Proboscis (pronounced proh-bos-is

or proh-bos–kis)

(1) A

long flexible prehensile trunk or snout, as that of an elephant.

(2) In zoology,

any elongated tube from the head or connected to the mouth.

(3) In entomology

& malacology, the elongate, protruding mouth parts of certain insects and certain

invertebrates like insects, worms and molluscs, adapted for sucking or piercing

(more popularly called “the beak”).

(4) Any

of various elongate feeding, defensive, or sensory organs of the oral region,

as in certain leeches and worms.

(5) In

facetious use, the human nose, the use probably roughly with the size of

prominence of the nose.

(6) In

informal use, as applied in geography, engineering, geometry etc, any

protrusion vaguely analogous with the human nose.

1570-1580:

From the Latin proboscis (trunk of an

elephant), from the Ancient Greek προβοσκίς (proboskís) (elephant's trunk (literally “feeder; means for taking

food"), the construct being προ- (pro-)

(before) + βόσκω

(bóskō) (to nourish, to feed”), from boskesthai (graze, be fed), from the

stem bot- (source of botane (grass, fodder) and from which

English gained botanic), from the primitive Indo-European root gwehs (source also of βοτάνη (botánē) (grass, fodder) + -is (the noun suffix). The related terms include nose beak, organ,

snoot, snout, trunk and probably dozens of slang forms. Other descendents from the Latin include the Italian

proboscide, the Portuguese probóscide and the Spanish probóscide. Proboscis & proboscidean are nouns and proboscidate

is an adjective; the noun plural is proboscises or proboscides. The Greek derived form of the plural (proboscides)

appears often in the technical literature that built using the conventions of

English (proboscises) appears to be the common general form, rare though it is.

#Freckles:

Lindsay Lohan’s nose.

Aerodynamics were

of interest to some even in the early days of the automobile and those involved

in motorsport were more interested than most.

For decades, the interest manifested mostly in the art of

streamlining, the reduction of drag and research, accomplished mostly without

wind-tunnel testing and obviously without computers, tended to produce

cigar-shaped bodies with as few protrusions as possible. Drag in many cases was certainly minimized,

some of the shapes rendered in the 1920s & 1930s delivering drag

coefficients (CD) impressive even by twenty-first century standards but it took

a long time before fully it was understood that the fluid dynamics (the

behavior of air) at the rear of a vehicle could be as significant as the more

obvious disturbances at the front. Not

un-related to this was that it also took time (and not a few deaths) before it

was appreciated quite how vital was the trade-off between drag-reduction and

the downforce needed to ensure cars did not “take-off” from the surface, resulting

in instant instability.

The 1923

Benz Tropfenwagen (teardrop vehicle) (left) not only used an aerodynamic nose

using lessons learned from military aviation during World War I (1614-1918) but

was able to optimize the shape because the engine was mid-mounted, something

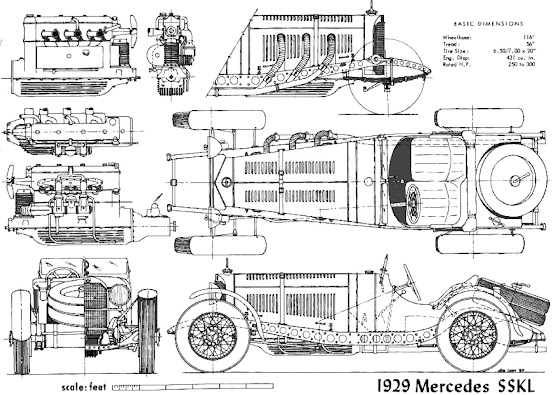

would wouldn’t become commonplace in Formula One for over thirty years. The front-engined 1931 Mercedes-Benz

SSKL (centre) made few concessions to aerodynamics, relying on sheer power and

weight-trimming to win the 1931 German Grand Prix but even by then it was clear the approach had reached its evolutionary dead-end. Time and the competition had definitely caught up by 1932 however and it was no longer possible further to lighten the chassis or increase power so the factory had aerodynamics specialist Baron Reinhard von Koenig-Fachsenfeld (1899-1992) design a streamlined body (right), the lines influenced by wartime aeronautical experience. This coaxed from the SSKL, one last successful season. Crafted in aluminum by Vetter in Cannstatt, it was mounted on Manfred von Brauchitsch's (1905-2003) race-car and proved its worth at the at the Avus race in May 1932; with drag reduced by a quarter, the top speed increased by over 12 mph (20 km/h) and the SSKL won its last major trophy on the unique circuit which rewarded straight-line speed like no other. It was the last of the breed. Subsequent grand prix cars would be pure racing machines with none of the compromises demanded for road-use.

