Synod (pronounced sin-uhd)

(1) An assembly of ecclesiastics or other church

delegates (particularly of a diocese), convoked pursuant to the law of the

church, for the discussion and decision of ecclesiastical affairs (in various denominations

such gatherings sometimes described as ecclesiastical councils or).

(2) An assembly or council having civil authority; a

legislative body and used (sometimes loosely) of any council of any institution

(in this context also used disparagingly of secular institutions thought

becoming too rigid in thought or process.

(3) An (often geographical) administrative division or

district in the structures of some churches, either the entire denomination or

a mid-level division such as a “middle judicatory” or “district”); use of the

word “synod” differs between and sometimes within denominations.

(4) In astronomy, a conjunction of two or more of the

heavenly bodies.

1350–1400: From the Middle English synod (ecclesiastical council), from the Late Latin synodus, From the Ancient Greek σύνοδος

(súnodos or sýnodos) (assembly, meeting; a coming together, a conjunction of

planets), the construct being the English syn-(from

the Ancient Greek σύν (sún) (with, in

company with, together with) + ὁδός ((h)odós) (traveling,

journeying; a manner or system (of doing, speaking, etc.); a way, road, path

(the word of uncertain origin). The term

סַנְהֶדְרִין (sunédrion) exists in the Hebrew

Talmudic literature and was used in a similar way and the early twelfth century

Middle English form was sinoth. Synod was used in the Presbyterian Church

between 1953-1922 in the traditional sense of “an assembly of ministers and

other elders” when the term was changed to “General Council”, an act of

modernization apparently provoked by the word “synod” beings so associated with

the Roman Catholic Church and the Church of England. In the schismatic world of the Medieval

Church, just as there were from time to time, “antipopes” (from the Medieval

Latin antipāpa), there were also

antisynods, convened as meetings of his supporters. Synod and synodicon are nouns, synodic is an

adjective, synodal is a noun & adjective, the noun plural is synods.

The adjective synodal (of or relating to a synod) was a

mid-fifteenth century creation from the Late Latin synodalis. As a noun, a synodal

was (1) a constitution made in a provincial or diocesan synod which was subject

to review by a central body or (2) a tribute in money formerly paid to the

bishop or archdeacon (at the time of his Easter visitation), by every parish

priest (now made to the ecclesiastical commissioners and in later versions of canon

law referred to as a "procuration"). The

adjective synodic dates from the 1630s and was from the Latin synodicus, from the Ancient Greek

συνοδικός (sunodikós) (of or related

to an assembly or meeting); the form used in the late sixteenth century was synodical. When used of the conjunction of two or more

of the heavenly bodies (the moon and the planets) described by the astronomers

of Antiquity, the phenomenon may be called a “synodical revolution” and the

time in which it occurs a “synodical month”. Despite sounding suspiciously

modern, a synodicon is not associated with on-line video gaming. The noun synodicon was from the Latin, from

the Ancient Greek συνοδικόν (sunodikón)

and was a substantivisation of συνοδικός (sunodikós)

(synodical). Institutionalized in modern

Italianate Ecclesiastical Latin, it describes a document from a church synod or

synods, especially the official records of proceedings. A subsynod (sometimes as sub-synod) is either

(1) an assembly of officials which meets prior to a synod proper to make

administrative arrangements, formalize an agenda etc or (2) a kind of sub-committee

of a synod which is created for some purpose such as allowing a technical

matter to be discussed by experts before being referred to the full assembly of the synod for

deliberation.

