Dimensionality (pronounced dih-men-shuhn-nal-i-tee or dahy-men-shuhn-nal-i-tee).

(1) The state or characteristic of possessing dimensions.

(2) In mathematics, engineering, computing, physics etc, the number of dimensions possessed or attributed to an object, space or concept; the nature of the dimensions, considered, in relation to each other or the external world.

(3) In architecture (usually in criticism or theory), as super-dimensionality, micro-dimensionality, complimentary-dimensionality etc, an expression used to critique the scale of designs.

Circa 1910: A coining of mathematicians said to date from the early twentieth century (though actual use may pre-date this), the construct was dimension + -ality. Dimension was from late fourteenth century late Middle English dimensioun, from the Anglo-French, from the Latin dīmēnsiōn-, from dīmēnsiō & dīmēnsiōnem, from dīmensus (measuring, measurement, dimension), perfect active participle of dīmētior (measured, regular), the construct being dis- (part’ separate; render asunder) + mētior (measure or estimate; distribute or mete out; traverse), from the Proto-Italic mētis, from the primitive Indo-European meh- (to measure). The suffix –ality was a compound affix, the construct being -al + -ity and equivalent to the French -alité and the Latin -ālitās. The -al suffix was from the Middle English -al, from the Latin adjectival suffix -ālis, or the French, Middle French and Old French –el & -al. It was use to denote the sense "of or pertaining to", an adjectival suffix appended (most often to nouns) originally most frequently to words of Latin origin, but since used variously and also was used to form nouns, especially of verbal action. The alternative form in English remains -ual (-all being obsolete). The –ity suffix was from the French -ité, from the Middle French -ité, from the Old French –ete & -eteit (-ity), from the Latin -itātem, from -itās, from the primitive Indo-European suffix –it. It was cognate with the Gothic –iþa (-th), the Old High German -ida (-th) and the Old English -þo, -þu & -þ (-th). It was used to form nouns from adjectives (especially abstract nouns), thus most often associated with nouns referring to the state, property, or quality of conforming to the adjective's description. The derived forms from mathematics and other disciplines (such as extradimentionality) are sometimes hyphenated. Dimensionality is a noun; the noun plural is dimensionalities.

Being inherently a thing of numbers, in both pure and applied mathematics, dimensionality matters. There is equidimensionality which, strictly speaking in the quality enjoyed by two (or more) dimensions exactly the same but the term has also been used in architecture as (1) a fancy way to say that things are (by mathematical standards) “roughly the same” and (2) a synonym for symmetrical. Nobody seems to have come up with “hetrodimensionality” or something like that, asymmetrical apparently adequate. In psychiatry, unidimensionality is the quality of measuring a single construct, trait, or other attribute; it's a clinical tool, an example of which is a unidimensional personality scale which would contain items related only to the respective concept of interest. It's not the same as the pop-psychology term "one-dimensional" which is an allusion to functional, intellectual, emotional etc limitations in individuals or institutions. A particular use of that appeared in the book One-Dimensional Man (1964) by German-American philosopher Herbert Marcuse (1898–1979). Marcuse argued modern capitalism had reduced culture to a technological rationality and individuals to mere economic units, their value measured only by their industrial productivity. Moreover, the genius of this system was that the false consciousness of the victims was manipulated to the point they became defenders of their own oppression.

Nondimensionality refers to quantity or measurement with no physical units attached, often represented as a ratio of two quantities that have the same units, such as the ratio of the diameter of a circle to its circumference (which is represented by the nondimensional quantity π, or pi). It’s not quite a revenge on the physicists who have identified certain particles with dimensions yet no mass, nondimensionality being useful in that relationships between different physical quantities can be expressed without the need to have specific units of measure. Unidimensionality (the opposite of multidimensionality) refers to a measurement or quantity involving only one dimension or aspect; it is used not to imply there is only one dimension but in situations where the critical quality can be described using a single variable or dimension. The classic examples of unidimensionality are the three dimensions length, width & breadth. Multidimensionality involves two or more dimensions. The companion terms “curse of dimensionality” and “blessing of dimensionality” are both commentaries of the volume of data available but reference not the data but the processes applied to the information. The curse of dimensionality is that in some cases there can be an unmanageable amount of data; there is simply too much information even to assess what should be discarded. However, for other purposes, the same data set could be invaluable, the volume making possible what once was not, thus the blessing of dimensionality.

