Virus (pronounced vahy-ruhs)

(1) An sub- or ultra-microscopic (20 to 300 nm diameter),

metabolically inert, non-cellular infectious agent that replicates only within the cells of

living hosts, mainly bacteria, plants, and animals: composed of an RNA or DNA

core, a protein coat, and, in more complex types, a surrounding envelope. Because viruses are unable to replicate

without a host cell, they are not considered living organisms in conventional

taxonomic systems (though often referred to as live (in the sense of active) when

replicating and causing disease.

(2) A quantity of such infectious agents.

(3) In informal use, metonymically, A disease caused by such an infectious agent; a viral illness.

(4) Venom, as produced by a poisonous animal etc (extinct in this context).

Late 1300s: From the Middle English virus (poisonous substance (this meaning now extinct in this context)), from the Latin vīrus (slime; venom; poisonous liquid; sap of plants; slimy liquid; a potent juice), from rhotacism from the Proto-Italic weisos & wisós (fluidity, slime, poison) probably from the primitive Indo-European root ueis & wisós (fluidity, slime, poison (though it may originally have meant “to melt away, to flow”), used of foul or malodorous fluids, but in some languages limited to the specific sense of "poisonous fluid") which was the source also of the Sanskrit visam (venom, poison) & visah (poisonous), the Avestan vish- (poison), the Latin viscum (sticky substance, birdlime), the Greek ios (poison) & ixos (mistletoe, birdlime), the Old Church Slavonic višnja (cherry), the Old Irish fi (poison) and the Welsh gwy (poison). It was related also to the Old English wāse (marsh). Virus is a noun & a (rare) verb and viral is an adjective; the noun plural is viruses.

The original meaning, "poisonous substance”, emerged in the late fourteenth century and was an inheritance from the Latin virus (poison, sap of plants, slimy liquid, a potent juice) from the Proto-Italic weis-o-(s-) (poison), probably from the primitive Indo-European root ueis-, thought originally to mean "to melt away, to flow" and used of foul or malodorous fluids, but with specialization in some languages to mean "poisonous fluid". It’s the source of the Sanskrit visam (venom, poison) & visah (poisonous), the Avestan vish- (poison), the Latin viscum (sticky substance; birdlime) the Greek ios (poison) & ixos (mistletoe, birdlime), the Old Church Slavonic višnja (cherry). The Old Irish fi (poison) and the Welsh gwy (poison). The meaning "agent that causes infectious disease" emerged in the 1790s, the medical literature of the time describing their manifestation in especially disgusting terms (the word pus most frequent) and one dictionary entry of 1770 contains the memorable: "a kind of watery stinking matter, which issues out of ulcers, being endued with eating and malignant qualities". As early as 1728 (borrowing from the earlier sense of "poison"), it had been used in reference to venereal disease, the first recognizably modern scientific use dating from the 1880s. The first known citation in the context of computing was by Gregory Benford (b 1941) who published The Scarred Man (1970) although it’s often credited to David Gerrold (b 1944), who used the word in this context in When HARLIE Was One (1972).

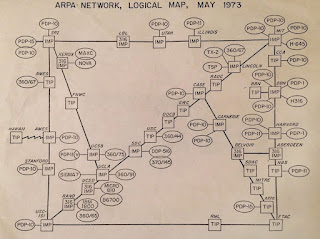

In

computing, theoretical work on the self-replicating code (which is the core of

a digital virus) was published as early as 1971 and what’s regarded as the first

object to behave like a virus (though technically, it would now be called a worm) was released as a harmless amusement on ARPANET

(Advanced Research Projects Agency Network) (ARPANET), the internet’s precursor

network. It was called “creeper, catch

me if you can!" and, perhaps predictably, other nerds rose to the challenge

and release the “reaper” their own worm which killed whatever creepers it found. Creeper & reaper conducted their cat

& mouse game on Digital Equipment Corporation's (DEC) PDP-10, predecessor

to the famous PDP-11 mini-computer and at this point, viruses were genuinely harmless (if time wasting) activities conducted between consenting nerds in the privacy of their parochial networks. However, it was the development of the personal computer (PC) from 1975 and especially the subsequent adoption by business of the IBM-PC-1 (1981) and its clones which created the population in which viruses could spread and while relatively harmless creations like Stoned (1987) tended to amuse because they did little more that display on the screen of an infected device the message "Your PC is now Stoned", there were many others which were quite destructive. The first which came to wide public attention was probably Melissa (1999) which caused much economic loss and the discussion of which (by mostly male writers in the specialist press) excited some criticism from feminists who objected to headlines like "Melissa was really loose, and boy did she get around".

In medicine, the first antivirus was available in 1903, an equivalent (shrink-wrap)

product for computers apparently first offered for sale in 1987 although there

seems no agreement of which of three authors (Paul Mace, Andreas Lüning &

the late John McAfee) reached the market first.

