Tactile (pronounced tak-til or tak-tahyl)

(1) Of, pertaining to, endowed with, or affecting the

sense of touch.

(2) Perceptible to the touch; tangible.

(3) Capable of being touched; tangible (archaic).

1605–1615: From the Middle French tactile, from the Latin tāctilis

(tangible), from tāctus, past participle

of tangere (to touch)), from the

primitive Indo-European root tag (to touch; to handle). The construct was tact(us) + ile. The –ile suffix was from the Latin –īlis (neuter -ile, comparative -ilior,

superlative -illimus or -ilissimus; the third-declension

two-termination suffix), from the Proto-Italic -elis, from the primitive Indo-European -elis, from -lós. It was used to form an adjective noun of

relation, frequently passive, to the verb or root. The meaning "of or pertaining to the

sense of touch" is attested from the 1650s. Tactile is an adjective; tactility is a noun.

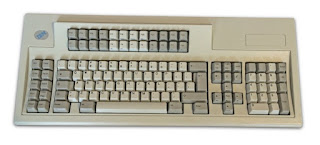

In

the few decades computing has been a mainstream activity, there has been such a

variety of hardware, operating systems, languages and software at various points

in the application layers, that there’s little general agreement about what’s

best in any particular field but most with any exposure to the IBM Model M

keyboard agree it’s probably the finest keyboard ever made. Even those not attracted to the tactility

which is its most obvious feature (and there are those who prefer a “squishy” to

a “clicky” keyboard) will usually concede the build quality is exceptional, compared

especially to some of the sad devices bundled with systems in recent years. It shouldn’t be surprising IBM was able to

build something like the Model M keyboard at scale given the company’s decades

of experience in engineering a construction and there are Model M nerds prepared

to believe all those years were but preparation for what was required to make

the tactile devices.

International

Business Machines (IBM) began in New York in 1888 (adopting the IBM name in 1924), its early core-business mechanical

“tabulating systems” for accounting and time-keeping and by the 1930s, some of

the mechanical engineering used in these systems was applied to typewriter

technology after it acquired the tools, patents and production facilities of

Electromatic Typewriters of Rochester. The

result of the R&D effort was the Model 01 IBM Electric Typewriter which was

released in 1935 and became the first really successful electric typewriter in

the US, the beginning of a line which, in 1961 produced the IBM Selectric, famous for its “element”

which the rest of the world called the “golfball”. The almost spherical “golfball” (which

appears in some IBM documents both also as “typeball”) contained the

impressions of the letters which struck the ribbon and was interchangeable with

other made with other font sets. That

was not a new idea, other manufacturers using the principle of interchangeability

in the late nineteenth century but with “type wheels” which were larger and

tended to be fragile, the three-dimensional “golfball” both more robust and,

having to travel a smaller distance per key stroke, permitting a faster typing

rate. It was with the Selectric that the

evolution of what became the Model M keyboard really began.

The first version of the definitively tactile,

stand-alone IBM keyboard was the Model 14 which, although most associated with

the original IBM PC-1 released in August 1981, had actually debuted with the System/23

Datamaster (1981-1985), a short-lived corporate workstation which proved a

dinosaur, unable to compete with the IBM PC, the success of which was also the

death knell for the earlier 6580 Displaywriter (1980-1986) which had actually

enjoyed some success as a hefty and expensive but capable corporate

word-processor. The Datamaster,

introduced just five weeks prior to the PC-1, used the same Model 14 keyboard,

initially with an 83 key layout and the nerdiest of nerds note its technical

superiority over the Model M in that it uses a buckling spring over a

capacitive PCB (printed circuit board) rather than the later membrane. The Model F remained in general production

until 1985, being then built in limited numbers (by both IBM and Lexmark) until

1985 and was notable for innovations such as the revisions to the layout to

accommodate the PC-AT protocols and the availability of specialized models with

as few as 50 or as many as 127 keys.

