Cammer (pronounced kham-ah)

(1) A content-provider who uses a webcam to distribute imagery on some basis (applied especially to attractive young females associated with the early use of webcams).

(2) Slang for a V8 engine produced in small numbers by Ford (US) in the mid-late 1960s.

(3) A general term for any camera operator (now less common because the use in the context of webcam feeds prevailed).

1964: A diminutive of single overhead cam(shaft). Cam was from the sixteenth century Middle English cam, from the Dutch kam (cog of a wheel (originally, comb)) and was cognate with the English comb, the form preserved in modern Dutch compounds such as kamrad & kamwiel (cog wheel). The association with webcams began in the mid-1990s, cam in that context a contraction of camera. The Latin camera (chamber or bedchamber) was from the Ancient Greek καμάρα (kamára) (anything with an arched cover, a covered carriage or boat, a vaulted room or chamber, a vault) of uncertain origin; a doublet of chamber. Dating from 1708, it was from the Latin that Italian gained camera and Spanish camara, all ultimately from the Ancient Greek kamára and the Old Church Slavonic komora, the Lithuanian kamara and the Old Irish camra all are borrowings from Latin. Cammer was first used in 1964 as oral shorthand for Ford’s 427 SHOC (single overhead camshaft) V8 engine, the alternative slang form being the phonetic “sock” and it became so associated with the one item that “cammer” has never been applied to other overhead camshaft engines. The first web-cam (although technically it pre-dated the web) feed dates from 1991 and the first to achieve critical mass (ie “went viral”) was from 1996. Cammer is a noun; the noun plural is cammers. While cammer is the generic term for those content providers distributing material captured with webcams, "cam-girl" describes the most popular of the breed.

The word came be used for photographic devices as a clipping of the New Latin camera obscura (dark chamber) a black box with a lens that could project images of external objects), contrasted with the (circa 1750) camera lucida (light chamber), which used prisms to produce an image on paper beneath; it was used to generate an image of a distant object. Camera was thus (circa 1840) adopted in nineteenth century photography because early cameras used a pinhole and a dark room. The word was extended to filming devices from 1928. Camera-shy (not wishing to be photographed) dates from 1890, the first camera-man (one who operates a camera) recorded in 1908. The first webcam feed (pre-dating the public availability of the www (world wide web) which permitted feeds to the wild), dates from 1991.

jennicam.org (1996-2003)

It wasn’t the internet’s first webcam feed, that seems to have been one in started in 1991 (before the worldwideweb was available to the public) aimed at a coffee machine in a fourth floor office at the University of Cambridge's Computer Science Department, created by scientists based in a lab the floor below so they would know whether to bother walking up a flight of stairs for a cup, but in 1996, nineteen year-old Jennifer Ringley (b 1976), from a webcam in her university dorm room, broadcast herself live to the whole world, 24/7. With jennicam.org, she effectively invented "lifecasting" and while the early feed was of grainy, still, monochrome images (updated every fifteen seconds) which, considered from the twenty-first century, sounds not interesting and hardly viral, it was one of the first internet sensations, attracting a regular following of four-million which peaked at almost twice that. According to internet lore, it more than once crashed the web, seven million being a high proportion of the web users at the time and the routing infrastructure then wasn't as robust as it would become. Tellingly, Ms Ringley majored in economics which explains the enticingly suggestive title "jennicam" whereas the nerds at Cambridge could think of nothing more catchy than "xcoffee" although for coffee fiends, that would have been compelling.

Jenni and pussy.

Although there were more publicized moments, jennicam.org was mostly a slideshow of the mundane: Jennifer studying at her desk, doing the laundry or brushing her teeth but it hinted at the realisation of earlier predictions, pop artist Andy Warhol's (1928–1987) "everybody will be famous for 15 minutes" and the "global village" discussed by Marshall McLuhan's (1911-1980) in The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man (1962) and Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1964). While not exactly pre-dating reality television (which in some forms existed in the 1950s), jennicam.org was years before the genre became popular and was closer to real than the packaged products became.

