Scoop (pronounced skoop)

(1) A ladle or ladle-like utensil, especially a small,

deep-sided shovel with a short, horizontal handle, for taking up flour, sugar

etc.

(2) A utensil composed of a palm-sized hollow hemisphere

attached to a horizontal handle, for dishing out ice cream or other soft foods.

(3) A hemispherical portion of food as dished out by such

a utensil.

(4) The bucket of a dredge, steam shovel etc.

(5) In medicine, a spoon-like surgical apparatus for

removing substances or foreign objects from the body; a special spinal board

used by emergency department staff that divides laterally (ie literally “scooping

up” patients).

(6) A hollow or hollowed-out place.

(7) The act of ladling, dipping, dredging etc.

(8) The quantity held in a ladle, dipper, shovel, bucket

etc.

(9) In journalism, a news item, report, or story revealed

in one paper, magazine, newscast etc before any other outlet; in informal use, news,

information, or details, especially as obtained from experience or an immediate

source.

(10) A gathering to oneself, indicated usually by a

sweeping motions of the hands or arms.

(11) In informal use, a big haul of something.

(12) In television & film production, a single-lens

large floodlight shaped like a flour scoop and fitted with a reflector.

(13) To win a prize, award, or large amount of money.

(14) In bat & ball sports, to hit the ball on its

underside so that it rises into the air.

(15) In hydrological management, a part of a drain used to

direct flow.

(16) In air-induction management (to the engines in cars,

boats, aircraft etc), a device which captures external the air-flow and directs

it for purposes of cooling or combustion.

(17) In Scots English, the peak of a cap.

(18) In pinball, a hole on the playfield that catches a

ball, but eventually returns it to play in one way or another.

(19) In surfboard design, the raised end of a board.

(20) In music (often as “scoop up”), to begin a vocal

note slightly below the target pitch and then to slide up to the target pitch, prevalent

particularly in country & western music.

1300–1350: From the Middle English scope & schoupe, from

the Middle Dutch scoep, scuep, schope & schoepe (bucket for bailing water) and the Middle Dutch schoppe, scoppe & schuppe (a

scoop, shovel (the modern Dutch being schop

(spade)), from the Proto-Germanic skuppǭ & skuppijǭ, from the primitive Indo-European kep & skep- (to cut,

to scrape, to hack). It was cognate with

the Old Frisian skuppe

(shovel), the Middle Low German schōpe

(scoop, shovel), the German Low German Schüppe

& Schüpp (shovel), the German Schüppe & Schippe (shovel, spade) and related to the Dutch schoep (vessel for baling). The mid-fourteenth century Middle English verb

scōpen (to bail out, draw out with a

scoop) was from the noun and was from the Middle Low German schüppen (to draw water), from the Middle

Dutch schoppen, from the Proto-Germanic

skuppon (source also of the Old Saxon

skeppian, the Dutch scheppen, the Old High German scaphan and the German schöpfen (to scoop, ladle out), from the

primitive Indo-European root skeubh-

(source also of the Old English sceofl (shovel)

and the Old Saxon skufla.

Sherman L Kelly's (1869–1952) ice-cream scoop (the

dipper; 1935) was a masterpiece of modern industrial design and thought sufficiently aesthetically

pleasing to be a permanent exhibit in New York's Museum of Modern Art

(MoMA). Its most clever feature was the fluid encased in the handle; being made from cast aluminum, the heat

from the user's hands was transferred to the cup, obviating the need for the

moving parts sometimes used to separate the ice-cream for dishing out. The dipper is like the pencil, one of those designs which really can't be improved.

The meaning “hand-shovel with a short handle and a deep,

hollow receptacle” dates from the late fifteenth century while the extended

sense of “an instrument for gouging out a piece” emerged by 1706 while the colloquial

use to mean “a big haul” was from 1893. The

journalistic sense of “the securing and publication of exclusive information in

advance of a rival” was an invention of US English, first used in 1874 in the

newspaper business, echoing the earlier commercial verbal slang which imparted

the sense of “appropriate so as to exclude competitors”, the use recorded in

1850 but thought to be considerably older.

