Beetle (pronounced beet-l)

(1) Any of numerous insects of the order Coleoptera, having

biting mouthparts and characterized by hard, horny forewings modified to form

shell-like protective elytra forewings that cover and protect the membranous

flight wings.

(2) Used loosely, any of various insects resembling true beetles.

(3) A game of chance in which players attempt to complete

a drawing of a beetle, different dice rolls allowing them to add the various

body parts.

(4) A heavy hammering or ramming instrument, usually of

wood, used to drive wedges, force down paving stones, compress loose earth etc.

(5) A machine in which fabrics are subjected to a

hammering process while passing over rollers, as in cotton mills; used to

finish cloth and other fabrics, they’re known also as a “beetling machine”

(6) To use a beetle on; to drive, ram, beat or crush with

a beetle; to finish cloth or other fabrics with a beetling machine.

(7) In slang, quickly to move; to scurry (mostly UK),

used also in the form “beetle off”.

(8) Something projecting, jutting out or overhanging

(used to describe geological formation and, in human physiology, often in the

form beetle browed).

(9) By extension, literally or figuratively, to hang or

tower over someone in a threatening or menacing manner.

(10) In slang, the original Volkswagen and the later

retro-model, based on the resemblance (in silhouette) of the car to the insect;

used with and without an initial capital; the alternative slang “bug” was also analogous

with descriptions of the insects.

Pre 900: From the late Middle English bittil, bitil, betylle & bityl, from the Old English bitula, bitela, bītel & bīetel (beetle (and apparently

originally meaning “little biter; biting insect”)), from bēatan (to beat) (and related to bitela, bitel & betl,

from bītan (to bite) & bitol (teeth)), from the Proto-West

Germanic bitilō & bītil, from the Proto-Germanic bitilô & bītilaz (that which tends to bite, biter, beetle), the construct

being bite + -le. Bite was from the Middle English biten, from the Old English bītan (bite), from the Proto-West

Germanic bītan, from the

Proto-Germanic bītaną (bite), from

the primitive Indo-European bheyd-

(split) and the -le suffix was from the Middle English -elen, -len & -lien, from the Old English -lian

(the frequentative verbal suffix), from the Proto-Germanic -lōną (the frequentative verbal suffix)

and was cognate with the West Frisian -elje,

the Dutch -elen, the German -eln, the Danish -le, the Swedish -la and

the Icelandic -la. It was used as a frequentative suffix of

verbs, indicating repetition or continuousness.

The forms in Old English were cognate with the Old High German bicco

(beetle), the Danish bille (beetle), the

Icelandic bitil & bitul (a bite, bit) and the Faroese bitil (small piece, bittock).

In architecture, what was historically was the "beetle brow" window is now usually called "the eyebrow". A classic example of a beetle-brow was that of Rudolf Hess (1894–1987; Nazi deputy führer 1933-1941).

Beetle in the sense of the tool used to work wood, stonework, fabric etc also dates from before 900 and was from the Middle English betel & bitille (mallet, hammer), from the Old English bītel, bētel & bȳtel which was cognate with the Middle Low German bētel (chisel), from bēatan & bētan (beat) and related to the Old Norse beytill (penis). The adjectival sense applied originally to human physiology (as beetle-browed) and later extended to geological formations (as a back-formation of beetle-browed) and architecture where it survives as the “eyebrow” window constructions mounted in sloping roofs. The mid-fourteenth century Middle English bitelbrouwed (grim-browed, sullen (literally “beetle-browed”)) is thought to have been an allusion to the many beetles with bushy antennae, the construct being the early thirteenth century bitel (in the sense of "sharp-edged, sharp" which was probably a compound from the Old English bitol (biting, sharp) + brow, which in Middle English meant "eyebrow" rather than "forehead." Although the history of use in distant oral traditions is of course murky, it may be from there that the Shakespearean back-formation (from Hamlet (1602)) in the sense of "project, overhang" was coined, perhaps from bitelbrouwed. As applied to geological formations, the meaning “dangerously to overhang cliffs etc” dates from circa 1600. The alternative spellings bittle, betel & bittil are all long obsolete. Beetle is a noun & verb & adjective, beetled is a verb, beetling is a verb & adjective and beetler is a noun; the noun plural is beetles.

