Homologate (pronounced huh-mol-uh-geyt or hoh-mol-uh-geyt)

(1) To approve; confirm or ratify.

(2) To register (a specific model of machine (usually a car), engine or other component) in either general production or in the requisite number to make it eligible for racing competition(s).

(3) To approve or ratify a deed or contract, especially one found to be defective; to confirm a proceeding or other procedure (both mostly used in Scottish contract law).

1644: From the Latin homologāt

(agreed) & homologātus, past

participle of homologāre (to agree) from

the Ancient Greek homologeîn (to

agree to, to allow, confess) from homologos

(agreeing), the construct being homo-

(from the Ancient Greek ὁμός (homós) (same) + legein (to speak). Homologate, homologated and homologating are

verbs, homologation is a noun.

Once often used to mean “agree or confirm”, homologate is

now a niche word, restricted almost wholly to compliance with minimum

production numbers, set by the regulatory bodies of motorsport, to permit use

in sanctioned competition; the words "accredit, affirm, approbate, authorize, certify,

confirm, endorse, ratify, sanction, warrant & validate etc" are otherwise

used for the purpose of agreeing or confirming. It exists however still in Scottish law as a

legal device, used (now rarely) retrospectively to declare valid an otherwise defective contract. The best known application was to validate contracts of

marriage where some technical defect in the legal solemnities had rendered the union

void. In such cases case a court could hold the

marriage “. . . to be homologated by the subsequent marriage of the parties”. It was a typically Scottish, common-sense application of the law, designed originally to avoid children being declared bastards (at a time which such a label attracted adverse consequences for all involved), vaguely analogous with a “contract by acquiescence” from contract law though

not all were pleased: one dour Scottish bishop complained in 1715 that homologate

was a "hard word".

Case

studies in homologation

In 1962, fearing the effectiveness of Jaguar’s new XKE (E-Type) which looked faster even than it was, Ferrari created a lighter, more powerful version of their 250 GT, naming the new car 250 GTO (Gran Turismo Omologato (Grand Touring Homologated)). The regulatory body, the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA) required a production run of at least one-hundred for a car to be homologated for the Group 3 Grand Touring Car class but Ferrari built only 33, 36 or 39 (depending on how one treats the variations and 36 is most quoted) 250 GTOs, thus encouraging the myth the car violated the rules. However, as was acknowledged at the time, the FIA regarded the 250 GTO as a legitimate development the 250 GT Berlinetta SWB (Short wheelbase), homologation papers for which had been first issued in 1960 with variations, including the GTO, approved between 1961-1964. They’re now a prized item, one selling in 2018 for a world-record US$70 million which makes it the second most expensive car ever sold, the sum exceeded only by the US$142 million paid in 2022 for one of the two Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR Uhlenhaut gull-wing coupés.

1965 Ferrari 250 LMThe FIA’s legislative largess didn’t extend to Ferrari’s next development for GT racing, the 250 LM. The view of il Commendatore was the 250 LM was an evolution as linked to the 250 GT’s 1960 homologation papers as had been the 250 GTO and thus deserved another certificate of extension. This was too much for the FIA which pointed out 250 LM (1) was mid rather than front-engined, (2) used a wholly different body and (3) used a different frame and suspension. Neither party budged so the 250 LM could run only in the prototype class until 1966 when it gained homologation as a Group 4 Sports Car. Although less competitive against the true prototypes, it’s speed and reliability was enough for a private entry to win the 1965 24 Hours of Le Mans, a Ferrari’s last victory in the race until 2023. One quirk of the 250 LM was that when the FIA ruled against its homologation, the point of retaining the 3.0 litre displacement became irrelevant and most 250 LMs used a 3.3 litre engine and when fitted with the enlarged power-plant, under Ferrari’s naming convention, the thing properly should have been called a 275 LM.

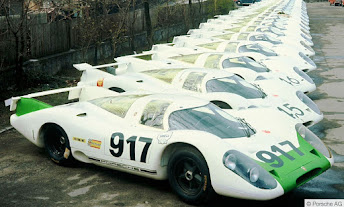

1969 Porsche 917In 1969, needing to build twenty-five 917s to be granted homologation, Porsche did... sort of. When the FIA inspectors turned up to tick the boxes, they found the promised twenty-five cars but most were in pieces. Despite assurances there existed more than enough parts to bolt together enough to qualify, the FIA, now less trusting, refused to sign off, despite Porsche pointing out that if they assembled them all, they'd then just have to take them apart to prepare them for the track. The FIA conceded the point but still refused to sign-off. Less than a month later, probably nobody at the FIA believed Porsche when they rang back saying twenty-five completed 917s were ready for inspection but the team dutifully re-visited the factory. There they found the twenty-five, lined-up in a row. The FIA delegation granted homologation, declining the offer of twenty-five test-drives.