That

the early attempts at streamlining might induce aircraft-like “take-offs” was

not surprising given so much of the available data came from work in ballistics

and aeronautics where lift is desirable and as speeds rose, it became clear

what would need also to be considered was what air was doing underneath the

vehicle, some cars obviously with "just enough lift to be a bad airplane" as one driver put it. That increase in speed in itself imposed a limit on research, the terminal velocities suddenly possible

exceeding the capacity of ground-effects based wind tunnels and few

manufacturers had access to test facilities with straights of sufficient length

to match those on some race-tracks.

High-speed testing was thus sometimes undertaken by racing drivers at

speeds rarely before explored, something complicated by being among disrupted

air induced by surrounding cars and some unpredictable behavior ensued; it was actually remarkable there weren’t more fatalities than there were.

2020 Jaguar C-Type (XK120-C) (2014 continuation of 1953 production, left) & 1957 Jaguar XKSS (right).

In the

embryonic study of aerodynamics, one of the first conclusions (correctly) drawn

was that few changes produced more dramatic improvements than lowering and

optimizing the shape of the nose. At the

time, it was something not as simple as it sounded, engines mounted usually

close to the nose and in the era, those usually long-stroke engines were tall,

often in-line units, a shape which imposed limits on what was possible. Jaguar used dry-sump lubrication on the

D-Type (and the road-going derivative the XKSS) to allow the nose to drop a few

inches compared with its predecessor, an expedient also adopted by Mercedes-Benz

for their 300 SL (W198, 1954-1963) and 300 SLR (W196S, 1955), more lowering

still made possible by mounting the power-plant on a slant.

1954

Maserati 250F with the original “short nose” body and 1956 (centre) and 1957

(right) variations of the “long nose”.

In the

same era, Maserati, impressed by the speed of the Mercedes-Benz W196 when

fitted with the "streamliner" body used on the faster circuits and, apparently

without the benefit of a wind-tunnel, developed its own partially enclosed

bodywork for its 250F Grand Prix car but it also developed, quite serendipitously,

an even more effective shape and it was initially known as the “long-nose”

250F until it proved so successful it was adopted as the definitive 250F body. The 1957 “long nose” 250F (right) is the one with which Juan Manuel Fangio, won the German Grand Prix at the Nürburgring in August, 1957, an epic drive and his most famous. Fangio was Scuderia Alfieri Maserati’s team leader and a splash of yellow was added to the nosecone of his 250F so easily it could be identified, the color chosen because it was one of the two allocated to his native Argentina. The 250Fs of the other team members also had nosecones painted in accordance with the original international auto racing colours standardized early in the century, American Harry Schell (1921–1960) in white and Frenchman Jean Behra (1921–1959), blue, all atop the factory’s traditional Italian red.

The

long and short of it: The Ferrari 250 LM in long (left) and short (right) nose

configuration.

Ferrari

and others noted the gains aerodynamics provided and among engineers, some

fairly inaccurate (though broadly indicative) "rules of thumb" emerged, based

usually on the calculation that for every one inch (25 mm) reduction in nose

height, an effective gain of so many horsepower would be realized. Precise or not, the method, honed by

slide-rules, lingered until computer calculations and wind tunnels began more

accurately to produce the numbers. Ferrari’s

first mid-engined sports car, the 250 LM (1963-1965), was one of the vehicles

to benefit from a nose job, the revised bodywork fashioned by coachbuilder

Piero Drogo (1926–1973) who had formed the Modena-based Carrozzeria Sports Cars

to service the ecosystem of sports cars that congregated in the region. There was an urban myth the Drogo nose was

created so an “FIA standard size” suitcase could be carried (to convince the

regulatory body it was a car for road and track rather than a pure racing

machine) but it was really was purely for aerodynamic advantage.