Gazing back.

Even before he went mad (something of a calling among German philosophers) Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) would warn the impressionable: “And if you gaze for long into an abyss, the abyss gazes also into you.” In some European towns, gaze for long at the houses and Rudolf Hess also gazes at you. Attending the first Nuremberg Trial (1945-1946) as a journalist, the author Rebecca West (1892–1983) perceived an abyss in Hess, writing he was “…so plainly mad… He looked as if his mind had no surface, as if every part of it had been blasted away except the depth where the nightmares lived.” Imprisoned for life (Count 1: Conspiracy & Count 2: Crimes against peace) by the IMT (International Military Tribunal), Hess would spend some 46 years in captivity and when in 1987 he took his own life, he was the last survivor of the 21 who has stood in the dock to receive their sentences. Opinion remains divided over whether Hess was “mad” in either the clinical or legal sense but his conduct during the trial and what is known of his decades in Berlin’s Spandau prison (the last 20-odd years as the vast facility’s sole inmate) does suggest he was at least highly eccentric.

The Beetle (Volkswagen Type 1)

First built before World War II (1939-1945), the Volkswagen (the construct being volks (people) + wagen (car)) car didn’t pick up the nickname “beetle” until 1946, the allied occupation forces translating it from the German Käfer and it caught on, lasting until the last one left a factory in Mexico in 2003 although in different places it gained other monikers, the Americans during the 1950s liking “bug” and the French coccinelle (ladybug) and as sales gathered strength around the planet, there were literally dozens of local variations, the more visually memorable including: including: bintus (Tortoise) in Nigeria, pulga (flea) in Colombia, ඉබ්බා (tortoise) in Sri Lanka, sapito (little toad) in Perú, peta (turtle) in Bolivia, folcika (bug) in Bosnia and Herzegovina, kostenurka (turtle) in Bulgaria, baratinha (little cockroach) in Cape Verde, poncho in Chile and Venezuela. buba (bug) in Croatia, boblen (the bubble), asfaltboblen (the asphalt bubble), gravid rulleskøjte (pregnant rollerskate) & Hitlerslæden (Hitler-sled) in Denmark. cepillo (brush) in the Dominican Republic, fakrouna (tortoise) in Libya, kupla (bubble) & Aatun kosto (Adi's revenge) in Finland, cucaracha (cockroach) in Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras, Kodok (frog) in Indonesia, ghoorbaghei (قورباغه ای) (frog) in Iran, agroga عكروكة (little frog) & rag-gah ركـّة (little turtle) in Iraq, maggiolino (maybug) in Italy, kodok (frog) in Malaysia, pulguita (little flea) in Mexico and much of Latin America, boble (bubble) in Norway, kotseng kuba (hunchback car) & boks (tin can) in the Philippines, garbus (hunchback) in Poland, mwendo wa kobe (tortoise speed) in Swahili and banju maqlub (literally “upside down bathtub”) in Malta.

A ground beetle (left), a first generation der Käfer (the Beetle, 1939-2003) (centre) and an "New Beetle" (1997-2011). Despite the appearance, the "New Beetle" was of front engine & front-wheel-drive configuration, essentially a re-bodied Volkswagen Golf. The new car was sold purely as a retro, the price paid for the style, certain packaging inefficiencies.

