Mug (pronounced muhg)

(1) A drinking cup, usually cylindrical in shape, having

a handle, and often of a heavy substance, as earthenware; the quantity it

holds.

(2) In slang, the face; an exaggerated facial expression;

grimace, as in acting; the mouth (mostly archaic).

(3) A thug, ruffian or other criminal (archaic).

(4) To assault or menace, especially with the intention

of robbery.

(5) In slang (especially in law enforcement &

correctional services), to photograph (a person), especially in compliance with

an official or legal requirement.

(6) A stupid, gullible or incompetent person.

(7) In slang (Britain, Australia, Singapore), to learn or

review a subject as much as possible in a short time (largely archaic, replaced

by cram).

1560–1570: Mug was originally Scots and northern English,

denoting an earthenware pot or jug. In

the sense of the small, usually cylindrical drinking vessel, origin was

probably Scandinavian; there was the Swedish mugg (earthen cup, jug) and the Norwegian & Danish mugge (pitcher; open can for warm drinks;

drinking cup), the sense “face” apparently transferred from the cups because

they tended often to be adorned with grotesque faces and from the same source

presumably was the Low German mokke

& mukke, the German Low German

Muck and the Dutch mok. The relationship to the Old Norse múgr (mass, heap (of corn)) and the Old

English muga (stack) is speculative. The derisive term “mug-hunter”, attested from

1883) was applied to those entering sporting contests solely to win prizes

(because they were often in the form of engraved cups). Mug is a noun, verb & adjective; the noun plural is mugs.

The use to describe a person's mouth or face dates from 1708, thought an extended sense of mug based on the old drinking mugs shaped like grotesque faces, popular in England from the seventeenth century. The sense of a "portrait or photograph in police records" spread universally with the growth in photography, the first known reference in the Annual Report of the [Boston Massachusetts] Chief of Police for 1873, when it was noted a notorious criminal who had for years been plying his trade all over the country attributed his arrest to “that ‘mug’ of mine that sticks in your gallery”. Despite that, mug-shot seems to have been used only since 1950. The meaning "stupid or incompetent person, dupe, fool, sucker" was part of underworld slang by 1851 and was commonly used to describe a criminal in the late nineteenth century, the phrase “mug's game” to describe some foolish, thankless or unprofitable activity emerged around the same time. The use since 1846 to describe an assault was influenced probably by it meaning "to beat up" (originally "to strike the face) in pugilism since 1818 and this seems to have led to the modern meaning of “mugging” as an attack upon the person of another with intent to rob; that’s noted from 1964. Some on-line dictionaries list mug in the African-American vernacular as a euphemism for motherfucker (usually in similes, eg "like a mug" or "as a mug"). In Australia, those for whom their only connection with horse racing is to once a year place a bet on the Melbourne Cup are known as "mug punters" but there has been research which suggests choosing a horse on the basis of the horse's name, the color of the jockey's silks (or some other apparently unrelated criterion) can be successful in up to 20% of cases.

Lindsay Lohan mug-shot merchandise is available in a variety of forms. There are mouse mats, socks, coasters, throw pillows, T-shirts, coffee mugs, face-masks, A-line dresses, hoodies and throw blankets.

Socks are US$19 a pair or US$17 for two / US$15 for three. The throw blanket is available in three sizes: Small, 40x56 inches (1010x760mm) @ US$28; Medium, 112x94 inches (152x127 cm) @ US$43; Large, 80x60 inches (203x152cm) @ US$56. Lightweight hoodies are available in sizes from XS-3XL, all at US$39. T-Shirts are available in sizes XS-XXL for US$7-17. Coasters are available in a packs of four for US$15. Mug-shot Mugs are available with either individual (with date of photo on reverse side) or multiple mug-shots from US$10-$22 with a discount for volume purchase. Facemasks are from US$12 with discounts if purchased in packs of four. A-Line dresses are available in sizes XXS-4XL for US$56.

Three approaches to the mug-shot aesthetic: Jenna Ellis (left), Rudy Giuliani (centre) & Donald Trump (right).