The adjective viral (of the nature of, or caused by, a virus) dates from

1944 as applied in medicine whereas the now equally familiar, post

world-wide-web sense of stuff "become suddenly popular through internet

sharing" is attested by 1999 although most seem convinced it must have

been in use prior to this.

The rhinovirus (one of a group of viruses that

includes those which cause many common colds) was first described in 1961, the

construct being rhino- (from the Ancient Greek rhino (a combining form of rhis (nose) of uncertain origin) + virus. The noun virology appeared in 1935 to describe

the then novel branch of science and parvovirus (a very small virus), the

construct being parvi- (small, little)

+ the connecting element -o- + virus was coined in 1965 to describe the decreasingly

small objects becoming visible as optical technology improved. The rotavirus (a wheel-shaped virus causing

inflammation of the lining of the intestines), the construct being rota (wheel)

+ virus dates from 1974.

The adjective virulent dates from circa 1400 in reference to wounds, ulcers etc (full of corrupt or poisonous matter), from the Latin virulentus (poisonous), from virus; the figurative sense of "violent, spiteful" attested from circa 1600; virulently the related form. The mysterious reovirus was a noun coined in 1959 by Polish-American medical researcher Dr Albert Sabin (1906-1993), the “reo-“ and acronym for “respiratory enteric orphan”, to describe viruses considered orphans in the sense of not being connected to any of the diseases with which they were associated. More technical still was the (1977) retrovirus, an evolution of the (1974) retravirus (from re(verse) tra(nscriptase) + connective -o- + virus), explained by it containing reverse transcriptase, an enzyme which uses RNA instead of DNA to encode genetic information, thus reversing the usual pattern. While these things are usually the work of committees, there seems to be nothing in the public record to suggest why “retro-“ was preferred to “retra-“, the assumption being “retro-“ more explicitly indicated "backwards."

During the initial 2019 outbreak in Wuhan of what

is now called COVID-19, both virus and disease were mostly referred to as

"coronavirus", "Wuhan coronavirus" or "Wuhan

pneumonia". There had been a long

tradition of naming diseases after the geographical location where they were

first reported (Hong Kong flu, Spanish flu etc) but this could be misleading. The Spanish flu, associated with the pandemic

of 1918-1920, was actually first detected elsewhere, either on the World War I battlefields

of France or (more probably) a military camp in the United States but, because Spain was a

neutral in the conflict, there was no military censorship to limit reporting so

warnings about this especially virulent influenza were printed in the Spanish

press. From here, it was eventually

picked up and publicized as “Spanish flu” although, doctors there, in an early

example of contract tracing, were aware of vectors of transmission and insisted

it was the “French flu” because this was where their back-tracing led. This had no

effect beyond Spain and it’s ever since been known as “Spanish flu” although the practice of using geographical references has now been abandoned, a linguistic sanitization which has extended to anything likely to cause offence, the recently topical Monkeypox now called Mpox which seems hardly imaginative.

Representation of a coronavirus.

In January 2020, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) recommended the name 2019-nCoV & 2019-nCoV acute respiratory disease as interim names for virus and disease respectively (although “human coronavirus 2019”, “HCoV-19” & “hCoV-19” also exist in the record). The committee’s recommendation conformed to the conventions adopted after it was decided in 2015, to avoid social stigma, to cease the use of geographical locations or identities associated with specific people(s) in disease-related names. Although well understood by scientists, the WHO must have thought them a bit much for general use and in February 2020, issued SARS-CoV-2 & COVID-19 as the official nomenclature: CO=corona, VI=virus, D=disease & 19=2019 although for a while, confusingly, documents issued by the WHO sometimes referenced “COVID-19 virus” rather than the correct SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; the name adopted because of the close genetic relationship to the first SARS outbreak in 2003 (now retrospectively listed as SARS-Cov-1).

One of civilizations modern quests is the hunt for the “viral video” (video content posted to the internet which rapidly and at scale is passed from user to user in a pattern analogous to the spread of a virus). A viral video can bring one (at least a transitory fifteen minutes) fame, cash and perhaps a spike in the traffic to one’s OnlyFans page but, depending on the content and context, what can also ensue is infamy, cancellation or incarceration so, as the Justine Sacco (b 1985) “incident” illustrates, caution should be a prelude to posting. A minor industry has sprung up to advise all who aspire to be content providers and one popular theme is what makes a clip go viral. On the basis of posted advice, it seems clear there’s no one set of parameters which need be used but there’s certainly a collections of characteristics which encourage sharing and while virality remains unpredictable, most clips which spike do share common traits although with some obvious exceptions, the phenomenon tends to be siloed, a clip which wildly goes vial among one market segment can be almost un-shared within another. The markers likely to trigger a viral reaction have been categorized thus:

(1) Original content: This need not of necessity be something novel or in any way unique but both those qualities can be valuable, something genuinely new most likely to grab attention.

(2) Creativity: This can mean something unconventional in approach or the use of existing techniques with high production values.

(3) Emotional Resonance: Known also as “emotional manipulation”, content which can evoke feelings of joy, awe surprise, sadness, rage, disgust etc are more likely to be shared.

