Basketweave (pronounced bah-skit-weev

(U) or bas-kit-weev (non-U))

(1) A plain woven pattern with two or more groups of warp

and weft threads are interlaced to render a checkerboard appearance resembling

that of a woven basket; historically applied especially (in garment &

fabric production) to wool & linen items and (in furniture, flooring etc), fibres

such as cane, bamboo etc.

(2) Any constructed item assembled in this pattern.

(4) In the natural environment, any structure (animal,

vegetable or mineral) in this pattern.

(5) In automotive use, a stylized wheel, constructed usually

in an alloy predominately of aluminum and designed loosely in emulation of the

older spoked (wire) wheels.

1920–1925: The construct was basket + weave (and used variously

as basketweave, basket-weave & basket weave depending on industry, product,

material etc). Basket was from the thirteenth

century Middle English basket (vessel

made of thin strips of wood, or other flexible materials, interwoven in a great

variety of forms, and used for many purposes), from the Anglo-Norman bascat, of obscure origin. Bascat

has attracted much interest from etymologists but despite generations of

research, its source has remained elusive.

One theory is it’s from the Late Latin bascauda (kettle, table-vessel), from the Proto-Brythonic (in

Breton baskodenn), from the Proto-Celtic

baskis (bundle, load), from the

primitive Indo-European bhask- (bundle) and presumably related to the Latin fascis (bundle, faggot, package, load) and a doublet of fasces. In ancient Rome, the

bundle was a material symbol of a Roman magistrate's full civil and military

power, known as imperium and it was adopted

as the symbol of National Fascist Party in Italy; it’s thus the source of the

term “fascism”. Not all are convinced, the

authoritative Oxford English Dictionary (OED) noting there is no evidence of

such a word in Celtic unless later words in Irish and Welsh (sometimes counted

as borrowings from English) are original.

However, if the theory is accepted, the implication is the original

meaning was something like “wicker basket”, wicker one of the oldest known

methods of construction. The word was

first used to mean “a goal in the game of basketball” in 1892, the use extended

to “a score in basketball” by 1898. In

the 1980s, as operating systems evolved, programmers would have had the choice

of “basket” or “bucket” to describe the concept of a “place where files are stored

or reference prior to processing” and they choose the latter, thus creating the

“download bucket”, “handler bucket” etc.

On what basis the choice was made isn’t known but it may be that baskets,

being often woven, are prone to leak while non-porous buckets are not. Programmers hate leaks. Basketweave, basketweaver & basketweaving are nouns; the noun plural is basketweaves. The adjectives basketweavelike, basketweaveish & basketweavesque and the verbs basketweaving and basketweaved (the verbs of politicians being evasive) are all non-standard.

A classic basketweave pattern.

Weave was from the Middle English weven (to weave), from the Old English wefan (to weave), from the Proto-West Germanic weban, from the Proto-Germanic webaną,

from the primitive Indo-European webh

(to weave, braid).

The sense of weave as “to wander around; not travel in a straight line”

was also in the early fourteenth century absorbed by the Middle English weven and was probably from the Old Norse veifa (move around, wave), related to the Latin vibrare, from vibrō (to vibrate, to rattle, to twang; to deliver or deal (a

blow)), from the Proto-Italic wibrāō, denominative of wibros, from the primitive Indo-European

weyp- (to oscillate, swing) or weyb-.

The root-final consonant has never been clear and reflexes of both are

found across Indo-European languages.

The verb sense of “something woven” dates from the 1580s while the meaning

“method or pattern of weaving” was from 1888.

The notion of “to move from one place to another” has been traced to the

twelfth century and was presumably derived from the movements involved in the

act of weaving and while it’s uncertain quite how the meaning evolved, it’s

documented from early fourteenth century as conveying “move to and fro” and in

the 1590s as “move side to side”, In pugilism

it would have been a natural technique from the moment the first punch was

thrown but formally it entered the language of boxing (as “duck & weave”)

in 1918, often as weaved or weaving. By

analogy, the phrase “duck & weave” came to be used of politicians attempting

to avoid answering questions (crooked Hillary Clinton (b 1947; US secretary of state 2009-2013 an exemplar case-study). In the

military, weave was also used to describe evasive maneuvers undertaken on land

or in the air but not at sea, the Admiralty preferring zig-zag, as the pattern

would appear on charts. The fencing method known as teenage (and as the New Yorker insists, not "teen-age") is a kind of basketweave. Basketweave is a

noun & adjective and (in irregular use) a verb and basketweaver is a noun;

the noun plural is basketweaves.

