Legion (pronounced lee-juhn)

(1) In the army of Ancient Rome, a military formation

which numbered between 3000-6000 soldiers, made up of infantry with supporting

cavalry.

(2) A description applied to some large military and paramilitary

forces.

(3) Any great number of things or (especially) as persons;

a multitude; very great in number (usually postpositive).

(4) A description applied to some associations of

ex-servicemen (usually initial capital).

(5) In biology, a taxonomic rank; a group of orders

inferior to a class; in scientific classification, a term occasionally used to

express an assemblage of objects intermediate between an order and a class.

1175–1225: From the Middle English legi(o)un, from the Old French legion (squad, band, company, Roman military unit), from the Latin legiōnem & legiōn- (nominative legiō) (picked body of soldiers; a levy of troops), the construct being leg(ere) (to gather, choose, read; pick out, select), from the primitive Indo-European root leg- (to gather; to collect) + -iōn The suffix –ion was from the Middle English -ioun, from the Old French -ion, from the Latin -iō (genitive iōnis). It was appended to a perfect passive participle to form a noun of action or process, or the result of an action or process. Legion & legionry are nouns, adjective & verb and legionnaire & legionary are nouns; the noun plural is legions.

The Bellevue Stratford and Legionella pneumophilia

The origin of Legionnaires’ disease (Legionella pneumophilia) was in the bacterium resident in the air-conditioning

cooling towers of the Bellevue Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia which in July

1976 was hosting the Bicentennial convention of the American Legion, an

association of service veterans; the bacterium was subsequently named Legionella.

The Legionella bacterium occurs

naturally and there had before been outbreaks of what came to be called Legionella pneumophilia,(a pneumonia-like

condition) most notably in 1968 but what

made the 1976 event different was the scale and severity which attracted investigation

and a review of the records which suggested the first known case in the United

States dated from 1957. Like HIV/AIDS,

it was only when critical mass was reached that it became identified as

something specific and there’s little doubt there may have been instances of Legionella pneumophilia for decades or

even centuries prior to 1957. The

increasing instance of the condition in the late twentieth century is most

associated with the growth in deployment of a particular vector of

transmission: large, distributed air-conditioning systems. Until the Philadelphia outbreak, the cleaning

routines required to maintain these systems wasn’t well-understood and indeed, the

1976 event wasn’t even the first time the Bellevue Stratford had been the

source two years earlier when it was the site of a meeting of the Independent

Order of Odd Fellows but in that case, fewer than two-dozen were infected and

only two fatalities whereas over two-hundred Legionnaires became ill thirty-four

died. Had the 1976 outbreak claimed only

a handful, it’s quite likely it too would have passed unnoticed.

That the 1976 outbreak was on the scale it was certainly affected the Bellevue-Stratford. Built in the Philadelphia CBD on the corner of Broad and Walnut Streets in 1904, it was enlarged in 1912 and, at the time, was among the most impressive and luxurious hotels in the world. Noted especially for a splendid ballroom and the fine fittings in its thousand-odd guest rooms, it instantly became the city’s leading hotel and a centre for the cultural and social interactions of its richer citizens. Its eminence continued until during the depression of the 1930s, it suffered the fate of many institutions associated with wealth and conspicuous consumption, its elaborate form not appropriate in a more austere age. As business suffered, the lack of revenue meant it was no longer possible to maintain the building and the tarnish began to overtake the glittering structure.

Although the ostentation of old never quite returned, in the post-war years, the Bellevue-Stratford did continue to operate as a profitable hotel until an international notoriety was gained in July 1976 with the outbreak of the disease which would afflict over two-hundred and, ultimately, strike down almost three dozen of the conventioneers who had been guests. Once the association with the hotel’s air-conditioning became known, bookings plummeted precipitously and before the year was out, the Stratford ceased operations although there was a nod to the architectural significance, the now deserted building was in 1977 listed on the US National Register of Historic Places.

The lure of past glories was however strong and in

1978-1979, after being sold, a programme described as a restoration rather than

a refurbishment was undertaken, reputedly costing a then impressive US$25 million,

the press releases at the time emphasizing the attention devoted to the air-conditioning

system. The guest rooms were entirely

re-created, the re-configuration of the floors reducing their number to under

six-hundred and the public areas were restored to their original appearance. However, for a number of reasons, business

never reached the projected volume and not in one year since re-opening did the

place prove profitable, the long-delayed but inevitable closure finally

happening in March 1986.

But, either because or in spite of the building being listed as

a historic place, it still attracted interest and, after being bought at a knock-down

price, another re-configuration was commenced, this time to convert it to the

now fashionable multi-function space, a mix of retail, hotel and office space, now

with the inevitable fitness centre and food court. Tellingly, the number of hotel rooms was

reduced fewer than two-hundred but even this proved a challenge for operators

profitably to run and in 1996, Hyatt took over.