(4) Brevity: Most viral are videos which are short (less than two minutes is typical) and to some extent this is technologically deterministic, so much viral media coming from sites which curate such material and this has encouraged a ecosystem of what are now called “viral sites” (BuzzFeed, Upworthy, Distractify, LittleThings, Thought Catalog, UPROXX, Vox, Daily Dot, Ranker, Words etc). Students of cause & effect can ponder the interplay between the emergence of these platforms and the alleged shortening of the planet’s collective attention span.

(5) The hook: Two minutes is a long time in the context of scrolling and while it’s not impossible for a clip where the “best big” comes at the end to go viral, it is less likely because not enough viewers will have persisted for it to gain critical mass (hence the oft-seen plaintive plea "watch to the end!"). Ideally, interest to the point of being committed to watch to the end should be captured in the first few seconds. If the material is in the form of music, it should appeal (in a TikTok sort of way) with the sort of formula the pop music generators perfected in decades past.

(6) Entertaining: Clips go viral for all sorts of reasons but nothing seems to work better that something which makes people laugh; it’s more popular even than outrage, the internet’s other way of life.

(7) Relatability: Relatability (that with which people can identify) is a concept which can be vertical (something with great appeal to certain section of the population) or horizontal (something with general appeal to many sections of the population). Content with a universal appeal (cross-cultural relevance) should in theory produce the greatest numbers but something aimed specifically at one market can produce greater tangible results (revenue).

(8) A twist: The ultimate viral video content is probably something with a hook at the start which grabs the attention, maintains a commitment to watching and then concludes with a dramatic, unexpected or funny ending.

(9) Ease of sharing: When file formats were not (more or less) standardized and cross-platform compatibility couldn’t be assumed, this was something to consider but now most content is optimized for the majors (TikTok, Instagram, YouTube etc), the process close to effortless.

(10) A Call-to-Action: This means something which encourages sharing and that can be explicit (“please share”) or a subliminal message which induces in viewers either a desire to share or a feeling they are somehow obliged to share. Those which are controversial (the more polarizing the better) and which enable users to engage in “virtue signalling” (sharing a clip as a display of moral superiority) should produce more reaction.

(11) Relevance: If it’s funny enough nothing else really matters but something tied to the zeitgeist tends most quickly to gain traction. These can be tied to trending hashtags or challenges on social media and are the most obvious form of encouraging interaction without demanding any real commitment.

(12) Celebrity association. This need not be an endorsement (there evidence there’s now much cynicism about this) but if a celebrity shares something, it should be an accelerant in the process.

A classic viral clip: Man in Finance mixed by DJs Billen Ted & David Guetta, written and sung by Megan Boni (Girl on Couch).

I'm looking for a man

in finance

Trust fund

Six-five (ie 6 foot,

five inches tall)

Blue eyes

That's all I want

The lyrics

to the track Man in Finance (sometimes

as Looking for a Man in Finance) were

written by Megan Boni (b 1997 and now better known as @girl_on_couch). In April 2024 Ms Boni uploaded the clip (as a

cappella piece) to TikTok and she says it was a parody of the unrealistic

expectations of men held by young single women such as herself. Attached to the original (a viral-friendly 19

seconds in duration) upload, Ms Boni requested DJs in her audience to “…make this into

an actual song plz just for funzies.” The DJs responded, the edited clip went viral

and Ms Boni quit her “9 to 5” to enter the music industry.

Catchy though it was, dropping the tune was not without risk because the internet is riddled with those combing sites to find some way of being offended (or disrespected, marginalized etc) and in an interview with the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) she did note one comment on her post was that wanting a man with “blue eyes” meant she must be “racist” but there was little support for that and she escaped cancellation. Still, the risks were clearly there because each line was laden with offence for the hordes anxious to be outraged:

I'm looking for a man in finance (critique: supports a system which is exploitative and exists to alienate to people from the fruits of their labor by appropriating the surplus value).

Trust fund (critique: materialist)

Six-five (critique: heightist and thus exclusionary)

Blue eyes (critique: racist and thus exclusionary)

That's all I want (there will be those who think this objectionable)

Really, people should just enjoy the beat. As a parody it works well, a young spinster lamenting her status as a singleton by restricting the acceptable catchment of who might seek courtship to (1) “a man” (thereby excluding half the population), (2) employed in the “finance” industry (a tiny fraction of the male population), (3) the beneficiary of a “trust fund” (a tiny fraction of men working in the finance industry) (4) “six-five” tall (a tiny fraction of men working in the finance industry who are the beneficiaries of a trust fund) and (5) has “blue eyes” (an unknown but small percentage of 6’ 5" (1.95 m) tall men who are the beneficiaries of a trust fund and employed in the finance industry). That math is of course what makes the last line (That’s all I want) so funny. Ms Boni should maintain her high standards because she deserves to find the man of her dreams.

%20assembly%20and%20egress.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment