Grand (pronounced grand)

(1) Impressive in size, appearance, or general effect.

(2) Stately, majestic, or dignified.

(3) Highly ambitious or idealistic.

(4) Magnificent or splendid.

(5) Noble or revered.

(6) Highest, or very high, in rank or official dignity.

(7) Main or principal; chief; the most superior.

(8) Of great importance, distinction, or pretension.

(9) Complete or comprehensive (usually as the “grand

total”).

(10) Pretending to grandeur, as a result of minor success,

good fortune, etc; conceited & haughty (often with a modifier such as “rather

grand”, awfully grand” or “insufferably grand”).

(11) First-rate; very good; splendid.

(12) In musical composition, written on a large scale or

for a large ensemble (grand fugue, grand opera etc) and technically meaning

originally “containing all the parts proper to a given form of composition”.

(13) In music, the slang for the concert grand piano

(sometimes as “concert grand”).

(14) In informal use, an amount equal to a thousand pounds

or dollars.

(15) In genealogy, a combining (prefix) form used to

denote “one generation more remote” (grandfather, grand uncle etc).

1350–1400: From the Middle English graund, grond, grand, graunt & grant, from the Anglo-Norman graunt,

from the Old French grant & grand (large, tall; grown-up; great,

powerful, important; strict, severe; extensive; numerous), from the Latin grandis (big, great; full, abundant; full-grown

(and figuratively “strong, powerful, weighty, severe”, of unknown origin. Words conveying a similar sense (depending on

context includes ambitious, awe-inspiring, dignified, glorious, grandiose,

imposing, large, lofty, luxurious, magnificent, marvelous, monumental, noble, princely,

regal, royal, exalted, palatial; brilliant, superb opulent, palatial, splendid,

stately, sumptuous, main, large, big & august. Grand is a noun & adjective, grander &

grandest are adjectives, grandness is a noun and grandly an adverb; the noun

plural is grands.

In Vulgar Latin it supplanted magnus (although the phrase magnum

opus (one’s great work) endured) and continued in the Romanic languages. The connotations of "noble, sublime,

lofty, dignified etc” existed in Latin and later were picked up in English

where it gained also the special sense of “imposing”. The meaning “principal, chief, most important”

(especially in the hierarchy of titles) dates from the 1560s while the idea of “something

of very high or noble quality” " is from the early eighteenth

century. As a general term of admiration

(in the sense of “magnificent or splendid” it’s documented since 1816 but as a

modifier to imply perhaps that but definitely size, it had been in use for

centuries: The Grand Jury was an invention of the late fifteenth century, the

grand tour was understood as “an expedition around the important places in

continental Europe undertaken as part of the education of aristocratic young Englishmen)

as early as the 1660s and the grand piano was name in 1797. In technical use it was adapted for use in medicine

as the grand mal (convulsive epilepsy with loss of consciousness), borrowed by

English medicine from the French grand mal (literally “great sickness”) as a

point of clinical distinction from the petit mal (literally “small sickness”)

(an epileptic event where consciousness was not lost).

The use of the prefix grand- in genealogical compounds is

a special case. The original meaning was

“a generation older than” and the earliest known reference is from the early

thirteenth century in the Anglo-French graund

dame (grandmother) & (later) grandsire (grandfather), etymologists

considering the latter possibly modeled on the avunculus magnus (great uncle).

The English grandmother & grandfather formally entered the language

in the fifteenth century and the extension of the concept from “a generation

older than” to “a generation younger than” was adopted in the Elizabethan era (1558-1603)

thus grandson, granddaughter etc. Grand

as a modifier clearly had appeal because in the US, the “Big Canyon” was in

1869 re-named the Grand Canyon and the meaning "a thousand dollars" dates

from 1915 and was originally US underworld slang. In the modern era grand has been appended

whenever there’s a need economically to convey the idea of a “bigger or more

significant” version of something thus such constructions as grand prix, grand

slam, grand larceny, grand theft auto, grand unification theory, grand master (a favorite both of chess players and the Freemasons) etc.