Ferrari

250 LM, the short-nose chassis 6321 (left) and the long-nose (5893) right.

Testing

confirmed the “Drogo nose” certainly conferred aerodynamic benefits on the 250 LM

but the change brought it own difficulties because Ferrari was at the time attempting

to convince the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (the FIA; the

International Automobile Federation and international sport's dopiest regulatory body) the 250 LM should be homologated in the

Grand Turismo (GT) category so it could contest the World Sports Car

Championship. This was being done using

the argument the 250 LM was a mere update of the 250 GTO, despite the 250 LM having a different engine & transmission (mid rather than front-mounted)

and a different body. For homologation

to be granted, there had to be 100 essentially identical examples of the model

produced and given (1) there were such fundamental differences from the earlier

250s and (2) not even two dozen 250 LMs had then been produced, the FIA was understandably

reticent. Anticipating the FIA would (as usual) find some rationalization to accommodate Ferrari's demand, the factory issued a very

public recall notice for all 250 LMs to be returned to Maranello to be fitted

with the Drogo nose. One 250 LM (chassis

6321) however was by then being raced in Australia which was a long way away so

that one was quietly overlooked (the FIA either turned a blind eye or didn't check), meaning that at least for some time it was the

only “short-nosed” 250 LM left in the world, although it’s known at least two have since

been restored back to their original specification. Now resident mostly in collections or museums with occasional trips to the auction house, high-speed stability is no longer always critical. Eventually, 32 250 LMs would be built and the

FIA didn’t relent, forcing the car to compete in the 1965 championship against

much faster machinery in the prototype class but it was fast enough and

importantly, more reliable than the more fragile prototypes and chassis 5893

won the 1965 Le Mans 24 hour endurance race, Ferrari's last victory in the event until the "threepeat" in 2023-2024-2025. In February 2025, at RM Sotheby's Paris Auction, the Scaglietti-bodied 1964 250 LM which won at Le Mans in 1965 (and the only Ferrari from the era to compete in six 24 hour races) was sold for US$36.2 million. The car had for decades been on display at Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum, like the 1954 Mercedes-Benz W196R Stromlinienwagen (streamliner) which a few days earlier had fetched US$53 million.

1965

Ferrari 250 LM Stradale by Carrozzeria Pininfarina (Chassis 6025 LM in the “long nose”

style with the “Drogo nose”). The two seats, electric windows and lashings of red vinyl (some quilted) papered over the cracks between road and race cars but while the longer wheelbase made thing less cramped, the origin as something designed for one to use in competition was obvious in the size of the footwells where four feet would have to fit a space designed for two. Although

quintessentially Italian, most 250 LMs were made in right-hand drive (RHD) configuration

because they were intended for use on circuits where that conferred some advantage,

the tradition of anti-clockwise racing meaning a majority of turns were right

and the RHD layout afforded drivers a better view.

Denied homologation and thus buyers from teams wanting what would have been the fastest Group 3 GT available, Ferrari decided to test the market of the rich, displaying the the 250 LM Stradale (Road), complete with a (slightly) more civilized interior and electric windows. A

genuine attempt at something derived from a racing car (in the manner of the

1968 Ford GT40 Mark III) rather than merely a racing car with mufflers (like

the road-registrable Mark I GT40s or the 1955 Mercedes-Benz Uhlenhaut Coupés), the Stradale (chassis 6025 LM) used a

lengthened version of the Tipo 577 tubular steel chassis with the wheelbase

extended from 2400 to 2600mm (94-102 inches), providing a more generously sized

passenger compartment. Unlike the rest

of the 250 LM line for which the bodies which were fabricated by Scaglietti in

Modena, the LWB (long wheelbase) coachwork was created by Pininfarina at their

Grugliasco facility. Millionaires in the US identified as potentially the most receptive (and lucrative) market, the Stradale was painted in the white and blue then used by many American teams and presented at the 1965 Geneva Salon. Unfortunately, it transpired the buyers for raucous racing cars and those for boulevard cruisers inhabited two different planets and no orders were received so the Stradale remained an exquisite one-off although the factory did later convert chassis 5995 LM to quasi Stradale specification (on the standard wheelbase) and even fitted air-conditioning.