By the mid 1950s, various NASCAR (National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing) competitions had become wildly popular and the factories (sometimes in secret) provided support for the racers. This had started modestly enough with the supply of parts and technical support but so tied up with prestige did success become that soon some manufacturers established racing departments and, officially and not, ran teams or provided so much financial support some effectively were factory operations. NASCAR had begun as a "stock" car operation in the literal sense that the first cars used were "showroom stock" with only minimal modifications. That didn't last long, cheating was soon rife and in the interests of spectacle (ie higher speeds), certain "performance enhancements" were permitted although the rules were always intended to maintain the original spirit of using cars which were "close" to what was in the showroom. The cheating didn't stop although the teams became more adept in its practice. One Dodge typified the way manufactures used the homologation rule to effectively game the system. The homologation rules (having to build and sell a minimum number of a certain model in that specification) had been intended to restrict the use of cars to “volume production” models available to the general public but in 1956 Dodge did a special run of what it called the D-500 (an allusion to the number built to be “legal”). Finding a loophole in the interpretation of the word “option” the D-500 appeared in the showrooms with a 260-hp V8 and crossed-flag “500” emblems on the hoods (bonnet) and trunk (boot) lids, the model’s Dodge’s high-performance offering for the season. However there was also the D-500-1 (or DASH-1) option, which made the car essentially a race-ready vehicle and one available as a two-door sedan, hardtop or convertible (the different bodies to ensure eligibility in NASCAR’s various competitions). The D-500-1 was thought to produce around 285 hp from its special twin-four-barrel-carbureted version of the 315 cubic inch (5.2 litre) but more significant was the inclusion of heavy-duty suspension and braking components. It was a successful endeavour and triggered both an arms race between the manufacturers and the ongoing battle with the NASCAR regulators who did not wish to see their series transformed into something conested only by specialized racing cars which bore only a superficial resemblance to the “showroom stock”. By the 2020s, it’s obvious NASCAR surrendered to the inevitable but for decades, the battle raged.

1970 Plymouth Superbird (left) and 1969 Dodge Daytona (right) by Stephen Barlow on DeviantArt. Despite the visual similarities, the aerodynamic enhancements differed between the two, the Plymouth's nose-cone less pointed, the rear wing higher and with a greater rake.

By 1969 the NASCAR regulators had fine-tuned their rules restricting engine power and mandating a minimum weight so manufacturers resorted to the then less policed field of aerodynamics, ushering what came to be known as the aero-cars. Dodge made some modifications to their Charger which smoothed the air-flow, labelling it the Charger 500 in a nod to the NASCAR homologation rules which demanded 500 identical models for eligibility. However, unlike the quite modest modifications which proved so successful for Ford’s Torino Talladega and Mercury’s Cyclone Spoiler, the 500 remained aerodynamically inferior and production ceased after 392 were built. Dodge solved the problem of the missing 108 needed for homologation purposes by introducing a different "Charger 500" which was just a trim level and nothing to do with competition but, honor apparently satisfied on both sides, NASCAR turned the same blind eye they used when it became clear Ford probably had bent the rules a bit with the Talladega. Not discouraged by the aerodynamic setback, Dodge recruited engineers from Chrysler's aerospace & missile division (which was being shuttered because the Nixon-era détente had just started and the US & USSR were beginning their arms-reduction programmes) and quickly created the Daytona, adding to the 500 a protruding nosecone and high wing at the rear. Successful on the track, this time the required 500 really were built, 503 coming of the line. NASCAR responded by again moving the goalposts, requiring manufacturers to build at least one example of each vehicle for each of their dealers before homologation would be granted, something which typically would demand a run well into four figures. Plymouth duly complied and for 1970 about 2000 Superbirds (NASCAR acknowledging 1920 although Chrysler insists there were 1,935) were delivered to dealers, an expensive exercise given they were said to be invoiced at below cost. Now more unhappy than ever, NASCAR lawyered-up and drafted rules rendering the aero-cars uncompetitive and their brief era ended. So extreme in appearance were the cars they proved at the time sometimes hard to sell and some were actually converted back to the standard specification to get them out of the showroom. Views changed over time and they're now much sought by collectors, the record price the US$1.43 million realized in January 2023 at a Mecum auction in the pleasingly named Kissimmee, Florida. That car was an exceptional example, one of only 70 built with the 426 cubic inch (7.0 litre) Street Hemi V8 and one of the 22 of those with the four-speed manual transmission.

1969 Ford Mustang Boss 429

NASCAR could however be helpful, scratching the back of those who scratched theirs. For the Torino and Cyclone, Ford was allowed to homologate their Boss 429 engine in a Mustang, a model not used in stock car racing. Actually, NASCAR had been more helpful still, acceding to Ford's request to increase the displacement limit from 427 to 430 cubic inches, just to accommodate the Boss 429. There was a nice symmetry to that because in 1964, Ford had been responsible for the imposition of the 427 limit, set after NASCAR became aware the company had taken a car fitted with a 483 cubic inch engine to the Bonneville salt flats and set a number of international speed records. The car used on the salt flats was one which NASCAR had banned from its ovals after it was found blatantly in violation of homologation rules so there was unlikely to be much leeway offered there.

1971 Ford Falcon GTHO Phase III

Australian manufacturers were (mostly) honest in their homologation programmes, Ford’s GTHO, Chrysler’s R/T Charger and Holden’s L34 and A9X were produced in accordance both with the claimed volumes and technical specification. However, they weren't always so punctilious. Ford's RPO83 (Regular Production Option #83) was a run of XA Falcon GTs completed late in 1973 which included many of the special parts intended for the aborted GTHO Phase IV and although, on paper, that seemed to make the things eligible for use in competition, it transpired the actual specification of various RPO83 cars wasn't consistent and didn't always match the nominal parts list. History has been generous however and generally it's conceded that in aggregate, the parts subject to the homologation rules appear to have been produced in the requisite number. By some accounts, this included counting the four-wheel disk brakes used on the luxury Landau hardtops but CAMS (the Confederation of Australian Motor Sport, at the time the regulatory body) was in the mood to be accommodating.

No homologation issues: Between 1938-2003, Volkswagen produced 21,529,464 Beetles (officially the VW Type 1).