The Grand Jury

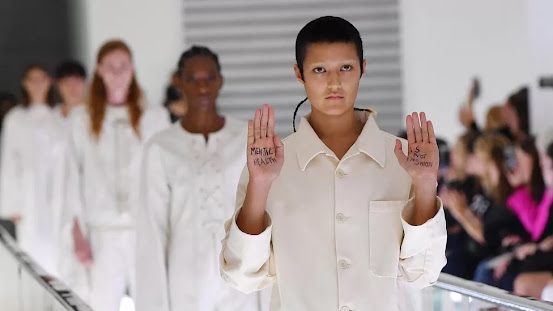

Donald Trump in Manhattan Criminal Court, April 2022.

The Manhattan

grand jury which recently indicted Donald Trump (b 1946; US president

2017-2021) on 34 felony counts of falsification of business records in the

first degree is an example of an institution with origins in twelfth century

England although it didn’t generally become known as the “grand jury” until the

mid-1400s. At least some of the charges

against Mr Trump relate to the accounting associated with “hush-money” payment

made in some way to Stormy Daniels (b 1979; the stage name of Stephanie Gregory

although Mr Trump prefers “horseface” which seems both ungracious and unfair) but

if reports are accurate, he’ll have to face more grand juries to answer more

serious matters.

A grand jury is a group of citizens (usually between

16-23) who review evidence presented by a prosecutor to determine whether the case

made seems sufficiently compelling to bring criminal charges. A grand jury operates in secret and its proceedings

are not open to the public, unlike a trial before a jury (a smaller assembly and

classically a dozen although the numbers now vary and once it was sometimes

called a petit jury). It is this smaller

jury which ultimately will pronounce whether a defendant is guilty or not; all

a grand jury does is determine whether a matter proceeds to trial in which case

it will issue an indictment, which at law is a formal accusation. The origins of the grand jury in medieval

England, where it was used as a means of investigating and accusing individuals

of crimes was to prevent abuses of power by the king and his appointed officers

of state although it was very much designed to protect the gentry and

aristocracy from the king rather than any attempt to extend legal rights to most

of the population.

The grand jury has been retained in the legal systems of only two countries: the US and Liberia. Many jurisdictions now use a single judge or magistrate in a lower court to conduct a preliminary hearing but the principle is the same: what has to be decided is whether, on the basis of the evidence presented, there’s a reasonable prospect a properly instructed (petit) jury would convict. In the US, the grand jury has survived because the institution was enshrined in the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution: “No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger.” The grand jury was thought a vital protection against arbitrary prosecutions by the government, and it was included in the Bill of Rights (1689) to ensure individuals would not be subject to unjustified criminal charges. There is an argument that, by virtue of England’s wondrously flexible unwritten constitution, the grand jury hasn't been abolished but they're merely no longer summoned. It's an interesting theory but few support the notion, the Criminal Justice Act (2003) explicitly transferring the functions to the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) and the model of the office of Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) has been emulated elsewhere in the English-speaking world. Presumably, a resuscitation would require the DPP to convene a grand jury and (if challenged on grounds of validity) the would courts have to concur but as late as 1955 an English court was prepared to hold a court which had not sat for centuries was still extant so the arguments would be interesting.

The “Grand Mercedes”: The Grosser tradition

Der Grossers: 1935 Mercedes-Benz 770 K (W07) of Emperor Shōwa (Hirohita, 1901–1989, emperor of Japan 1926-1989 (left)), Duce & Führer in 1939 Mercedes-Benz 770 K (W150) leading a phalanx of Grossers, Munich, 1940 (centre) and Comrade Marshal Josip Broz Tito (1892–1980) in 1966 Mercedes-Benz 600 Landaulet (W100), Belgrade, 1967 (right).

Produced in three series (770 K (W07 1930–1938 & W150 1939-1945) & 600 (W100 1963-1981)) the usual translation in English of “Grosser Mercedes” is “Grand Mercedes” and that is close to the German understanding which is something between “great”, “big” and “top-of-the-line”. In German & Austrian navies (off & one) between 1901-1945, a Großadmiral was the equivalent to the (five star) Admiral of the Fleet (UK) or Fleet Admiral (US); it was disestablished in 1945. When the 600 (driven to extinction by two oil crises and an array of regulations never envisaged when it was designed) reached the end of the line in 1981, it wasn’t replaced and the factory didn’t return to the idea until a prototype was displayed at the 1997 Tokyo Motor Show. The specification and engineering was intoxicating but the appearance was underwhelming, a feeling reinforced when the production version (2002-2013) emerged not as an imposing Grosser Mercedes but a Maybach, a curious choice which proved the MBAs who came up with the idea should have stuck to washing powder campaigns. The Maybach, which looked something like a big Hyundai, lingered for a decade before an unlamented death.

