Flatware (pronounced flat-wair)

In catering, an omnibus term covering (1) cutlery such as

the knives, forks, and spoons used at the table for serving and eating food

& (2) crockery such as those plates, saucers, dishes or containers which tend

to flatness in shape (as opposed to the more capacious hollowware).

1851: The construct was flat + ware. Flat dates from 1275–1325 and was from the

Middle English flat from the Old

Norse flatr, related to Old High

German flaz (flat) and the Old Saxon flat (flat; shallow) and akin to Old

English flet. It was cognate with the Norwegian and Swedish

flat and the Danish flad, both from the Proto-Germanic flataz, from the primitive Indo-European

pleth (flat); akin to the Saterland

Frisian flot (smooth), the German

flöz (a geological layer), the Latvian plats and Sanskrit प्रथस् (prathas)

(extension). Source is thought to be the

Ancient Greek πλατύς (platús & platys)

(flat, broad). The sense of

"prosaic or dull" emerged in the 1570s and was first applied to drink

from circa 1600, a meaning extended to musical notes in the 1590s (ie the tone

is "lowered"). Flat-out, an

adjectival form, was first noted in 1932, apparently a reference to pushing a

car’s throttle (accelerator) flat to the floor and thus came to be slang for a

vehicle’s top speed. The noun was from

the Middle English flat (level piece

of ground, flat edge of a weapon) and developed from the adjective; the US

colloquial use as a noun from 1870 meaning "total failure" endures in

the sense of “falling flat”. The notion

of a small, residential space, a divided part of a larger structure, dates from

1795–1805; variant of the obsolete Old English flet (floor, house, hall), most suggesting the meaning followed the

early practice of sub-dividing buildings within levels. In this sense, the Old High German flezzi (floor) has been noted and it is

perhaps derived from the primitive Indo-European plat (to spread) but the link to flat as part of a building is

tenuous.

Ware was from the Middle English ware & war, from the Old English waru & wær (article of merchandise (originally “protection, guard”, the sense probably derived from “an object of care, that which is kept in custody”), from the Proto-Germanic warō & Proto-West Germanic war, from the Proto-Germanic waraz, the Germanic root also the source of the Swedish vara, the Danish vare, the Old Frisian were, the Middle Dutch were, the Dutch waar, the Middle High German & German Ware (goods). All ultimately were from the primitive Indo-European root wer- (perceive, watch out for) In Middle English, the meaning shifted from "guard, protection" to "an object that is in possession, hence meriting attention, guarded, cared for, and protected". Thus as a suffix, -ware is used to form nouns denoting, collectively, items made from a particular substance or of a particular kind or for a particular use. In the special case of items worn as clothing, the suffix -wear is appended, thus there is footwear rather than footware. In the suffixed form, ware is almost always in the singular but as a stand-alone word (meaning goods or products etc), it’s used as wares. Ladyware was a seventeenth century euphemism for "a woman's private parts" (the companion manware etc much less common) and in Middle English there was also the mid-thirteenth century ape-ware (deceptive or false ware; trickery). Flatware is a noun; the noun plural is flatwares.

Hardware and software were adopted by the

computer industry, the former used from the very dawn of the business in the

late 1940s, borrowing from the mid-fifteenth century use which initially

described “small metal goods” before evolving to be applied to just about

everything in building & construction from tools to fastenings. Apparently, software didn’t come into use

until the 1960s and then as something based on “hardware” rather than anything

to do with the mid-nineteenth century use when it described both "woolen

or cotton fabrics" and "relatively perishable consumer goods";

until then there was hardware & programs (the term “code” came later). The ecosystem spawned by the industry picked

up the idea in the 1980s, coining shareware (originally software distributed

for free for which some payment was hoped) and that started a trend, begetting:

Abandonware: Software no longer updated or maintained, or

on which copyright is no longer defended or which is no longer sold or

supported; such software can, with approval, pass to others for development

(takeoverware) or simply be purloined (hijackware). Abandonware is notoriously associated with

video game development where there’s a high failure rate and many unsuccessful

projects later emerge as shareware or freeware.

Adware: Nominally free software which includes

advertising while running. Adware sometimes

permits the advertising to disappear upon payment and is popularly associated

with spyware although the extent of this has never reliably been quantified.

Baitware: Software with the most desirable or tempting

features disabled but able to be activated upon payment; a type of crippleware

or demoware.

Freeware: Free software, a variation of which is “open

source” which makes available also the source code which anyone may modify and

re-distribute on a non-commercial basis.

Google’s Chrome browser is a famous example, developed from the open

source Chromium project.

Censorware: An umbrella term for content-filtering

software.

Demoware: A variation of crippleware or baitware in that

it’s a fully-functional version of the software but limited in some critical way

(eg ceases to work after 30 days); also called trialware. The full feature set is unlocked by making a payment which ensures the user is provided with a code (or "key") to activate full-functionality. The fashionable term for this approach is "freemium" (a portmanteau of free & premium, the idea being the premium features cost something.