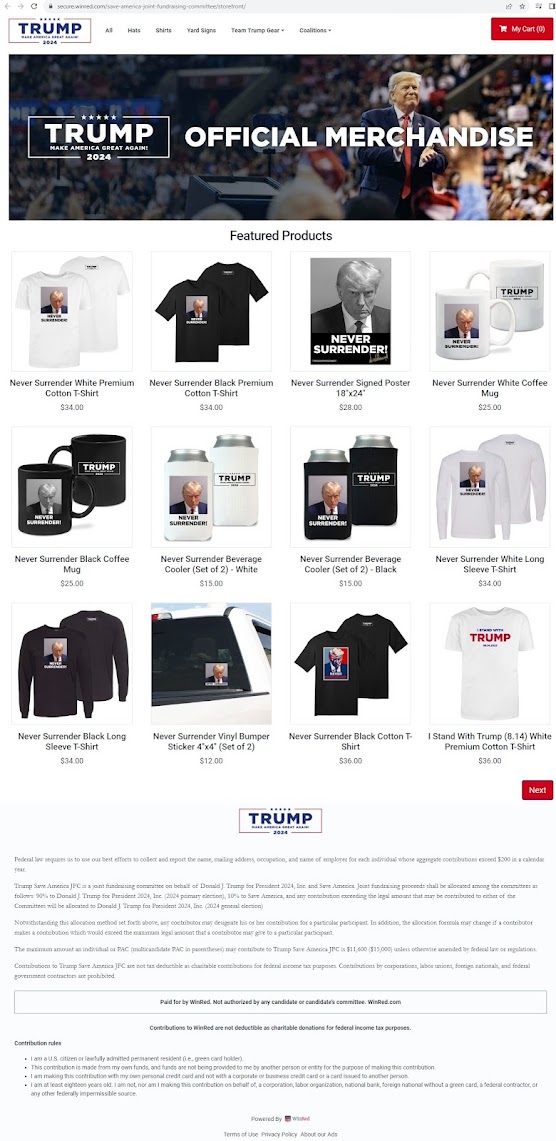

The recent release of the mug shots of Donald Trump and a number of his co-accused attracted comments about the range of expressions the subjects choose for the occasion. Legal commentators made the point it's actually not a trivial matter because prosecutors, judges and juries all often are exposed to a defendant's mug-shot and the photograph may have some influence on their thoughts and while judges are trained to avoid this, the effect may still be subliminal. Also, apart from the charges being faced, in the internet age, mug-shots sometimes go viral and modelling careers have been launched from their publication so for the genetically fortunate, there's some incentive to make the effort to look one's smoldering best.

The consensus appeared to be the best approach is to adopt a neutral expression which expresses no levity and indicates one is taking the matter seriously. On that basis, Lindsay Lohan was either well-advised or was a natural as one might expect from one accustomed to the camera's lens. Among Donald Trump's alleged co-conspirators there was a range of approaches and the consensus of the experts approached for comment seemed to be that Rudy Giuliani's (b 1944) was close to perfect as one might expect from a seasoned prosecutor well-acquainted with the RICO (Racketeering Influenced and Corrupt Organizations) legislation he'd so often used against organized crime in New York City. Many of the others pursued his approach to some degree although there was the odd wry smile. Some though were outliers such as Jenna Ellis (b 1984) who smiled as if she was auditioning for a spot on Fox News and, of course, some of the accused may be doing exactly that. However, the stand-out was Donald Trump (b 1946; US president 2017-2021) who didn't so much stare as scowl and it doubtful if his mind was on the judge or jury, his focus wholly on his own image of strength and defiance and the run-up to the 2024 presidential election. Regaining the White House wouldn't automatically provide Mr Trump with the mechanisms to solve all his legal difficulties but it'd be at least helpful. In the short term Trump mug-shot merchandize is available, the Trump Save America JFC (joint fundraising committee) disclosing the proceeds from the sales of Trump mug-shot merchandize will be allocated among the committees thus: 90% to Donald J. Trump for President 2024, Inc (2024 primary election) & 10% to Save America while any contribution exceeding the legal amount that may be contributed to either of the committees will be allocated to Donald J. Trump for President 2024, Inc (2024 general election).