Grand, Grand Prix & Grand Luxe

1967 Jaguar 420 G (left), 1969 Pontiac Grand Prix J (centre) and 1982 Ford XE Falcon GL 5.8 (351) of the NSW (New South Wales) Highway Patrol (right).

Car

manufacturers were attracted to the word because of the connotations (bigger,

better, more expensive etc). When in

1966 Jaguar updated their slow-selling Mark X, it was integrated into what

proved a short-lived naming convention, based on the engine displacement. Under the system, with a capacity of 4.2

litres (258 cubic inch) the thing had to be called 420 but there was a smaller

saloon in the range so-named so the bigger Mark X was renamed 420 G. Interestingly, when the 420 G was released,

any journalist who asked was told “G” stood for “Grand” which is why that

appeared in the early reports although the factory seems never officially to

have used the word, the text in the brochures reading either 420 G or 420 “G”. The renaming did little to encourage sales although the 420 G lingered on the catalogue until 1970 by which time production had dwindled to a trickle. The tale of the Mark X & 420 G is emblematic of the missed opportunities and mismanagement which would afflict the British industry during the 1970s & 1980s. In 1961, the advanced specification of the Mark X (independent rear suspension, four-wheel disk brakes) made it an outstanding platform and had Jaguar fitted an enlarged version of the Superb V8 they had gained with their purchase of Daimler, it would have been an ideal niche competitor in mid-upper reaches of the lucrative US market. Except for the engine, it needed little change except the development of a good air-conditioning system, then already perfected by Detroit. Although the Daimler V8 and Borg-Warner gearbox couldn't have matched the ultimate refinement of what were by then the finest engine-transmission combinations in the world, the English pair certainly had their charms and would have seduced many.

Pontiac’s memorable 1969 Grand Prix also might have gained ("Grand Prix" most associated with top-level motorsport although it originally was borrowed from Grand Prix de Paris (Big Prize of Paris), a race for thoroughbred horses staged at the Longchamps track) the allure of high performance, something attached to the range upon its introduction as a 1962 model (although by 1967 it had morphed into something grand more in size than dynamic qualities). The 1969-1970 cars remain the most highly regarded, the relative handful of SJ models built with the 428 cubic inch (7.0 litre) HO (High Output) V8 a collectable, those equipped with the four-speed manual gearbox the most sought-after. It was downhill from the early 1970s and by the next decade, there was little about the by then dreary Grand Prix which seemed at all grand.

During the interwar years (1919-1939) “deluxe” was a popular borrowing borrowed from the fashion word, found to be a good label to apply to a car with bling added; a concept which proved so profitable it remains practiced to this day. Deluxe (sometimes as De luxe) was a commercial adaptation of the French de luxe (of luxury), from the Latin luxus (excess), from the primitive Indo-European lewg- (bend, twist) and it begat “Grand Luxe” which was wholly an industry invention. Deluxe and Grand Luxe eventually fell from favour as model names for blinged-up creations became more inventive but the initializations L, DL & GL were adopted by some, the latter surviving longest by which time it was understood to signify just something better equipped and thus more expensive; it’s doubtful many may a literal connection to “Grand Luxe”.

In the matter of Grand Theft Auto (GTA5): Lindsay Lohan v Take-Two Interactive Software Inc et al, New York Court of Appeals (No 24, pp1-11, 29 March 2018)

In a case which took an unremarkable four years from filing to reach New York’s highest appellate court, Lindsay Lohan’s suit against the makers (Take-Two, aka Rockstar) of video game Grand Theft Auto V was dismissed. In a unanimous ruling in March 2018, six judges of the New York Court of Appeals rejected her invasion of privacy claim which alleged one of the game’s characters was based on her. The judges found the "actress/singer" in the game merely resembled a “generic young woman” rather than anyone specific. Unfortunately the judges seemed unacquainted with the concept of the “basic white girl” which might have made the judgment more of a fun read.