The 1964 Ford 427 SOHC (the Cammer)

There was cheating aplenty in 1960s NASCAR (National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing) racing but little of it was as blatant as Chrysler in 1964 putting on the grid their 426 HEMI V8, a pure racing engine, in what was supposed to be a series for mass-produced vehicles. Whatever the legal position (and the corporation did check before fielding the thing), it was hardly in the spirit of gentlemanly competition though in fairness to Chrysler, it didn't start it, NASCAR for years something of a parallel universe. In 1957, the AMA (Automobile Manufacturers AssociationA) had announced a ban on auto-racing and the public positions of GM (General Motors), Ford and Chrysler supported the stand, leaving the sport to dealer and privateers although, factory support of these operations was hardly a secret. NASCAR liked things this way believing the popularity of their “stock cars” relied on the vehicles raced being close to (ie "in the condition of those in the dealer's stock of what was for sale") what was available for purchase by the general public. Additionally, they wished to maintain the sport as affordable even for low budget teams and the easy way to do this was restricting the hardware to mass-produced, freely available parts, thereby leveling the playing field. It was a noble aim and the façade was maintained until the summer of 1962 when Ford announced it was going to "go racing". Market research had identified the competitive advantage to be gained from motorsport in an era when, uniquely, the demographic bulge of the baby-boomers, unprecedented prosperity and cheap gas (petrol) would coalesce, Ford understanding that in the decade ahead, a historically huge catchment of 17-25 year old males (the then youthful baby-boomers) with high disposable incomes or available credit were there to be sold stuff and they’d likely be attracted to fast cars. Thus began Ford's "Total Performance" era which would see successful participation in just about everything from rally courses to the Formula One circuits, including four memorable victories at the Le Mans twenty-four hour endurance classic.

The market leader, the more conservative GM, said they would "continue to abide by the spirit of the AMA ban" and, despite the scepticism of some, it seems they meant it because their racing development was halted though not without a parthian shot, Chevrolet in 1963 providing their preferred team a 427 cubic inch (7 litre) engine that came to be known as the "mystery motor". It stunned all with its pace but, being prematurely delivered, lacked reliability and, after a few races, having proved something, GM departed, saving NASCAR the bother of the inevitable squabble over eligibility.

1961 Ford Galaxie Starliner (left) & 1962 Galaxie with “distinguished hardtop styling” (aka “boxtop”, right).

Ford stayed and cheated, though not yet with engines. The aerodynamic qualities the 1960-1961 Galaxie Starliner, possessed by virtue of its gently sloping rear roof-line, generated both speed and stability on the NASCAR ovals; that made it a successful race-car but in the showrooms, after some early enthusiasm, sales dropped so it was replaced in 1962 with an implementation of the “formal” style which had been so well-received when used on the Thunderbird. As the marketing department predicted (or, more correctly, worked out from the results of their focus-group sessions), what they called “distinguished hardtop styling” proved more commercially palatable but while customers may have been seduced, the physics of fluid dynamics didn’t change and the “buffeting” induced at speeds above 140 mph (225 km/h) limited performance, adversely affected straight-line stability (especially when in close proximity to other cars); it also increased fuel consumption, in distance racing especially, something as significant as weight, speed and power. What the “distinguished hardtop styling” had done was make the Galaxie less competitive on the circuits, the loss of up to 3 mph (5 km/h) in top speed the difference being winning and losing; putting on the lipstick had produced a pig. Ford’s NASCAR teams dubbed the look the “boxtop”, boxes not noted for their fine aerodynamic properties and years later, Chrysler too would discover just how significant at high speed is the slope of the rear roofline.

Beware of imitations: Images from Ford's 1962 Galaxie Starlift "brochure" which didn't fool NASCAR.

Quickly to regain the lost aerodynamic advantage, Ford fabricated a handful of detachable fibreglass hard-tops which could be “bolted on”, essentially transforming a Galaxie convertible back into something as slippery (and even a little lighter) as the previous Starliner. Having no intention of incurring the expense of designing and engineering them to an acceptable consumer standard (which they knew few anyway would buy) Ford simply gave the hand-made plastic roof the name “Starlift”, allocated a part-number and even mocked-up a brochure for NASCAR to read. Although on paper it appeared a FADC (factory-authorized dealer accessory) like any other (floor-mats, mud flaps etc), an inspection of the device revealed it was obviously phoney, the rear passenger glass on each side not fitting the sloping C-pillar, demanding the use of a pair of tacked-on plastic fillers to close the gap and it was obvious the thing wasn’t close to being waterproof. NASCAR outlawed the scam.

The 483 cid Galaxie Starlift at speed, Bonneville, October 1962.

However, because five Starlift-equipped Galaxie convertibles had qualified for an race at Atlanta (postponed before the ban was imposed), they were permitted to run in the re-scheduled event and on the only occasion it was raced in NASCAR competition it won, the 100% win-record ranking it with the exquisite Mercedes-Benz W165 Voiturette created for the 1939 Tripoli Grand Prix in Libya among the sport’s most successful models. Banned from the circuits though it was, Ford did manage to give the Starlift one final fling. In October 1962, one fitted with an “experimental” version of the FE V8 with a displacement of 483 cubic inches (7.9 litres) was taken to Bonneville where it was used to set a slew of international speed records, clocked at 182.19 mph (293.21 km/h) and averaging 163.91 mph (263.79 km/h) over 500 miles (804.67 km). Noting the big numbers, NASCAR took the opportunity to impose a 7 litre (expressed in the US usually as "427 cid (cubic inch displacement)) capacity limit, one rule that was easy to enforce.

