Kosher (pronounced koh-sher)

(1) In Judaism, a legal definition of food fit or

allowed to be eaten or used, according to the dietary or ceremonial laws of the

of the Talmud; in conformity with canonical texts or Rabbinical edict, the

kosher rules can be applied also to non-food items such as clothing.

(2) In Judaism, adhering to the laws governing

such fitness.

(3) In informal use (without any religious

connotations), proper, legitimate, genuine, authentic.

1851: From the From Yiddish כּשר (kosher), from Hebrew כָּשֵׁר (kāshēr, kasher and kashruth) (right, fit, proper), the Yiddish reflecting the original meaning. In the US, in the mid-nineteenth century, the forms kasher & coshar were also in use and beyond the Jewish community, the use as a general verbal shorthand for proper, legitimate, genuine, authentic etc dates from 1896 or the 1920s depending on source although it’s only “kosher” (the original, simplified form of the Hebrew) which endured thus. Kosher is a verb, adjective & adverb, kosherness is a noun, kosherize, koshering & koshered are verbs and kosherly an adverb. Because the state of kosherness is a matter of fact under the rules of the Talmud, the adjectives nonkosher & unkosher are often used though whether there are nuances which dictate the choice of which (or even if any such nuances are consistent) isn’t clear. Although it’s grammatically non-standard, kosher & non kosher are sometimes used as nouns. Even among those who tend to work in English or an English-Yiddish mix, the transitive verb “to kasher” is commonly used to describe the preparation of food to conform to Jewish law. As a modifier it’s applied as required thus formations such as kosher salt, kosher kitchen, kosher pickle etc.

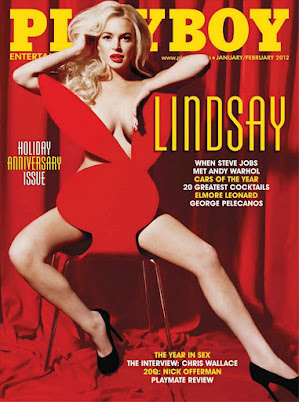

Lindsay Lohan on a visit to Westminster Synagogue with former special friend Samantha Ronson, London, March 2009.

The rules

for kosher foods are codified in the Torah in the kashrut halakha (dietary law) which exists mostly in Leviticus and

Deuteronomy. Food that conforms is

called kosher; that which does not is treif. Although

many elements of the rules are well known (no hare, hyrax, camel, and

pig; no shellfish or crustaceans, no creeping things that crawl the earth and

no mixing of meat and dairy at the same meal), for adherents, it can at the

margins be complex and sometimes the adjudication of the rabbi is needed

although, Judaism as practiced is not monolithic and while those who are

practicing will probably adhere to a core set or rules, the interpretation

varies between communities, their traditions and their level of observance. The history is also acknowledged by scholars

of the texts and it’s admitted many of the original rules about the consumption

of animal flesh were a kind of health code in the pre-refrigeration era, the

proscriptions applied to the animals which had been found most prone to spread

illness or disease if eaten after too long after slaughter or subject to

inadequate preparation. However, despite

advances in technology & techniques meaning health concerns no longer

apply, because of the long tradition, the rules have no assumed the function of

a devotional obligation.

McDonald's at Abasto Mall, Buenos Aires, Argentina, said to be the world’s only kosher McDonald's outside of Israel. On some days, it’s open until 2am.

The core rules of kosher food

(1) Animals must be slaughtered with a specific method:

The beast must be killed by a trained kosher slaughterer (a shochet) using a sharp blade without nicks

or imperfections. The animal must be

healthy and not suffer during the process.

(2) Only certain animals are considered kosher:

The Torah lists several permitted animals including cows, sheep, goats, and

deer. Pigs, camels, rabbits, and other animals are proscribed.

(3) If from the sea, river or lake, only fish

with fins and scales may be considered kosher; crustaceans & shellfish are

proscribed.

(4) Certain parts of an animal must not be eaten including the sciatic nerve and

certain fats.

(5) Insects which dwell or habitually crawl on

the ground are proscribed but flying and leaf-dwelling insects such as locusts

are permitted.

(6) Fruit and vegetables must carefully be

inspected for bugs and other contaminants; a contaminated item can be cleaned

if only touched by a bug but if partially eater, it must be discarded.

(7) Meat and dairy must never be mixed; not stored,

prepared, cooked or consumed together. Separate

utensils and dishes must be used for each.