Concurring with the 2016 ruling of the New York County Supreme Court which, on appeal, also found for the game’s makers, the judges, as a point of law, accepted the claim a computer game’s character "could be construed a portrait", which "could constitute an invasion of an individual’s privacy" but, on the facts of the case, the likeness was "not sufficiently strong". The “… artistic renderings are an indistinct, satirical representation of the style, look and persona of a modern, beach-going young woman... that is not recognizable as the plaintiff" Judge Eugene Fahey (b 1951) wrote in his ruling. Judge Fahey's words recalled those of Potter Stewart (1915–1985; associate justice of the US Supreme Court 1958-1981) when in Jacobellis v Ohio (378 U.S. 184 (1964) he wrote: “I shall not today attempt further to define… and perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it…” Judge Fahey knew a basic white girl when he saw one; he just couldn't name her. Lindsay Lohan's lawyers did not seek leave to appeal.

The game’s

developers may have taken the risk of incurring Lindsay Lohan’s wrath and

indignation because they’d been lured into a false sense of security by Crooked

Hillary Clinton (b 1947; US secretary of state 2009-2013) not filing a writ

after a likeness of her appeared on GTA 4’s (2008) Statue Of Happiness which

stands on Happiness Island, just off the coast of Liberty City. The Statue of Happiness was a blatant knock-off

of the New York’s Statue of Liberty and crooked Hillary became a determined and

acerbic critic of Rockstar and the GTA franchise after the “Hot Coffee” scandal. That controversy arose after modders promulgated

a code which in GTA: San Andreas’ release

(2004) unlocked a hidden “mini-game” which allowed players to control explicit

on-screen sex acts. Men having sex with

women to whom they don’t enjoy benefit of marriage is a bit of a sore point

with crooked Hillary, then a US senator (Democrat-NY), who embarked on a campaign

for new regulations be imposed on the industry and the most immediate

consequence was the SSRB (Entertainment Software Rating Board) launching an investigation,

subsequently raising GTA: San Andreas’ rating from “M” (Mature) to “AO” (Adults

Only 18) until the objectionable content was removed. For those who wondered if the frightening

visage on the GTA 4 statute really was what some suspected, the object’s file

name was “stat_hilberty01.wdr”.

Roskstar's Statue Of Happiness in GTA 4 (2008, left) and an official photograph of crooked Hillary Clinton (right).

Rockstar seeking

vengeance was understandable because crooked Hillary’s moral crusade proved

tiresome for the company. Once the ESRB

had been nudged into action, crooked Hillary petitioned the FTC (Federal Trade

Commission) to (1) find the source of the game's “graphic pornographic and violent content”,

(2) determine if it should be slapped with an AO rating and (3) “examine the

adequacy of the retailers' rating enforcement policies.” Not content, she then announced she’d be sponsoring

in the senate a bill for an act which would make it a federal crime (with a

mandatory US$5,000 fine) to sell to anyone under 18, violent or sexually

explicit video games; the Family Entertainment Protection Act was filed on 17

December 2005 and referred to the Committee on Commerce, Science and

Transportation, where quietly it was allowed to expire.

While the act slowly was being strangled in committee hearings, the FTC and Rockstar reached a settlement, the commission ruling the company had violated the Federal Trade Commission Act (1914) by failing to disclose the inclusion of “unused, but potentially viewable” explicit content” (that it was enabled by a third party was held to be “not relevant”). The settlement required Rockstar “clearly and prominently disclose on product packaging and in any promotion or advertisement for electronic games, content relevant to the rating, unless that content had been disclosed sufficiently in prior submissions to the rating authority” with violations punishable by a fine of up to US$11,000. In the spirit of the now again fashionable Calvin Coolidge (1872-1933; US president 1923-1929) era capitalism, no fine was imposed for the “Hot Coffee incident”, presumably because the company had already booked a US$24.5 million loss from the product recall earlier mandated.