The Beetle (technically, originally the KdF-Wagen and later the Volkswagen Type 1) was one of the products nominally associated with the Nazi regime’s Gemeinschaft Kraft durch Freude (KdF, “Strength Through Joy”), the state-controlled organization which was under the auspices of the Deutsche Arbeitsfront (German Labor Front) which replaced the independent labor unions. Operating medical services, cruise liners and holiday resorts for the working class, the KdF envisaged the Volkswagen as a European Model T Ford in that it would be available in sufficient numbers and at a price affordable by the working man, something made easier still by the Sparkarte (savings booklet) plan under which a deposit would be paid with the balance to be met in instalments. Once fully paid, a Volkswagen would be delivered. All this was announced in 1939 but the war meant that not one Volkswagen was ever delivered to any of those who diligently continued to make their payments as late as 1943. Whether, even without a war, the scheme could have continued with the price set at a politically sensitive 990 Reichsmarks is uncertain. That was certainly below the cost of production and although the Ford Model T had demonstrated how radically production costs could be lowered once the efficiencies of mass-production reached critical mass, there were features unique to the US economy which may never have manifested in the Nazi system, even under sustained peace although, had the Nazis won the war, from the Atlantic to the Urals they'd have had a vast pool of slave labor, a obvious way to reduce unit labor costs. As it was, it wasn’t until 1964 that some of the participants in the Sparkarte were granted a settlement under which they received a discount (between 9-14%) which could be credited against a new Beetle. Inflation and the conversion in 1948 from Reichsmark to Deutschmark make it difficult accurately to assess the justice of that but the consensus was Volkswagen got a good deal. The settlement was also limited, nobody resident in the GDR (The German Democratic Republic, the old East Germany (1949-1990)) or elsewhere behind the iron curtain received even a Reichspfennig (cent).

Small, life-size & larger than life: A scale model (left), a 1955 Volkswagen Beetle (centre) and the “Huge Bug”, on the road with the 1959 Cabriolet used as a template.

Produced or assembled around the world between 1938-2003, over 21.5 million Beetles were made and there were also untold millions of scale models, ranging from small, colorful molded plastic toys distributed in cereal boxes (an early form of “indirect marketing” to children) through the ubiquitous “Matchbox Toys” to some highly detailed and expensive renditions, some powered by electric motors. However, as far as in known, there's been only one “up-scaled” Beetle and so impressive was it in execution, until seen with objects (ideally a standard Beetle) to give some sense of the size, it’s not immediately obvious the thing is some 40% bigger. While it may be tempting to call this a “Super Beetle” that would only confuse because the factory applied that label to a version introduced in 1970 and customers nick-named those “Super Bug” so that’s taken too; maybe “Big Bug” is best although the builders liked “Huge Bug”.

The Huge Bug was created by a Californian father and son team who disassembled a 1959 Beetle Cabriolet so the relevant components could be scanned and digitized, enabling versions 40% larger to be fabricated. Built on the chassis of a Dodge Magnum, mechanical components were carried over so the Huge Bug features a specification which would have astonished Germans (or anyone else) in 1957, including a 345 cubic inch (5.7 litre) Hemi V8, automatic transmission, power steering, heated seats, air conditioning & power windows. Not unexpectedly, whenever parked, the Huge Bug attracts those wanting a unique backdrop for selfies. If the Huge Bug seems too conventional (if large) an approach, others have allowed their imagination to wander in other directions.

Herbie, the love bug

Lindsay Lohan (left) among the Beetles (centre) on the red carpet for the Los Angeles premiere of Herbie Fully Loaded (2005), El Capitan Theater, Hollywood, Los Angeles, 19 June 19, 2005. The Beetle (right) was one of the many replica “Herbies” in attendance and, on the day, Ms Lohan (using the celebrity-endorsed black Sharpie) autographed the glove-box lid, removed for the purpose.

In a Beetle it’s a simple task quickly to remove and re-fit a lid but unfortunately it was upside down when signed. Autographs on glove-box lids (and other parts) are a thing and the most famous (and numerous) are those of Carroll Shelby (1923–2012) on Shelby American AC Cobras and Mustangs. Many are authentic because for a donation to the Shelby foundation (typically around US$250) an owner could send to Shelby American headquarters in California a lid with a SSAE (stamped, self-addressed envelope) and it would come back duly signed and with a letter of authenticity (though one owner noted dryly the felt pen (silver ink) he’d enclosed wasn’t returned. There are many slight variations in the signatures which hints they were done by hand and not an auto-pen although those that differ most are the ones signed while the lid was fixed to the car; for most it’s an unnatural action to sign on other than a flat, horizontal surface. There are also some of questionable provenance, not all of which are on Cobra replicas built long after Carroll Shelby’s death and “Carroll Shelby glove-box signature vinyl transfer tapes” are available on-line in black, white and silver for as little as US$6.00. Beware of imitations one might say but given there are over 50,000 “imitation” Cobras against a thousand-odd originals, the fake signature industry is sort of in the same spirit.

