Fecund (pronounced fuh-khunt, fee-kuhnd or fek-uhnd)

(1)

Producing or capable of producing offspring, fruit, vegetation, etc in

abundance; prolific; fruitful.

(2)

Figuratively, highly productive or creative intellectually; innovative.

Circa

1525: From the mid-fifteenth century Middle English fecounde from the Middle French fecund,

from the Old French fecund & fecont (fruitful), from the Latin fēcundus (fruitful, fertile, productive;

rich, abundant (and related to the Latin fētus

(offspring) and fēmina (“woman”)),

from fe-kwondo-, an adjectival suffixed

form of the primitive Indo-European root dhei

or dhe- (to suck, suckle), other derivatives

meaning also “produce” & “yield”. Fē in this case wasn’t a prefix but a

link to fetus whereas -cundus was the adjectival suffix. It replaced the late Middle English fecounde. The spelling fecund was one of the “Latinizing”

revisions to spelling which was part of the framework of early Modern English,

(more or less) standardizing use and replacing the Middle English forms fecond, fecound & fecounde. The Latin root itself proved fecund; from it

came also felare (to suck), femina (woman (literally “she who

suckles”)); felix (happy, auspicious,

fruitful), fetus (offspring,

pregnancy); fenum (hay (which seems

literally to have meant “produce”)) and probably filia (daughter) & filius

(son), assimilated from felios (originally

“a suckling”). The noun fecundity emerged

in the early fifteenth century and was from the Latin fecunditatem (nominative fecunditas)

(fruitfulness, fertility), from fecundus

(fruitful, fertile). The old spelling fœcund is obsolete. Fecund is an adjective and fecundity & fecundation

are nouns; the noun plural is fecundities.

In

his A Dictionary of Modern English Usage

(1926), Henry Fowler (1858–1933) noted without comment the shift in popular

pronunciation but took the opportunity to cite the phrase of a literary critic

(not a breed of which he much approved) who compared the words of HG Wells

(1866-1946) & Horace Walpole (1717–1797): “The fecund Walpole and the facund Wells”. The critic, Henry Fowler noted: “fished up

the archaic facund for the sake of

the play on words”. Never much impressed

by flashy displays of what he called a “pride of knowledge”, his objection here

was that there was nothing in the sentence to give readers any idea of the change

in meaning caused by the substituted vowel.

Both were from Latin adjectives, fēcundus

(prolific) and facundus (elegant).

Fertile (pronounced fur-tl or fur-tahyl

(mostly UK RP))

(1)

Of land, bearing, producing, or capable of producing vegetation, crops etc,

abundantly; prolific.

(2)

Of living creatures, bearing or capable of bearing offspring; Capable of growth

or development.

(3)

Abundantly productive.

(4)

Conducive to productiveness.

(5)

In biology, fertilized, as an egg or ovum; fecundated; capable of developing

past the egg stage.

(6)

In botany, capable of producing sexual reproductive structures; capable of

causing fertilization, as an anther with fully developed pollen; having

spore-bearing organs, as a frond.

(7)

In physics (of a nuclide) capable of being transmuted into a fissile nuclide by

irradiation with neutrons (Uranium 238 and thorium 232 are fertile nuclides);

(a substance not itself fissile, but able to be converted into a fissile

material by irradiation in a reactor).

(8)

Figuratively, of the imagination, energy etc, active, productive, prolific.

1425–1475:

From the Late Middle English fertil (bearing

or producing abundantly), from the Old French fertile or the Latin fertilis

(bearing in abundance, fruitful, productive), from ferō (I bear, carry) and .akin to ferre (to bear), from the primitive Indo-European root bher (to carry (also “to bear children”)). The verb fertilize dates from the 1640s in

the sense of “make fertile” although the use in biology meaning “unite with an

egg cell” seems not to have been used until 1859 and use didn’t become

widespread for another fifteen years.