Attentive basketweavers: Students in a lecture (B.A. (Peace Studies)) at Whitworth University, Spokane, Washington, USA.

A basketweaver is of course “one who weaves baskets” but in

idiomatic use, basketweaver is used also to mean “one whose skills have been

rendered redundant by automation or other changes in technology”. The term “underwater basketweaving” is used

of university course thought useless (in the sense of not being directly

applicable to anything vocational) and is applied especially to the “studies”

genre (gender studies, peace studies, women’s studies etc). Beyond education, it can be used of anything

thought “lame, pointless, useless, worthless, a waste of time etc”. Basketweaving is also a descriptor of a long

and interlinked narrative of lies, distinguished from an ad-hoc lie in that in

a basketweave of lies, there are dependencies between the untruths and, done

with sufficient care, each can act to reinforce another, enabling an entire

persona to be constructed. It’s the most

elaborate version of a “basket of lies” and can work but, like a woven basket, if

one strand becomes lose and separates from the structure, under stress, the

entire basket can unravel, spilling asunder the contents.

Highly

qualified content provider Busty Buffy (b 1996) perched on basketweave chair.

The term “basketweave

chair” (or other furniture types) refers not to a certain material or fabric

used in the construction but instead describes the woven or interlaced design, most

often using wicker, rattan or synthetic fibres, creating a “basket-like” pattern

on the seat, sides or back. Widely used

(and long a favourite in the tropics or other hot places because the open-construction

aided cooling by permitting air-flow), the designs range from purely decorative

accent pieces to functional furniture.

However, because specific load-bearing capacity of basketweaves tended (for

a given surface area) to be less than more solid implementations of the same

shape, basketweaves often were used as decorative side-panels which were not

subject to stress and this was a notable motif in the art deco era. Whatever the material, the defining

characteristic was the interlaced or woven pattern and the choice of material

tended to be dictated by (1) price, (2) regional availability, (3) strength

required and (4) desired appearance. Rattan

was known for its strength & flexibility but the term “wicker” (a general

term for woven plant stems) was often used interchangeably (and sometimes misleadingly)

while synthetic wickers entered mass-production in the 1950s, offering durability

and increased weather-resistance but, although mimicking the look of natural fibres,

remained (on close examination), obviously “a plastic” One trend for outdoor furniture has been to

use strands of aluminium, a strong, lightweight metal which doesn’t rust but

can be subject to corrosion.

1960

Rolls-Royce Phantom V Sedanca de Ville by James Young (the quad headlights presumably a later addition because they didn't appear on the Phantom V until 1963, left), 1930s art deco lounge chair with rattan side panels (centre), 1965 Rolls-Royce Phantom V Seven

Passenger Limousine with Sedanca de Ville coachwork by James Young (right). In the US, the Sedanca de Ville style (the driver's compartment open to the elements while that for the passengers was enclosed) was often referred to as "Town Car", a direct borrowing from the use with horse-drawn carriages.

Wicker was a common sight

on early automobiles because the rearward protrusion which evolved ultimately

to become the “trunk” (dubbed “boot” by the English (and thus the use in most

of the old British Empire) because of a different tradition) began life as

literally a luggage trunk (often of wicker) which was strapped or in some way secured

to the vehicle’s back. This was an

unmodified adaptation of the practice from the days of horse-drawn carriages

when trunks would be carried on the back, on the roof or wherever they could be

made to fit. That was pure functionalism

but cane-work had often been used as a decorative element on coaches, especially

the ones commissioned by the rich for their personal use and these owners were

sometimes nostalgic, thus for years the frequent appearance of cane basketweave

(both real and painted) patterned panels on the sides of cars. As the older generation died off, the trend

faded but during the inter-war years it lingered, becoming one of those markers

of exclusivity, transmitting to all and sundry one had something bespoke and

there were coach-builders still adding the stuff as late as the 1960s, a last

link with the old horse-drawn broughams. It was expensive and therefore rare (anattraction for the tiny number of customers) because the process used a

specially thickened paint which was hand-applied in a very narrow crosshatch

pattern on a body panel laid flat.

Essentially, a coach-builder’s version of hand-stitched lace, it was a tedious,

labor-intensive activity able to be accomplished only by a handful of

increasingly aged craftsmen, demand so low in the post-war years there was

little incentive to train young replacements.

