Fork (pronounced fawrk)

(1) An instrument having two or more tines (popularly

called prongs), for holding, lifting, etc., as an implement for handling food

or any of various agricultural tools.

(2) Something resembling or suggesting this in form or

conceptually.

(3) As tuning fork, instruments used (1) in the tuning of

musical instruments and (2) by audiologists and others involved in the study or

treatment of hearing.

(4) In machinery, a type of yoke; a pronged part of any

device.

(5) A generalized description of the division into

branches.

(6) In physical geography and cartography, by

abstraction, the point or part at which a thing, as a river or a road, divides

into branches; any of the branches into which a thing divides (and used by some

as a convention to describe a principal tributary of a river.

(7) In horology, (in a lever escapement) the forked end

of the lever engaging with the ruby pin.

(8) In bicycle & motorcycle design, the support of

the front wheel axles, having the shape of a two-tined fork.

(9) In archery, the barbed head of an arrow.

(10) To pierce, raise, pitch, dig etc, with a fork.

(11) Metonymically (and analogous with the prongs of a

pronged tool), to render something to resemble a fork or describe something using

the shape as a metaphor.

(12) In chess, to maneuver so as to place two opponent's

pieces under simultaneous attack by the same piece (most associated with moves

involving the knight).

(13) In computer programming, to modify a software’s source

code to create a version sufficiently different to be considered a separate path

of development.

(14) To turn as indicated at a fork in a road, path etc.

(15) Figuratively, a point in time when a decision is

taken.

(16) In fulminology (the scientific (as opposed to the artistic or religious) study of lightning), as "forked lightning", the

type of atmospheric discharge of electricity which hits the ground in a bolt.

(17) In software development, content management &

data management, figuratively (by abstraction, from a physical fork), a departure

from having a single source of truth (SSOT) (unintentionally as originally

defined but later also applied where the variation was intentional; metonymically,

any of the instances of software, data sets etc, thus created.

(18) In World War II era British military jargon, the male

crotch, used to indicate the genital area as a point of vulnerability in physical

assault.

(19) in occupational slang, a clipping of forklift; any of

the blades of a forklift (or, in plural, the set of blades), on which the goods

to be raised are loaded.

(20) In saddlery, the upper front brow of a saddle bow,

connected in the tree by the two saddle bars to the cantle on the other end.

(21) In slang, a gallows (obsolete).

(22) As a transitive verb, a euphemistic for “fuck” one

of the variations on f***, ***k etc and used typically to circumvent text-based

filters.

(23) In underground, extractive mining, the bottom of a

sump into which the water of a mine drains; to bale a shaft dry.

(24) As the variant chork, an eating utensil made with a combination of chopstick & fork, intended for neophyte chopstick users.

Pre-1000: From the Middle English forke (digging fork), from the Old English force & forca (pitchfork,

forked instrument, forked weapon; forked instrument used to torture), from the Proto-West

Germanic furkō (fork), from the Latin

furca (pitchfork, forked stake;

gallows, beam, stake, support post, yoke) of uncertain origin. The Middle

English was later reinforced by the Anglo-Norman & Old Northern French forque (it was from the Old French forche which French gained fourche), also from the Latin. It was cognate with the Old Frisian forke, the North Frisian forck (fork), the Dutch vork (fork), the Danish vork (fork) and the German Forke (pitchfork). The evolved Middle English form displaced the native

Old English gafol, ġeafel & ġeafle (fork) (and the apparently

regionally specific forcel (pitchfork)

though the use from circa 1200 to mean “forked stake or post used as a prop

when erecting a gallows” did for a while endure, probably because of the

long-life of the architectural plans for a structure which demanded no change

or functional improvement.

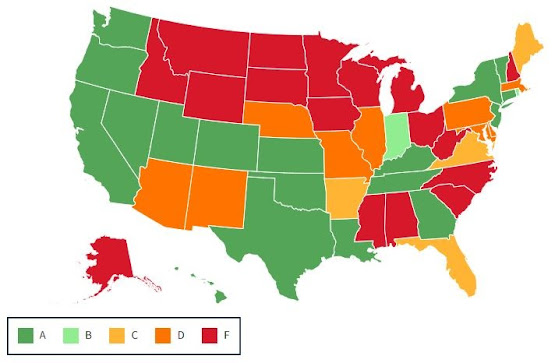

Representation of the forks the Linux operating system. Software forks can extend, die off or merge with other forks.

