Vorticism (pronounced vawr-tuh-siz-uhm)

A short-lived movement in the British avant-garde, nurtured

by Wyndham Lewis, which climaxed in a London exhibition in 1915 before

being absorbed.

1914: The construct was vortic + -ism. The Latin vortic was the stem of vortex, (genitive vorticis), an archaic from of vertex (an eddy of water, wind, or flame; whirlpool; whirlwind whirl, top, crown, peak, summit), from vertō (to turn around, turn about) from vertere (to turn), from the primitive Indo-European wer (to turn; bend). The –ism suffix is from the Ancient Greek ισμός (ismós) & -isma noun suffixes, often directly, sometimes through the Latin –ismus & isma (from where English picked up ize) and sometimes through the French –isme or the German –ismus, all ultimately from the Ancient Greek (where it tended more specifically to express a finished act or thing done). It appeared in loanwords from Greek, where it was used to form abstract nouns of action, state, condition or doctrine from verbs and on this model, was used as a productive suffix in the formation of nouns denoting action or practice, state or condition, principles, doctrines, a usage or characteristic, devotion or adherence (criticism; barbarism; Darwinism; despotism; plagiarism; realism; witticism etc). Vorticism is a noun, vorticist is a noun & adjective and vorticistic is an adjective; the noun plural was vorticists, The forms vorticistically & vortical seem never to have come into use.

The name Vorticism

was said to have been coined in 1914 by the poet Ezra Pound (1885–1972) years

before fascism and madness possessed his soul.

Pound had already used the word "vortex" to describe the effect modernist

poetry was having on intellectual thought in Europe and he used the word not in

the somewhat vague sense it often assumed when used figuratively to suggest swirling

turbulence but rather as a mathematician or meteorologist might: an energy

which gathers from the surrounding chaos what’s around, imparts to it a geometrical

form which, intensifying as it goes, arrives at a single point. Pound’s coining of the name is generally

accepted but some historians claim the name was chosen by the Italian futurist

Umberto Boccioni (1882-1916) who claimed all creative art could emanate only from

a vortex of emotions.

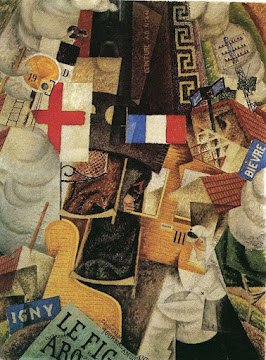

Vorticism flourished only briefly between 1912-1915 as an overly aggressive reaction to what was held to be an excessive attachment to and

veneration for delicacy and beauty in art and literature, preferring to

celebrate the tools of modernity, the violence and energy of machines. In painting and sculpture the angles were

sharp and the lines bold, colors displayed in juxtaposition to emphasize the starkness of their difference and there was a reverence for

geometric form and repetition. The

movement in 1914 published its own magazine:

Blast: the Review of the Great English

Vortex which was more manifesto than critique, a London-based attempt to gather together the artists and writers of the avant‐garde

in one coherent movement. It wanted the shock of the new.

The idea was an art

which reflected the strains of the vortices of a modern life in what was increasingly a machine age. Thus, although

it remains a footnote in the history of modern art, the label Vorticism refers to

a political and sociological point rather than a distinct style such as contemporaries like Cubism or Futurism. The timing was of course

unfortunate and the outbreak of World War I (1914-1918) robbed Vorticism of much of its

initial energy; the exhibition eventually staged in London’s Doré

Gallery in 1915 remained a one-off and, like much of the pre-1914 world,

Vorticism didn’t survive the World War.

Being unappreciated at the time, most of the paintings of the vorticists were lost but retrospectives have been assembled from what remains and the still extant photographic record and there’s now a better understanding of the legacy and the influence on art deco, dada, surrealism, pop art, indeed, just about any abstract form. Graphic art too benefited from the techniques, the sense of line and color identifiable in agitprop, twentieth century advertising and, most practically, the “dazzle” camouflage used by admiralties in both world wars as a form of disguise for ships.

Juan Garrido, a graphic designer based in Caracas, Venezuela, created the display typeface Vorticism in 2013. Reflecting the cultural and linguistic influences, while there are a number of typefaces called futurism (or some variation) and some based on the word "vortex", Mr Garrido's "Vorticism" is uniquely named.

Lindsay Lohan in the Vorticism typeface.

Even in 1912, Vorticism’s use of bold, abstract, and geometric forms (often depicting movement and mechanical apparatuses) wasn’t new but the movement had an energy which attracted those wanting to create imagery which marked a dramatic break from the representational forms which then were still dominant early in the ear which would come to be known as the dawn of modernity. In that sense, Vorticism is understood as one of a number of movements embracing a new aesthetic reflecting the dynamism and energy of the modern world. That as a distinct entity Vorticism didn’t endure was in a way an indication of success rather than failure because its motifs and techniques were co-opted to serve as foundational aspects of many movements in modern art, the abstract and geometric forms underpinning Futurism and Constructivism as well as becoming a staple of commercial graphic art and advertising. Perhaps the most obvious influence was the artistic legitimization of the integration of text into images, a practice borrowed from commerce and a notable signature of Dada and Surrealism. The use of text as a visual element challenged traditional boundaries between different art forms, a tension which enabled Pop art to create was in some ways a novel ecosystem. However, those same motifs have been used also as something illustrative of the destructive tendencies of the speed and spread of mechanical and industrial reality which the vorticists championed and Precisionism & Bauhaus celebrated, at least in a sanitized and idealized way which hid the essential ugliness below.