Donationware: Pure shareware in that it’s

fully-functional and may be used without payment but donations are requested to

support further development. A type of

shareware.

Postcardware: Developer requests a postcard from the user’s

home town. This really is a thing and

the phenomenon is probably best explained by those from the behavioral science

community; also called cardware.

Ransomware: Software which “locks” or in some way renders

inaccessible a user’s data or system, requiring a payment (usually in

crypto-currency) before access can be regained; malware’s growth industry.

Spyware: Software which furtively monitors a user’s actions,

usually to steal and transmit data; antispyware is its intended nemesis.

Malware: Software with some malicious purpose including

spyware and ransomware.

Bloatware: Either (1) the programs bundled by

manufacturers or retailers with devices when sold, (often trialware and in some

notorious cases spyware) or (2) software laden with pointless “features” nobody

will ever use; also called fatware, fattware and phatware.

Vaporware: Non-existent software which is either well behind schedule or has only ever been speculative; also called noware.

Flat as a noun, prefix or adjective has also been productive: Flat white can be either a coffee or a non-gloss paint. Flatway and flatwise (with a flat side down or otherwise in contact with a flat surface) are synonymous terms describing the relationship of one or more flat objects in relation to others and flat-water is a nautical term meaning much the same as "still-water". The flat universe is a cluster of variations of one theory among a number of speculative descriptions of the topological or geometric attributes of the universe. Probably baffling to all but a few cosmologists, the models appear suggest a structure which include curves while as a totality being of zero curvature and, depending on the detail, imply a universe which either finite or infinite.

The “going flat” movement describes an activist community of women who have undergone a mastectomy (the surgical removal of one breast (unilateral or single) or both (bilateral or double)) who elect not to undergo a reconstruction. Since reconstructive surgery became mainstream in the 1980s, a large percentage of women who had a mastectomy opted (for whatever reason) not to reconstruct but the more recent “going flat” movement was a political act: a reaction against what is described in the US as the “medical-industrial complex”, the point being that women who have undergone a mastectomy should not be subject to pressure either to use an external prosthetic (usually placed in a "pocketed" mastectomy bra) or agree to surgical reconstruction (a lucrative procedure for the industry). It’s a form of advocacy which has a focus not only on available fashions but also the need for a protocol under which, if women request an AFC (aesthetic flat closure, a surgical closure (sewing up) in which the “surplus” skin, often preserved to accommodate a future reconstructive procedure, is removed and the chest rendered essentially “flat”), that is what must be provided. The medical industry has argued the AFC can preclude a satisfactory cosmetic outcome in reconstruction if a woman “changes her mind” but the movement insists it's an example of how the “informed consent” of women is not being respected. Essentially, what the “going flat” movement seems to be arguing is the request for an AFC should be understood as an example of the legal principle of VAR (voluntary assumption of risk). The attitude of surgeons who decline to perform an AFC is described by the movement as the “flat refusal”.

Iron Flatheads: Ford flathead V8 with heads removed (right), a pair of (flat) heads (centre) and flathead V8 with (aftermarket Offenhauser) heads installed.

In internal combustion engines, a flathead engine (also called the side-valve or L-Head) is one where the poppet valves are built into the engine block rather than being in a separate cylinder head which has since the 1950s been the almost universal practice (overhead valve (OHV) and overhead camshaft (OHC)). Until the 1950s, flatheads were widely available in both cheap and expensive vehicles because they used relatively few moving parts, were simple (and thus economic) to manufacture and existed in an era of low-octane fuels which tended to preclude high engine speeds. During World War II (1939-1945), what would otherwise have taken decades of advances in design and metallurgy was accomplished in five years and flathead designs mostly were phased out of production except for non-automotive niches where simple, cheap, low-revving units were ideal. The classic flathead was the Ford V8 (1932-1953 in the US market although, remarkably, production overseas didn’t end until 1993!) which encompasses all the advantages and disadvantages of the design and was so identified with the concept that it’s still known as “the Flathead”, the name gained because the “head”, containing no valve-gear or other machinery, is little more than a piece of flat steel providing a sealing for the combustion process.

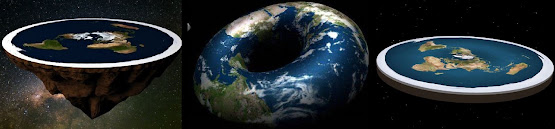

Flat Earth Society factional options: conical (left), doughnut (centre) & disk (right), the latter enjoying the greatest support among the flat-Earthers.

Members of the Flat Earth Society believe the Earth is flat but there's genuine debate within the organization, some holding the shape is disk-like, others that it's conical but both agree we live on something like the face of a coin. There are also those in a radical faction suggesting it's actually shaped like a doughnut but this theory is regarded by the flat-earth mainstream worse than speculative, the proponents branded as heretics. Evidence, such as photographs from orbit showing Earth to be spherical, is dismissed as part of the "round Earth conspiracy" run by NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration), the Freemasons and subversives like the Secret Society of the Les Clefs d'Or. The flat-earther theory is the Arctic Circle lies in the centre with the Antarctic a 150-foot (45m) tall wall of ice around the rim; NASA contractors guard the ice wall so nobody look over the edge and thus disprove the "round Earth lie". Cosmologically, Earth's daily cycle is a product of the Sun & Moon being 32 mile (51 km) wide spheres travelling in a plane 3,000 miles (4,800 km) above Earth while the more distant stars are some 3100 miles (5000 km) away and there's also an invisible "anti-moon" which obscures the "real Moon" during lunar eclipses. Explained like that, it all sounds plausible so the flat-earthers may be onto something the deep state long has hidden from us.

Ballet flats are shoes which either literally are or closely resemble a ballerina’s dancing slippers. In the US, ballet flats are almost always called ballet pumps and this use has spread, many in the industry also now calling them pumps, presumably just for administrative simplicity although the standardization does create problems because the term “pump” is used to describe a wide range of styles and there’s much inconsistency between markets. A flat-file database is a database management system (DBMS) where records are stored in a uniform format with no structure for indexing or recognizing relationships between entries. A flat-file database is best visualized as the page of a spreadsheet with no capacity for three-dimensionality but, in principle, there’s no reason why a flat-file database can’t be huge although they tend for many reasons not to be suitable to use at scale.

The Flatiron, NY - Evening, 1905, photograph by Edward Steichen (1879-1973) (left) and The Flatiron building (circa 1904) oil on canvas by Ernest Lawson (1873-1939) (right).

Opened in 1902, the Flatiron Building is a 22 storey, 285 foot (86.9 m) tall building with a triangular footprint, located at 175 Fifth Avenue in what is now called the Flatiron District of Manhattan in New York City. Originally called the “Fuller Building” (named after the construction company which owned the site), the Flatiron was one of the city’s first skyscrapers and gained the nickname which stuck because people compare the shape to the cast-iron clothes irons then on sale and even while being built it was recognized as a striking design and remains an example of what would early in the twentieth century come to be called "modernist architecture"; it was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1989.

The comparison with the household iron was understandable but when viewed from ground level, the shape is deceptive; whereas an iron is symmetrical, the Flatiron is an irregular triangle, a wedge shape which in a number of fields (including geometry, landscape architecture & civil engineering) is sometimes called a "spandrel triangle" but the term seems not widely used by architects who prefer the more encompassing "irregular triangle" (ie one not equilateral or isosceles) or just the pleasingly brutish "wedge". Among architects (and especially critics of the discipline) however, "flatiron" has become a quasi-technical and in colloquial use structures with similar wedge-shaped forms are often referred to as "flatiron buildings".

Flatware

Flatware in its historic sense is now rarely used outside

of the categorization systems of catering suppliers except in the US where it

vies with “silverware” and the clumsy “flatwaresilverware” to describe what is in most of

the English-speaking world called cutlery.

In modern use, a term which covers some utensils and some dishware seems

to make no sense and that’s correct. The

origin of flatware belongs to a time when those to whom an invitation to dinner

was extended would bring their own “flatware” (knife, fork, spoon, plate, goblet) because

in most houses, those items existed in numbers sufficient only for the inhabitants.

As applied to crockery, flatware items were in the

fourteenth century those plates, dishes, saucers which were "shallow &

smooth-surfaced", distinguishing them from hollowware which were the

larger items (steel, china, earthenware) of crockery used to cook or serve food

(onto or into flatware to be eaten with flatware). The seemingly aberrant case of the cup (something

inherently hollow) being flatware is that what we would now call a mug or

goblet, like a knife, fork or plate, was an item most people would carry with

them when going to eat in another place.

The issue of cup and saucer existing in different categories thus didn’t

exist and in any case saucers were, as the name suggests, originally associated

with the serving of sauce, being a drip-tray.

The cup and saucer in its modern form didn’t appear until the mid

eighteenth century when a handle was added to the little bowls which had been

in use in the West for more than a hundred years (centuries earlier in the

East) and reflecting handle-less age, the phrase “a dish of tea” is still an occasionally

heard affectation.

Elizabeth II (1926-2022; Queen of the UK and other places, 1952-2022) bidding farewell to Bill Clinton (b 1946; US president 1993-2001) & crooked Hillary Clinton (b 1947; US secretary of state 2009-2013), Buckingham Palace, 2000.

Almost universally, flatware is referred to as "the silver". Eating and drinking has long been fetishized and adopted increasingly elaborate forms of service so (except for the specific sense in the US) the term flatware is now of little use outside the databases of catering suppliers, crockery and cutlery now more useful general categories which can accommodate what is now a huge number of classes of wares.