The noun synodality (the plural synodalities) is used in Christianity

to refer (sometimes perhaps optimistically) to the “quality or style of a

synod; the fraternal collaboration and discernment as typified in a synod”. The origin of the word synod (the Ancient

Greek συν (together) + ὁδός (journey) hints at the

hopefully fraternal collaboration and discernment that such gatherings of

ecclesiastical worthies are intended to be, the expression of this the

essence of synodality. The notion of synodality

is a part of the mystique of the Roman Catholic Church because it’s said to denote

the essence of the church’s mission, something explained by the Holy See's

International Theological Commission (ITC) which states that synodality encapsulates

“the specific modus vivendi et operandi (way

of living & method of operation) of the Church, the People of God, which

reveals and gives substance to her being as communion when all her members

journey together, gather in assembly and take an active part in her evangelizing

mission”.

The ITC is an organization of the Roman Curia which advises

the magisterium of the church, most notably the Dicastery for the Doctrine of

the Faith (DDF, the old Holy Office which many still refer to by its original

name: The Inquisition). The IDF was a

creation of the re-structuring in the wake of the Second Vatican Council (Vatican

II; 1962-1965) and formerly was established in 1969 as a kind of internal think

tank which might present a kinder face to the world than the rather austere Congregation

for the Doctrine of the Faith (the CDF (as the DDF was then known)). That was an approach not unknown (for good

& bad) in secular politics and while over the years there have been those

who claimed the relationship between the ITC and the CDF was the sort of “creative

tension” needed to ensure debates over matters of ethics and procedure stayed

dynamic, others have seen the tension but little creativity. For students of structuralism, it’s of

interest the prefect of the DDF is ex

officio the president of the ITC, an arrangement carried over in June 2022

when Pope Francis (b 1936; pope since 2013), as a part of a range of reforms to

the curia, announced the name change from CDF to DDF.

Pope Francis has made synodality (at least his conception

of it) as perhaps the core value he intends to be the legacy of his pontificate

and the ITC in 2018 published a paper which made explicit Francis was not

modest in his ambitions for that legacy, the ITC’s document stating it was “…precisely

this path of synodality which God expects of the Church of the third

millennium” and stressed synodality “…is an essential dimension of the Church”,

in the sense that “what the Lord is asking of us is already in some sense

present in the very word 'synod’”.

Although presumably the pope and the ITC were more concerned with

theology than etymology, tracing a tread which ran from the gathering of Christ’s

disciples to the sessions of Vatican II in the 1960s, word nerds would anyway

have enjoyed the thoughts:

In ecclesiastical Greek it

expresses how the disciples of Jesus were called together as an assembly and in

some cases it is a synonym for the ecclesial community. Saint John Chrysostom,

for example, writes that the Church is a “name standing for 'walking together’

(σύνοδος)". He explains that the Church is actually the assembly convoked

to give God thanks and glory like a choir, a harmonic reality which holds

everything together (σύστημα), since, by their reciprocal and ordered

relations, those who compose it converge in αγάπη and όμονοία (common mind).

Since the first centuries,

the word “synod” has been applied, with a specific meaning, to the ecclesial

assemblies convoked on various levels (diocesan, provincial, regional,

patriarchal or universal) to discern, by the light of the Word of God and

listening to the Holy Spirit, the doctrinal, liturgical, canonical and pastoral

questions that arise as time goes by.

The Greek σύνοδος is

translated into Latin as synodus or concilium. Concilium, in its profane use,

refers to an assembly convoked by some legitimate authority. Although the roots

of “synod” and “council” are different, their meanings converge. In fact,

“council” enriches the semantic content of “synod” by its reference to the

Hebrew קָהָל(qahal), the assembly convoked by the Lord, and its

translation into Greek as έκκλησία, which, in the New Testament, refers to the

eschatological convocation of the People of God in Christ Jesus.

In the Catholic Church the

distinction between the use of the words “council” and “synod” is a recent one.

In Vatican II they are synonymous, both referring to the council session. A

precise distinction was introduced by the Codex Iuris Canonici of the Latin

Church (1983), which distinguishes between a particular (plenary or provincial)

Council and an ecumenical Council on the one hand, and a Synod of Bishops and a

diocesan Synod on the other hand.