One of the cars used in the track racing sequences, now on display in the Peterson Automotive Museum on Wilshire Boulevard, Los Angeles, California (left), a Disney Pictures promotional image (centre) and a Herbie “replica” (with glove-box lid signed by Lindsay Lohan) built on a modified 1964 Beetle (right).

Before the release in 2005 of Herbie: Fully Loaded, following the first "Herbie" film (The Love Bug (1968)), there had been three sequels and a television series so the ecosystem of Herbie replicas (clones, tributes etc) was well-populated and as a promotional gimmick Disney Pictures invited fans to bring their replicas to line the red carpet at the Los Angeles premiere. Producing a “true” Herbie replica is technically possible but not all will be the same because even within each film there were variations in the appearance because a number of Beetles were required for the filming with not all identical in every visual aspect. In post-production, there is a “continuity editor” who is tasked with removing or disguising such inconsistencies but minor details, especially if not in any way significant, often slip through something which delights the film obsessives who curate sites documenting the “errors”. Among Beetle (especially the pre 1968 models) collectors there’s a faction of originality police (as uncompromising as any found in the communities patrolling vintage Ferraris, Corvettes, Jaguars, Porsches and such) and when the Herbie “replica” (above right) was offered for sale (as a “Herbie-Style 1964 Volkswagen Beetle Sunroof Sedan”) they were there to pounce, noting:

(1) The last

year for the Golde folding sunroof was 1963, 1964 Sunroof Sedans fitted with a steel,

sliding-roof. The consensus was either the

roof from an earlier Sunroof Sedan was spliced on or a hole was cut for

salvaged Golde assembly to be installed.

Neither would be technically difficult for someone with the parts and

skill but an inspection would be required to know which and on the basis of the

photographs the work had been done well.

(2) The hood (“bonnet” over the frunk) was from an earlier model (with a pre-1963 Wolfsburg crest).

(3) The licence plate light was from 1963 (the updated engine and conversion to 12-volt electrics (both common in early Beetles) were disclosed in the sales blurb).

(4) The radio antenna was on the driver’s side whereas in the film it appears on the passenger’s side and there were many detail differences (decals and such) but there were inconsistencies also in the film.

Herr Professor Porsche

Herr Professor Ferdinand Porsche (1875–1951) didn't exactly "invent" the concept of the Beetle but he was much involved in the design although Adolf Hitler (1889-1945; Führer (leader) and German head of government 1933-1945 & head of state 1934-1945) claimed to be the one who insisted on the use of an air-cooled engine because "not every rural doctor has a garage". Porsche's appointment as a professor was a personal gift from the Führer who created them (he made his personal photographer a professor!) about as freely as he would later churn out Field Marshals. There were many Volkswagens produced during the war but all were delivered either to the military or the Nazi Party organization where they were part of the widespread corruption endemic to the Third Reich, the extent of which wasn’t understood until well after the demise of the regime. The wartime models were starkly utilitarian and this continued between 1945-1947 when production resumed to supply the needs of the Allied occupying forces, the bulk of the output being taken up by the British Army, the Wolfsburg factory being in the British zone. As was the practice immediately after the war, the plan had been to ship the tooling to the UK and begin production there but the UK manufacturers, after inspecting the vehicle, pronounced it wholly unsuitable for civilian purposes and too primitive to appeal to customers. Accordingly, the factory remained in Germany and civilian deliveries began in 1947, initially only in the home market but within a few years, export sales were growing and by the mid-1950s, the Beetle was a success even in the US market, something which must have seem improbable in 1949 when two were sold. The platform proved adaptable too, the original two-door saloon and cabriolet augmented by a van on a modified chassis which was eventually built in a bewildering array of body styles (and made famous as the Kombi and Microbus (Type 2) models which became cult machines of the 1960s counter-culture) and the stylish, low-slung Karmann-Ghia (the classic Type 14 and the later Type 34 & Type 145 (Brazil), sold as a 2+2 coupé and convertible. Later there would be attempts to use more modern body styling while preserving the mechanical layout (the Type 3, 1961-1973 and Type 4 (411/412), 1968-1974) but the approach was by the early 1970s understood to be a dead end although the concept was until 1982 pursued by Volkswagen's Brazilian operation.

Herr Professor Ferdinand Porsche (1875–1951) explaining the KdF-Wagen (Strength Through Joy car which, in the post-war years would become the Volkswagen ("people's car" which, as the range proliferated would come to be called the "Type 1" (Beetle) to Adolf Hitler (1889-1945; Führer (leader) and German head of government 1933-1945 & head of state 1934-1945) during the ceremony marking the laying of the foundation stone at the site of the Volkswagen factory, in Germany's Lower Saxony region, 26 May 1938 (which Christians mark as the Solemnity of the Ascension of Jesus Christ, commemorating the bodily Ascension of Christ to Heaven) (left). The visit would have been a pleasant diversion for Hitler who was at the time immersed in planning for the Nazi's takeover of Czechoslovakia and later the same day, during a secret meeting, the professor would display a scale-model of an upcoming high-performance version (right).

The name of the location where the factory sat became well-known in the 1950s when Beetles spread around the world but the name Wolfsburg wasn't gazetted until May 1945 while the area was under occupation by the US Army, the name a reference to the nearly eponymous castle, the first known mention of which dates from 1302 in a document mentioning the structure as the seat of the noble lineage of Bartensleben. The city had been founded by the Nazis on 1 July 1938 as the Stadt des KdF-Wagens bei Fallersleben (City of the Strength Through Joy car at Fallersleben), an example of a "company town" which, centred around the village of Fallersleben, included not only the industrial plant by also housing for workers and the associated service and recreational facilities. As things were then done, the SS (ᛋᛋ in Armanen runes; Schutzstaffel 1923-1945 (literally “protection squadron” but translated variously as “protection squad”, “security section" etc) in 1942 established the nearby Arbeitsdorf concentration camp as a source of cheap (and expendable) labour but the experiment proved industrially inefficient and it was shut down after a few months.

The Beetle also begat what are regarded as the classic Porsches (the 356 (1948-1965), the 911 (1964-1998) and 912 (1965-1969 & 1976)). Although documents filed in court over the years would prove Ferdinand Porsche’s (1875-1951) involvement in the design of the Beetle revealed not quite the originality of thought that long was the stuff of legend (as a subsequent financial settlement acknowledged), he was attached to the concept and for reasons of economic necessity alone, the salient features of the Beetle (the separate platform, the air-cooled flat engine, rear wheel drive and the basic shape) were transferred to the early post-war Porsches and while for many reasons features like liquid cooling later had to be adopted, the basic concept of the 1938 KdF-Wagen is still identifiable in today’s 911s. The Beetle had many virtues as might be surmised given it was in more-or-less continuous production for sixty-five years during which over 20 million were made. However, one common complaint was the lack of power, something which became more apparent as the years went by and average highway speeds rose. The factory gradually increased both displacement & power and an after-market industry arose to supply those who wanted more, the results ranging from mild to wild. One of the most dramatic approaches was that taken in 1969 by Emerson Fittipaldi (b 1946) who would later twice win both the Formula One World Championship and the Indianapolis 500.

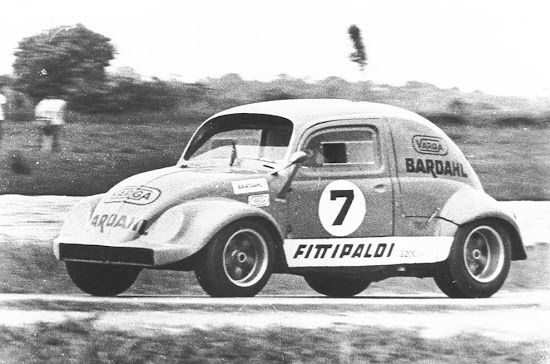

The Fittipaldi 3200

Team Fittipaldi in late 1969 entered the Rio 1000 km race at

the Jacarepagua circuit, intending to run a prototype with an Alfa Romeo engine but after

suffering delays in the fabrication of some parts, it was clear there would be insufficient

time to prepare the car. No other

competitive machine was immediately available so the decision was taken to

improvise and build a twin-engined Volkswagen Beetle, both car and engines in

ample supply, local production having begun in 1953. On paper, the leading opposition (Alfa Romeo

T33s, a Ford GT40 and a Lola T70 was formidable but the Beetle, with two tuned

1600 cm3 (98 cubic inch) engines, would generate some 400 horsepower

in a car weighing a mere 407kg (897 lb) car.