Extradimensionality underlies string theory, a (highly) theoretical construct which has provided a number of speculative frameworks in an attempt to unify what are still considered the fundamental forces at work in the universe (gravity, electromagnetism, and the strong and weak nuclear forces). The essence of string theory in that the fabric of the universe is composed not of point-like particles in space but very small, one-dimensional forms (the nature of which varies according to the version of the theory) which act like “strings”, vibrating at different frequencies. The strings are said to exist in another dimensional space-time than the four with which we are familiar (length, width, depth & time) and some string theorists have suggested there may be ten or more dimensions. The most significant aspect of the behavior of the strings is said to be their interaction with both the space in which they exist and other strings in other spaces (although on the latter point some theorists differ). The intricate equations describing the strings and their dimensions has allowed very complex models to be built and from these, the handful of people of the planet who understand both the mathematics and their implications have drawn a number of inferences about the universe said variously to be “fascinating”, “speculative” and “nonsensical” and one of the delights of string theory is that it can be neither proved nor disproved. Word nerds however can be grateful to the stringers because they adopted “compactified”, the word describing the way the dimensions beyond the verifiable four are curled up (or scrunched) at scales so small they remain unobservable with current technology.

Superdimentionality

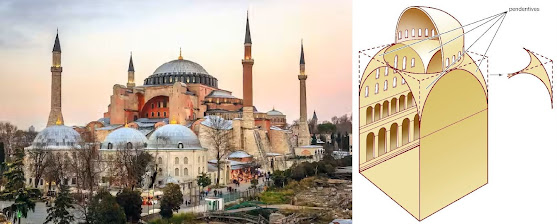

Superdimentionality is the application of exaggerated dimensions to designs, some of which actually get built. It a popular motif for the kitsch structures favored by tourist attractions of which Australia has many (the big pineapple, big prawn, big golfball, big lobster, big gumboot etc) but for Adolf Hitler (1889-1945; German head of government 1933-1945 & head of state 1934-1945), superdimentionality was the dominant concept for the entire Nazi empire; reichism writ large. The idea was well documented in the plans for Germania, the re-building of Berlin designed by a team under Albert Speer (1905–1981; Nazi court architect 1934-1942; Nazi minister of armaments and war production 1942-1945), the centerpiece of which was the monumental Volkshalle (People's Hall), sometimes referred to as the Große Halle (Great Hall). The hall would have seated 180,000 under a dome 16 times larger than that of St Peter's Basilica in the Vatican and in its vastness was a classic example of the representational architecture of the Third Reich. Although it’s obvious the structure as a whole was intended to inspire awe, the details also conveyed the subliminal messaging of much fascist propaganda, fixtures like doorways sometimes four times the usual height, the disconnection from human scale emphasizing the supremacy of the state.

Hitler also thought the materiel supplied to his military machine should be big. After being disappointed by proposals for the successors to the Bismarck-class ships to have the armament increased only from eight 15-inch (380 mm) to eight 16 inch (406 mm) canons, he ordered OKM (Oberkommando der Marine; Naval High Command) to design bigger ships. Although none were ever built, Germany lacking the facilities even to lay down the keels, the largest (the H-44) would have had eight 20-inch (508 mm) cannons. Even more to the Führer’s liking was the concept of the H-45, equipped with eight 31.5 inch (800 mm) Gustav siege guns but the experience of surface warfare at sea convinced Hitler the days of the big ships were over and he would even try to persuade the navy to retire all their capital ships and devote more resources to the submarines which, as late as 1945, he hoped might still prolong the war. However, he never lost faith in the promise of bigger and bigger tanks, an opinion share by none of the tank commanders who were appalled at the designs of some of the monstrosities he ordered prepared.

Hitler’s study in the Reich Chancellery (1939) (left) and his (rarely used) big desk in the corner, the big doors behind (right)

Perhaps surprisingly, there’s no record Hitler ever complained the Mercedes-Benz built for his use were too small but then they were, even by the standards to which popes, presidents and potentates were accustomed, big. Other heads of state weren’t so reticent and Charles De Gaulle (1890–1970; President of France 1958-1969), in 1965 aghast at the notion the state car of France might be bought from Germany or the US (it’s not known which idea he thought most appalling and apparently nobody bothered to suggest buying British) requested coachbuilder Henri Chapron (1886-1978) construct something with the necessary grandeur. The legend is, Le General’s only stipulations about his enlarged Citroën DS were (1) it had to be longer than the stretched Lincoln Continentals then on the White House fleet (John Kennedy (JFK, 1917–1963; US president 1961-1963) assassinated in Continental X-100 modified by Hess and Eisenhardt) and (2) the turning circle had to be tight enough to enter the Elysée Palace’s courtyard from the rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré and then pull up at the steps in a single maneuver.

Size matters: Citroën DS Le Presidentielle (left) and LBJ era stretched Lincoln Continental by Lehmann-Peterson of Chicago (right).