It’s now often called “hand-painted faux cane-work” but James Young

listed the option as “decorative sham cane”. Now of course the look immaculately could be

emulated with the use of 3D printing but it’s doubtful there'll be much demand.

Official portrait of Representative the honorable George Santos.

A

classic basketweaver is George Anthony Devolder Santos (b 1988) who, in the

2022 mid-term elections for the US Congress, was elected as a representative (Republican) for New York's 3rd congressional district.

Although he seems to have passed untroubled through the Republican Party’s

candidate vetting process, after his election a number of media outlets

investigated and found his public persona was almost wholly untrue and

contained many dubious or blatantly false claims about, inter-alia, his mother, personal biography, education, criminal record,

work history, financial status, ancestry, ethnicity, sexual orientation & religion. When confronted, Mr Santos did admit to lying

about certain matters, was vague about some and ducked and weaved to avoid

discussing others, especially the fraud charges in Brazil he avoided by fleeing

the country. Although a life-long Roman

Catholic, Mr Santos on a number of occasions claimed to be Jewish, even fabricating

stories about his family suffering losses during the Holocaust. Later, after the lies were exposed, he told a

newspaper “I never claimed to be Jewish. I am Catholic. Because I learned my maternal

family had a Jewish background I said I was ‘Jew-ish.” In the right circumstances, delivered on-stage

by a Jewish comedian, it might have been a good punch-line.

Few are laughing however and Mr Santos is under investigation

by both Brazilian and US authorities.

However, despite many calls (from Republicans and Democrats alike) that

he resign from Congress, Mr Santos has refused and the Republican house

leadership, working with an unexpectedly paper-thin majority, has shown no enthusiasm

to pursue the matter. What Mr Santos has

done is expose the limitations of the basketweaving technique. While a carefully built construct can work,

it relies on no loose threads being exposed and while this can be manageable

for those not public figures, for anyone exposed to investigation, in the

twenty-first century such deceptions are probably close to impossible to

achieve and Mr Santos was probably lured into excessive self-confidence

because, in relative anonymity, he had for years managed to deceive, fooling many

including the Republican Party and perhaps even himself. In retrospect, he might one day ponder how he

ever thought he’d get away with it. One

thing that remains unclear is how he should be addressed. Members of the House of Representatives typically

are addressed as "the honorable" in formal use but this is merely a courtesy

title and is not a requirement. The use

is left to individual members and as far as is known, Mr Santos has not yet

indicated whether he wishes people to address him as “the honorable George Santos”.

Of wheels

Borrani wire wheels on 1972 Ferrari 365 GTB/4 (Daytona)

coupé (far left), ROH “Hotwire” wheels on 1974 Holden Torana SL/R 5000 (with after-market flares emulating those used on the L34 (1974) and A9X models (1977-1978)), centre left), “Basketweave”

wheels on 1990 Jaguar XJS coupé (centre right) & 1986 Holden Piazza (a badge-engineered Isuzu Piazza (1981-1993) which failed to find success in Australia because the on-road dynamics didn't match the high price and attractive lines).

Basketweave wheels remain popular (although some feelings

may become strained when it comes time to clean the things) but visually, the use of “basketweave”

to describe the construction was sometimes a bit of a stretch and often “lattice” was is preferred which seems architecturally closer. Were

the motif of the classic basketweave to be applied to a wheel it would look

something those used on the Holden Piazza, briefly (1986-1989) available on the

Australian market. Because it’s not easy

successfully to integrate something inherently square or rectangular into a

small, circular object, such designs never caught on although variations were

tried. The “basketweave” wheels which

did endure owed little to the classic patterns used in fashion, furniture & architecture although there are

identifiable hints in the construction so people understand the connection and

rather than thought of as a continuation of the design elements drawn from the traditions

of weaving, the wheels really established a fork of the meaning. As a design, they were an evolution of the “hotwire”

style popular in the 1970s when was a deliberate attempt to echo the style of

the classic spoked (wire) wheels which, being lighter and offering better brake

cooling properties than steel disk wheels, were for decades the wheel of choice

for high performance vehicles. That

changed in the 1960s as speeds & vehicle weight rose and tyres became wider

and stickier, a combination of factors which meant wire wheels were no longer

strong enough to endure the rising stresses.

Additionally, the wire wheel was labor intensive to make in an era when

that beginning to matter, wheels cast from an alloy predominately of aluminum

were cheaper to produce as well as stronger.

