Vernacular (pronounced vuh-nak- yuh-ler (U) or ver-nak-yuh-ler (Non-U))

(1) In linguistics, the dialect of the native or

indigenous people as opposed to that of those (in Western terms) the literary

or learned; the native speech or language of a place; the language of a people or a

national language.

(2) In literature, expressed or written in the

native language of a place, as literary works.

(3) Using, of or related to such language.

(4) Plain, everyday

speech or dialect, including colloquialisms, as opposed to standard, literary,

liturgical, or scientific idiom.

(5) In architecture, a style of architecture

exemplifying the commonest techniques, decorative features, and materials of a

particular historical period, region, or group of people.

(6) Noting or pertaining to the common name for a

plant or animal, as distinguished from its Latin scientific name.

(7) The language or vocabulary peculiar to a

class or profession.

(8) Any medium or mode of expression that

reflects popular taste or indigenous styles.

(9) In linguistic anthropology, language lacking standardization or

a written form.

1599: From the Latin vernāculus (household, domestic,

indigenous, of or pertaining to home-born slaves), a diminutive of verna (a native; a home-born slave (slave

born in the master's household)) although etymologists note the lack of

evidence to support this derivation, verna of Etruscan origin. Now used in

English almost always in the sense of Latin vernacula

vocabula, in reference to language, the noun sense “native speech or language of a place”

dating from 1706. In technical use,

linguistic anthropologists use neo-vernacular and unvernacular while in

medicine, epidemiologists distinguish vernacular diseases (restricted to a

defined group) from those induced by external influences. There are also variations within the

vernacular, concepts like “street vernacular” or “mountain vernacular” used to

differentiate sub-sets of native languages, based on geography or some

demographic; in this the idea is similar to expressions like jargon, argot,

dialect or slang. Vernacular is a noun

& adjective, vernacularism & vernacularist are nouns and vernacularly

is an adverb; the noun

plural is vernaculars.

Cannabis (known also as marijuana) is a psychoactive drug from the cannabis plant (Cannabis sativa, Cannabis indica, Cannabis ruderalis). In the vernacular it's "weed" or any one of literally hundreds of other terms.

Vernacular and other Latin

In the intricate world of linguistics, there are many types of Latin, many of them technical differentiations between the historic later variations (Medieval Latin; New Latin, Enlightenment Latin) from what is (a little misleadingly) called Classical Latin (or just “Latin”) but there was also a Latin vernacular referred to as vulgar Latin, one of many forks:

Vulgar Latin (also as popular Latin or colloquial Latin) was the spectrum of non-formal registers of Latin spoken from the Late Roman Republic onward and the what over centuries evolved into a number of Romance languages. It was the common speech of the ancient Romans, which is distinguished from standard literary Latin and is the ancestor of the Romance languages.

Dog Latin (also as bog Latin (ie “toilet humor”)): Bad, erroneous pseudo-Latin, often amusing constructions designed to resemble the appearance and especially the sound of Latin, many of which were coined by students in English schools & universities. The “joke names” used in Monty Python's Life of Brian (1979) (Sillius Soddus, Biggus Dickus & Nortius Maximus) are examples of dog Latin.

Pig Latin: A type of wordplay in which (English) words are altered by moving the leading phonetic of a word to the end and appending -ay, except when the word begins with a vowel, in which case "-way" is suffixed with no leading phonetic change.

Apothecary's Latin: Latin as it was supposed spoken by a barbarian, reflecting the (probably not wholly unjustified) prejudices of the educated at the pretentions of tradesmen and shopkeepers.

Legal Latin: Latin phrases or terms used as a shorthand encapsulation of legal doctrines, rules, precepts and concepts).

Medical Latin: This evolved into a (more or less) standardized list of medical abbreviations, based on the Latin originals and used as a specific technical shorthand.

Barracks Latin: (pseudo Latin on the lines of dog Latin but usually with some military flavor, often noted for a tendency to vulgarity).