Model F aficionados

can be snobby, pointing out even IBM admitted one of the design objectives with

the Model M was to reduce manufacturing costs but their attraction is real, the

intricacies of the Model F intriguing and their labour-intensive production

process does mean nothing like them is likely again to be made. The internal assembly uses two curved metal

back-plates and the PCB is flexible, thus also curved when attached to the back-plate

and while just about every other keyboard's curves are simulated by the molding

of the keycap profiles, the Model F's curve is integral to the frame, thus

allowing all keycaps to be the same shape and size, a great advantage for those

who like to tinker and customize. Freaks

customizing keyboards are perhaps less frequently found than once they were but

still exist in dark rooms living on pizza and Coca-Cola. Snobbery or not, the freaks do have a point (up to a point) because the mechanical advantages are real. The capacitive design is superior, requiring

a lighter actuation force and delivering a crisper feel and a slightly sharper feedback;

it’s also more robust, IBM guaranteeing each key with a MTBF (mean time between

failure) of over 100 million key-presses, a reasonable life even for the most productive trolls.

The switch from PCBs to membranes meant these characteristics were to

some degree toned down in order to lower manufacturing costs although the MTBF

was still rated an impressive 80 million.

Pace the freaks but the Model M is

preferable, if for no other reason than simply because it (more-or-less) standardized

the core keyboard layout (most others now conform) and in use, the tactility is little different from its predecessor. Regarding the layout, the case can be made

that the Model F’s location of the function keys to the left may actually make

more sense but the planet has settled on the Model M layout. Introduced in 1985 with the 3161 terminal,

the PC-compatible version appeared in 1987 when it was included with the PS/2. In use the Model M is a solid (9 lb (4 kg))

tactile experience which feels little different from the Model F and users have

a long time to become accustomed to that feel; the keyboards, the oldest of

which are now some forty years old, appearing not to have a life expectancy,

many in continuous use for decades and a servicing ecosystem exists should any

parts need to be replaced although it’s said rectifying the consequences of spills

(of coffee, red wine, G&Ts etc) is a more common request. The best source for the tactile IBMs is

ClickyKeyboards.

It will be appreciated with regard to the

figures that depression of the key button 1 moves the key button and its stem 6

into the housing 3, creating longitudinal compression and lateral deflection of

the helical compression spring 2. An initial counter-clockwise moment is

exerted on the rocker member 4 which is approximately equal to the force F

times the distance between the pivot point 8 of the rocking member 4 and the

center line of the spring. The upper end of the helical spring 2 is held

squarely against the key button 1 by a clockwise moment created by a force

equal to approximately F times the diameter of the spring divided by two. The

rocker member 4 will initially be held firmly over the contacts 5A and 5B. As

the lateral motion of the center of the helical compression spring 2 increases,

both the top and bottom reaction moments in spring 2 are decreased because F is

transmitted through the center section of spring 2. Shortly after these moments

approach 0, the rocker member rocks to a position squarely over contacts 5A and

5C and the top of spring 2 rocks about the right hand edge of its topmost coil.

The constraints upon the depression column spring have changed from an initial

end clamped condition to an end clamped-pinned condition. This sudden change

provides the tactile response of the key and is accompanied by a sudden rocking

action of the rocker member 4 which creates an acoustic feedback as well.

The "buckling spring torsional snap actuator"

is the core of the Model M’s charm.

Unlike mechanical switches that are depressed straight down like plungers,

the Model M has springs under each key that contract, snap flat, or

"buckle," and then spring back into place when released. This provides the audible “click” so

associated with the model and which some don’t like but for those who become

accustomed to typing on one, it’s hard to go back to anything else; they have

the feel of a pre-modern (circa 1980 and earlier) Mercedes-Benz. Because of the physicality, typing on a Model

M is a tangible experience; like a typewriter, the tactility and the feedback

of the click gives every letter a physical presence.

IBM Model M user Lindsay Lohan in Life-Size (2000, Walt Disney Television).

No comments:

Post a Comment