Expectations weren't high and other teams were dismissive of the threat yet

in qualifying, the Beetle set the second fastest time and in the

race proved competitive, running for some time second to the leading Alfa Romeo

T33 until a broken gearbox forced retirement.

Fittipaldi 3200, Interlagos, 1969. The car competed on Pirelli CN87 Cinturatos (which were for street rather than race-track use) tyres which was an interesting choice but gearbox failures meant it never raced long enough for their durability to be determined.

The idea of twin-engined cars was nothing new, Enzo Ferrari (1898-1988) in 1935 having entered the Alfa Romeo Bimotor in the Grand Prix held on the faster circuits. At the time a quick solution to counter the revolutionary new Mercedes-Benz and Auto-Union race cars, the Bimotor had one supercharged straight-eight mounted at each end, both providing power to the rear wheels. It was certainly fast, timed at 335 km/h (208 mph) in trials and on the circuits it could match anything in straight-line speed but its Achilles heel was that which has beset most twin-engined racing cars, high fuel consumption & tyre wear and a tendency to break drive-train components. There were some successful adoptions when less powerful engines were used and the goal was traction rather than outright speed (such as the Citroën 2CV Sahara (694 of which were built between 1958-1971)) but usually there were easier ways to achieve the same thing. Accordingly, while the multi-engine idea proved effective (indeed sometimes essential) when nothing but straight line speed was demanded (such as land-speed record (LSR) attempts or drag-racing), in events when corners needed to be negotiated, it proved a cul-de-sac. There was certainly potential as the handful of "Twinis" (twin-engined versions of the BMC (British Motor Corporation) Mini (1959-2000) built in the 1960s demonstrated. The original Twini had been built by constructor John Cooper (1923–2000 and associated with the Mini Cooper) after he'd observed a twin-engined Mini-Moke (a utilitarian vehicle based on the Mini's platform) being tested for the military. Cooper's Twini worked and was rapid but after being wrecked in an accident (not directly related to the novel configuration), the project was abandoned.

Still, in 1969, Team Fittipaldi had nothing faster

available and while on paper, the bastard Beetle seemed unsuited to the task as

the Jacarepagua circuit then was much twistier than it would become, it would

certainly have a more than competitive power to weight ratio, the low mass likely to

make tyre wear less of a problem. According

to Brazilian legend, in the spirit of the Q&D (quick & dirty) spirit of

the machines hurried assembly, after some quick calculations on a slide-rule,

the design process moved rapidly from the backs of envelopes to paper napkins

at the Churrascaria Interlagos Brazilian Barbecue House where steaks and red wine were ordered. Returning to the workshop, most of the chassis was fabricated against

chalk-marks on garage floor while the intricate linkages required to ensure the

fuel-flow to the four Weber DC045 carburetors were constructed using cigarette

packets as templates to maintain the correct distance between components. In the race, the linkages performed

faultlessly.

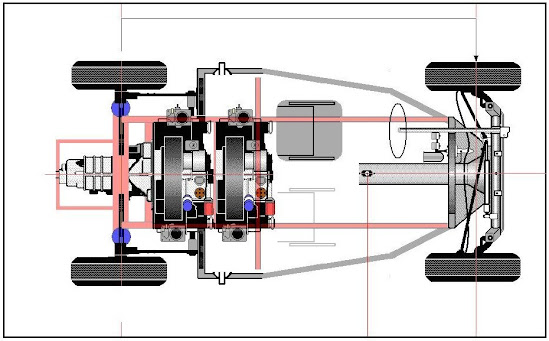

Fittipaldi 3200: The re-configuration of the chassis essentially transformed the rear-engined Beetle into a mid-engined car, the engines between the driver and the rear-axle line, behind which sat the transaxle.

