Muffler (pronounced muhf-ler)

(1) A

scarf worn around one's neck for warmth.

(2) Any

of various devices for deadening the sound (especially the tubular device

containing baffle plates in the exhaust system of a motor vehicle) of escaping

gases of an internal-combustion engine; also known as silencers.

(3) Anything

used for muffling sound.

(4) In

armor, a mitten-like glove worn with a mail hauberk.

(5) A

boxing glove (archaic).

(6) A slang

term for a kiln or furnace, often electric, with no direct flames (technically a

muffle furnace)

(7) A

piece of warm clothing for the hands.

(8) The

bare end of the nose between the nostrils, especially in ruminants.

(9) A

machine with two pulleys to hoist load by spinning wheels, a polyspast (from the Latin polyspaston (hoisting-tackle with many pulleys), from the Ancient Greek πολύσπαστον (polúspaston) (compound pulley); a block and

tackle.

(10) In World War I (1914-1918) soldier's slang, a gas-mask (some listings of military slang note it a "rare").

(11) An alternative term for the silencer (or suppressor) sometimes fitted to a gun (usually illicitly).

1525–1535: A compound word, the construct being muffl(e) + -er. Muffle was from the Middle English muflen (to muffle), an aphetic alteration of the Anglo-Norman amoufler, from the Old French enmoufler (to wrap up, muffle), from moufle (mitten), from the Medieval Latin muffula (a muff), of Germanic origin (first recorded in the Capitulary of Aachen in 817 AD), from the Frankish muffël (a muff, wrap, envelope) from mauwa (sleeve, wrap) (from the Proto-Germanic mawwō (sleeve)) + vël (skin, hide) (from the Proto-Germanic fellą (skin, film, fleece)). An alternate etymology traces the Medieval Latin word to the Frankish molfell (soft garment made of hide) from mol (softened, worn), (akin to the Old High German molawēn (to soften)) and the Middle High German molwic (soft), (mulch in English) + fell (hide, skin). The suffix –er was from the Middle English –er & -ere, from the Old English -ere (agent suffix), from the Proto-Germanic -ārijaz (agent suffix). Usually thought to have been borrowed from Latin –ārius, it was cognate with the Dutch -er and -aar, the Low German -er, the German -er, the Swedish -are, the Icelandic –ari and the Gothic -areis. It was related to the Ancient Greek -ήριος (-ḗrios) and Old Church Slavonic -арь (-arĭ). In English, it was reinforced by the synonymous but unrelated Old French –or & -eor (Anglo-Norman variant -our), from the Latin -(ā)tor, from the primitive Indo-European -tōr. Muffler is a noun and mufflerless, unmufflered, demufflered & mufflered are adjectives; the noun plural is mufflers.

Scarf (pronounced skahrf)

(1) A

long, broad strip of wool, silk, lace, or other material worn about the neck,

shoulders, or head, for ornament or protection against cold, drafts etc.; a muffler.

(2) A

necktie or cravat with hanging ends (archaic).

(3) A

long cover or ornamental cloth for a bureau, table etc (rare).

(4) To

cover or wrap with or as if with a scarf or to use in the manner of a scarf

(verb).

(5) In

carpentry, a tapered or otherwise-formed end on each of the pieces to be

assembled with a scarf joint scarf joint (a lapped joint between two pieces of

timber made by notching or grooving the ends and strapping, bolting, or gluing

the two pieces together).

(6) In

whaling, a strip of skin along the body of the whale, a groove made to remove

the blubber and skin.

(7) In

steelmaking, to burn away the surface defects of newly rolled steel.

(8) To

eat, especially voraciously (often followed by down or up).