The forks of The Latin furca (in

its primary sense of “fork”) may be from the primitive Indo-European gherk &

gherg (fork) although etymologists

have never traced any explanation for the addition of the -c-, something which

remains mysterious even if the word was influenced by the Proto-Germanic furkaz

& firkalaz (stake, stick, pole,

post) which was from the primitive Indo-European perg- (pole, post). If such

a link existed, it would relate the word to the Old English forclas pl (bolt), the Old Saxon ferkal (lock, bolt, bar), the Old Norse forkr (pole, staff, stick), the Norwegian

fork (stick, bat) and the Swedish fork (pole). The descendants in other languages include

the Sranan Tongo forku, the Dutch vork, the Japanese フォーク (fōku), the Danish korf, the

Kannada ಫೋರ್ಕ್ (phōrk), the Korean 포크 (pokeu), the Maori paoka,

the Tamil போர்க் (pōrk) and the Telugu ఫోర్క్ (phōrk). In many languages, the previous form was

retained for most purposes while the English fork was adopted in the context of

software development.

Forks can be designed for specific applications, this is a sardine fork, the dimensions dictated by the size of the standard sardine tin.

Although visitors from Western Europe discovered the

novelty of the table fork in Constantinople as early as the eleventh century, the

civilizing influence from Byzantium seems not to have come into use among the English

nobility until the 1400s and the evidence suggest it didn’t come into common use

before the early seventeenth century. The critical moment is said to have come in 1601 when the celebrated traveller and writer Thomas

Coryat (or Coryate) (circa 1577–1617) returned to London from one of his tours, bringing with him the then almost unknown table fork which he'd seen used in Italy. This "continental affectation" made him the subject of mirth and playwrights dubbed him "the fork-carrying traveller" while the street was earthier, the nickname "Furcifer" (from the Latin meaning "fork-bearer, rascal") soon adopted. Mr Coryat thus made one of the great contributions to the niceties of life, his other being the introduction to the English language of the word "umbrella", another influence from Italy.

Cause and effect: The fork in the road.

In Lewis

Carroll’s (1832–1898) Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865), when Alice comes

to a fork in the road, she encounters the Cheshire Cat sitting in a tree:

Alice: “Would

you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?”

Cat: “That

depends a good deal on where you want to get to.”

Alice: “I

don’t know.”

Cat: “Then

it doesn't matter which way you go.”

One can see

the cat’s point and a reductionist like Donald Rumsfeld (1932–2021: US defense

secretary 1975-1977 & 2001-2006) there would have ended the exchange but

the feline proved more helpful, telling Alice she’ll see the Mad Hatter and the

March Hare if she goes in certain directions, implying that no matter which

path she chooses, she’ll encounter strange characters. That she did and the book is one of the most

enjoyable flights of whimsy in English.

The

idiomatic phrase “fork in the road” wasn’t in use early in the seventeenth

century when translators were laboring to create the King James Bible (KJV,

1611) so “…the

king of Babylon so stood at the parting of the way, at the head of the two ways…”

appeared whereas by 1982 when the New King James Version (NKJV, 1982) was

released, that term would have been archaic so the translation was rendered as “…the king of

Babylon stands at the parting of the road, at the fork of the two roads…”.

Ezekiel

21:19-23; King James Version of the Bible (KJV, 1611):

Also, thou

son of man, appoint thee two ways, that the sword of the king of Babylon may

come: both twain shall come forth out of one land: and choose thou a place,

choose it at the head of the way to the city. Appoint a way, that the sword may

come to Rabbath of the Ammonites, and to Judah in Jerusalem the defenced. For the king of Babylon stood at the parting of the way,

at the head of the two ways, to use divination: he made his arrows

bright, he consulted with images, he looked in the liver. At his right hand was

the divination for Jerusalem, to appoint captains, to open the mouth in the

slaughter, to lift up the voice with shouting, to appoint battering rams

against the gates, to cast a mount, and to build a fort. And it shall be unto

them as a false divination in their sight, to them that have sworn oaths: but

he will call to remembrance the iniquity, that they may be taken.