The chassis used a standard VW platform, cut just behind the driver’s seat where a tubular sub-frame was attached. The front suspension and steering was retained although larger Porsche drum brakes were used in deference to the higher speeds which would be attained. Remarkably, Beetle type swing axles were used at the rear which sounds frightening but these had the advantage of providing much negative camber and on the smooth and predictable surface of a race-track, especially in the hands of a race-driver, their behavior would not be as disconcerting as their reputation might suggest. Two standard 1600cm3 Beetle engines (thus the 3200 designation) were fitted for the shake down tests and once the proof-of-concept had been verified, they were sent for tuning, high-performance Porsche parts used and the displacement of each increased to 2200cm3 (134 cubic inch). The engines proved powerful but too much for the bottom end, actually breaking a crankshaft (a reasonable achievement) so the stroke was shortened, yielding a final displacement only slightly greater than the original specification while maintaining the ability to sustain higher engine speeds.

Fittipaldi 3200 (1969) schematic (left) and Porsche 908/01 LH Coupé (1968–1969) (right): The 3200's concept of a mid-engined, air-cooled, flat-eight coupe was essentially the same as the Porsche 908 but the Fittipaldi 3200's added features included drum brakes, swing axles and a driver's seat which doubled as the fuel tank. There might have been some drivers of the early (and lethal) Porsche 917s who would have declined an offer to race the 3200, thinking it "too dangerous".

The rear engine was attached in a conventional arrangement through a Porsche five-speed transaxle although first gear was blanked-off (shades of the British trick of the 1950s which discarded the "stump-puller" first gear to create a "close ratio" three-speed box) because of a noted proclivity for stripping the cogs while the front engine was connected to the rear by a rubber joint with the crank phased at 90o to the rear so the power sequenced correctly. Twin oil coolers were mounted in the front bumper while the air-cooling was also enhanced, the windscreen angled more acutely to create at the top an aperture through which air could be ducted via flexible channels in the roof. Most interesting however was the fuel tank. To satisfy the thirst of the two engines, the 3200 carried 100 litres (26.4 (US) / 22 (Imperial) gallons) of a volatile ethanol-based cocktail in an aluminum tank which was custom built to fit car: It formed the driver’s seat!

Incongruity: The Beetle and the prototypes, Interlagos, 1969

In the Rio de Janeiro 1000 kilometre race on the Guanabara

circuit, the 3200, qualified 2nd and ran strongly in the race, running

as high as second, the sight of a Beetle holding off illustrious machinery

such as a Porsche special, a Lola-Chevrolet R70, and a Ford GT40, one of

motorsport’s less expected sights.

Unfortunately, in the twin-engined tradition (there have been some glorious failures and a handful of specialized successes), it proved fast but

fragile, retiring with gearbox failure before half an hour had elapsed. It raced once more but proved no more

reliable.

How to have fun with a Beetle.

Caffeine

addiction is one of humanity’s most widespread vices and it extends to those

driving cars. In famous tort case, Stella Liebeck v. McDonald's Restaurants,

P.T.S., Inc. and McDonald's International, Inc (1994 Extra LEXIS 23

(Bernalillo County, N.M. Dist. Ct. 1994), 1995 WL 360309 (Bernalillo County,

N.M. Dist. Ct. 1994), a passenger in a car (a 1989 model with no cup holders)

received severe burns from spilled coffee, just purchased from a McDonald’s

drive-through. Although the matter

received much publicity on the basis it was absurd to be able to sue for being

burned by spilling what was known by all to be “hot” and the case came to be cited

as an example of “frivolous” litigation, there were technical reasons why some

liability should have been ascribed to McDonalds. The jury awarded some US$2.6 million in

damages although this was, on appeal, reduced to US$640,000 and the matter was

settled out of court before a further appeal.

How to have coffee in a Beetle

In the twenty-first century,

some now judge cars on the basis of the count, capacity & convenience of its

cup-holders but in the less regulated environment of the FRG (Federal Republic

of Germany, the old West Germany, 1949-1990) of 1959, one company anticipated

the future trend by offering a dashboard-mounted coffee maker for the

Volkswagen Beetle. The Hertella

Auto Kaffeemachine was not a success, presumably because even those not

familiar with Sir Isaac Newton's (1642–1727) First Law of Motion (known also as

the Law of Inertia: “An object at rest will remain at rest, and an object in

motion will continue in motion with the same speed and in the same direction

unless acted upon by an unbalanced external force”) could visualise

the odd WCS (worst case scenario).