Carrosserie Chapron managed to fulfil both requirements although the contrast between the Citroën’s rather agricultural 2.2 litre (133 cubic inch) four-cylinder engine the 430 cubic inch (7.0 litre) V8 in Lyndon Johnson’s (LBJ, 1908–1973; US president 1969-1969) Lincoln was remarkable, De Gaulle probably regarding the additional displacement as typical American vulgarity. Chapron (apparently without great enthusiasm) began the build in 1965 and the project took three years; delivered just in time for the troubles of 1968, the slinky lines were much admired in the Élysée and in 1972, Chapron was given a contract to supply two really big four-door convertible (Le Presidentielle) SMs as the state limousines for Le Général’s successor, Georges Pompidou (1911–1974; President of France 1969-1974). First used for 1972 state visit of Elizabeth II (1926-2022; Queen of the UK and other places, 1952-2022), they remained in regular service until the inauguration of Jacques Chirac (1932–2019; President of France 1995-2007) in 1995, seen again on the Champs Elysees in 2004 during Her Majesty’s three-day state visit marking the centenary of the Entente Cordiale.

Mercedes-Benz 770K (W150), Berlin 1939.

Hitler though would have been impressed by

the big V8 although he would doubtless have pointed out the 7.7 litre (468

cubic inch) straight-8 in his Mercedes-Benz 770K was not only bigger but also

supercharged and he’d have found nothing vulgar in any of the American machine’s

dimensions. The 770Ks used by the Führer

were produced in two series (W07 (1930-1939) & W150 (1939-1943)) of what

the factory called the Grosser Mercedes (the Grand Mercedes) and while the earlier

cars were available to anyone with the money (seven between 1932-1935 purchased

by the Japanese Imperial household for the emperor’s fleet and adorned with the

family’s gold chrysanthemum), the W150s were made exclusively for the upper echelons of the Nazi Party although to smooth the path of foreign policy, some did end

up in foreign hands such as António Salazar (1889–1970) dictator of Portugal

1932-1968), Generalissimo Francisco Franco (1892-1975; Caudillo of Spain

1939-1975) & Field Marshal Mannerheim (commander-in-chief of Finnish defense

force 1939–1945 and president of Finland (1944–1946). Though large and impressive, by 1938 the

W07 was something of a engineering relic and although the demands of the military

were paramount in the economy, resources were found to update the Grosser to

the technical level of the more modern 540K by adopting a lower tubular chassis

with revised suspension (the de Dion axle at the rear something which should

have appeared on the post-war cars) and a new, five-speed, all synchromesh gearbox. Making the selection of first gear effortless was of

some significance because so much of the 770K’s time was spent at crawling

speed on parade duty but, despite the bulk (and the weight of the armored

versions with 1¾ inch (45 mm) glass could exceed 5500 kg (12,000

lb), speeds in excess of 160 km/h (100 mph) could be achieved provided one had

enough autobahn ahead although at that pace, even the 195 litre (52 US gallon,

43 Imperial gallon) fuel tank would soon have been drained. Some sources also claim five were built with

two superchargers, raising the top speed to 190 km/h (118 mph) but the tale may

be apocryphal.

Mercedes-Benz G4 during Hitler’s entry in Vienna following the Anschluss (the absorption of Austral into the Reich), 14 March 1938. The statue in the background is of the Archduke Charles Louis John Joseph Laurentius of Austria, Duke of Teschen (1771–1847) and often referred to as “Archduke Karl”, mounted on the Heldenplatz.

Also appealing to Hitler was the big, three-axle

G4 (W31). The factory developed six-wheel

(and ten-wheel for those with dual rear wheels) cross-country vehicles for

military use during the 1920s but after testing a number of the prototype G1s,

the army declined to place an order, finding them too big, too expensive and

too heavy for their intended purpose. Hitler

however, as drawn to big, impressive machines as he was to huge,

representational architecture, ordered them adopted as parade vehicles and the

army soon acquired a fleet of the updated G4, used eventually not only on

ceremonial occasions but also as staff and command vehicles, several known to have been specially

configured, some as baggage cars and at least one as a mobile communications centre,

packed with radio-telephony. Eventually,

between 1934-1939, fifty-seven were built, originally exclusively for the OKW (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (Armed Forces

High Command)) and OKH (Oberkommando des

Heeres (Army High Command)) but one was gift from Hitler to Franco and the Spanish

G4, one of few which still exists, was restored and remains in the royal garage

in Madrid. According to factory records,

all were built with 5.0, 5.3 & 5.4 litre straight-eight engines but there

is an unverified report of interview with Hitler’s long-time chauffeur, Erich

Kempka (1910-1975), suggesting one for the Führer’s exclusive use was built

with the 7.7 litre straight-eight used in the 770K Grosser. Most of the 770s were supercharged so, if

true, it's a tantalizing prospect but this story is widely thought apocryphal,

no evidence of such a one-off ever having been sighted.