The noun fertility emerged in the mid-fifteenth century, from the

earlier fertilite, from the Old

French fertilité, from the Latin fertilitatem (nominative fertilitas) (fruitfulness, fertility),

from fertilis (fruitful, productive). Dating from the 1660s, the noun fertilizer was

initially specific to the technical literature associated with agriculture in

the sense of “something that fertilizes (land)”, and was an agent noun from the

verb fertilize. In polite society, fertilizer

was adopted as euphemism for “manure” (and certainly “shit”), use documented

since 1846. The noun fertilization is

attested since 1857 and was a noun of action from fertilize; it was either a

creation of the English-speaking world or a borrowing of the Modern French fertilisation. The common antonyms are barren, infertile and

sterile. Fertile is an adjective, fertility,

fertilisation & fertileness are nouns, fertilize fertilized & fertilizing

are verbs. Technical terms like

sub-fertile, non-fertile etc are coined as required.

The

term “Fertile Crescent” was coined in 1914 was coined by US-born University of

Chicago archaeologist James Breasted (1865-1935); it referred to the strip of

fertile land (in the shape of an irregular crescent) described the stretching

from present-day Iraq through eastern Turkey and down the Syrian and Israeli

coasts. The significance of the area in

human history was it was here more than ten-thousand years ago that settlements

began the practice of structured, seasonal agriculture. The Middle English synonym childing is long obsolete but the more

modern term “at risk” (of falling pregnant) survives for certain statistical

purposes and was once part of the construct of a “legal fiction” in which the

age at which women were presumed to be able to conceive was set as high as 65;

advances in medical technology have affected this.

The difference

So

often are “fecund” & “fertile” used interchangeably that there may be case

to be made that in general use they are practically synonyms. However, the use is slanted because fertile

is a common word and fecund is rare; it’s the use of fertile when, strictly

speaking, fecund is correct which is the frequent practice. Technically, the two have distinct meanings although

there is some overlap and agriculture is a fine case-study: Fertile specifically

refers to soil rich in nutrients and able to support the growth of plants. Fecund can refer to soil capable of supporting

plant growth but it has the additional layer of describing something capable of

producing an abundance of offspring or new growth. This can refer to animals, humans, bacteria or

(figuratively), ideas. Used interchangeably,

expect between specialists who need to differentiate, this linguistic swapping

probably doesn’t cause many misunderstandings because the context of conversations

will tend to make the meaning clear and for most of use, the distinction between

a soil capable of growing plants and one doing so prolifically is tiresomely

technical. Still, as a rule of thumb,

fertile can be thought of as meaning “able to support the growth of offspring

or produce” while fecund implies “producing either in healthy volumes”.

Ultimate fecundity: Fast breeding

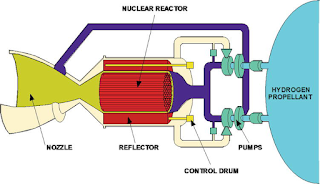

Although there are differences in meaning, fertile and fecund tend to be used interchangeably, especially in agriculture. As adjectives, the difference is that fecund means highly fertile whereas fertile is the positive side of the fertile/infertile binary; capable of producing crops or offspring. Fecundity may thus be thought a measure of the extent to which fertility is realised. In nuclear physics, fertile material is that which, while not itself fissile (ie fissionable by thermal neutrons) is able to be converted into fissile material by irradiation in a reactor. Three basic fertile materials exist: thorium-232, uranium-234 & uranium-238 and when these materials capture neutrons, respectively they are converted into uranium-233, uranium-235 & fissile plutonium-239. Artificial isotopes formed in the reactor which can be converted into fissile material by one neutron capture include plutonium-238 and plutonium-240 which convert respectively into plutonium-239 & plutonium-241.

Obviously fertile and recently fecund. In July 2023 Lindsay Lohan announced the birth of her first child.

Further along the scale are the actinides which demand more than one neutron capture before arriving at an isotope which is both fissile and long-lived enough to capture another neutron and reason fission instead of decaying. These strings include (1) plutonium-242 to americium-243 to curium-244 to curium-245, (2) uranium-236 to neptunium-237 to plutonium-238 to plutonium-239 and (3) americium-241 to curium-242 to curium-243 (or, more likely, curium-242 decays to plutonium-238, which also requires one additional neutron to reach a fissile nuclide). Since these require a total of three or four thermal neutrons eventually to fission, and a thermal neutron fission generates typically only two to three neutrons, these nuclides represent a net loss of neutrons although, in a fast reactor, they may require fewer neutrons to achieve fission, as well as producing more neutrons when they do.

No comments:

Post a Comment