Ferrari

275 GTB (1964-1968): A 1964 "short nose" (left) and a "long-nose" (right), the latter designated Series II which debuted in 1966. The 14×6.5″

Campagnolo magnesium-alloy wheels (part number 40366) are known colloquially as the "starbursts".

The

1960s saw the last generation of Ferrari cars styled without the use of wind

tunnels or much in the way of electronic assistance. Even for the road cars, as speeds rose, some

high speed instability was occasionally noted but this became pronounced with

the cars were used in competition, especially on the faster tracks with the

long straights. Accordingly, knowing

there would be a competition version of the 275 GTB (the 275 GTB/C) a long-nose

was created which was also used on other models beginning in 1966. The 275 GTB/C was notable also for marking

the swan song of the classic Borrani wire-spooked wheels on Ferrari competition

cars, the elegant, chromed creations no longer strong enough to handle the

increase loads in extreme conditions now that tyres provided much more adhesion; they were replaced by aluminium or magnesium-alloy castings.

1964 Ferrari 275 GTB/C Berlinetta Competizione (short nose) with competition specification 15" Borrani wire wheels.

By

1966, standard equipment on the 275 GTB/4 were 7.0 x 14" Campagnola

magnesium-alloy wheels. The 7.0 x

14" Borrani wire wheels (RW4039) were a special-order option and the

competition specification 7.0 x 15” Borrani wire wheels (RW4010) fitted to the

front of 275 GTB/C could also be ordered.

The 7.5 x 15" Borrani wire wheels (RW4011) were exclusive to the

275 GTB/C on which they were fitted to the rear. The competition specification wheels varied

in construction in that the front units had the spokes laced to the outer bead

seat while those of the rear were centrally laced. The difference in construction represented

the different loadings each would have to endure in extreme use, the stresses

at the rear quite different since the introduction of independent rear

suspension. Having to cease use of the

classic wire wheels because the grip of modern racing tyres produced loadings

which physically cracked the spokes brought problems with brake cooling,

addressed with the new design of five spoke wheel fitted to the 365 GTB/4

Daytona although, on the road cars, the Borrani wire wheels remained available.

1969 Dodge Daytona (left) and 1968 Dodge Charger 500 (right).

Across

the Atlantic, on the NASCAR (National Association of Stock Car Auto Racing)

circuits, the manufacturers had reached a dead end imposed by their regulatory

body. By 1969 the NASCAR authorities had

fine-tuned their rules, restricting engine power and mandating a minimum weight

so manufacturers, finding it increasingly harder to cheat, resorted to the then

less policed field of aerodynamics, ushering what came to be known as the brief era of the "aero-cars". Dodge began by making modifications

to their Charger which smoothed the air-flow, labelling it the Charger 500 in a

nod to the rules which demanded 500 identical models for eligibility. It proved less successful than hoped and

Dodge apparently gave up on the design, producing only 392 (although to make up

the numbers they did the next year add an unrelated “500” option to the Charger line and NASCAR generously turned their blind eye).

Not discouraged however, Dodge recruited engineers from Chrysler's soon

to be shuttered (as arms control treaties with the USSR loomed) aerospace &

missile division and quickly created the Daytona, adding to the 500 a

protruding nosecone and high wing at the rear.

Even now, the nosecone would be thought extreme but it worked on the

track and this time the required 500 were actually built. NASCAR responded by again moving the

goalposts, requiring manufacturers to build at least one example of each

vehicle for each of their dealers before homologation would be granted,

something which would demand thousands of cars.

Accepting the challenge, in 1970 Dodge's corporate stablemate Plymouth duly built about two-thousand of

their similar aero car, the Road Runner Superbird, an expensive exercise given

they reportedly lost money on each one.

Now more unhappy than ever, NASCAR lawyered-up, drafted rules rendering

the aero-cars uncompetitive and their brief era ended. So extreme in appearance were the cars they

proved at the time sometimes hard to sell and some were actually converted back

to the standard specification to get them out of the showroom. Views changed over time and they're now much

sought by collectors, selling for up to US$3 million in the most desirable

configuration.

