Phonetic (pronounced fuh-net-ik)

(1) Of

or relating to speech sounds, their production, or their transcription in

written symbols.

(2) Corresponding

to pronunciation; agreeing with pronunciation; spelling in accord with

pronunciation.

(3) Concerning

or involving the discrimination of non-distinctive elements of a language (in English,

certain phonological features, as length and aspiration, are phonetic but not

phonemic); denoting any perceptible distinction between one speech sound and

another, irrespective of whether the sounds are phonemes or allophones.

(4) As

a noun, (in Chinese writing) a written element that represents a sound and is

used in combination with a radical to form a character.

(5) In

the language of structural linguistics, relating to phones (as opposed to

phonemes).

1803:

From the New Latin phōnēticus, from the

Ancient Greek φωνητῐκός (phōnētikós) (vocal), the construct being

phōnēt(ós) (utterable; to be spoken (verbid of phōneîn (to make sounds; to speak))) + -ikos (the adjective suffix).

The source was the Latin phōnē

(sound, voice), from the primitive Indo-European bha- (to speak, tell, say).

The meaning "relating or pertaining to the human voice as used in

speech" was in use by 1861 but the technical use "phonetic science” (scientific

study of speech) was in the literature twenty years earlier. Phonetic is an adjective and a noun (in the

technical sense of a element in Chinese writing) and phonetically an adverb. Phonetical is an adjective which can correctly

be used in certain sentences but is largely synonymous with phonetic and thus

often potentially redundant. Fauxnetic

(the construct being faux (fake) + (pho)netic) exists to describe a respelling

system: not adequately indicating pronunciation and can be used humorously or

technically.

The

NATO Phonetic Alphabet

Phonetic alphabets were devised as radiotelephonic spelling systems

to enhance the clarity of voice-messaging in potentially adverse audio

environments, afflicted by factors such as the clatter of the battlefield, poor

signal quality or language barriers where differences in pronunciation can

distort understanding. If a universal radiotelephonic

spelling alphabet (substituting a code word for each letter of the alphabet) is

adopted, critical messages are more likely correctly to be understood.

The

NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) phonetic alphabet became effective in

1956 and soon became the established universal phonetic alphabet but the one

familiar today took some time to emerge, several adaptations earlier trialed. The early inventors and adopters of what were

then variously called voice procedure alphabets, (radio-)telephony alphabets

& (word-)spelling alphabets, were branches of the military anxious, as the

volume of radio communication increasingly multiplied, to adopt a standardized

set of standards as they had in Morse Code for cable traffic and semaphore for

signals. A surprising array of systems

were developed by the military and the cable & telephony operators which,

obviously worked well within institutions but as communications systems were

tending to become interconnected, the utility for interoperability was limited

by the confusion which could arise where the choices of name didn’t coincide.

Probably

the first genuinely global models were those standardized during the 1920s by

the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and International

Telecommunication Union (ITU), the latter adopted by many post offices (and

other authorities administering regional telephone systems). It featured mostly the names of cities across

the globe although substituted kilogramme (sic) for the Khartoum or Kimberley used earlier by others:

Amsterdam,

Baltimore, Casablanca, Denmark, Edison, Florida, Gallipoli, Havana, Italia,

Jerusalem, Kilogramme, Liverpool, Madagascar, New York, Oslo, Paris, Quebec,

Roma, Santiago, Tripoli, Uppsala, Valencia, Washington, Xanthippe, Yokohama,

Zurich.