Hobbled by the “distinguished hardtop styling”, Ford managed to win only another four races in a season dominated by sleek Pontiacs but the engineers solved the problem in early 1963 with the “sports hardtop” roofline, a compromise which pleased both the pubic buying cars and the teams racing them. Remarkably, the revision to the roofline, in conjunction with increasing engine displacement from 406 cubic inches (6.6 litres) to 427 (strictly speaking it was 426 (7.0)) created one of the era’s more improbably successful race cars which enjoyed great success in saloon car events in England, Europe, South Africa, Australia & New Zealand until the lighter and more nimble Mustang became available.

Ford, which while enjoying great success in 1963 had actually adhered to the engine rules, responded to Chrysler’s 426 HEMI (which had dominated the 1964 season) within a remarkable ninety days with a derivation of their 427 FE in which the pushrods which activated the valves were with two SOHCs (single overhead camshafts), permitting higher engine speeds and valve angles producing more efficient combustion, thereby gaining perhaps a hundred horsepower. The engine, officially called the 427 SOHC, was nicknamed the Cammer (although some, noting the acronym, called it the "sock"). The problem for NASCAR was that neither the 426 HEMI nor the 427 Cammer existed in a car which could be bought from a showroom.

Not best pleased, NASCAR was mulling over this changed to thing carefully curated ecosystem when Chrysler responded to the 427 Cammer by demonstrating a mock-up of their 426 HEMI with a pair of heads using DOHC (double overhead camshafts) and four valves per cylinder instead of the usual two. Fearing an escalating war of technology taking their series in an undesired direction, in October 1964, NASCAR cracked down and issued new rules for the 1965 season. Although retaining the 427 cubic inch limit, engines now had to be mass-production units available for general sale and thus no hemi heads or overhead camshafts would be allowed The rule change had been provoked also by an increasing death toll as speeds had gone beyond what the circuits had been designed to safely to handle and certainly the capabilities of the available tyres.

That meant Ford’s 427 FE was eligible but Chrysler’s 426 HEMI was not and a disgruntled Chrysler withdrew from NASCAR, shifting their efforts to drag-racing where the rules of the NHRA (National Hot Rod Association) were more accommodating (while it's not clear if Chrysler complied even with those, the NHRA, attuned to hosting the spectacular, welcomed them anyway). In 1965, Chrysler seemed happy with the 426 HEMI's impact over the quarter-mile and Ford seemed happy being able to win just about every NASCAR race. Not happy was NASCAR which was watching crowds and revenue drop as the audience proved less interested in a sport where results had become predictable, their hope the rule changes would entice GM back to motorsport not realised. NASCAR audiences were a tribal lot and to attract the "Ford people", "GM people" and "Chrysler people", competitive cars from each needed to be fielded.

It was 1967 before everybody was, (more or less) happy again. Chrysler, which claimed it had intended always to make the 426 HEMI available to the general public and that the 1964 race programme had been just part of engineering development, for 1966 introduced the 426 Street HEMI, a detuned version of the race engine, making it a general-production option for just about any car in which it would fit (and soon they'd use a metaphorical shoehorn to force it into places it really didn't fit). Of the 11,000-odd sold between 1966-1971, most ended up in two door sedans and hardtops but there were also some 200 convertibles and, in the first year of availability, a reputed five were installed in Dodge Coronet four-door sedans (the industry legend being two were special orders for the FBI (Federal Bureau of Investigation) although Chrysler did decline one request for a Street HEMI station wagon. NASCAR responded quickly, announcing the HEMI now complied with the rules and was, with a few restrictions on the induction side (the race cars were permitted only a single carburetor while the street versions were sold only in "dual-quad" configuration with a pair of in-line, four barrel carburetors) was welcome back. Ford assumed NASCAR needed them more than they needed NASCAR and announced they would be using the 427 Cammer in 1966. NASCAR, feeling trapped its own precedent of having tolerated the HEMI in 1964, conceding only that Ford could follow Chrysler’s earlier path, saying the 427 Cammer would be regarded “…as an experimental engine in 1966… (to) …be reviewed for eligibility in 1967." In other words, eligibility depended still on mass-production (ie "mass" as defined by NASCAR's minimum annual production threshold of 500 and "production" meaning available to the general public in showrooms).