Ecclesiastical Latin: (also as Church Latin or Liturgical Latin), a fork of Latin developed in late Antiquity to suit the particular discussions of Christianity and still used in Christian liturgy, theology, and church administration (events in 2013 confirming that papal resignations are written and delivered in ecclesiastical Latin). Technically, it’s a fork of Classical Latin but includes words from Vulgar & Medieval Latin as well as from Greek and Hebrew, sometimes re-purposed with meanings specific to Christianity (and sometimes just the Church of Rome).

The idea of the difference is best remembered in the example of the Vulgate Bible, the Latin translation of the Bible from Hebrew and Greek made by Saint Jerome (circa 345-420), the details of his interpretations (which tended to favor the role of the institutional church rather than the personal relationship between Christ and individual Christian) for centuries the source of squabble schism. Vulgate was from the Latin vulgāta, feminine singular of vulgātus (broadcast, published, having been made known among the people; made common; prostituted, having been made common), perfect passive participle of vulgō (broadcast, make known). When after the conclusion of the Second Vatican Council (Vatican II; 1962-1965), it was decided to permit the celebration of the mass in local languages rather than ecclesiastical Latin, such use was said to be “in the vernacular”.

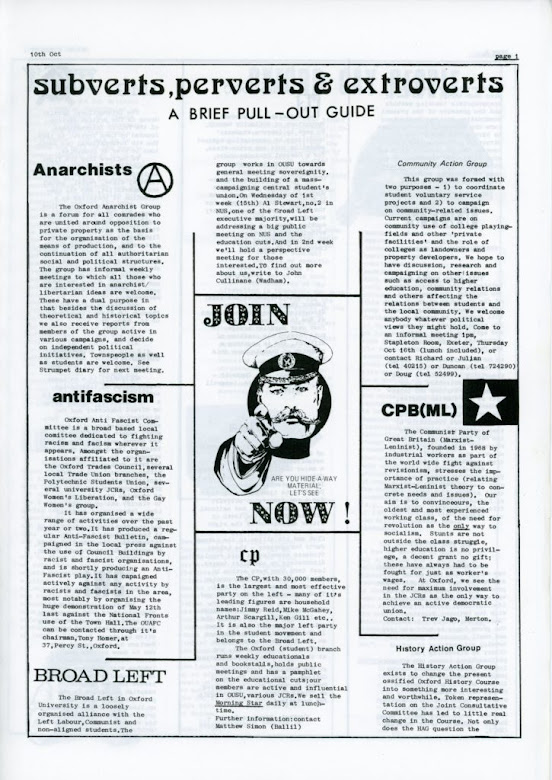

Under the Raj: three marquises, three viceroys; Lords Lytton (left), Rippon (centre) and Lansdowne (right). Upon leaving office, UK prime-ministers were usually granted an earldom but viceroys of India were created Marquises, a notch higher in the peerage.

Under the Raj, there were many vernacular languages; indeed, never did the colonial administrators determine just how many existed, all the fascinated dons giving up after counting hundreds and finding yet more existed. One difficulty this did present was that it was hard to monitor (and if need be censor) all the criticism which might appear in non-English language publications and, because at the core of the British Empire was racism, violence and rapacious theft of other peoples’ lands and wealth, criticism was not uncommon. In an attempt to suppress these undercurrents of dissatisfaction, the viceroy (Lord Lytton, 1831–1891; Viceroy of India 1876-1880) imposed the Vernacular Press Act (1878), modelled on earlier Irish legislation, the origins of the word in the Latin verna (a slave born in the master's household) not lost on Western-educated Indians. Not content with mere suppression, Lord Lytton also created an operation to feed to the press what he wanted printed, using bribery where required. Fake news was soon a part of these feeds and some historians have suggested the act probably stimulated more resentment than it contained. In 1881, Lytton’s successor (Lord Rippon, 1827–1909; Viceroy of India 1880-1884) withdrew the act but the damage was done. The legislative reforms of the viceroys of India varied in intent and consequence. Lord Lansdowne (1845–1927; Viceroy of India 1888-1894) enacted the Age of Consent Act (1891), raising the age of consent for sexual intercourse for girls (married or unmarried), from ten to twelve, any violation an offence of statutory rape. Those who like to defend what they claim was the civilizing mission of empire sometimes like to cite this but seem never to dwell on the marriage age for girls in England being twelve as late as 1929.