City

names had long been a popular choice because they were usually well-known with

(at least in the English-speaking world), more-or-less standardized

pronunciations but the military, always interested in specific (if not general)

efficiencies, preferred words with no more than two syllables and preferably

one. The joint Army/Navy project in the

US (called the Able Baker alphabet after the first two code words) was adopted

across the entire service in 1941 and its utility, coupled with the wealth of

documentation available saw it quickly and widely used by allied forces,

something encouraged by their dependence on US materiel and logistical

support. In the muddle of war, adoption

was ad hoc and it seems nothing was formalized until the 1943 when the British

Royal Air Force (RAF) advised all stations that Able Baker was the RAF

standard, codifying what had for some time been standard operating

procedure. The Able Baker set used:

Able,

Baker, Charlie, Dog, Easy, Fox, George, How, Item, Jig, King, Love, Mike, Nan,

Oboe, Peter, Queen, Roger, Sugar, Tare, Uncle, Victor, William, X-ray, Yoke,

Zebra.

The

demands of war meant there was little time for linguistic sociology but after

the war, concerns began to be expressed that almost all (and by then dozens had

been created) the phonetic alphabets were decidedly English in composition. A new version incorporating sounds common to

English, French, and Spanish was proposed by the International Air Transport

Association (IATA), one of the alphabet soup of international organizations

which emerged after the formation of the United Nations (UN); their code-set

was, for civil aviation only, adopted in 1951 and was very similar to that used

today:

Alfa,

Bravo, Coca, Delta, Echo, Foxtrot, Gold, Hotel, India, Juliett, Kilo, Lima,

Metro, Nectar, Oscar, Papa, Quebec, Romeo, Sierra, Tango, Union, Victor,

Whiskey, eXtra, Yankee, Zulu.

Most

agreed the IATA system was technically better and certainly more suited to

communications conducted by a multi-language community, for whom many English

was neither a first nor sometimes even a familiar tongue. However, the military in this era was still

using the Able Baker system and the difficulties this created were practical,

many airfields and the overwhelming bulk of air-space shared between civil and

military operators. It was clear the need

for a universal phonetic alphabet was greater than ever and accordingly,

reviews were begun, soon coordinated by the newly formed NATO. After some inter-service discussion, NATO provided

a position paper proposing changing the words for the letters C, M, N, U, and X. This was submitted to the International Civil

Aviation Organization (IACO) and, having a world-wide membership structure, the

IAOC took a while to consider thing but eventually, a consensus was almost to

hand except for the letter N, the military faction wanting November, the civil Nectar

and neither side seemed willing to budge.

Seeing no progress, NATO in April 1955 engaged I a bit of linguistic

brinkmanship, the North Atlantic Military Committee Standing Group advising

that regardless of what the IACO did, the alphabet would “be adopted and made

effective for NATO use on 1 January 1956.”

This

created the potential for an imbroglio in that there were many civilian

institutions and not a few branches of militaries with which they interacted,

hesitant to adopt the alphabet for national use until the ICAO decided what to

do which would have created the unfortunate situation in which the NATO

Military Commands would be on the one system and others on a mixture. Fortunately, the ICAO responded with

new-found alacrity and approved the alphabet, November prevailing. NATO formalized the use with effect from 1

March 1956 and the ITU later adopted it which had the effect of it becoming the

established universal phonetic alphabet governing all military, civilian and

amateur radio communications. Although

it was substantially the work of other, particularly the various civil aviation

authorities around the world, because it was NATO which was most associated

with the final revision, it became known as the NATO Phonetic Alphabet.

Russian

military phonetic alphabet compared with NATO set.

There were objections. In the word-nerdy world of structural

linguistics, there are objections to the very phrase "phonetic

alphabet" because they don’t indicate phonetics and cannot function as genuine

phonetic transcription systems like the International Phonetic Alphabet,

reminding us the NATO system is actually the International Radiotelephony

Spelling Alphabet. Those few who note

the argument tend politely to agree and move on. There are also those who use the NATO set but

disapprove of the Americans, NATO, the West, capitalism etc; they call it

something else if they call it anything at all.

Then there are countries which speak languages other than English. English is the international language of

civil aviation so they’re stuck with that but foreign militaries and security

services often have their own sets.