5. In the theological,

canonical and pastoral literature of recent decades, a neologism has appeared,

the noun “synodality”, a correlate of the adjective “synodal”, with both of

these deriving from the word “synod”. Thus people speak of synodality as a

“constitutive dimension” of the Church or tout court of the “synodal Church”.

This linguistic novelty, which needs careful theological clarification, is a

sign of something new that has been maturing in the ecclesial consciousness

starting from the Magisterium of Vatican II, and from the lived experience of

local Churches and the universal Church since the last Council until today.

So for Francis, the word synodality has assumed an

importance beyond that with which it has so long been vested in the Catholic

Church so the Vatican watchers took note when, under the pope’s imprimatur, it

was in October 2021 announced a summit to be conducted over two years was

to be known as the Synod on Synodality.

It would have sounded an innocuous thing had it not been for the ITC’s

paper three years earlier and it had the inevitable immediate effect among the

clergy, the laity and the theologians: sniffing change in the air, some were

hopeful and some fearful. However, the

pope, although thought by many a disruptor is also a realist and understands

change in his 2000 year old institution will unfold among the generations to

come and his immediate ambition seems restricted to tweaking the way the church

relates to the rest of the world rather than overturning dogma. Thus, expectations of welcoming the LGBTQQIAAOP

in the church or approving the ordination of women are absurd but there may be

changes in the way bishops both interact with their flock and the priests who

are closer to that flock. Just because a

change doesn’t happen in the corridors of the Vatican where the curia plot and

scheme, doesn’t mean the power structures haven’t changed. The flock doesn’t mix with the curia; they

talk to their parish priest.

Interestingly, for something some fear will be the

harbinger of something radical, the Synod on Synodality is structured in the

traditional (Vatican II style) modules with un-threatening names like "communion", "mission" & "participation" but however vague may be the indication of the

content, few doubt that at the next session the factions will be mapping onto

those titles the concerns which have for decades troubled Rome and it’ll be

mostly about sex: whether the thousand-year enforcement of clerical celibacy is

the underlying cause of the rampant child-sex abuse among its members, the role

of women in the power structures and attitudes towards same-sex relationships

including marriage. Those discussions

will play out between the factions and there are few with any hope there'll be many

minds changed but the tone of the synod will be important and Francis has the

advantage of being the absolute monarch in a theocracy; it is Francis who gets

to review the synodicon the theologians and the bishops will submit and he will

write the final document of the Synod on Synodality.

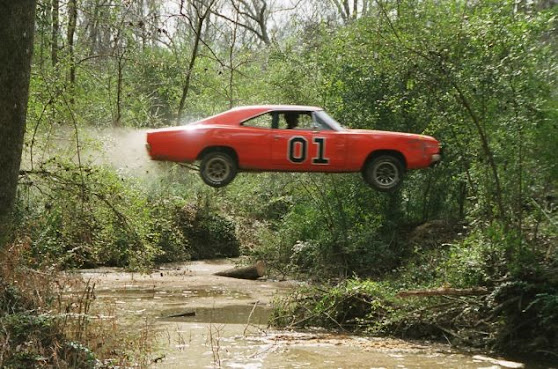

Working for more synodality in the world: Lindsay Lohan supporting the NOH8 campaign which sought to end California's 2008 voter-approved gay marriage ban (Proposition 8).

It means Francis has immense power to shape things and point them in the desired direction and his contribution to ecclesiology is likely to be very different to the intriguing exercises in abstraction which came from the pen of Benedict XVI (1927–2022; pope 2005-2013, pope emeritus 2013-2022). Whether that means it becomes simultaneously possible for the church simultaneously to continue to condemn homosexuality as a sin yet approve priests giving a blessing to those in a same-sex marriage remains to be seen but in many places, it would merely be an acknowledgement of what’s already happening. Still, those who enjoy the process of such things more than the outcome can be assured there'll be much weeping and gnashing of teeth during the modules and some rending of garments on the way out.

.JPG)