sewn into a seam line, typically at the waist or neck-line, the pleats created by the gather will fall naturally, the swishing movement inherent in the fullness of the fabric being the ruffle. The outcome is determined by the fabric’s relationship of width and length and the weight and type of material used.

The first ruffles were probably nothing to do with fashion but merely a layered appendage to protective clothing, usually as a form of water-proofing. In the decorative sense, although antecedents can be identified in ancient Egyptian art, in their modern form they appeared first in the mid-fifteenth century as attachments to the collars of chemises which, as happens in fashion, grew in shape and complexity into the large and elaborated ruffled constructions associated with Tudor England. Since, although the flow and flourish has waxed and waned, the ruffle has never really gone away, despite the wishes of those who prefer more austere lines. The ruffle can also be a device, the design adaptable to either (1) add visual bulk to a small bustline or (2) disguise a large bustline.

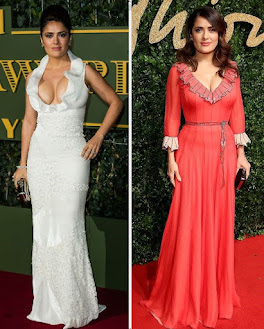

Lindsay Lohan, flouncing about in flounces.

The construction of a flounce differs in that the pattern tends always towards the circular, the cut technically the shape of a donut although those both ambitious and skillful can render flounces used both irregular and more complex curves although one often under-appreciated factor in success is the weight and flexibility of the material chosen: the outcome is determined by depth of the curve, the width of the fabric and the weight and type of material used. For a flounce successfully to work, it needs to “flounce” and the movement can be influenced as much by weight as cut. It’s the inner edge of the donut which, without any gather, is sewn into the seam while the outside edge of becomes the fullness at the hem, the volume created by virtue of the longer line. Because the inner edge is so much shorter, there’s not the same need to gather so the results tends to be soft billows of fabric rather than pleats. The same technique can be used to create a layered effect where the material flares out not at all but instead follow the line of the garment; this is achieved by a cut where the inner edge is much closer in length to the outer so the shape is closer to a crescent.

Ruffles and flounces are most associated with a wrap which extends around the garment but variations of the shape of the cuts and the

techniques of attachment are used whenever something voluminous needs to be

attached. Flounced and ruffled necklines and sleeves use the same rectangle

versus donut model as the larger interpretations, both often used in scalloped cuts.

Sometimes ruffled: The last King of Italy

Umberto Nicola Tommaso Giovanni Maria di Savoia (1904–1983) was the last king of Italy, his reign as Umberto II lasting but thirty-four days during May-June 1946; Italians nicknamed him the Re di Maggio (May king) although some better-informed Romans preferred regina di maggio (May queen). At the instigation of the US and British political representatives of the allied military authorities, in April 1944 he was appointed regent because it was clear popular support for Victor Emmanuel III (1869-1947; King of Italy 1900-1946) had collapsed. Despite Victor Emmanuel’s reputation suffering by association, his relationship with the fascists had often been uneasy and, seeking means to blackmail the royal house, Mussolini’s spies compiled a dossier (reputably several inches thick), detailing the ways of his son’s private life. Then styled Prince of Piedmont, the secret police discovered Umberto was a sincere and committed Roman Catholic but one unable to resist his "satanic homosexual urges” and his biographer agreed, noting the prince was "forever rushing between chapel and brothel, confessional and steam bath" often spending hours “praying for divine forgiveness.” After a referendum abolished the monarchy, Umberto II lived his remaining 37 years in exile, never again setting foot on Italian soil. His turbulent marriage to Princess Marie-José of Belgium (1906-2001) produced four children but historians consider it quite possible none of them were his.

No comments:

Post a Comment