There’s

never been the same interest in or effort devoted to a system of numeric code

words (ie the numbers from zero to nine) and the IMO defines a different set than

does the ICAO: 0 (Nadazero), 1 (Unaone), 2 (Bissotwo), 3 (Terrathree), 4 (Kartefour),

5 (Pantafive), 6 (Soxisix), 7 (Setteseven), 8 (Oktoeight) & 9 (Novenine). The divergence has never created much controversy

because the nature of the words which designated numbers tend not easily to be

confused with others and the fact they were often spoken is a context which

made obvious their numerical nature added to clarity. Indeed, although NATO created a comple set of ten names for numbers, the only ones recommended for use were : 3 (Tree), 4 (Fowler),

5 (Fife) & 9 (Niner), these the only ones thought potentially

troublesome. In practice, in NATO and

beyond, these are rarely used and that very rarity means they’re as likely to

confuse as clarify, especially if spoken between those who speak different

languages.

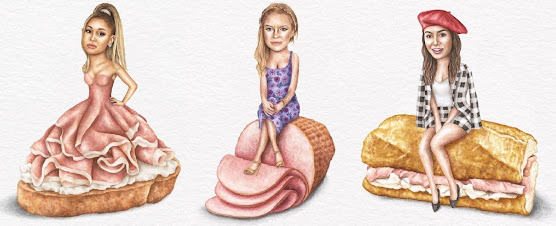

Pronunciation can of course be political so therefore can be contextual. Depending on what one’s trying to achieve, how one chooses to pronounce words can vary according to time, place, platform or audience. Some still not wholly explained variations in Lindsay Lohan’s accent were noted circa 2016 and the newest addition to the planet’s tongues (Lohanese or Lilohan) was thought by most to lie somewhere between Moscow and the Mediterranean, possibly via Prague. It had a notable inflection range and the speed of delivery varied with the moment. Psychologist Wojciech Kulesza of SWPS University of Social Sciences and Humanities in Poland identified context as the crucial element. Dr Kulesza studies the social motives behind various forms of verbal mimicry (including accent, rhythm & tone) and he called the phenomenon the “echo effect”, the tendency, habit or technique of emulating the vocal patters of one’s conversational partners. He analysed clips of Lilohan and noted a correlation between the nuances of the accent adopted and those of the person with who Ms Lohan was speaking. Psychologists explain the various instances of imitative behaviour (conscious or not) as one of the building blocks of “social capital”, a means of bonding with others, something which seems to be inherent in human nature. It’s known also as the “chameleon effect”, the instinctive tendency to mirror behaviors perceived in others and it’s observed also in politicians although their motives are entirely those of cynical self-interest, crooked Hillary Clinton’s adoption of a “southern drawl” when speaking in a church south of the Mason-Dixon Line a notorious example.

Memo: Team Douglas Productions, 29 July 2004.

Also of interest to students of nomenclature is the process by which the names of people can become objects applied variously. As Napoleon, Churchill and Hitler live on as Napoleonic, Churchillian and Hitlerite, on the internet is a body of the Lohanic. Universally, that’s pronounced lo-han-ick but Lindsay Lohan has mentioned in interviews that being a surname of Irish origin, it’s “correctly” low-en, a form she adopted early in 2022 with her first posting on TikTok where it rhymed with “Coen” (used usually for the surname “Cohen” which is of Hebrew origin and unrelated to Celtic influence). For a generation brought up on lo-han it must have been a syllable too far because it didn’t catch on and by early 2023, she was back to lo-han with the hard “h”. Curiously, while etymologists seem to agree that historically lo-en was likely the form most heard in Ireland, the popular genealogy sites all indicate the modern practice is to use lo-han so hopefully that’s the last word. However, the brief flirtation with phonetic h-lessness did have a precedent: When Herbie: Fully Loaded (2005) was being filmed in 2004, the production company circulated a memo to the crew informing all that Lohan was pronounced “Lo-en like Coen” with a silent “h”.