1969 Ford

Torino Sportsroof (left) 1969 Ford Torino Talladega (right).

As imposing

as the noses developed for the Daytona and Superbird were, it may have been that

much of the modification was wasted effort and an application of the Europeans’

old “inch by inch” rule of thumb might have been as effective. The nose jobs Ford in 1969 applied to their Torino

Talladega and Mercury’s Cyclone Spoiler II were modest compared to what

Chrysler did. The grill was flattened, a

la the Charger 500, the front bumper was replaced with a re-shaped version of

the rear unit from a 1969 Fairlane which functioned effectively as an air-dam

and the leading edge of the nose was extended and re-shaped downwards. The effect was subtle but on the track,

appeared to confer a similar advantage to the one Chrysler’s rocket scientists

had achieved but Ford had also made some changes which lowered the centre of

gravity and improved the under-body air-flow.

Quite what this achieved has never been documented but the drivers were certainly

convinced, retaining the Talladegas and Cyclone Spoilers as long as possible,

the shapes proving much more efficient than their sleek-looking successors.

Porsche

911 (930) Turbo in profile (left) and Porsche 911 (930) flachbau (slantnose).

When in 1973 regulations forced Porsche to fit more substantial bumpers to the 911 (in production since 1964), it necessitated a change to the front bodywork, the earlier cars became known as the "long hood" and subsequent models the "short hood", both references to the hood (bonnet) being shortened to accommodate the unsightly battering rams. More nose jobs would follow. Between

1982-1989, Porsche produced three generations of the 911 (930) Turbo S with the

flachbau (slantnose) bodywork, a

total of 948 believed built. It seems

there were a few, hand-built prototypes completed by 1980 in addition to one

completed under the factory’s Sonderwunsch

(special wishes) programme for an individual who was either well-connected or a

very good customer. The 58 first generation

cars lack the pop-up headlamps so associated with the design, instead using smooth,

flat-faced wings with a fibreglass front valance assembly containing twin lamps

either side below the bumper. Nicknamed

the “hammerhead”, the styling divided opinion and was anyway found not to be

compliant with regulations in some markets, thus the substitution of the pop-up

headlamps which appeared during 1983. As

was typical of much which emerged from the programme, the cars were built with

a variety of Sonderwunsch options so there was no one consistent

specification.

1973 Porsche 911 Carrera RS from the long hood era (1963-1973, left) and 1975 Porsche 911 Turbo (930) with the short hood (used between 1973-1989, (right). Such is the lure of the early 911s something of a cottage industry has emerged, devoted to "backdating" later cars. The change in 1974 was necessitated by US "front impact" laws which emerged from lobbying by the insurance industry which wished to avoid liability for "low speed" accidents such as those associated typically with supermarket car parks. Later, the technology improved and the laws were revised but until the 1990s, bumper bars described as "battering rams" or "railway sleepers" were a common sight on US market cars and because of the economics of production, some manufacturers were compelled to inflict them also on the RoW (rest of the world) cars.

The second

generation flachbau yielded 204 cars,

the styling updated with a simplified air dam containing driving lights and a

centrally mounted oil-cooler, the pop-up headlamps relocated to front wings, a

much admired feature the optional air-intake vents above the pop-ups, something

borrowed from the 935 track cars. Again, other than the structural changes,

there was no standard configuration, each flachbau

reflecting the buyer’s ticking of the option list and any special wishes the

factory was able to satisfy. The third

generation were the most numerous with 686 produced, the increased volume reflecting

the effort made to ensure the cars could be made available in the lucrative US market which eventually received 630 flachbaus. More standardized, production shifted from

the Sonderwunsch’s Restoration and

Repair Department facility (Werks 1)

to the line in Zuffenhausen where the standard 930s were assembled though for ease of completion (and to maintain exclusivity)

the cars were transferred to the Sonderwunsch

for finishing and detailing.

Mercedes-Benz Heckflosse: Top row W112s:

1964 300 SE (left) and 300 SE Lang (long) (right); Bottom row W111s: 1967 230

(left) and 1967 230 S (right). Although

both 230s used the 2.3 litre straight-six, the basic 230 used the “short nose”

front from the four-cylinder W110 while the more expensive 230 S was fitted

with the “long nose” from the W111 & W112.