That it was in 1959 available in 6v & 12v versions is an indication Hertella may have envisaged a wider market because VW didn’t offer a 12v system as an option until 1963 and the company seems to have given some thought to Newtonian physics, the supplied porcelain cups fitted at the base with a disc of magnetic metal which provided some resistance to movement although the liquid obviously moved as the forces were applied. The apparatus was mounted with a detachable bracket, permitting the pot to be removed for cleaning. The quality of the coffee was probably not outstanding because there’s no percolation; the coffee added in a double-layer screen and “brewed” on much the same basis as one would tea-leaves and for those who value quality, a thermos-flask would have been a better choice but there would have been caffeine addicts willing to try the device. The trouble was there clearly weren’t many of them and even in the FRG of the Wirtschaftswunder (the post war “economic miracle”) the fairly high price would have deterred many although now, one in perfect condition (especially if accompanied by the precious documents or packaging) would command a price well over US$1000.

How to advertise a Beetle

Although the popular perception of motoring in the US during the 1960s is it was all about gas-guzzling behemoths and tyre-smoking muscle cars no less thirsty, Detroit’s advertising did not neglect to mention fuel economy and the engineers always had in the range a combination of power-train and gearing options for those for whom that was important; it was a significant if unsexy market. However, the advertising for domestic vehicles, whatever the segment, almost always emphasised virtues like attractiveness and, in the era of annual product updates, made much of things being “new”. Volkswagen took a different approach, centred around the “Think Small” campaign, created by the advertising agency Doyle Dane Bernbach (DDB). Positioning VW Beetle ownership as a kind of inverted snobbery, the campaign embraced simplicity and honesty, quite a contrast with the exaggerations common at the time. The technique was ground-breaking and its influences have been seen in the decades since.

The key theme was one of self-deprecating humor which took the criticisms of the car (quirky, small, ugly, lacking luxuries) and made a headline of them, emphasising instead attributes such as reliability, fuel efficiency, and affordability, all done with some wry observations. Whether making a virtue of the by then dubious qualities of swing axles (centre right) convinced many is uncertain but the "Why are the wheels crooked" one dates from 1962, some three years before the publication of Ralph Nadar's (b 1934) Unsafe at Any Speed (1965) in which a chapter was devoted to the troubling behavior swing axles induced in the Chevrolet Corvair (1960-1969). Still, the focus on authenticity had real appeal in a consumerist age when agencies produced elaborate graphics and full-color photographs taken in exotic locations: VW’s monochromatic look was emblematic of the machine being advertised, one which in 1969 still looked almost identical to one from 1959. A key to the success of the campaign was the template: most of the upper part of the page usually a single image of a Beetle, a caption beneath and then the explanatory text.

The US magazine National Lampoon (1970-1998) ran a parody in the style of VW’s campaign in their Encyclopedia of Humor (1973). The "If Ted Kennedy drove a Volkswagen, he'd be President today" piece not only borrowed the template but also reprised VW’s claim of “watertight construction” which had appeared in one of the manufacturer’s genuine advertisements. Although what the magazine did was protected under the constitution’s first amendment (freedom of speech; freedom of the press) other legal remedies beckoned and Volkswagen filed suit claiming (1) violations of copyright and their trademark and (2) defamation. Apparently, a number of those who had seen the spoof believed it to be real and the company was receiving feedback from the outraged vowing never to buy another VW, a reaction familiar at scale in the age of X (formerly known as Twitter) but which then required writing a letter, putting it in an envelope, affixing a postage stamp and dropping it in the mailbox. So pile-ons happened then but they took longer to form. In a settlement, National Lampoon undertook to (1) withdraw all unsold copies of the 450,000 print run (2) destroy the piece’s hot plate (in pre-digital printing, a physical “plate” was created onto which ink was laid to create the printed copy) and (3) publish in the next issue Volkswagen's explanatory disclaimer of involvement. National Lampoon was also estopped from using the spoof for any subsequent purpose.