The meaning "remove soft or loose material with a concave

instrument" dates from the early seventeenth century while sense of “action

of scooping” was from 1742; that of “amount in a scoop” being from 1832. The noun scooper (one who scoops) was first used

in the 1660s and the word was adopted early in the nineteenth century to

describe “a tool for scooping, especially one used by wood-engravers”, the form

the agent noun from the verb scoop. Scoop

is a noun & verb, scooper & scoopful are nouns and scooped &

scooping are verbs; the noun plural is scoops.

XPLR//Create’s fluid dynamics tests comparing the

relative efficiency of ducts (left) & scoops (right).

In air-induction management (to the engines in cars,

boats, aircraft etc), a scoop is a device which captures external the air-flow

and directs it for purposes of cooling or combustion. An air scoop differs from an air duct in that

a scoop stands proud of a structure's surface allowing air to be

"rammed" into its ducting while a duct is an aperture integrated into

the structure, "sucking" air in from the low pressure zone created by

its geometry. For a given size of aperture,

a scoop can achieve an airflow up to twice that of a duct but that doesn't of

necessity mean as scoop is always preferable, the choice depending on the

application. In situations where optimal

aerodynamic efficiency is desired, a duct may be chosen because scoops can

increase frontal area and almost always, regardless of placement, leave a wake of

turbulent air, further increasing drag.

It's thus one of those trade-offs with which engineers are familiar: If

a scoop is used then sufficient air is available for purposes of cooling &

combustion but at the cost of aerodynamic efficiency while if a duct is fitted,

drag is reduced but the internal air-flow might be inadequate.

NACA Ducts: 1969 Ford Shelby Mustang GT500 (left), 1971

Ford Mustang Mach 1 351 (centre) & 1972 Ford Falcon GTHO Phase IV (Right).

When Ford introduced NACA ducts on the 1971 Mustangs (subsequently

adopted by Ford Australia in 1973 for the XB Falcon), whether in error or to

take advantage of the public’s greater “brand-awareness” of the National

Aeronautics & Space Administration (NASA), they were promoted as “NASA ducts”. In fairness, the two institutions were

related, NASA created in 1958 after the National Advisory Committee for

Aeronautics (NACA) was dissolved, the process essentially a name change

although much had changed since the NACA’s formation in 1915, the annual budget

then US$5000 and the dozen committee members unpaid. The NACA duct was one of many innovations the

institution provided to commercial and military aviation and in the post-war

years race cars began to appear with them, positioned variously to channel air to

radiators, brakes and fuel induction systems as required.

Scoops: 1969 Ford Mustang Boss 429 (left), 1969 Ford

Mustang Mach 1 428 CobraJet (with shaker scoop) (centre) & 1974 Pontiac

Trans Am 455 SD (with rearward-facing scoop) (right).

From those pragmatic purposes, the ducts migrated to road

cars where often they were hardly a necessity and, in some cases, merely

decorative, no plumbing sitting behind what was actually a fake aperture. Scoops appeared too, some appearing extravagantly

large but there were applications where the volume of air required was so high

that a NACA duct which would provide for the flow simply couldn’t be fashioned. That said, on road cars, there were always suspicions

that some scoops might be fashionably rather than functionally large, the lines

drawn in the styling and not the engineering office. There was innovation in scoops too, some

rearward facing to take advantage of the inherently cool, low pressure air

which accumulated in the cowl area at the base of the windscreen although the

best remembered scoops are probably the “shakers”, assemblies protruding

through a hole in the hood (bonnet) and attached directly to the air-cleaner

which sat atop the carburetor, an arrangement which shook as the engine

vibrated. By such things, men are much amused.

The inaugural meeting of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), 23 April 1915.

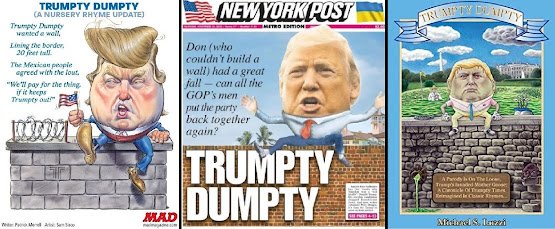

A New York Post scoop, 29 June 2007. This was the Murdoch press's biggest scoop

since the publication in 1983 of the "Hitler Diaries". The "diaries" turned out to be forgeries; the picture of

Lindsay Lohan resting in a Cadillac was genuine.