427 SOHC installed in a replica (by ERA) of a 1966 Shelby American AC Cobra 427 S/C (Semi-Competition).

Ford, although unable easily to create a 427 Street Cammer, recalled the Starlift trick and announced the SOHC was now available as a production item. That was, at best, economical with the truth, given not only could nobody walk into a showroom and buy a car with a 427 Cammer under the hood but it seemed at the time not always possible to purchase one even in a crate. Realising the futility of kicking the can down the road, NASCAR decided to kick it to the umpire, hoping all sides would abide by the decision, referring the matter to the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (the FIA; the International Automobile Federation), the world governing body for motor-sport, at that point not yet the byword for dopiness it would become. Past-masters at compromise, the FIA approved the 427 Cammer but imposed a weight handicap on any car in which it was used.

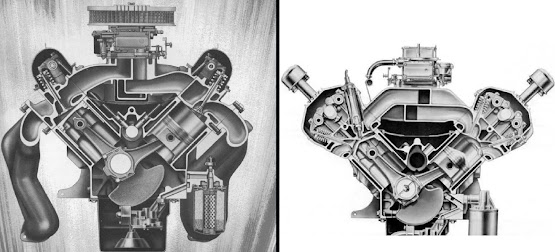

Cutaway Ford FE V8s: the 427 (left) and 427 SOHC (right).

Ford called that not just unfair but also unsafe, citing concerns at the additional stress the heavier vehicles would place of suspension and tyres, adding their cars couldn’t “… be competitive under these new rules." Accordingly, Ford threatened to withdraw from NASCAR in 1966 but found the public’s sympathy was with Chrysler which had done the right thing and made their engine available to the public. Ford sulked for a while but returned to the fray in late 1966, the math of NASCAR’s new rules having choked the HEMI a little so the 427 FE remained competitive, resulting in the curious anomaly of the 426 Street HEMI running dual four-barrel induction while on the circuits only a single carburetor was permitted. Mollified, Ford returned in force for 1967 and the arrangement, which ushered in one of the classic eras of motorsport, proved durable, the 427 FE used until 1969 and the 426 HEMI until the big block engines were finally banned after the 1974 season, three years after the last 426 Street HEMI appeared in a showroom.

Among the builders of the big engines used in drag racing (an inventive and occasionally crazy crew) Ed Pink was a revered figure, hinted at by his nickname: “The Old Master”; he lived to 94 and remained active almost to the end, torquing-down the bolts on his last engine at 92. As well as many V8s for drag-racing, Mr Pink also built engines for many other fields in motorsport including NASCAR, Can-Am, and IndyCar but it was those built for the uniquely extreme stresses of ¼ mile runs which most fascinated him. Very much a sport of numbers (time, speed, horsepower), even the highly tuned big-block V8s which might peat at 9000 rpm (crankshaft revolutions per minute) typically will perform only around a thousand of those revolutions between the start and end of the run but the forces being imposed (in many directions) on that large, heavy reciprocating mass are such that catastrophic failures are not uncommon, hence the need for precision in designing, building and maintaining the things.

While the 426 HEMI DOHC never ran (the display unit's valve train was electrically activated), the 427 Cammer was produced for sale in crates and although the number made remains uncertain, most sources suggest it was probably as high as several-hundred and it enjoyed decades of success in various forms of racing including off-shore power boats. Whether it would ever have been reliable in production cars is questionable. Such was Ford’s haste to produce the thing there wasn’t time to develop a proper gear drive system for the various shafts so it ended up with a timing-chain over six feet (1.8m) long. For competition use, where engines are re-built with some frequency, that proved satisfactory but road cars are expected to run for thousands of miles between services and there was concern the tendency of chains to stretch would impair reliability and tellingly, Ford never considered the 427 Cammer for a production car, a breed which, unlike racing engines, attract warranties. Even some sixty years on there’s still a mystique surrounding the cammer and if one can’t find an original for sale (one sold at auction in 2021 for US$60,000), from a variety of manufacturers it’s possible still to buy all the bits and pieces needed to build one (in a quirk of timing and the overlap of simultaneous product development, some of the very early SOHCs used the top oiler block although most were side oilers and the third party reproductions over the years have always been the latter). Although the production numbers have never been verified (which seems strange given Ford's accounting system recorded everything which emerged with a serial number), what all agree is the horsepower of a stock SOHC was somewhere over 600, the number bouncing around a bit because there were versions with single and dual four barrel carburetors, different camshaft profiles and variations in the cylinder heads and while it never made it into a production car, it remains the ultimate FE.