Ezekiel

21:19-23; New King James Version of the Bible (NKJV, 1982):

And son of

man, appoint for yourself two ways for the sword of the king of Babylon to go;

both of them shall go from the same land. Make a sign; put it at the head of

the road to the city. Appoint a road for the sword to go to Rabbah of the

Ammonites, and to Judah, into fortified Jerusalem. For

the king of Babylon stands at the parting of the road, at the fork of the two

roads, to use divination: he shakes the arrows, he consults the images,

he looks at the liver. In his right hand is the divination for Jerusalem: to

set up battering rams, to call for a slaughter, to lift the voice with

shouting, to set battering rams against the gates, to heap up a siege mound,

and to build a wall. And it will be to them like a false divination in the eyes

of those who have sworn oaths with them; but he will bring their iniquity to

remembrance, that they may be taken.

The KJV

& NKJV closely are related but do in detail differ in the language used,

the objective of the latter being to enhance readability while retaining the stylistic

beauty and literary structure of the original.

Most obviously, the NKJV abandoned the use of archaic words and convention

of grammar (thee, thou, ye, thy, thine, doeth, speaketh etc) which can make it difficult

for modern readers to understand, rather as students can struggle with

Shakespeare’s text, something not helped by lecturers reminding them of its

beauty, a quality which often escapes the young. The NKJV emerged from a reaction to some of

the twentieth century translations which traditionalist readers thought had “descended”

too far into everyday language; it was thus a compromise between greater

readability and a preservation of the original tone. Both the KJV & NKJV primarily used the Textus Receptus (received text) for the

New Testament and Masoretic Text for the Old Testament and this approach

differed from other modern translations (such as the New International Version

(NIV, 1978) & English Standard Version (ESV, which 2001) used a wider

sub-set of manuscripts, including older ones like the Alexandrian texts (Codex

Vaticanus, Sinaiticus etc) So, the NKJV

is more “traditional” than modern translations but not as old-fashioned as the

KJV and helpfully, unlike the KJV which provided hardly any footnotes about

textual variants, the NKJV was generous, showing where differences existed

between the major manuscript traditions (Textus Receptus, Alexandrian &

Byzantine), a welcome layer of transparency but importantly, both used a formal

equivalence (word-for-word) approach which put a premium on direct translation

over paraphrasing, the latter technique much criticized in the later

translations.

Historians

of food note word seems first to have appeared in this context of eating utensils in an inventory of

household goods from 1430 and they suggest, because their influence in culinary

matters was strongest, it was probably from the Old North French forque.

It came to be applied to rivers from 1753 and of roads by 1839. The use in bicycle design began in 1871 and

this was adopted directly within twenty years when the first motorcycles

appeared. The chess move was first so-described

in the 1650s while the old slang, forks "the two forefingers" was

from 1812 and endures to this day as “the fork”. In the world of cryptocurrencies, fork has

been adopted with fetish-like enthusiasm to refer to (1) a split in the blockchain

resulting from protocol disagreements, or (2) a branch of the blockchain

resulting from such a split.

Lindsay Lohan with Tiramisu and cake-fork, Terry Richardson (b 1965) photoshoot, 2012.

The verb dates from the early fourteenth century in the

sense of (1) “to divide in branches, go separate ways" & (2) "disagree,

be inconsistent", both derived from the noun. The transitive meaning "raise or pitch

with a fork" is from 1812, used most frequently in the forms forked & forking

while the slang verb phrase “fork (something) over” is from 1839 while “fork

out” (give over) is from 1831). The now

obsolete legal slang “forking” in the forensic sense of a "disagreement

among witnesses" dates from the turn of the fifteenth century. The noun forkful was an agricultural term

from the 1640s while the specialized fourchette

(in reference to anatomical structures, from French fourchette (diminutive of fourche

(a fork)) was from 1754. The noun pitchfork

(fork for lifting and pitching hay etc.) described the long-used implement

constructed commonly with a long handle and two or three prongs first in the

mid fourteenth century, altered (by the influence of pichen (to throw, thrust), from the early thirteenth century Middle

English pic-forken, from pik (source of pike). The verb use meaning "to lift or throw

with a pitchfork," is noted from 1837.

The spork, an eating utensil which was fashioned by making several long

indents in the bowl to create prongs debuted in 1909.

Der Gableschwanz Teufl: The Lockheed P-38 Lightning (1939-1945). During World War II (1939-1945), the Luftwaffe’s (German air force) military slang for the twin-boomed Lockheed P-38 Lightning was Der Gableschwanz Teufl (the fork-tailed devil).

Novelty nail-art by US

restaurant chain Denny's. The manicure

uses as a base a clean, white coat of lacquer, to which was added miniature

plastic utensils, the index finger a fork, the middle finger a knife, the ring

finger a spoon, and the pinky finger presumably a toothpick or it could be

something more kinky.