All W112

models (sedan (1961-1965), coupé & cabriolet (1962-1967)) were designated

300 SE including the LWB (long wheelbase) “Lang” models with the extended rear

doors (on a wheelbase of 2850 mm (112.2 inches) against the 2750 mm (108.27

inches) of the standard 300 SE. It

wasn’t until the debut of W109 range (1965-1972) the SEL designation was

adopted for the LWB sedans and that would persist until 1993 when the corporate

alpha-numeric text strings were re-configured.

The 1964 300 SE Lang pictured above (one of 1,546 LWBs) was built as a

factory exhibition car (code 997) for that year’s European show circuit and

featured the rarely ordered electric partition (code 214). After the show season, the car was sold to the

royal household of the Netherlands before being passed to the Ministry of

Foreign Affairs which allocated it to the Embassy in Belgium.

1965 Mercedes-Benz 190

(W110).

The difference in wheelbase between the W111 & W112 is well-known

but in 1961 the W110 range was introduced, comprising a range of four-cylinder

gas (petrol) and diesel models and these used the W111/W112 body fitted with a

shorter nose. That of course made sense

because an in-line four is shorter than an in-line six. However, when the six cylinder W111 (220, 220

S & 220 SE) sedans were in 1965 replaced by the W108 & W109, the W110

remained in production until 1968 along with the newly created 230 & 230 S,

the latter pair using the new 2.3 litre six, the former in the “short nose”

W110 body while the better appointed, more expensive 230 S used the “long nose”

coachwork. The short & long noses

thus came to signify a place in the hierarchy rather than the number of

cylinders under the hood (bonnet). This

had years earlier been done by some US manufacturers which until the 1950s offered

some models with straight-sixes and more expensive ones with straight-eights,

the latter with a longer nose better to accommodate the longer engine. However, when the industry shifted from

straight-eights to V8s, the manufacturers didn’t take advantage of the new

configuration being shorter by using shorter noses than those used for the

on-going sixes, instead, in some cases, the V8s still got “long nose”

coachwork, resulting in much un-used under-hood space and the fitting of

enveloping “fan shrouds” to ensure cooling of the now more distant V8 engines.

Wax

model of Thomas Wedders (circa 1730-circa 1782).

Thomas Wedders (AKA Thomas Wadhouse) from

Yorkshire, England (a member of a travelling "freak show" circus) is

recorded as having enjoyed (sic) the world's longest known human nose, claimed to

be some 200mm (7¾ inches) in length. In

the absence of any verified evidence, the truth of that can't be known but it

may be assumed his nose was very big.

The current record is held by Mehmet Özyürek (b 1949) of Türkiye, his

nose officially measured and found to be 88mm (3½ inches).

The

political proboscis: Crooked Hillary Clinton (b 1947; US secretary of state

2009-2013, left), Julia Gillard (b 1961; Australian prime minister 2010-2013,

centre) and Donald Trump (b 1946; US president 2017-2021 and since 2025,

right). In case uncultured Australians didn't get

the "Pinocchio" connection and its implication, some phonetically

opportunistic critics also labeled Julia Gillard “Juliar”. Note the hammer & sickle appended to crooked Hillary, more evidence she was the victim of a “vast right-wing conspiracy”.

The

fictional Pinocchio was the protagonist in the children's tale The Adventures of Pinocchio (1883) by

Italian writer Carlo Collodi (1826-1890).

Carved from timber by a Tuscan woodcarver, he is best known for his nose;

it grows as he tells lies. As a motif it has

proved irresistible for cartoonists and meme-makers depicting politicians, a

breed notorious for their distant and infrequent relationship with

truthfulness. Remarkably, Jimmy Carter

(b 1924; US President 1977-1981) seems not to have been drawn with a nose-job suggesting mendacity. Although there was some cynicism when, during

his successful 1976 presidential campaign he asserted: “I'll never tell a lie”, that did

have some resonance in a electorate which had been scandalized by the

revelations from Richard Nixon's (1913-1994; US president 1969-1974)

administration and although judged a failure, there's nothing in the record to

suggest Carter ever was untruthful about anything substantive. That may not be unique among politicians but

it’s untypical.