Pink & polka-dot combo by by Amiparism: Lindsay Lohan, in Ami three button jacket and flare-fit trousers in wool gabardine with Ami small Deja-Vu bag, Interview Magazine, November 2022. Jaguar first fitted the basketweave (or lattice and some Jaguar owners call them "starflake") wheels in 1984.

The car is a Jaguar XJS (1975-1996 and labeled XJ-S until mid-1991) convertible. Upon debut, the XJ-S was much criticized by those who regarded as a "replacement" for the slinky E-Type (although, belying appearances, the XJ-S was more aerodynamically efficient), but Jaguar had never thought of it like that, taking the view motoring conditions and the legislative environment had since 1961 changed so much the days of the classic roadsters were probably done except for a few low volume specialists. In truth, in its final years, the E-Type was no longer quite the sensuous shape which had wowed the crowed at the 1961 Geneva Salon but most critics though it still a more accomplished design. In the West, the 1970s were anyway a troubled and the XJ-S's notoriously thirsty 5.3 litre (326 cubic inch) V12 wasn't fashionable, especially after the second oil shock in 1979 and the factory for some months in 1981 ceased production, a stay of execution granted only when tests confirmed the re-designed cylinder head (with "swirl combustion chambers") delivered radically lower fuel consumption. That, some attention to build quality (which would remain a work-in-progress for the rest of the model's life) and improving economies of both sides of the Atlantic meant the machine survived (indeed often flourished) for a remarkable 21 years, the last not leaving the factory until 1996.

Jaguar didn't offer full convertible coachwork until 1988 but under contract, between 1986-1988, Ohio-based coachbuilders Hess & Eisenhardt converted some 2000 coupés. Unlike many out-sourced conversions, the Hess & Eisenhardt cars were in some ways more accomplished than the factory's own effort, the top folding completely into the body structure (al la the Mercedes-Benz R107 (1971-1989) or the Triumph Stag (1969-1977)). However, to achieve that, the single fuel tank had to replaced by a pair, this necessitating duplicated plumbing and pumps, something which proved occasionally troublesome; there were reports of fires but whether these are an internet myth isn't clear and tale Jaguar arranged buy-backs so they might be consigned to the crusher is fake news. The one with which Ms Lohan was photographed in Miami was manufactured by Jaguar, identifiable by the ,ore visible bulk of the soft-top's folding apparatus.

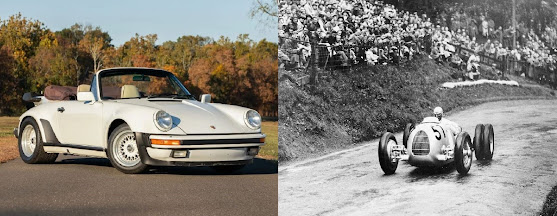

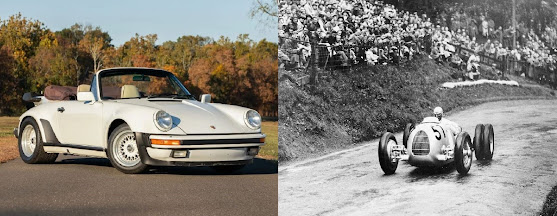

Variations on a theme: 1988

Porsche 911 (930 with 3.3 litre Flat-6) Turbo Cabriolet (left) and Hans Stuck (1900–1978) in Auto

Union Type C (6.0 litre V16), Shelsley Walsh hill climb, Worcestershire,

England, June 1936 (right).

The Porsche

is fitted with three-piece, 15 inch BBS RS basketweave wheels with satin lips: The

rear units are 11 inches in width (running 345/35 tyres) while at the front the

wheels are 9 inches wide (mounted with 225/50 tyres). Although advances in electronics have since the early 1990s made the behaviour of the most powerful rear-engined Porsches easier to

tame, in 1988, the best way to ameliorate the inherent idiosyncrasies of the

configuration was to fit wider wheels, increasing the rubber’s contact area with

the road. The idea was not new, both

the straight-eight Mercedes-Benz W125 and the V16 Type C Auto-Union Grand Prix

cars of 1937 using twin rear tyres when run in hill climbs. The Porsche 930 (1975-1989) quickly gained

the nickname “widow maker” but the Auto Union, which combined 520 horsepower

and a notable rearward weight bias with tyres narrower than are these days used

on delivery vans, deserved the moniker more.

Fitting the second set of rear wheels did help but the handling characteristics

could never be made wholly benign and it wasn’t until the late 1950s that

mid-engined Grand Prix cars became manageable and notably, they had about half

the power of the German machines of the 1930s.