The idiomatic “speak with forked tongue” to indicate duplicitous

speech dates from 1885 and was an invention of US English though reputedly

influenced by phases settlers learned in their interactions with first nations

peoples (then called “Red Indians”). The

earlier “double tongue” (a la “two-faced”) in the same sense was from the

fifteenth century. Fork as a clipping of

the already truncated fork-lift (1953) fom the fork-lift truck (1946), appears

to have enter the vernacular circa 1994.

The adjective forked (branched or divided in two parts) was the past-participle

adjective from the verb and came into use early in the fourteenth century. It was applied to roads in the 1520s and more

generally within thirty years while the use in the sixteenth and seventeenth

century with a suggestion of "cuckold" (on the notion of "horned")

is long obsolete. Applied in many contexts (literally & figuratively), inventions (with and without hyphens) include fork-bomb, fork-buffet, fork-dinner, fork-head, rolling-fork, fork-over, fork-off & fork-up (the latter pair euphemistic substitutions for "fuck off" & "fuck-up).

Spork from a flatware set made for Adolf Hitler's

(1889-1945; German head of government 1933-1945 & head of state 1934-1945)

fiftieth birthday, sold at auction in 2018 for £12,500. The items had been discovered in England in a

house once owned by a senior military officer, the assumption being they were

looted in 1945 (“souveniring” in soldier's parlance), the items all bearing the Nazi eagle, swastika

and Hitler's initials. Auction houses can be inconsistent in their descriptions of sporks and in some cases they're listed as splayds, the designs sometimes meaning it's a fine distinction.

1979

Benelli 750 Sei (left) and Benelli factory schematic of the 750 Sei’s fork

(series 2a, right).

One quirk

in the use of the word is the tendency of motorcyclists to refer to the front

fork as “the forks”. Used on almost every

motorcycle made, the fork is an assembly which connects the front axle (and

thus the wheel) to the frame, usually by via a pair (upper & lower) of

yokes; the fork provides both the front suspension (springs or hydraulics) and

makes possible the steering. The reason

the apparatus is often called “the forks” is the two most obvious components

(the left & right) tubes appear to be separate when really they are two

prongs connected at the top. Thus, a

motor cycle manufacturer describes the assembly (made of many components (clamp,

tubes, legs, springs, dampers etc)) “a fork” but, because of the appearance,

riders often think of them as a pair of forks, thus the vernacular “the forks”. English does have other examples of such

apparent aberrations such as a “pair of spectacles” which is sold as a single

item but the origin of eye-glasses was in products sold as separate lens and

users would (according to need) buy one glass (what became the monocle) or a pair

of glasses. That is a different structural

creation than the bra which on the model of a “pair of glasses” would be a “pair

of something” but the word is a clipping of “brassiere”. English borrowed brassiere from the French brassière, from the Old French braciere (which was originally a lining

fitted inside armor which protected the arm, only later becoming a garment),

from the Old French brace (arm)

although by then it described a chemise (a kind of undershirt) but in the US,

brassiere was used from 1893 when the first bras were advertised and from

there, use spread. The three syllables

were just too much to survive the onslaught of modernity and the truncated

“bra” soon prevailed, being the standard form throughout the English-speaking

world by the early 1930s. Curiously, in

French, a bra is a soutien-gorge

which translates literally and rather un-romantically as “throat-supporter”

although “chest uplifter” is a better translation.

2004 Dodge Tomahawk.

There have been variations on the classic

fork and even designs which don’t use a conventional front fork, most of which

have been variations on the “swinging arm” a structure which is either is or

tends towards the horizontal. One of the

most memorable to use swinging arms was the 2004 Dodge Tomahawk, a “motorcycle”

constructed around a 506 cubic inch (8.3 litre) version of the V10s used in the

Dodge Viper (1991-2010 & 2013-2017) and the concept demonstrated what

imaginative engineers can do if given time, money, resources and a

disconnection from reality, Designing a 500

HP (370 kW) motorcycle obviously takes some thought so what they did to

equalize things a bit in what would otherwise be an unequal battle with physics

was use four independently sprung wheels which allowed the machine to corner with

a lean (up to 45o said to be possible) although no photographs seem

to exist of an intrepid rider putting this projection to the test. Rather than a fork, swinging arms were used

and while this presumably enhanced high-speed stability, it also meant the

turning circle was something like that of one of the smaller aircraft carriers. There were suggestions a top speed of some 420

mph (675 km/h) was at least theoretically possible although a sense of reality

did briefly intrude and this was later revised to 250 mph (400 km/h). In the Dodge design office, presumably it was thought safe to speculate

because of the improbability of finding anyone both sufficient competent and

crazy enough to explore the limits; one would plenty of either but the characteristics rarely co-exist.

Remarkably, as many as ten replicas were sold at a reputed US$555,000

and although (mindful of the country’s litigious habits) all were non-operative

and described as “art deco inspired automotive sculpture” to be admired as

static displays, some apparently have been converted to full functionality

although there have been no reports of top speed testing.

Britney Spears (b 1981): "Video clip with fork feature", Instagram, 11 May 2025.

Unfortunately, quickly Ms Spears deleted the more revealing version of the clip but for those pondering

the messaging, Spearologists (a thoughtful crew devoted to their discipline)

deconstructed the content, noting it came some days after she revealed it had

been four months she’d left her house.

The silky, strapless dress and sweat-soaked, convulsing flesh were (by

her standards) uncontroversial but what may have mystified non-devotees was the fork

she at times held in her grasp.

Apparently, the fork was an allusion to her earlier quote: “Shit! Now I have to find my FORK!!!”, made

during what was reported as a “manic meltdown” (itself interesting in that it at least suggests the existence of “non-manic” meltdowns) at a restaurant, following

the abrupt departure of her former husband (2022-2024) Hesam "Sam"

Asghari (b 1994). The link between restaurant

and video clip was reports Mr Asghari was soon to be interviewed and there would

be questions about the marriage. One of her earlier posts had included a fork stabbing a lipstick (forks smeared with lipstick a trick also used in Halloween costuming to emulate facial scratches) and the utensil in the clip was said to be “a symbol of her frustration and emotional state.” Now we know.

Großadmiral

(Grand Admiral, equivalent to an admiral of the fleet (Royal Navy) or five star

admiral (US Navy) Alfred von Tirpitz (1849–1930; State Secretary of the German

Imperial Naval Office 1897-1916).

He's

remembered now for (1) his role in building up the Imperial German Navy, triggering events

which would play some part in the coming of World War I (1914-1918) and (2) being

the namesake for the Bismarck class battleship Tirpitz (1939-1944) which although it hardly

ever took to the high seas and fired barely a shot in anger, merely by being

moored in Norwegian fjords, it compelled the British Admiralty to watch it with

a mix of awe and dread, necessitating keeping in home waters a number of

warships badly needed elsewhere. He’s remembered also for (3) his distinctive twin-forked beard and such was the threat his namesake battleship represented, just the mistaken belief she was steaming into

the path of a convoy (PQ 17, June 1942) of merchant ships bound for the Russian port of Archangel caused the Admiralty to issue a “scatter order” (ie disperse the convoy from the escorting warships), resulting in heavy losses.

After a number of attempts, in 1944, she

was finally sunk in a raid by Royal Air Force (RAF) bombers although, because some of the capsized hull remained visible above the surface, some wags in the navy insisted the air force had not "sunk the beast" but merely "lowered her to the waterline". It wasn't until after the war the British learned the RAF's successful mission, strategically, had been unnecessary, earlier attacks (including the Admiralty's using mines placed by crews in midget submarines) having inflicted so much damage there was by 1944 no prospect of the Tirpitz again venturing far from its moorings.

Lieutenant

General Nagaoka Gaishi san, Tokyo, 1920.

When Großadmiral von Tirpitz died in

1930, he and twin-fork beard were, in the one casket, buried in Bavaria's

Münchner Waldfriedhof “woodland cemetery”.

The “one body = one casket” protocol is of course the almost universal practice

but there have been exceptions and one was Lieutenant General Gaishi Nagaoka

(1858-1933) who served in the Imperial Japanese Army between 1978-1908, and was

vice chief of the general staff during the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). While serving as a military instructor, one

of his students was the future Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek (1887-1975; leader

of the Republic of China (mainland) 1928-1949 & the renegade province of

Taiwan 1949-1975), After retiring from

the military, he entered politics, elected in 1924 as a member of the House of

Representatives (after Japan in the 1850s ended its “isolation” policy, it’s

political and social system were a mix of Japanese, British and US

influences). After he died in 1933, by explicit

request, his impressive “handlebar” moustache carefully was removed and buried in

a separate casket in Aoyama Cemetery.