Hyatt, although for internal reasons shuffling the property within their

divisions and rebranding it to avoid any reference to the now troublesome Stratford

name, benefited from the decision by the city administration to re-locate Philadelphia’s

convention centre from the outskirts to the centre and, like other hotels in

the region, enjoyed a notable, and profitable, increase in demand. It’s now called simply: The Bellevue Hotel.

Understandably, the Bellevue’s page on Hyatt’s website, although discussing some aspects of the building’s history such as having enjoyed a visit from every president since Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919; US president 1901-1909) and the exquisitely intricate lighting system designed by Thomas Edison (1847-1931) himself, neglects even to allude to the two outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease in the 1970s, the sale in 1976 noted on the time-line without comment. In a nice touch, guests may check in with up to two dogs, provided they don't exceed the weight limit 50 lb (22.67 kg) pounds individually or 75 lb (34 kg) combined. Part of the deal includes a “Dog on Vacation” sign which will be provided when registering; it's to hang on the doorknob so staff know what's inside and there's a dog run at Seger Park, a green space about a ½ mile (¾ km) from the hotel. Three days notice is required if staying with one or two dogs and, if on a leash, they can tour the Bellevue's halls but they're not allowed on either the ballroom level or the 19th floor where the XIX restaurant is located. A cleaning fee (US$100) is added for stays of up to six nights, with an additional deep-cleaning charge applicable for 7-30 nights.

Lindsay Lohan with some of the legion of paparazzi who, despite technical progress which has disrupted the primacy of their role as content providers in the celebrity ecosystem, remain still significant players in what is a symbiotic process.

Cadillac advertising, 1958.

Cadillac in 1958 knew their buyer profile and their agency’s choice of the Bellevue Stafford as a backdrop reflected this. They knew also to whom they were talking, thus the copywriters coming up with: “Not long after a motorist takes delivery of his new Cadillac, he discovers that the car introduces him in a unique manner. Its new beauty and elegance, for instance, speak eloquently of his taste and judgment. Its new Fleetwood luxury indicates his consideration for his passengers. And its association with the world’s leading citizens acknowledges his standing in the world of affairs.” That’s just how things were but as the small-print (bottom left of image) suggest, women did have their place as Cadillac accessories, a number of them in the photograph to look decorative in their “gowns by Nan Duskin”. Lithuania-born Nan Duskin Lincoln (1893-1980) in 1926 opened her eponymous fashion store on the corner of 18th & Sansom Streets and enjoyed such success she was soon able to purchase three buildings on Walnut Stereet which she converted into her flagship and for years it was an internationally-renowned fashion mecca. Ms Duskin was unusual in that despite have never been educated beyond the sixth grade, she was an advocate for fashion being taught at universities and while that may not seem revolutionary in an age when it’s probably possible to take a post-graduate degree in basket weaving, it was at the time a novel idea. She worked as a lecturer in design and criticism at Drexel University, the institution later establishing the Nan Duskin Laboratory of Costume Design. It was said of Ms Duskin that when she selected a wedding dress for brides-to-be, almost invariably they were delighted by the suggestion though she would lament the young ladies were not always so successful in their choice of grooms.

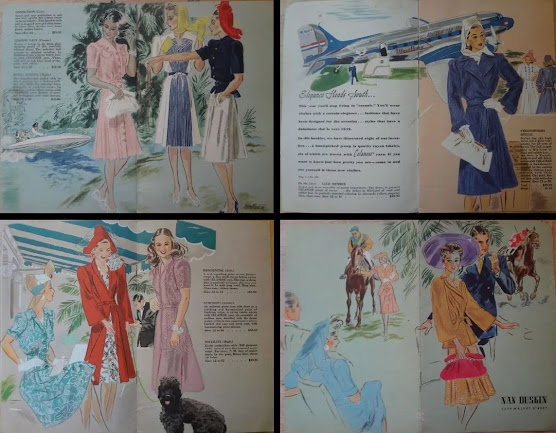

Nan Duskin brochure, 1942; While fashions change, slenderness never goes out of style and these designs are classic examples of “timeless lines”. Presumably, this brochure was printed prior to the imposition of wartime restrictions which resulted in such material being restricted to single color, printed on low-quality newsprint.

Responsible for bringing to Philadelphia the work of some European couture houses sometimes then not seen even in New York, there was nobody more responsible for establishing the city as a leading centre of fashion before her semi-retirement in 1958 when she sold her three stores to the Dietrich Foundation. Unashamedly elitist and catering only to the top-end of the market (rather like Cadillac in the 1950s), her stores operated more like salons than retail outlets and while things for a while continued in that vein after 1958, the world was changing and while the “best labels” continued to be stocked, the uniqueness gradually was dissipated until it was really just another store, little different from the many which had sought to emulate the model. In 1994, Nan Duskin filed for Chapter 11 Bankruptcy (which enables to troubled companies to continue trading while re-structuring) but the damage was done and in 1995 the businesses were closed. Nothing lasts forever and it’s tempting to draw a comparison with the way Cadillac “lost its way” during the 1980s & 1990s.