1545–1455: From the Old Norse skarfr (end cut from a beam), from skera (to cut) . The sense of a scarf being a piece of material cut from a larger piece is actually based on the use in carpentry, linked to the Swedish skarf & the Norwegian skarv (patch) and the Low German and Dutch scherf (scarf). The sense of eating quickly is a now almost extinct Americanism from 1955-1960, thought a variant of scoff, with r inserted probably through r-dialect speakers' mistaking the underlying vowel as an r-less ar. Etymologists have suggested other lineages such as a link with the Old Norman French escarpe and the Medieval Latin scrippum (pilgrim's pack) but the alternatives have never attracted much support. Scarf is a noun & verb and scarfie is a noun; the noun plural is scarves or scarfs. There is no established convention (and certainly no rule) about which plural form is "correct" when referring to the neckwear so all that can be recommended is consistency. In practice, "scarves" seems more commonly used of the clothing while "scarfs" must always be the spelling in the context of carpentry.

Until well into the twentieth century, muffler and scarf were used interchangeably but as the vocabulary associated with motor vehicles became commonplace, "muffler" became increasingly associated with the baffled mechanical device used to reduce the noise emanating from exhaust systems. The automotive use swamped the linguistic space and muffler became less associated with the neck accessory although it never wholly went away and the upper reaches of the fashion industry maintain the distinction and it of course remains a staple in literary fiction. Historically, of the garments, muffler was mostly British in use (Americans long preferring scarf) but scarf is now globally the most common form. One geographically specific use was the "scarfie", a New Zealand slang form which began as a reference to a student at the University of Otago, based on the association with the signature blue-and-yellow scarf said habitually to be worn to signify allegiance to the provincial rugby union team (the Otago Rugby Football Union). New Zealanders sometime in the mid-twentieth century abandoned mainstream religion and substituted worship of rugby and this was said to be something practiced with the greatest intensity at the University of Otago, the sense of group identity thought to have been reinforced by the country's only medical school having been located there for many decades. The other great cultural contribution to Western culture was their part in the history of the "chunder mile".

University of Otago Medical School.

The now-banned chunder mile was similiar in concept to the various "beer miles" still contested in some places, “chunder” being circa 1950s Australia & New Zealand slang for vomiting and of disputed origin. The rules were simple enough, contestants being required to eat a (cold) meat pie, enjoyed with a jug of (un-chilled) beer (a jug typically 1140 ml (38.5 fl oz (US)) at the start of each of the four ¼ mile laps and, predictably, the event was staged during the university's orientation week. Presumably, it was helpful that at the time the place was the site of the country’s medical school, thereby providing students with practical experience of both symptoms and treatments for the inevitable consequences. Whether the event was invented in Dunedin isn’t known but, given the nature of males aged 17-21 probably hasn’t much changed over the millennia, it wouldn’t be surprising to learn similar competitions, localized to suit culinary tastes, have been contested by the drunken youth of many places in centuries past. As it was, even in Dunedin, times were changing and in 1972, the Chunder Mile was banned “…because of the dangers of asphyxiation and ruptured esophaguses.”

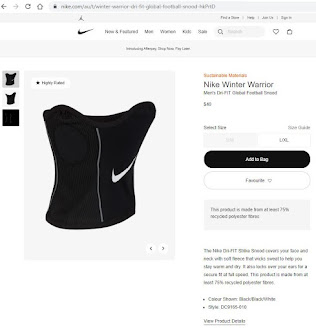

Although not universal (especially in the US), in the better magazines, fashion editors still like to draw a distinction between the two, a scarf defined as an accessory to enhance the look and made from fabrics like silk, cotton or linen whereas a muffler is more utilitarian, bulkier and intended to protect from the cold and thus made from wool, mohair or something good at retaining body-heat. That doesn't imply that inherently a muffler is associated with cheapness, the fashion houses able to see a market for a high-priced anything. Occasionally, muffler is used in commerce as a label of something which looks like a small blanket, worn over the shoulders and resembling an open poncho. They're said to offer great warmth.

So,

scarves and mufflers are both accessories worn around the neck for either or

both warmth and style but with historic differences in construction, size &

shape, those differences no longer of the same significance because the term “muffler”

has become a niche and “scarf” tends to prevail for most purposes. However, for those who enjoy pedantry (or

aspire to edit Vogue), the old conventions can be summarized thus:

Scarfs are usually rectangular or square in shape and available in many sizes and are made for a variety of materials including wool, silk, cotton or synthetic fabrics. They can be woven, knitted, or printed with patterns or designs. Scarves generally are long and narrow compared to mufflers and can be worn in many styles, the most popular including draped around the neck, wrapped, or knotted. Now often adopted as a fashion accessories to complement outfits or add a splash of color or texture, the seasonal choice will be dictated usually by temperature because, depending on material and thickness, a scarf can be as warming as a traditional muffler.

Mufflers are also long pieces of fabric, but they tend to be wider and thicker than the traditional, more decorative, scarves. Being bulkier and there for warmth, mufflers are often knitted or crocheted and may have a more substantial texture to enhance the thermal properties. The design of a muffler succeeds or fails on the basis of (1) the protection against the elements afforded and (2) the ease with which it snugly will wrap around the neck. Inherently that means they don’t always offer the same versatility in styling offered by scarves but because the surface area is large, a sympathetic choice of colors or patterns offers interesting possibilities. Strangely perhaps (and an indication of the way use has shifted), the neckwear worn by supporters of football clubs and such, although they are, in the conventional sense, mufflers, are always describes as scarfs although, in places like Cardiff Arms Park on a cold winter day, those with one wrapped around will be grateful for the warmth.

Avoiding the muffler

On cars, trucks and other vehicles with internal combustion engines (ICE) which generate their power by the noisy business of detonating hydrocarbons, mufflers are valued by most people because they make things much quieter. That's almost always good although in the right place, at the right time, the unmuffled sound of a BRM V16 at 12,000 rpm remains one of the great experiences of things mechanical and on the road, a well-designed chosen combination of engine and muffler can produce a pleasing exhaust note, witness the Daimler V8s of the 1960s. The BRM, like most racing cars in the era, was unmuffled because there's a price to be paid for quietness and that price is power, the addition to the exhaust system robbing ICE of efficiency. To try to have the best of both worlds (and seem to comply with the law), some inventive types use "outlaw" (or "special") pipes which work by offering exhaust gasses a "shortcut" to the atmosphere. In ICEs, there are both down-pipes and dump-pipes. Their functions differ and the term down-pipe is a little misleading because some down-pipes (especially on static engines) actually are installed in a sideways or upwards direction but in automotive use, most do tend downwards. A down-pipe connects the exhaust manifold to exhaust system components beyond, leading typically to first a catalytic converter and then a muffler (silencer), most factory installations designed deliberately to be restrictive in order to comply with modern regulations limiting emissions and noise. After-market down-pipes tend to be larger in diameter and are made with fewer bends improving exhaust gas flow, reducing back-pressure and (hopefully) increasing horsepower and torque. Such modifications are popular but not necessarily lawful. Technically, a dump-pipe is a subset of the down-pipes and is most associated with engines using forced aspiration (turbo- & some forms of supercharging). With forced-induction, exhaust gases exiting the manifold spin a turbine (turbocharger) or drive a compressor (supercharger) to force more of the fuel-air mixture into the combustion chambers, thereby increasing power. What a dump-pipe does is provide a rapid, short-path exit for exhaust gases to be expelled directly into the atmosphere before reaching a down-pipe. That obviously avoids the muffler, making for more power and noise, desirable attributes for the target market. A dump pipe is thus an exit or gate from the exhaust system which can be opened manually, electronically, or with a “blow-off” valve which opens when pressure reaches a certain level. In the happy (though more polluted) days when regulations were few, the same thing was achieved with an exhaust “by-pass” or “cut-out” which was a mechanical gate in the down-pipe and even then such things were almost always unlawful but it was a more tolerant time. Such devices, lawful and otherwise, are still installed.